The Shuttle-Mir Program, the first major cooperative human space flight endeavor between the United States and Russia since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project of the mid-1970s, grew out of bilateral government agreements signed in 1992. The collaboration provided much needed experience for both sides in working together, particularly important once Russia was brought aboard as a partner in the International Space Station (ISS) Program in 1993. As the Shuttle-Mir Program was initially envisioned, a Russian cosmonaut would make a short-duration flight aboard a US Space Shuttle mission, an American astronaut would make a long-duration flight aboard the Russian Mir space station, and a Space Shuttle would dock with Mir to return the astronaut to Earth. Central to this effort was the conduct of life sciences experiments while the astronaut was aboard Mir, providing NASA with the first long-duration medical experience since Skylab in the early 1970s. To support this effort, NASA deployed 2,000 pounds of research hardware to Mir, the first items launched aboard Progress resupply vehicles but the majority installed aboard Spektr, a science module that had been awaiting launch to expand Mir’s capabilities. When the Shuttle-Mir Program later expanded to include additional astronaut flights to Mir, NASA also outfitted the Priroda module with research hardware.

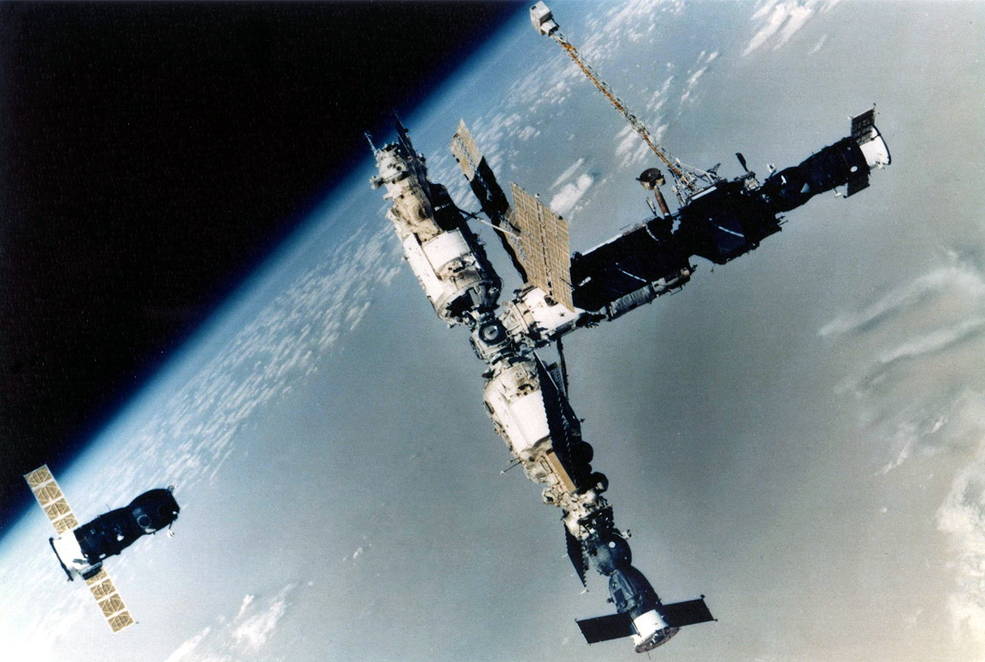

Left: Official patch of the Shuttle Mir Program. Right: Mir space station as it appeared in 1994 photographed by cosmonauts aboard a station-keeping Soyuz spacecraft – Base Block, Kvant 1 and a docked Progress cargo vehicle are at upper right, Kvant 2 is the module facing upward, Kristall with a docked Soyuz facing downward, and a Progress approaches from the left.

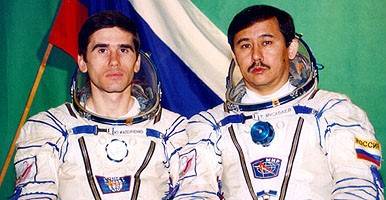

The first element of the Mir space station, the Base Block, was launched in 1986. By the summer of 1994, Mir had been augmented with three additional modules – Kvant 1, Kvant 2, and Kristall. The station had already hosted 15 long-duration expeditions when the Expedition 16 crew of Yuri I. Malenchenko and Talgat A. Musbayev launched on July 1 from the Baykonur Cosmodrome. They docked with Mir two days later and joined Expedition 15 cosmonauts Viktor M. Afanasyev, Yuri V. Usachyov, and Valeri V. Polyakov aboard. Afansayev and Usachyov returned to Earth on July 9, but Polyakov, a medical doctor, remained on board with Malenchenko and Musabayev. He would go on to set a single-flight duration record of 438 days that stands to this day, returning to Earth in March 1995.

Left: Mir Expedition 16 crewmembers Malenchenko (left) and Musabayev. Right: Mir Expedition 16 mission patch.

As noted above, one of the goals of the Shuttle-Mir Program was for the two space-faring nations to learn to work together, not only at a programmatic level but also at an engineering level. The latter included learning how to install and operate NASA hardware in Russian vehicles, both for launch and on-orbit operations. Bilateral agreements were negotiated on the testing required to certify NASA hardware to operate in Russian spacecraft and on any interface hardware that may be required. Due to the short schedules available to make hardware ready to fly to Mir, existing Shuttle-based experiments were appropriately modified.

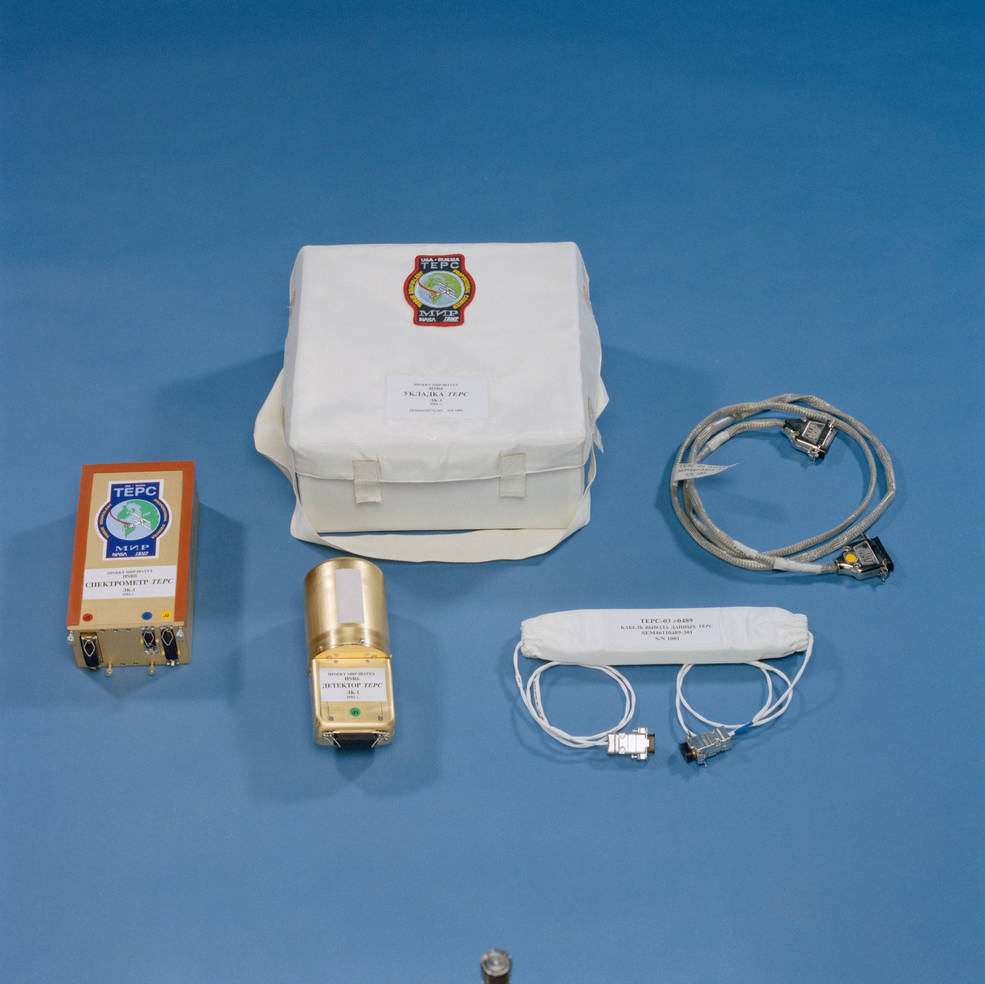

The three pieces of equipment that launched aboard Progress M-24 – (left to right) SAMS, MIPS-1, and TEPC.

Three pieces of research hardware were designated to launch aboard Progress M-24 in August 1994, the first cargo vehicle to launch NASA hardware as part of the Shuttle-Mir Program. The Tissue Equivalent Proportional Counter (TEPC), provided by the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, was a dosimeter to characterize the radiation environment inside the Mir space station. The Space Acceleration Measurement System (SAMS), provided by the Lewis Research Center (LeRC), now the Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, used a system of three Triaxial Sensor Heads (TSH) to characterize the micro-acceleration environment aboard Mir, important to support materials processing and other experiments sensitive to those types of disturbances. And the third item was the JSC-developed Mir Interface to Payloads System-1 (MIPS-1) which was a laptop computer that interfaced directly to Mir’s systems to support telemetry and data downlink for NASA experiments.

Left: SAMS and MIPS-1 undergoing testing in the Mir electrical test facility at RKK Energiya; also present were GRC SAMS engineer Ray Margie (at left) and JSC engineer Trent Mills (third from right). Right: Expedition 16 crewmembers Musabayev (second from left) and Malenchenko (second from right) training with the SAMS and MIPS-1; JSC engineer Mills is at right.

Russian and American engineers completed the required testing of the three experiments in RKK Energiya’s facilities in Moscow in April 1994 and Malenchenko and Musabayev were shown the equipment in a brief training session. The hardware items were packaged into metal cargo boxes and delivered to Baykonur where Russian technicians installed them aboard the cargo vehicle. Progress M-24 launched from Baykonur on Aug. 25, 1994, and began its nominal two-day rendezvous and docking sequence with Mir. However, as it approached Mir’s forward docking port, the docking was called off by the automatic docking system. A second automatic docking attempt on Aug. 30 was also unsuccessful, and Progress actually collided with Mir’s forward docking port and side-swiped a solar array but caused no damage. The third time was the charm, when on Sep. 2 Malenchenko used Mir’s TORU manual docking system to successfully complete the operation.

Left: TEPC hardware packed inside a Progress cargo box. Right: Closed Progress cargo box.

Credits: NASA/Trent Mills.

Left: Workers loading hardware aboard Progress M-24. Middle: The rocket carrying Progress M-24 arrives at the launch pad. Right: Rocket being raised to the vertical position at the launch pad.

Credits: NASA/Gary Kitmacher.

Expedition 16 cosmonauts Malenchenko and Musabayev transferred the TEPC unit from Progress M-24 and initially deployed it in the Kvant-1 module. During later missions, crewmembers relocated it to the Base Block near one of the crew sleep stations, and ultimately TEPC spent time in each of Mir’s modules for a full characterization of the station’s radiation environment. It continued to provide radiation monitoring throughout the Shuttle-Mir Program.

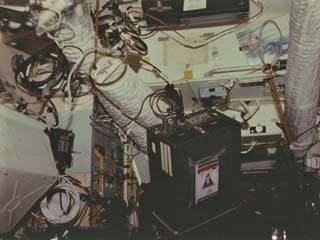

The Expedition 16 crew transferred the SAMS, its three TSHs, and MIPS-1 from Progress M-24 into Mir and activated them on Sep. 28. During this expedition, SAMS data were obtained only in two locations in the Kristall module. The cosmonauts completed seven recording sessions totaling 53 hours before their return to earth on Nov. 4, 1994. They brought back the SAMS data disks from these sessions, which were transported to Moscow and turned over to a NASA representative who delivered them to LeRC on Nov. 21. The SAMS unit remained on orbit until it was returned to Earth during the STS-91 Shuttle mission in June 1998, the longest operating NASA hardware on Mir. During its nearly four years of operations on the Russian space station, it accumulated over 50 gigabytes of data, the equivalent of approximately 75 CD-ROMs. The SAMS Mir unit is on display in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Left: SAMS unit aboard Mir. Right: SAMS on display at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Credits: NASA/Richard DeLombard.

The hardware launched 25 years ago to Mir aboard Progress M-24 represented a modest beginning to an ongoing collaboration between the United States and Russia, first aboard the Mir space station and now aboard ISS. It kicked off a four-year period when thousands of pounds of NASA hardware was integrated into Russian cargo vehicles and Mir modules. Lessons learned about flying NASA hardware on Progress vehicles came in handy after the Columbia accident when we were once again reliant on Russian spacecraft to get science to orbit, this time to ISS. Advanced versions of both SAMS and TEPC currently reside on ISS, providing valuable information to scientists on Earth.