It’s not quite the replicator of Star Trek fame—but it’s seemingly a step in that direction.

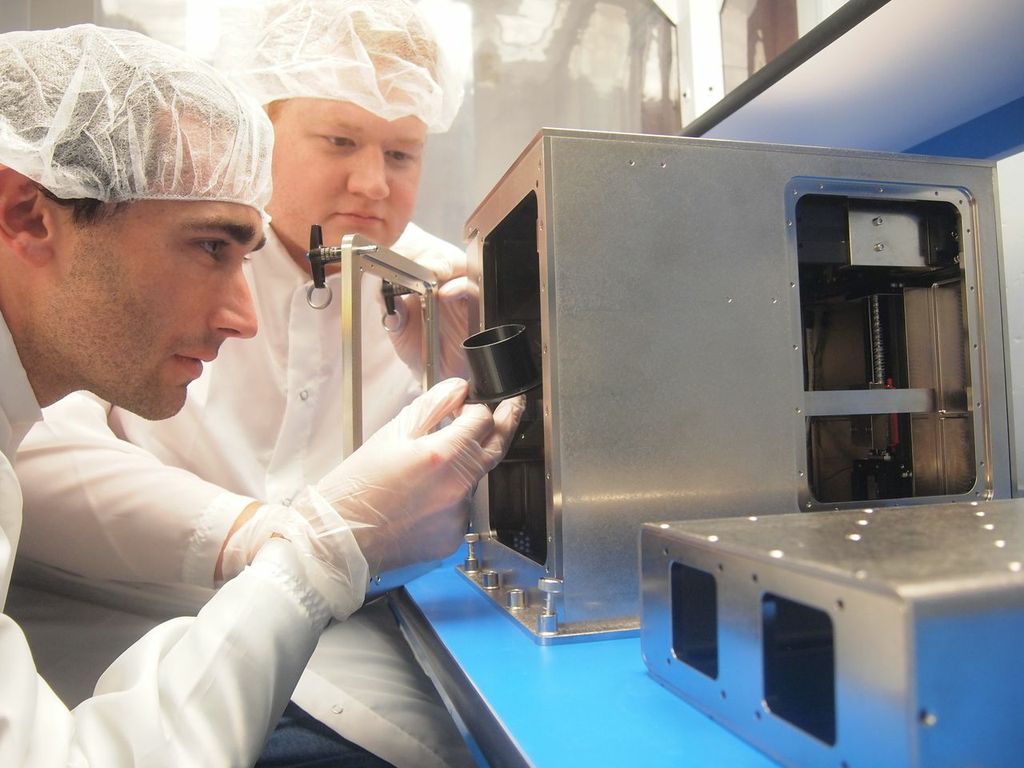

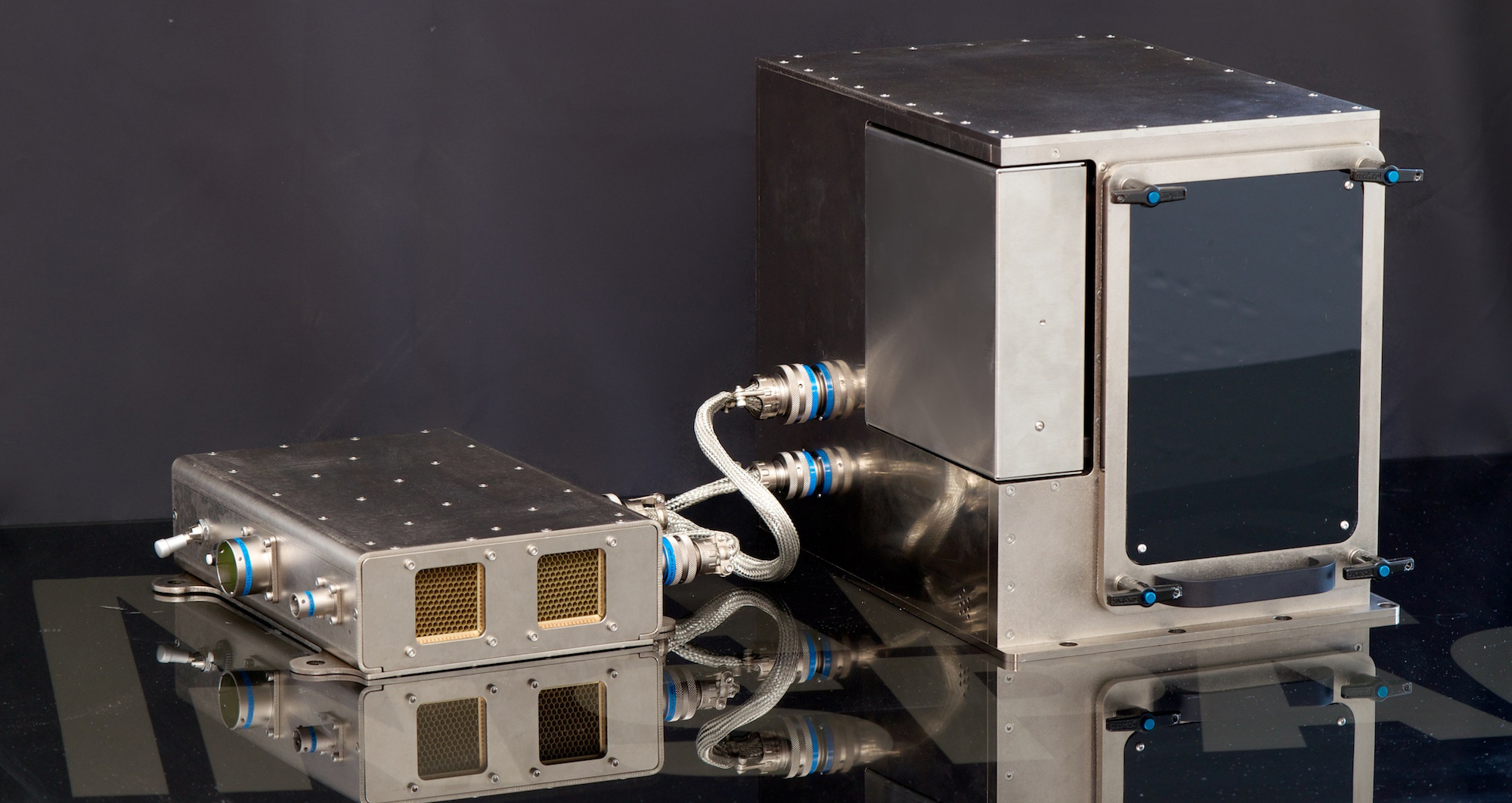

The first 3D printer is soon to fly into Earth orbit, finding a home aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The size of a small microwave, the unit is called Portal. The hardware serves as a ted bed for evaluating how well 3D printing and the microgravity of space combine. Its use in space signals an new era of off-world manufacturing.

The foundation for 3D printing is also known as “additive manufacturing,” which has been evolving for more than three decades. The technology has picked up speed more recently due to new materials and new applications.

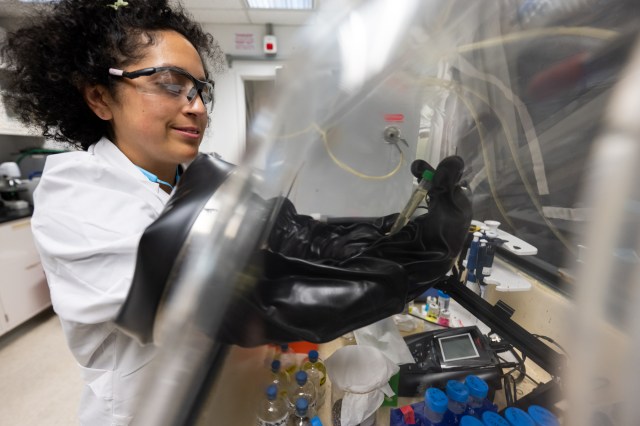

A 3D printer works by extruding heated plastic, and then builds successive layers to make a three-dimensional object. In essence, this test on the ISS might well lead to establishing a “machine shop” in space. The technology demonstration will print objects in the space station’s Microgravity Science Glovebox.

The soon-to-fly 3D printer can churn out plastic objects within a span of 15 minutes to an hour.

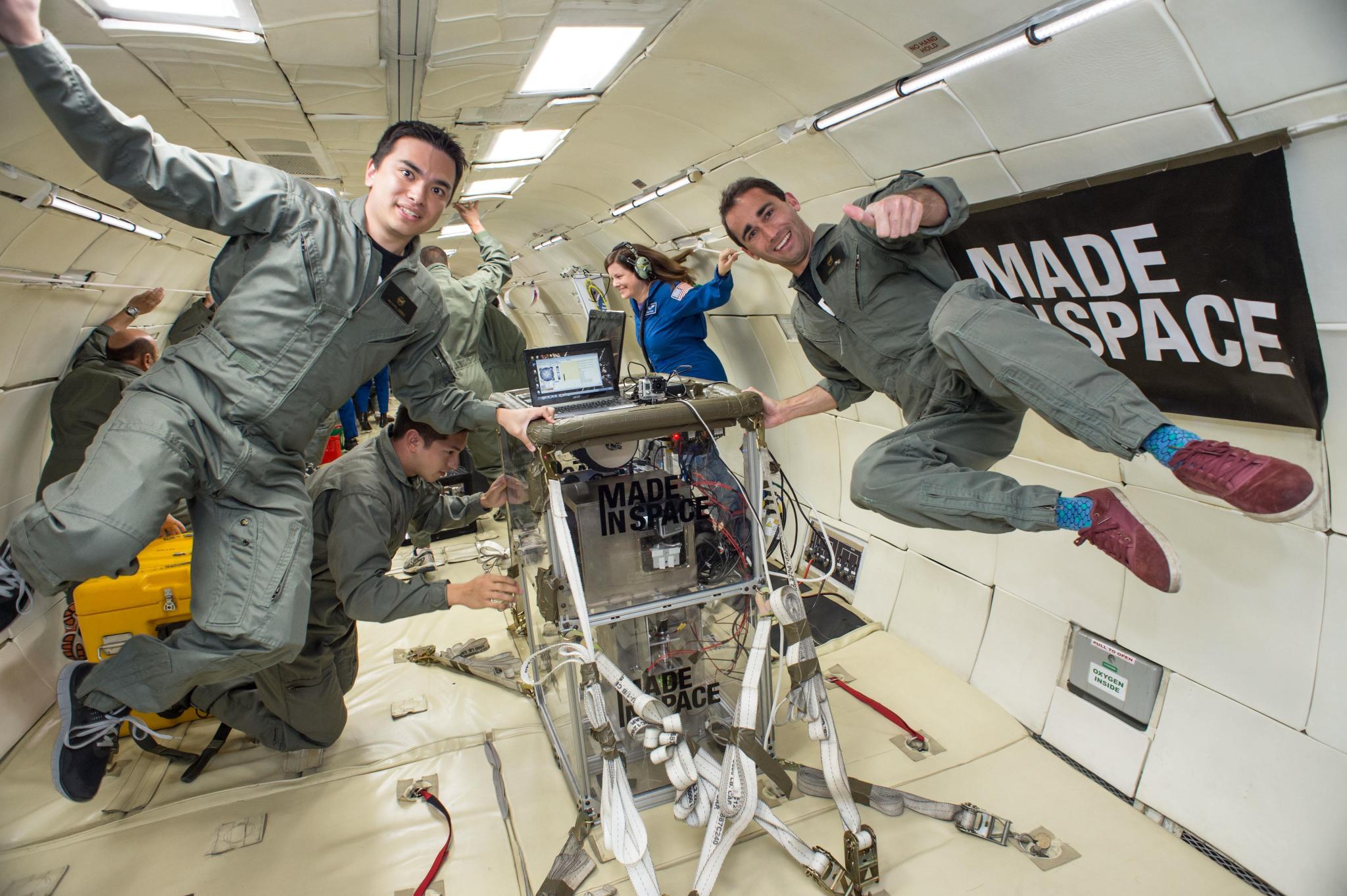

Made In Space

The company behind the Portal 3D printer is Made In Space—a fitting name for this Silicon Valley team comprised of entrepreneurs, space experts and key 3D printing developers. Made In Space is located in the research park at NASA’s Ames Research Center in northern California.

Made In Space was formed in 2010 with the goal of enabling humanity’s future in space, focused on additive manufacturing technology for use in the space environment.

According to the group, manufacturing assets in space, as opposed to launching them from Earth, will accelerate and broaden space development while providing unprecedented access for people on Earth to use in-space capabilities.

Extensive testing

To be lofted into space aboard SpaceX’s next Dragon resupply mission to the ISS, the made-for-space 3D printer is a product of extensive development work.

That effort entailed affiliations between NASA and Made In Space over the years, supported by NASA’s Flight Opportunities Program, research and development contracts under NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program and the space agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

For example, working with NASA, Made In Space chalked up over 30,000 hours of 3D printing technology testing, and 400-plus parabolas of airborne microgravity test flights.

Now the 3D printer is ready for liftoff.

Partners in progress

“It has been a great partnership between Made In Space, our Space Technology Mission Directorate, the Human Exploration and Operations office, and several of our NASA Centers,” said LaNetra Tate, the principal investigator for Advanced Manufacturing at NASA Headquarters.

“Marshall Space Flight Center worked very closely with Made In Space to test out the printer and do side-by-side comparisons with material and processes,” Tate said.

The 3D printer experiment is being done under the tech directorate’s Game Changing Development Program, Tate said, a NASA thrust that seeks to identify and rapidly mature innovative/high impact capabilities and technologies for infusion in a broad array of future NASA missions.

The International Space Station Technology Development Office at the agency’s Johnson Space Center provided the Made In Space team a list of some 20 parts they’d like to be able to manufacture in space. Most of the print designs for those parts have been pre-loaded onto the printer, Tate said. A couple of print designs will be uplinked to the ISS and then printed, she said.

New revolution

“Sometimes I refer to it as a new revolution of additive manufacturing and 3D printing,” Tate said. “People are looking at it as potentially being used for more complex components and primary structures.”

Tate said that 3D printing is experiencing a notoriety that could, eventually, lead to substantial niche areas where it will be most utilized.

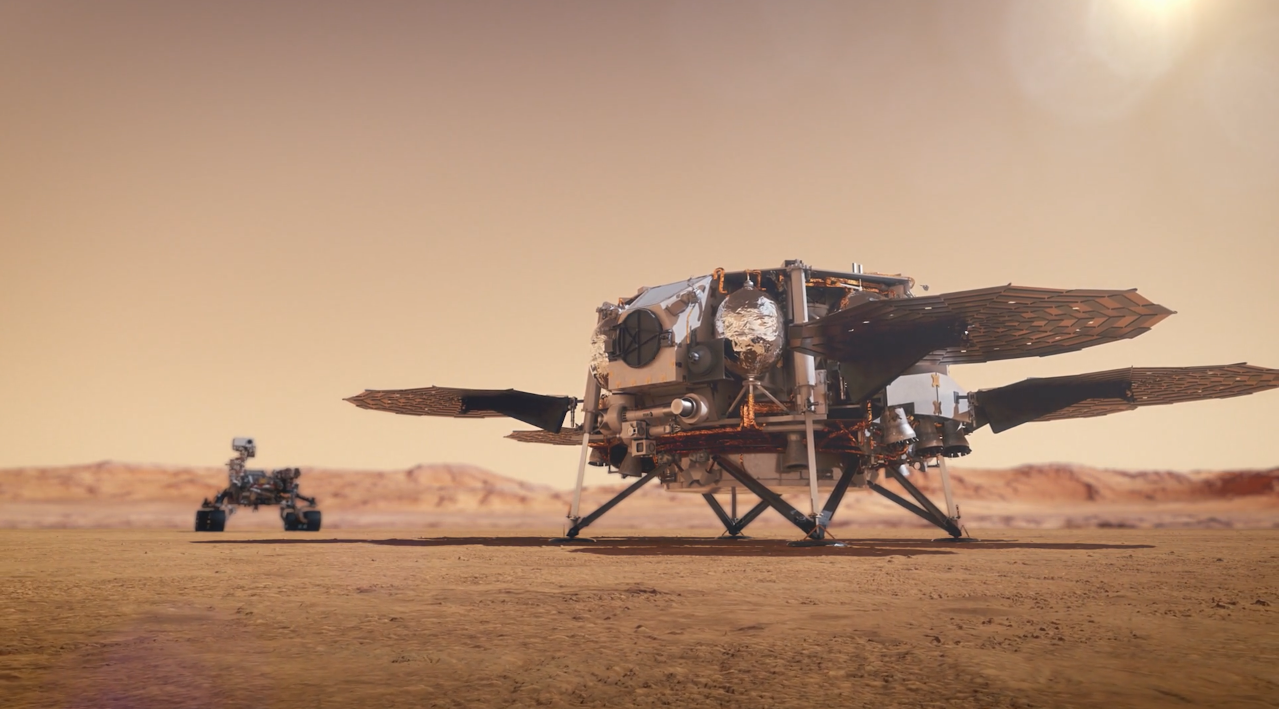

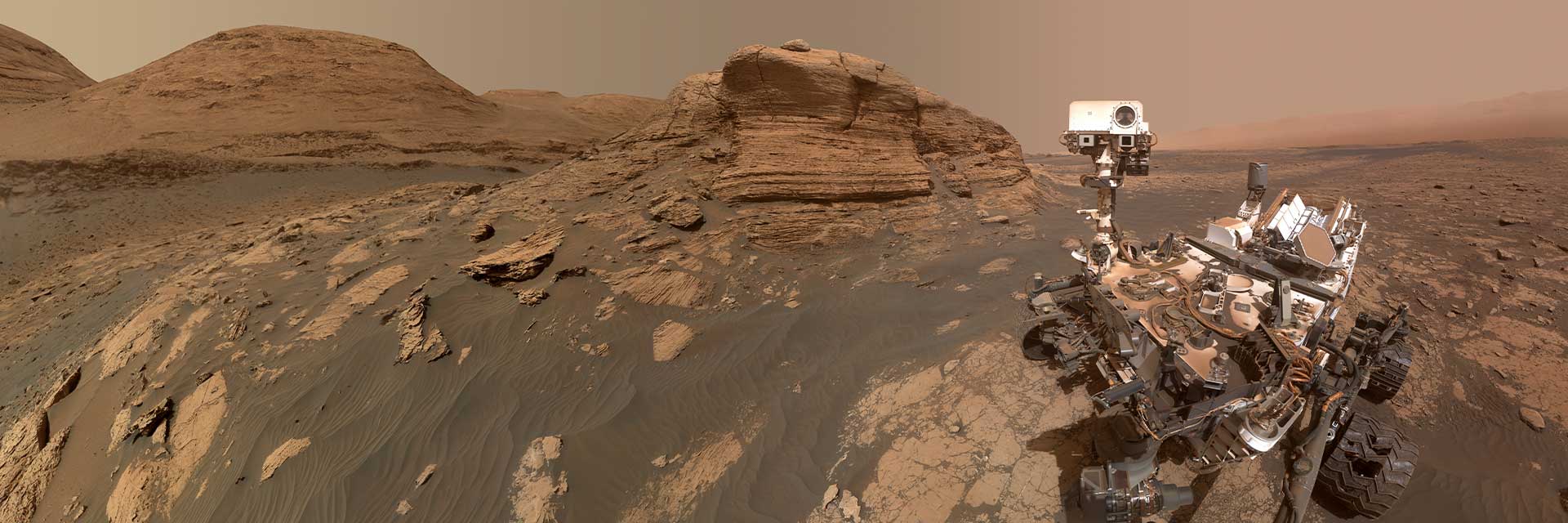

Looking into the future, Tate foresees NASA’s 3D printing initiative as one capability among a fleet of capabilities within in-space manufacturing.

“I think the goal in our deep space exploration, or habitation on a planetary surface, is to try and anticipate needs,” Tate said.

So what’s a space explorer far from Earth to do when faced with a critical broken tool?

“Cargo ships just can’t go make a quick run to deliver you something that you’ve run out of,” Tate said. Indeed, 3D printing, recycling and refining, she said, could be part of the tool kit to support the needs of faraway expeditions in sojourns to asteroids and Mars.

Additive manufacturing is one capability, among suites of capabilities, Tate said, “that can be potentially beneficial for exploring deeper into space.”