On Feb. 1, 2003, just minutes before space shuttle Columbia was due to touch down, the spacecraft suffered a catastrophic failure — all because a piece of foam broke off and knocked into the leading edge of its wing during launch 17 days earlier.

Getting to that answer — and ensuring that it couldn’t happen again — took months of investigation and the creation of tools that didn’t yet exist. One of those tools, a system of paired high-speed cameras and software that measures impact, has since proven useful here on the ground, ensuring safety and high performance in everything from running shoes to pickup trucks.

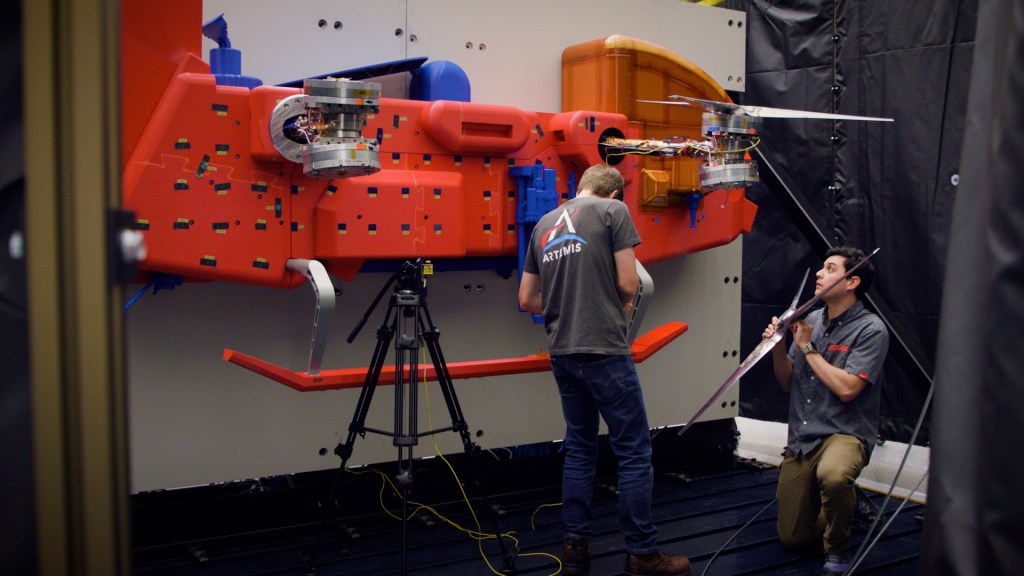

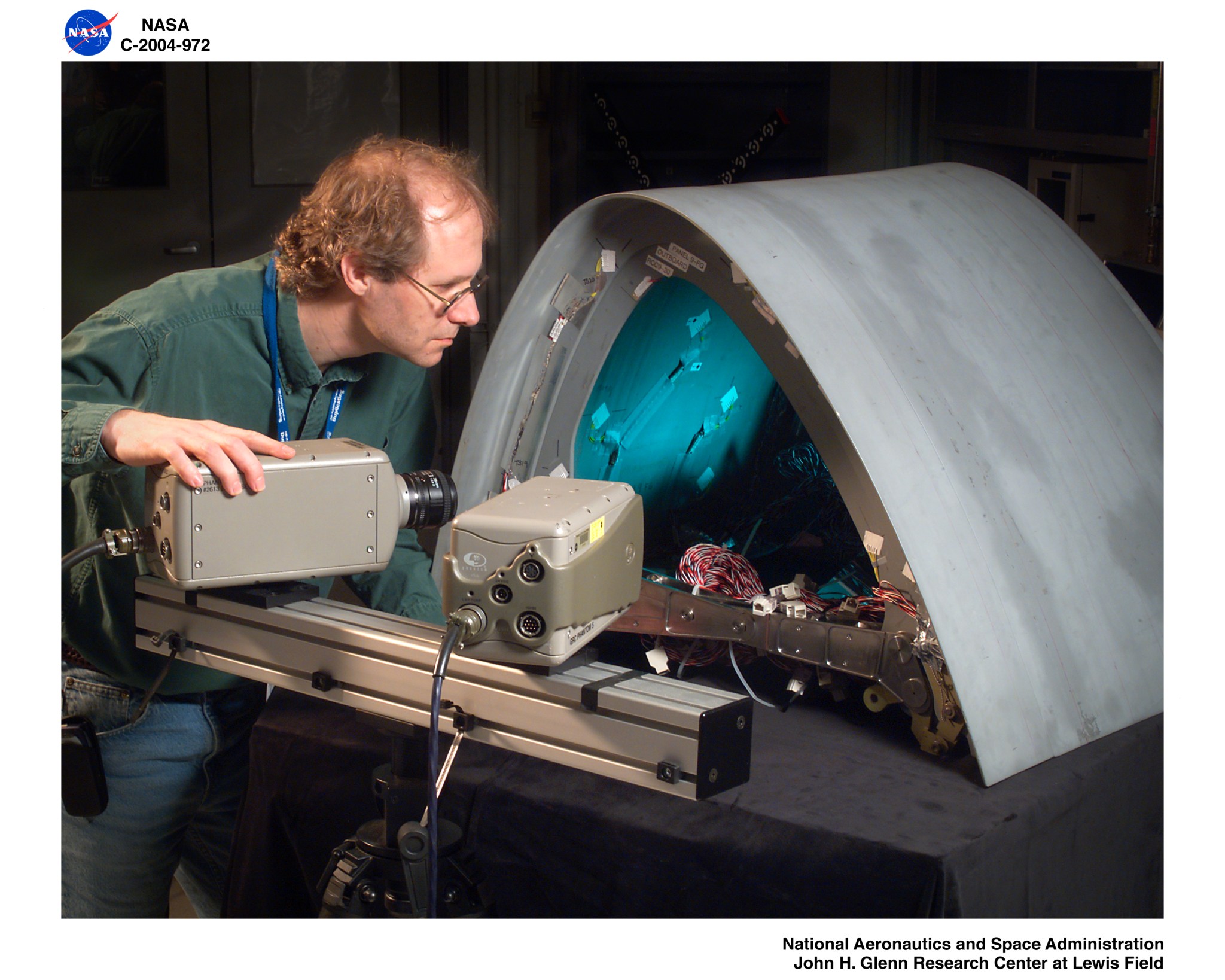

Stereo photogrammetry is “like using your two eyes to know where something is in 3D space,” explains John Tyson, president of Trilion Quality Systems, the company that built the high-speed system NASA used. “With two cameras, we can precisely measure if something comes closer to you or goes further away, and can estimate the distances it’s traveling.”

The technique was not new in 2003, when the Columbia investigation began, explains Matthew Melis from NASA’s Glenn Research Center, but it “didn’t have the ability to work at 30,000 frames per second,” which is the speed needed for “a ballistic event on par with what Columbia experienced.”

There were two problems to solve, Melis explains: they needed a technique for calibrating and synchronizing the high-speed cameras, and they needed an efficient way to transfer the images from the high-speed cameras into the software. Typically, cameras would save video directly to the computer, but high-speed cameras downloaded video to an onboard memory drive.

What’s Inside

Melis approached Trilion, the sole U.S. distributor of German-developed ARAMIS stereo photogrammetry software, asking the company, “What can you guys do to get us hooked up to high speed?” The timeline was short, because NASA was eager to get answers and make the changes needed to return the shuttle safely to flight.

“We spent about two months getting it working,” Tyson says. Since then, Trilion has continued to improve and streamline its high-speed system. Now, Tyson says, high-speed ARAMIS systems represent about 20 percent of Trilion’s business, and “it all started with NASA Glenn.”

One of the most important uses of high-speed stereo photogrammetry, or as Trilion calls its system, high-speed digital image correlation, is for materials testing. By understanding the materials better, Tyson says, manufacturers are able to improve performance and safety. For example, “years ago, cars were all just made of steel,” Tyson says. “Today there might be 50 different materials inside your car, each doing something different. That’s increased the safety of vehicles significantly, just by changing the materials.”

When Adidas wanted to design a new high-performance running shoe, it used the high-speed ARAMIS system to analyze Olympic marathoners’ feet as they hit the ground. “One of the things they saw was that a normal shoe constrains the ball of your foot and your Achilles tendon — as you’re running, your shoe is pushing against that tendon,” Tyson says. “So they made a V-shaped opening at the back of their shoe so the tendon is free to move.”

The shoe company also tested different materials to choose one that would allow the ball of the foot to expand with impact. “They studied the actual foot and then designed a shoe that would match the true motions of the athletes.”

Bona Fides

Boeing used Trilion’s systems to confirm its Dreamliner 787 was structurally sound. Ford used results from the system to ensure an aluminum F-150 truck body wouldn’t compromise the toughness of its trucks.

In addition to providing detailed and accurate measurements across a surface, Tyson says, the high-speed ARAMIS system saves money. According to an estimate from Boeing, using ARAMIS was 10 times cheaper than buying and replacing sensors and required a fiftieth of the labor.

It has sometimes been challenging to convince a new customer that a pair of cameras can measure tiny movements as accurately as sensors, Tyson says, but that’s where the company’s NASA bona fides have been a big help.

“There’s no question that that’s a big gold star on what we do: that we helped the Space shuttle fly again.”

NASA has a long history of transferring technology to the private sector. Each year, the agency’s Spinoff publication profiles about 50 NASA technologies that have transformed into commercial products and services, demonstrating the wider benefits of America’s investment in its space program. Spinoff is a publication of the Technology Transfer Program in NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.

To learn more about this NASA spinoff, read the original article from Spinoff 2018.

For more information on how NASA is bringing its technology down to Earth, visit