There are a lot of aspects about people that we don’t know. In fact, I read some things in your bio, that I didn’t know, like for example that you were founding director of Blue Marble, and that’s impressive. The idea of these interviews is to get to know people. We usually start by inquiring about your young years, childhood even, where you were born, where you grew up, what your family was about, and what might have potentially oriented you towards where you are today?

No path is linear but an interest in spaceflight has been a common thread throughout my life. I was born and raised in Switzerland, in Geneva. My father is originally from Kolkata, in India, and my mother is from Basel in Switzerland, so I’m a pure mutt.

The first recollection of space flight that I can remember was actually the Challenger accident in ’86. I was 6 years old and not really understanding what was going on, but it made the national news in Europe. I asked my parents: ‘what is going on? What happened?’ And they told me ‘People were going to space and there was an accident’ I didn’t even process the accident and I said, ‘People are going to space? What? Tell me more!’

Were your parents in Switzerland because of their profession?

Yes, both of my parents are not scientists, but both worked in scientific environments. My father worked for Lockheed-Martin in the Geneva office and my mother worked at CERN when they were building the Large Hadron Collider. As a kid, you get to go to your parents’ office, so I went to CERN and I went to Lockheed. At my dad’s office, there were models of airplanes and rockets, which got my mind spinning, not really thinking about career but just an interest as a kid. My parents noticed my interest in space, and I got a little astronomy book, and at 8 years old I got a little telescope, so I could look at the Moon and see for the first time the lunar topography, and see the Galilean satellites. I joined a local astronomy club, and by far I was the youngest member, by far, by decades! But it was cool. We went regularly to the observatory of the University of Geneva. In the mid-’90s, two astronomers from the University of Geneva discovered the first exoplanet, and that made the local news also. I’ve always enjoyed tinkering, so when it was time at the end of high school to decide what kind of career to follow, I decided on aerospace engineering. And because my father worked for Lockheed, it helped my eyes look towards the United States, so I ended up going to the U.S. for college, to get my degree and then I would go back to Europe. But life is unplannable and here I am, still in the U.S., 20 years later!

Did I misunderstand something in your bio about going to school in Spain?

That was later on, in graduate school. I spent 2 weeks in Spain with the NASA Astrobiology Institute, they host a summer school in Santander. It was an instrumental two weeks, in the sense that a lot of the friends and colleagues I have today I met them at these summer schools. I’m really sad to see the Iceland and Hawaii schools go. I hope NASA Astrobiology can maintain them in some way. They really benefitted me and others I know who attended them.

Where in the US did you do your university?

I went to the Florida Institute of Technology for my bachelor’s and I realized at the end of my bachelor’s that I had more questions than answers, so I decided to go to graduate school. I’ve always been very interested in space propulsion, so I ended up going to the University of Washington up in Seattle because they have a plasma physics program in their aerospace department. So that was the plan, to go and do that, but I only had funding for my first year, as a TA, but a Master’s is two years, so I needed to find funding for the second year. My advisor in the plasma program said “Look, I, unfortunately, don’t have funding for you for the second year”, so I said OK, I have to find a solution. I started knocking on a bunch of professor’s doors and one professor who did fluid mechanics and heat transfer said “Oh yeah, I have a potential project that you can work on for your Masters” and I said “great, that sounds fantastic!” so I switched from plasma physics to fluid dynamics, that is the physics of air and water essentially.

At the University of Washington, as part of that program, you have to take depth and breadth classes. Depth classes are your gas dynamics, fluid mechanics, computational, stuff like that. And the breadth classes are in other departments but with the same physics. University of Washington, lucky for me, has an atmospheric science department, so I took a class in planetary atmospheres, and my professor for that class was an astrobiologist, he integrated astrobiology into the planetary atmospheres class, and I said, “Oh my god, this is so cool!” Here I was 6 years into engineering school, and I told myself “what do I do?” A kind of a quarter-life crisis. I decided to finish my masters and start grad school all over again in earth science and astrobiology, and after 6 years I got the doctorate and then I came to Ames for my postdoc.

During my postdoc, I spent 3 months at the Stanford Graduate School of Business to earn a certificate in innovation and entrepreneurship, as I needed a new set of skills and networks to run Blue Marble Space.

I was about to ask if it was the postdoc that brought you to Ames?

Yes. I started graduate school in earth science knowing nothing about rocks, and I started my postdoc here at Ames also in a new discipline, bioenergetics. I think Tori, my postdoc advisor saw the breadth of my background in earth science and also having an engineering background probably helped because the postdoc was on quantifying the concept of habitability using tools from thermodynamics, which… builds character. For a long time, people had the idea that if there is water, then there is a good chance there is life, kind of a binary indicator. But it’s more complicated than that. Not all aqueous environments are friendly for the same biology so how do you put numbers to that? That was essentially the postdoc. I really enjoyed working with him, I really enjoyed the Ames environment, so I decided to stay and so far, it’s been working out.

So, you spent a couple of years here as a postdoc, and now you’ve been here almost 10 years. You talked a bit about the work you’ve been doing: how does it fit in with the NASA imperatives and missions and why is it important to the country and to humanity?

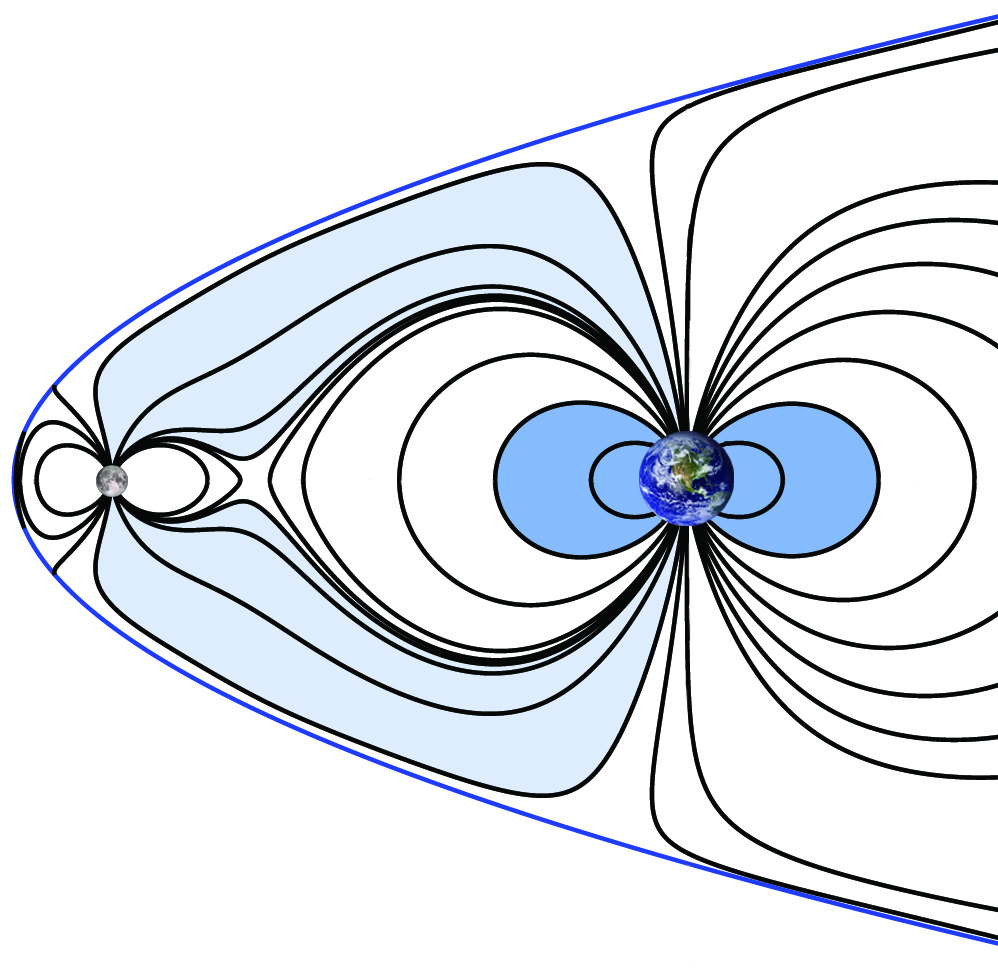

I have actually two parallel research tracks that have nothing to do with each other, although there are some crossovers. One of the tracks is Precambrian environments, the environments of early Earth and the other track is bioenergetics of water-rock systems. Let me tell you about the first one. The Precambrian is a time period way before the dinosaurs, when the planet was completely different than it is today: no grass, no animals, no trees, the Moon was closer, the Earth was spinning faster, the Sun was fainter yet more active in the extreme UV, so for all intent and purpose, the early Earth was an exoplanet. NASA has a very strong interest today in searching for life on exoplanets, but the best study-able exoplanet that we have is actually our own planet, billions of years ago, and that information is stored in the rocks that are that old. So it’s important to figure out what the environment was like, because it was so different than modern Earth, yet was very much alive.

More precisely, my small piece of the puzzle is trying to figure out what the air pressure was. Right now we have a certain amount of air pressure and the reason we, as humans, are able to breathe now and not die is because biology and Earth have co-evolved together, and since life has evolved for billions of years, Earth, and its atmosphere, have as well. So when we try to understand how to detect life on other worlds, it’s important to get snapshots of Earth through time because Earth has changed so much, and yet we know it hosted life, so the snapshots of Earth through time are essentially planets different from modern Earth that can sustain life.

That’s an interesting way of looking at it! Yes, indeed.

And it’s super fun! One of the aspects that I really like about geology, is being able to go to a landscape and then start reading the rocks, trying to figure out about what was going on, and read the landscape, ah, there was a river here, look at the rocks and pebbles, … astrobiology is cool because it’s not only hard science but also requires quite a bit of imagination, at least in the Earth science, to figure out what the environment of ancient Earth was like.

Is that what you mean by “rocks to life” science, learning about life through rocks?

I don’t really touch on life from the rocks directly, more like indirectly. I use the rocks as proxy for atmospheric constituents, and then you can think “well if the atmosphere was different, what were the geobiological interactions that led to the atmosphere that we can predict?”

Where are these rocks that you are looking at?

Some are in South Africa, and some are in Australia, but there are very old rocks all over the world. I saw some very nice ones in Canada for example. India as well has a bunch; they are kind of scattered all over the world.

How do you know they are so old?

Thankfully I stand on the shoulders of giants. There have been people before me who have done detailed mapping of where different rocks are. You can date the rocks using radioactive element decay. Carbon dating is one you hear about a lot, but that only works for ages of fifteen thousand years, so if you want to go billions of years you have to use uranium-lead. People are very good at that. It’s not what I do, but I trust them.

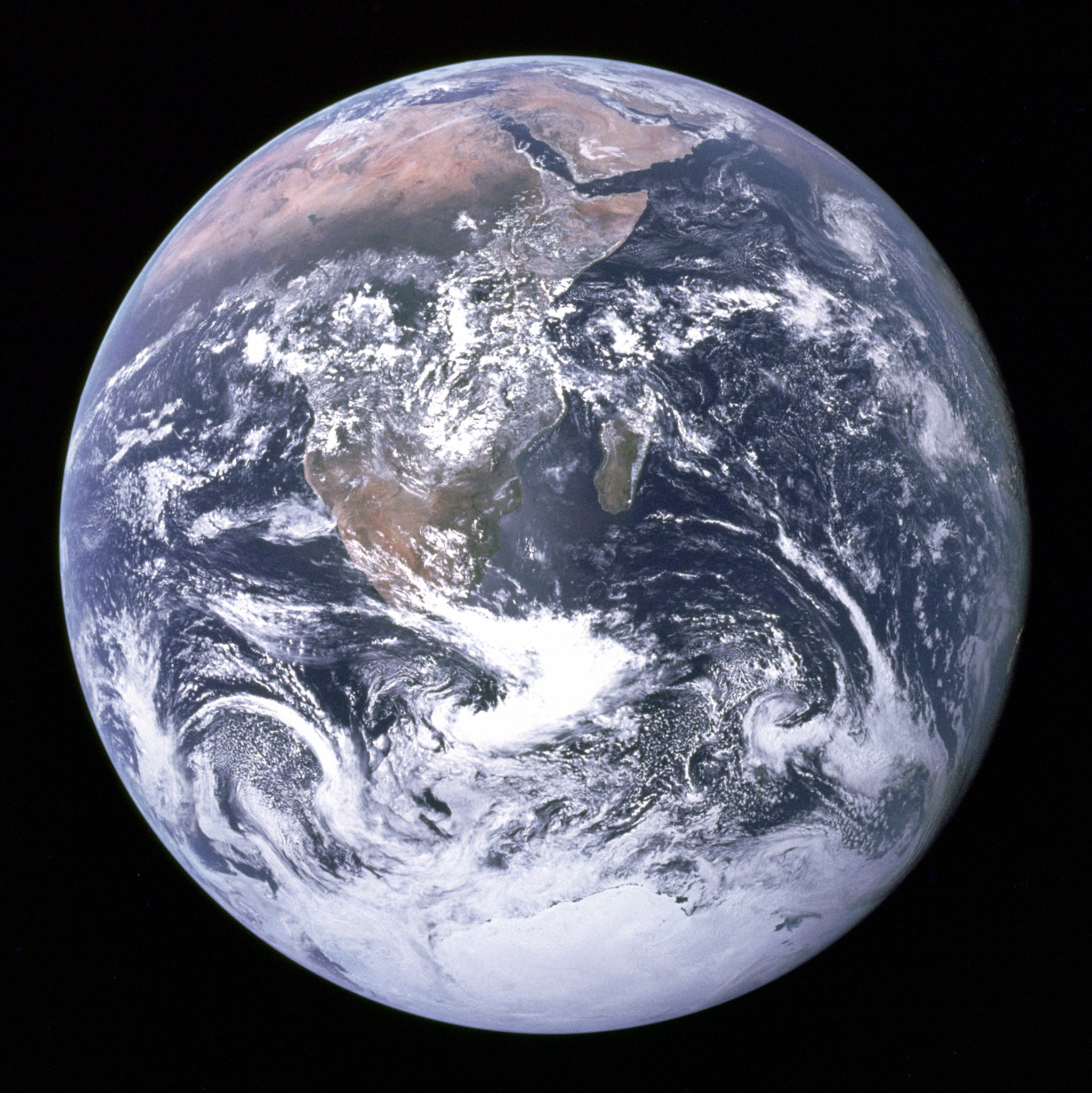

From the taxpayer’s point of view, understanding whether or not we are alone in the universe is probably one of the most important questions that we can ask as a society because whatever the answer is, it is fundamental and will teach us a lot about how to behave as humans. If the answer is no, there is no life beyond Earth, that means that we humans are the guardians of intelligence in the galaxy, and that’s one hell of a responsibility to hold. What will it take for us as a civilization to measure up to this realization? When you look at Earth from space, it’s a big deal that we are here, and I think very few people have this cosmic perspective of our planet. It makes sense, we all get caught up in our daily problems, and that’s fine, but I think it’s important sometimes to step back and realize, as Carl Sagan said, “that we’re like the squabbles of mites on a plum”. Conversely, if we are not alone in the universe, what does it mean to be human? Would it be the detection of extraterrestrial life that will make humanity realize that they are humans first, and then Americans, Chinese, Muslim, Christian, whatever? It is to realize that the beauty of humanity lies in its diversity at the end of the day, and I wonder if it will require the detection of extraterrestrial life to get to that level of maturity.

We are celebrating this month the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing. And it is clear to me from some of these documentaries that it really depended upon popular support, and we had that popular support partly because of a political race we were having with the Russians to see who could do it first, but NASA got lots of money to do that, and when we finally did it then the money kind of dropped off because we weren’t in that race anymore. You have to be doing something really important in the public interest and I don’t know of a question that is more of interest to thinking people than understanding life on Earth, and potentially life elsewhere.

You don’t need a degree in rocket science to think about these questions deeply and how they affect you emotionally. We all have laid down in a field and looked at the stars in the night sky and asked those questions. It connects all of us and it’s incredible to be alive in this time period where we can actually potentially seek the answers scientifically in the coming decades if not sooner. It’s really exciting.

Any interesting findings so far in your research?

Well, in the first branch of my research, what we seem to have found is that the air pressure, at least on Earth prior to the rise of oxygen, was less than it is today, which it’s surprising, probably half of what it is today. It’s not crazy, in the sense that three years ago I drove up to a mountain pass in the Himalayas, in Ladakh, which was almost at 6,000 meters, and at the top of that pass, the air pressure was half what it is on the surface. I couldn’t run a marathon there, but I wasn’t dying, so it’s not unreasonable. But it has important consequences because most of the air pressure today is due to nitrogen, 79%, so where did it go back then? The answer is in the geobiological system. Again Earth and life have been co-evolving together, and that has caused the planet to change. As biology evolved, Earth adapted, or the Earth changed and pushed biology to evolve. This back and forth has been going continuously over billions of years.

The rise of oxygen happened roughly halfway through our planet’s history. Early on when the Earth was born, the air pressure was probably higher, because everything was being degassed as the planet was so hot. When life kicked into gear, it changed the atmosphere, and it has been changing and continues to change the atmosphere.

When you said life, you mean animals or plants?

When I talked about life in the ancient Earth, I mean microbes. Animals and plants are pretty recent, relative to microbes. This timescale is important.

I present the time scale of Earth history in many of my science communications talks. The Earth is 4.5 billion years old but what does that really mean? Most people can’t really appreciate that time scale. One good example is to take the length of a table that is in front of you, we can take this one for example (points to table). 4.5 billion years will be the full table, if you divide that by 2, roughly 2.2 billion years, that is roughly where oxygen started accumulating. All this time period (rest of the table) there was no oxygen, so it’s essentially a different planet compared to modern Earth. If you divide that by two again, 1.2 billion years ago, then divide that by about two, 540 million years ago, this is roughly the rise of animals that you could see with your naked eye. Divide that by about two again, 250 million years ago, that’s when the first dinosaurs appear in the fossil record, divide that by two, 125 million years, divide that by two 65 million years ago, here (almost at the edge of the table) is when the dinosaur became extinct, and people think dinosaurs as being extremely old, but look how close I am to the edge! (gestures). This is our history. We are here, at the very tip and we are changing the planet in a timespan equivalent to the width of a hair on this table, in ways that we haven’t seen before. It gives you perspective.

Microbes changed the state of the world in a dramatic sense 2 ½ billion years ago with the rise of oxygen, in a way that really affected the evolution of life on Earth and Earth itself, but they didn’t know what were they doing right? We are affecting our planet today with one hell of a brain to understand the consequences. What will it take for us to get it together? So maybe astrobiology insight can help.

What’s a typical day like for you?

No day is typical, in the sense that I’m a soft money scientist through Blue Marble Space, so my income depends on the grants that I bring in and Ames projects I can work on. Since I don’t have enough good ideas to fund myself 100% on grants, I wear multiple hats. That’s a common modus operandi for most scientists though. Despite that, I try very hard to carve science time; that for me is really important, but I also run a research associateship program here at NASA Ames called the Young Scientist Program which has been very rewarding; we work primarily with the Space Biosciences Research Branch, Code SCR, and manage a lot of their student researchers. SSX has been very supportive of this program as well. We built a program that is very holistic. For us It’s not about pushing paperwork, it’s about building a community of early career researchers, and giving them the tools to not only become excellent scientist, but excellent at science in the twenty-first century, which is why we have been heavily emphasizing effective communication training, as well as training in ethical thought.

You were mentioning the importance of science to taxpayers? What we are really pushing hard for our students to understand is that funding going towards their research and paying their salary ultimately comes from taxpayers. So, it is the responsibility of scientists, because they are taxpayer-funded, to return that information to the public; that’s one of the many reasons why science communication is so important. We bring in faculty from the Stanford School of Business to give them a workshop on effective communication where they learn the theory behind effective speaking and how to give a presentation. If you are here on August 15th in the N245 auditorium, we are going to have a Night of Science, it’s going to be a beautiful evening!

I do my science, I work on Ames projects, I run the research associateship program, and I also run Blue Marble Space. It’s only 10 years old, so it still has a ways to go in order to be able to sustain a full salary for an executive. Within my science I don’t have one grant that covers all my science, no science grants covers 100% of a scientist’s time. On some grants I’m funded 20%, some grants 10%, some 25%, so every day is different, time management is a skill, that’s why no day is the same.

I spend a lot of time communicating with colleagues, sometimes I disconnect from the world and focus on computation, sometimes I have to think ‘okay, there is a proposal call coming up, do I have a good idea that I can put down?’ Then I connect with collaborators to see if people are interested in submitting with me, as it’s rare that someone has all the knowledge necessary to submit a proposal.

This rhythm can be stressful but it’s very rewarding at the same time. I’m at a point in my career where I can still maintain that level of energy and do all these different things. In fact, I really enjoy having several projects going in parallel. I would get so bored if I only had one task, so it’s good for me to float around like that.

Do you do fieldwork?

Yes, but not as much as I would like to, because management is taking a lot of time and a lot of responsibilities with all the students in our program now. But yes, the best of science is in the field and behind a computer. The lab part I’ve essentially stopped. I can do it but it’s not my strength, and there are only so many hours in a day. I’m in my element in the field. I’ve done fieldwork all over the world: Australia, New Zealand, Iceland, Yellowstone, we even have a field site north of Napa Valley, there are some rocks there that are relevant to the second branch of what I do. It’s nice to go to a field site when you have to cross Napa to get there (laughs)!

Was Ladakh too part of that?

Yes, that was taking local scientists to the field, explaining to them the relevance of the sites they have locally to astrobiology, and bringing in teachers and connecting with the local schools there. It was awesome, two powerful weeks.

What do you enjoy most and least about your job?

By far what I prefer is interacting with the next generation of scientists, the highlight of my postdoc for example, which led me to push towards making a career in the nonprofit sector was going to a local elementary school. I told them about science, I had not said two sentences before all the arms were up, the eyes were huge, ‘what about this? and what about that?’ Their enthusiasm feeds mine; it reminds me of why I became a scientist. It’s often easy in science to get lost in your equations, but when you connect with the next generation you can see their enthusiasm and you can see how they want to change the world. Your task then becomes how to help them with their confidence to do it and be a good mentor. Not an advisor, a mentor. It’s just so rewarding.

What advice would you offer them if they want a career like yours?

Stay curious, frankly. Don’t pigeonhole yourself into what your parents, or what society thinks you should be doing. There is no such thing as a biologist, there is not a this nor a that. The human mind is capable of integrating so many different elements of life, of knowledge, and so one must build a career based on what is interesting to you. I’ll emphasize this again: do not pigeonhole yourself. Academia is lagging behind that philosophy because it is still very much structured into departments, but astrobiology is at the forefront of education because they stress interdisciplinary and interdepartmental collaborations in graduate school.

I was very lucky to end up at the University of Washington because I went there for plasma physics in the aerospace program, but they had a wonderful, actually one of the leading astrobiology programs in the country, so I was very fortunate to be there, even though I was there for completely different reasons. And I haven’t looked back since making this decision after my Masters to start grad school again.

And what is the least? The paperwork?

Yeah, but working with the government is a blessing in the sense that NASA Ames has been extremely supportive of my work on Blue Marble Space. I feel very privileged to be here, not only to do my science with collaborators at Ames but also tickle my entrepreneurial spirit and Ames has been very supportive of that. But the government is very bureaucratic, so to get stuff efficiently processed you need to know the system very well and that takes time, and that’s fine, it’s just how the beast works. Sometimes it’s easy to get frustrated because paperwork takes a long time, it should have gone to A instead of B, but I see it as a value opportunity. Where can we come in as Blue Marble Space and offer a solution to save people time and hassle? The Young Scientist Program emerged as a solution to a problem that Ames was having, bringing early career researchers to help, so we developed this program, and it’s been a cool partnership between the center and our non-profit.

Have you ever thought if you weren’t a NASA research scientist what your dream job might be?

Well, I almost have my dream job so that’s a tough one! Another corollary question could be, if you were born in the 1600s what would you be doing? I have an interest in horology.

What’s that?

Watchmaking, watch assembly, the mechanics of it.

Isn’t Switzerland famous for watches? Is there a connection there?

Probably! I enjoy watch pieces; this one is cool (points to his own watch) because the second hand takes 58 seconds to go one revolution. When it reaches 12, it will stop and then you will see the minute hand go. All the train stations in Switzerland have this type of clock.

The Swiss run the best ones, on time! in watches and trains too.

It’s funny when the trains run only a few minutes late, the conductors are always so apologetic, “we will be arriving to the station 3 minutes late, I’m really sorry for the inconvenience”! Here I use Caltrain almost every day, they are good, I’m not going to bash Caltrain, although diesel engines in the 21st century in Silicon Valley? But they are electrifying…

You might know how the long-distance trains, at least here, deal with daylight saving time?

No.

When the clock is turned backward, in the fall, trains, if they are running on time, actually stop for an hour. It sounds crazy. When the clock is turned forward in the spring, they just keep going and try to make it up, but in the fall if they are on time, which is not always the case, they stop, because it’s cheaper to do that than to actually change all the timetables. [https://onemileatatime.com/amtrak-deal-time-changes/} I always really wanted a watch with a second hand, I like precision, I like the atomic clocks that run off the radio signals.

Then you should check out this company called Zenith; they have a new way of keeping time. It’s no longer using the springs, and the wheels and the escapement. It’s a physical concept that I’m not familiar with, but essentially, they have this piece in there that vibrates at a really high rate, it’s a new way of doing a mechanical watch. That blows my mind!

That’s fascinating because time plays such a critical part in GPS, for example, but 250 years ago in figuring out longitude at sea.

That’s where the real innovations in mechanical watches came about, solving the problem of longitude. The innovations are actually British, but the Swiss mastered the way to make them of high quality in very large numbers.

So, do you build them then?

No, I assemble them, I don’t build the individual springs and wheels. Right now it’s just a hobby. I have a friend, who is an artist (also as a hobby) that is going to work on doing some really nice dials, I’m sure it’s going to look quite nice when we are done. Because I spend a lot of time on my computer, I miss doing things with my hands, and I live in an apartment, so I need small projects!

Do you want to share something about your life, your family, pets, trips?

I live in San Francisco, I’m a member of the Bay Area Orienteering Club. Orienteering is a sport that I really enjoy doing, it’s a good way to learn about the different parks in the Bay Area, and it’s a sport that also requires your head. You don’t know where you are going when you start the race but as soon as the clock begins, you see your map of the area, you have a compass, you have points on the map where you need to go. Depending on the terrain you have a landmark on the map that’s easy to find, and you can find your points, sometimes you have to rely on the compass. It’s a really cool way to be outside, and exercising while using your head a little bit. Horology is a fairly new interest. I’ve been interested in watches for a long time, but actually getting a watch and playing with it is a fairly new hobby.

To read your bio, you’ve been to a lot of places. *

Yes, and many of my travels are motivated by ancient civilizations, I think that human history has a lot to teach us, and it’s not taught enough in terms of the lessons learned through society, so I enjoy going to countries which have hosted fantastic civilizations, just to see the ruins and try to understand the history, why was it demised and so on. I’ve been to Cambodia, to Japan, to India, those are major civilizations that flourished. If you lived in Europe two thousand years ago, Rome was all powerful, and you would never have thought that a civilization with the power of Rome, would collapse, yet it did. We may feel that we are invincible now, but we are not. It’s very different times of course, but humans are humans, we are still the same in that sense, only technology has changed, and hopefully one day our awareness of the fragility of the Earth and what we are doing to it will make us realize that we are threatening the prosperity of our current civilization.

Climate change bothers me a lot. Even if we stopped emitting CO2 today, sea levels will rise and if sea levels rise it will cause climate refugees in numbers that we’ve not seen before. Then it becomes a lifeboat ethic, which we are struggling with within the U.S. now in terms of immigration. Do we let people in? Of course we do, we have to help people, right? But the truth is the country has a carrying capacity, you can’t open doors completely as much as we want to, and finding the right middle ground is tough. As you see in the news, it’s a tough conversation to have and it’s just going to get worse with climate change. I wish more scientists were going to Congress, contacting their Congresspeople and really making this statement in ways that are not patronizing. It’s not public outreach, it’s community engagement, and there’s a difference.

Public outreach is a statement where “now I’m talking to the public, therefore I’m not part of the public”, and then doing outreach, there is no back and forth communication, which is why I tend to use “community engagement” now, because we are part of the community as well, as scientists and politicians. We need to learn to talk the same language, it shouldn’t be an “us versus them”. We are both trying to solve solutions, in the same way, we both have different experiences and ways of solving these problems, so let’s join forces. That’s something that I personally will want to do more in the next few years, that is getting more involved as a voice for science. The AGU (American Geophysical Union) has a fantastic “Voices for Science” program, and I was part of their first cohort last year. And through that, I’ve been to DC and I’ve been in touch with some of my representatives. The Earth is changing and there needs to be a more trustworthy conversation between policymakers and scientists to find solutions. We cannot put politics over the health of our planet.

What do you do for fun?

All the things I already mentioned, orienteering, etc. Living in San Francisco, I enjoy exploring the city for fun “hole in the wall” restaurants and bars in the different neighborhoods. I try to go back to Switzerland at least once or twice a year to spend time with family, that’s really important to me.

So, they are still there?

Yes, everyone is there, and my sister is coming tomorrow. There are four of us, I’m the oldest, and everybody else lives in Switzerland. I’m actually going back at the end of August, I’m excited about that.

Have you ever thought about what or who inspires you?

Making the world a better place. I was a Boy Scout when I was a kid and when you go camping you always leave your campsite in better condition than when you arrived, and I want to do that for our planet. I’m sure you’ve heard of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. At the tip of that is self-actualization, meaning you have reached a point where you can achieve your fullest potential. There is some research out of Berkeley that shows that people who feel self-actualized have a connectedness with the planet. So my goal, and that of Blue Marble Space is to pull however we can people that we interact with up that pyramid so that they can feel self-actualized. A lot of good would happen if humans saw each other as humans, first and foremost. They would feel that they are part of a unique system, have a sense of oneness with the world, and that’s what pushed me in first place to start Blue Marble Space. It started as a vision of the astronauts wearing a symbol of the Earth instead of their national countries. When humanity returns to the Moon, I hope it’s not going to be another flag-planting. It would be so powerful if they put a flag that has the Earth on it. Everybody in the world will know who planted it, it’s not going to be a question of nationality, but the power of that statement will be so noble and refreshing in terms of humanity exploring. Astronauts are ambassadors of planet Earth, after all.

They made a point in the Apollo XI mission where the put a plaque on the moon that says, “men from the planet earth first set foot upon the moon. We came in peace for all mankind”

I wish they had used “humankind”, but okay.

I’m very optimistic about humans, I think the climate change process will be a painful one to go through, but humans are very capable of finding solutions when there is a problem, but they won’t do anything prior to the problem, this is just how we operate.

So what really inspires me, come to think of it, is the image of Earth from space. That kind of changed the direction of who I am, and how I study, and how I decided to lead my professional life. I could have decided to become a professor, but the non-profit route echoed more with myself and pulling people up that hierarchy of needs to the point where they can feel that they can achieve their full potential is something that I feel very passionate about. That’s what I do with the students in our program here, and I encourage them to do that in their local communities as well. And then if the research is correct and you have this feeling of oneness with the Earth then perhaps that could be a practical way of reaching the state where we see ourselves as humans first. So yeah, what inspires me I think is our own planet. In its own way, it has adapted to many many changes, hanging in the void of space, and so far so good, it’s still a beautiful planet.

We actually ask if there is a favorite space image, and you have already answered that. Also, if you have a favorite quotation that has value to you.

It’s the blue marble picture taken from the Apollo 17 when the astronauts were coming back from the Moon.

It could hardly be anything else!

Last year I published a paper called “Common identity as a step to civilization longevity” where I put all these thoughts on paper, about the importance of training humans at an early age to have this perspective of seeing Earth from space, because if you don’t have a different perspective than your current viewpoint, when you interact with people with a different perspective, you do two things: you either beat them up or you don’t and when you don’t you tolerate them. I have heard very inspiring astronauts say, “We need to tolerate each other more”. But toleration is just the first step in civility. Tolerating means that you don’t really embrace the conversation. Having a different perspective whether it be scientific or religious or philosophical, all of these have a lot of historical baggage to them, whereas the perspective of Earth from space is completely neutral, and everybody can relate to it. If you teach kids, hey, if you look at what you do to others from that cosmic perspective, when you meet somebody that sees the world differently than you do, you can go back to this perspective of seeing the world because they have it as well, and that enables the beginning of a conversation. Let’s move beyond tolerating one another.

I also feel like we need to spend time in school teaching about how to handle emotions, because school and society are driven by teaching an old scheme, with science, engineering, the arts, and math as the focus, and to become good individuals. But there is no formal concept of teachings kids how to be effective in a global society and handling emotions is part of that. Currently, we learn how to handle emotions through life experiences, which sucks because we all have fallen on our own faces as a result, but such handling can be taught: how to listen to somebody, how to not have your logic be clouded by the emotions, there is a lot of literature on that.

What are you reading these days?

I just finished The Three-Body Problem, have you read that? The Three-Body Problem is actually a problem in physics when you have three gravitational objects, like stars that are revolving around each other, and you have a planet. The path the planet will take is not predictable by mathematics. So this book is about a civilization that lives on one of these planets and they have eras of chaos, I don’t want to give up too much so I won’t spoil the book, because you should read it. It’s by a Chinese author, one of the first Chinese sci-fi stories that have been translated into English, and it’s a best seller. At the same time, it is written from the perspective of these scientists living during the cultural revolution in China, which is refreshingly different. I finished it last week. I was also looking at the book by George Daniels, probably the best 20th-century watchmaker, on watchmaking. It’s an incredibly detailed book, I had no idea how much it takes to build a watch. It’s amazing when you have people who are experts on any one topic, the amount of knowledge they acquire at the end of a lifetime, it’s gorgeous.

And music?

Depends on the mood, I can go from Metallica to Beethoven! I like 80’s rock, if it’s one genre, it will be 80’s Rock, Deep Purple and stuff like that.

This has been a wonderful conversation.

Thank you, we appreciate it.

You’re welcome!