We like to begin with having you talk a little bit about your younger life, your childhood, where you’re from and a little bit about your life experience early on, and if there might have been anything about your early life that oriented you toward where you are today in terms of your NASA career.

Absolutely! First, thank you so much. I think this is a wonderful activity that allows our group and others at Ames to look at these interviews and get to know more about our scientists and their background. It’s inspiring to find common threads, common stories.

I grew up in India, I was born in Udaipur, it’s a historical city in the state of Rajasthan, which is itself a historical state in the northwest part of India. It’s one of those places that you see on the documentaries, like on BBC America, with these bright colors and palaces.

I spent all my childhood in this beautiful city of Udaipur until I went to college, to Mumbai, they used to call it Bombay them, it’s now called Mumbai. I was seventeen when I left home. Growing up in Udaipur was just an absolute pleasure, I realize that now. I grew up in a big family and my family was very progressive, very intellectual. Now all my cousins and my brothers – we grew up together- have spread out, but most of us are in the U.S.

I think when I was about fifteen years old, this would be the 10th grade in India, you have these national level exams, after which you have to pick a broad field of studies such as science or arts. You are kind of locked in at this point. If you don’t take sciences at that point, then you don’t get the opportunity to go into sciences later. I was an average student until then, and mostly because I didn’t think that I had found my calling. I liked being in school, I liked my friends, but nothing drew me into academics until I was fifteen. There was a chapter in our science book, it was about astronomy. It was about distance scales in the universe, you know how far things are from each other. And when I read that, I was just completely blown away, fascinated, to realize how insignificant we are, in comparison to the whole universe. And that just turned something on in me. I went to my brother, who was four years older than me and who was a science major, and I asked him “What will it take me to pursue this? I want to learn more about this subject.” And he said, “Well you’ll have to do a Ph.D., and for that, you’ll have to go to America.” And I said, “Well, OK, that’s what I will do” (laughs). That’s when it all started for me. This was interesting in that it came at a time where I had the choice, and I went into sciences. And I was an average student until I was fifteen, and then I was first in the class after that. That is the leap that happens when you get into something that you’re interested in. That is something that I can never forget because that’s when it all started for me.

I was a very independent person so after that, I told my parents I needed to leave my hometown and pursue sciences. I went to Mumbai for my undergraduate. At that time String Theory was very popular, particle physics, and I was fascinated, so I took a little bit of a detour after I finished my undergraduate degree and decided to go to England to Durham University for my Master’s degree. And instead of pursuing astrophysics at the time, I decided to learn about particle physics, just for a year and a half. I was still exposed to astrophysics here and there, that was still what I was always motivated by. Towards the end of my Master’s degree, I applied for the Ph.D. program in the U.S., at Rutgers University. I came to Rutgers and continued string theory for a year and then I switched to astrophysics. And since then, I’ve never looked back!

It is fascinating that you had this epiphany when you were fifteen and knew what you wanted to pursue; you were fortunate that that happened. A lot of people don’t have that or don’t have it early enough to actually capitalize on it.

Oh yeah, and one thing I want to say is that support from your family is everything. When you find something big that you want to pursue and there is full support around you, it can make your journey easier. I’m very grateful for that. My parents said, “OK, if this is what you want to do then pursue it and see how it goes”. And they found that I was so motivated that I set up my own career after that. I told them that I got selected for a degree in England and that I got selected for a Ph.D. program!

Were your parents science-minded in some way, or scholarly minded, or your brothers and sisters? Did they have a similar something that impelled them toward where they are today?

My dad did not have a science background; the business he runs has a scientific component to it. He is very scholarly, he reads about everything. And two of his brothers, my uncles, had engineering backgrounds. And another uncle, who is a professor in the U.S., had a very academic career. My brother, who I am very close to, went to pursue a degree in engineering and he was always interested in astrophysics, he is now an environmental scientist. We always encouraged each other.

My mom did not go to college and does not have a science background, but she is a very intelligent, very caring, and very forward looking person.

I think one more thing I should mention are some of the constraints that I did have to overcome, in that I was a woman growing up in India, and leaving home is not something that is considered an easy thing to do. For my parents, it was very difficult. My father wanted to make sure that I had all the opportunities that anybody else had. He did not see the difference between men and women, but he was surrounded by a society that did. My mother (like the society around her) was very afraid of me leaving without being married. I think it was a huge change on their part. And this would be difficult for them for a good five years after that.

My parents weren’t worried, but I know that they would be surrounded by people who didn’t feel that way. And one thing that I should also mention is that going to Bombay was not so much of a big deal, because that was a city in India that was approachable, but going to England, leaving my home country, this became a big issue. And I must say that I think was the first woman in my community to ever step out of the country without being married. At the time it was a drop in the ocean, but it changed everything for my community. Now there are so many women who are allowed to leave, and it’s not a problem to leave the country without being married and to pursue degrees outside of the country. You don’t even realize what you did until you did it!

Wow! You’re a pioneer!

You know, I didn’t realize it until much later. I went to England, it was hard for my parents, but I did it. I came back home after a year and I had some people who wanted to talk to me at home. And they said, “Naseem, what you did just by leaving the country, it changed life for us. Our parents don’t think it’s impossible anymore”.

And did you find when you went to England and later to America, that you could understand their concerns about stepping outside of the culture but that their concerns didn’t materialize for you?

Exactly! I did lead by example, and then I will go back home and talk to people who were skeptical, and they realized “Oh! Nothing changed. She is doing really well; she’s progressing really well”. People think that women on their own can be easily influenced. It really depends on an individual person, it doesn’t matter if you’re from India, you can be influenced no matter where you are from. But I wasn’t leaving India to be influenced, I was leaving to pursue something that I was very driven. And I told them “Look, we have so much family in the U.S. I have such a good support system.” I had uncles and aunts here and by going back-and-forth, that’s what gave them more confidence, and when more people left the country and then went back, that gave them more and more confidence. And none of them did anything really bad, or nothing bad happened to them (laughs).

Did any of your siblings follow in your tracks and leave the country? From your family and your community?

Oh yeah, a lot of them.

Everything has changed in the last two years since I joined NASA. The community back in Udaipur I grew up in see me as part of the NASA family. I am a NASA project scientist and it has changed the world in my community. They are so proud of me, no matter what they believed at the time or what they may have been concerned about. I’m like their daughter! They just fully support me and very proud of me.

So now you’ve gotten into Rutgers and you’ve got your Ph.D. and at some point, there became a connection with NASA that ultimately got you here to Ames, so do you want to talk a little about how that came about?

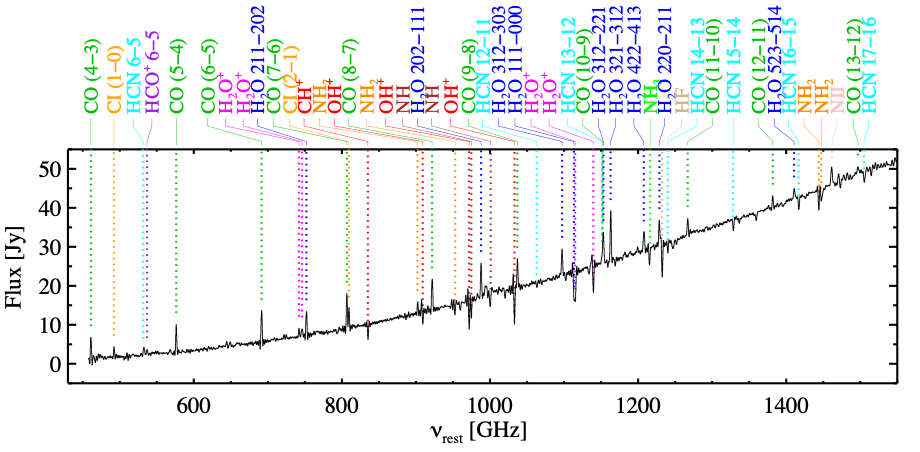

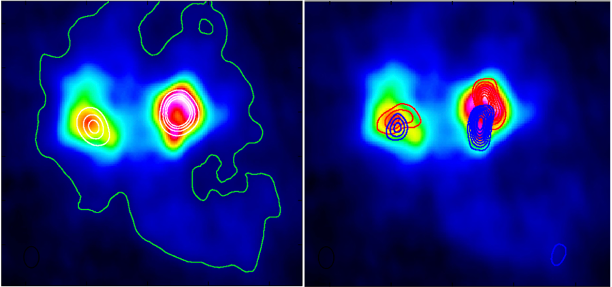

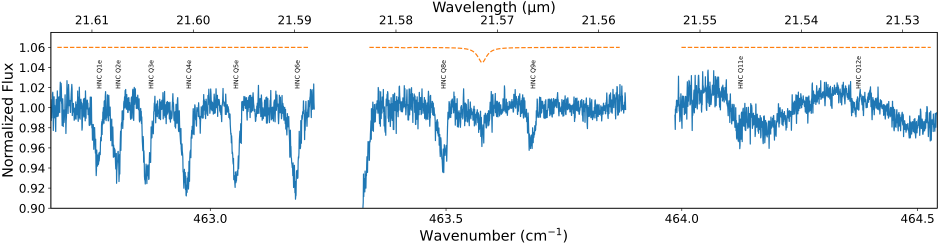

Absolutely. At Rutgers, I was mostly associated with optical astronomy. When I was finishing my Ph.D., submillimeter astronomy and far-infrared were becoming very popular with the Herschel mission* and ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array)** coming online. I decided to take a detour in my research, and I applied for a position as a Herschel postdoc at the University of Colorado, Boulder. At that time I had met my future husband as well and he also got a postdoc position at the University of Colorado, Boulder, so I moved to Boulder to pursue a Herschel postdoc and the month after I finished my Ph.D. was when the Herschel mission launched, so it was just very inspiring, it was the perfect opportunity, for which I’m very grateful. I joined the group in Boulder and within six months, I had the first data from Herschel in my hands, and I got to work on a galaxy called Arp 220. It is the nearest ultra-luminous infrared galaxy, a template galaxy to better understand galaxies that were forming in the early universe. Arp 220 is a system where two gas-rich galaxies are merging. This system is at the very end of their merger and so there is an intense burst of star formation going on and that is what’s thought to produce the large amount of infrared luminosity and that’s why they are called ultra-luminous infrared galaxies. Arp 220 was like hitting the gold mine, to have the first spectra of this galaxy in the submillimeter, because Herschel opened up the universe in the submillimeter for the first time. I got the spectra, and it was wonderful! This was where my interest in spectroscopy and astrochemistry started as well I continue to pursue now with SOFIA and ALMA.

After finishing two years of my postdoc during which my husband and I welcomed our first child, my husband got a position at SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, a NASA airborne telescope) at Ames. Fortuitously, I had just won a NASA ROSES grant to do independent research on my Herschel work and I was able to move to Ames with that grant, so we moved to the Bay Area. I emailed Jessie Dotson, the branch chief at that time and she was extremely welcoming and did everything she could to help me get to Ames. I also thought that my skills will be helpful to the astrophysics group at Ames as there weren’t many infrared observers in that group using Herschel, ALMA, and SOFIA.

About how long ago was that?

This was January of 2013.

So not all that long ago.

After a year and a half of being at Ames, I applied for the NPP. I got to know people in the branch, and I found out how I could contribute, and figured out a project with scientists working in the laboratory astrophysics group. I was primarily collaborating with Tim Lee, Partha [Bera] and Xinchuan [Huang], and Sean Colgan. I got the NPP and started working in the NASA postdoc position. And towards the end of my NASA postdoc, the project scientist of SOFIA at the time [Kimberly Ennico-Smith] asked me if I wanted to assist her and become the associate project scientist for 50% of my time because she needed my expertise, someone who was connected to the SOFIA Observatory as a user. I was a little hesitant to join as I knew it will be a huge time commitment while also caring for a 1yr old and a 5yr old. I am so glad I took that opportunity. SOFIA really launched my career at NASA. I had started using SOFIA right after my Ph.D. to complement my Herschel and ALMA work. I joined SOFIA in the beginning as a contractor, on a coop from BAERI. And then came the opportunity for me to become a civil servant on the SOFIA project. That was about 1.5 years ago. Around the same time, my husband left SOFIA to work on another exciting NASA mission at Lockheed Martin.

Had you already become a U.S. citizen?

I became a U.S. citizen in 2014.

And did that create any stir in your family? Or did they understand why you did that?

No, my family never had any issues with that and culturally it has not been an issue. You have to give up your Indian citizenship to a certain level, you can get overseas citizenship but it’s not with full rights. But that was not an issue.

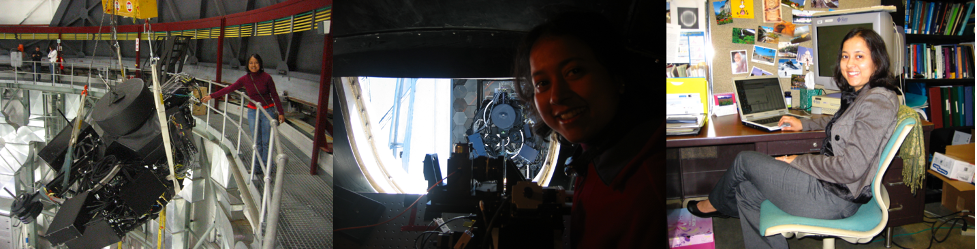

Joining SOFIA with Kimberly was an eye-opening experience for me because as a scientist, just as an academic scientist, you are focused on your research but when you get on a mission, it’s a whole different thing. Everything has to work, all the parts have to work for the mission to be successful and it was the first time that I was interacting with a multi-disciplinary team of aerospace engineers, electrical/mechanical engineers, pilots, mission specialists. I was exposed to public affairs and outreach, you name it, it was fascinating. Also, at the time I was primarily hired to assist Kimberly with the major reviews that SOFIA was going to go through, and it was such a good opportunity to get to learn about many other interesting aspects of NASA. And when I got the opportunity to apply for civil service, I was very excited and ready to pursue it. Working with Kimberly on SOFIA – that process – made me realize that I was really into enabling scientific research and serving the community – deep down I love research, but my calling was to really serve the community. There is nothing like it. I really enjoyed it, serving the team and serving the community. Those are the aspects I thought I was very good at, and this position on SOFIA really gave me the opportunity to realize that about myself. It was August of 2018 when I got the civil service position and then things moved really fast. Kimberly transitioned off the project, now it’s January 2019, and I was appointed acting deputy project scientist by the Code S and then within six months I was appointed the acting project scientist, and in March 2020 I was permanently appointed the NASA project scientist for the SOFIA mission.

And congratulations on that! You’ve talked about your scientific direction and specifically things that a layman like me doesn’t understand as fully as probably I should, but this business of submillimeter infrared astronomy and so forth could you take just a quick moment and explain to the general public that underwrites and pays for the research being done, why it’s so important that they should be paying for it through their taxes?

To address any major question in astrophysics, such as how do galaxies form, and how they evolve, how do stars form and how do planets form, how life bearing molecules form in the universe and how are they delivered to planets like Earth, to answer all these questions requires multi-wavelength observations/data. The mid-infrared and far-infrared wavelengths are very difficult to access from the ground because the atmosphere and the water vapor in the earth’s atmosphere blocks all of those wavelengths coming from the universe that we want to study. The two options are: go into space or do airborne operations. Now airborne observations from platforms such as SOFIA still would have some limitations, but it allows us to get above 99.9% of the earth’s water vapor and allows access to the far-infrared universe. There are parts of the Infrared and submillimeter that you can do from the ground like ALMA is doing from a high plateau in Chile, which allows them to access a major portion of submillimeter wavelengths. Herschel allowed us access to wavelength to study molecules that were never seen before, never detected before – molecules that didn’t have transitions at other wavelengths. And these molecular lines allow us to trace the physical conditions and chemistry near where stars are forming in cocoons of dust and gas. Observations at longer IR wavelengths allows us to see through these dusty regions in the interstellar medium. Astronomers have found that in fact half of the radiant energy in the universe is emitted at longer infrared wavelengths. If you’re only studying the Universe in the optical you’re only studying half of the universe!

Oh yes, I remember one of my favorite National Geographic programs was called “The Invisible World” and had to do with things we can’t see because of our human limitations, because either they happen too fast or too slow or in light conditions beyond our visual spectrum. How insects can see things in flowers that we can’t see and that leads them to do what they need to do to pollinate them.

We are actually quite limited, so using these instruments and vehicles and capabilities, expands our ability to explore the universe and try to understand ourselves and the universe in which we live. And you mentioned the identification of molecules with the potential for life and how they are formed and delivered to planets. Almost all of the research that gets done at NASA really, if you follow it and track it back far enough, gets ultimately to the question: what is life, where is it, how can we find it, how can we validated it, and so forth. That’s about the most exciting research that a person can be involved in, so you’re lucky to have landed up here!

Oh, thank you. I think that part of the reason for what I’m doing with SOFIA, I’d just like to say a little bit, and it’s on the SOFIA website too, is that I am doing a survey with SOFIA called the Molecular Line Survey of the Orion IRC2 Hot Core.

What is a hot core? It is a stage before a big massive star forms. It’s a hot dense region in the stellar medium, it’s a protostar, that will result in a big star, a massive star. When this hot, dense gas region turns on, that’s when the molecules start forming and I with my postdoc and interns are studying the chemical composition in the vicinity of these hot cores using SOFIA in the mid-infrared. SOFIA is currently the only facility that provides very high spectral resolution observations at these wavelengths that were not available from previous space based missions. We are doing an unbiased line survey between 5 µm and 28 µm. This survey with SOFIA covers the entire mid-IR region in high spectral resolution. My group is analyzing all the line features associated with atoms and molecules, working on identifying new molecular transitions and even new molecules! We are cataloging everything we see in this wavelength region and building a mid-IR inventory to eventually combine with submillimeter data from Herschel and ALMA to get a more complete picture of the astrochemistry in regions around massive stars where molecules essential for life are forming. These data are also very useful and helpful to laboratory astrophysics scientists. Building as complete a chemical inventory as possible around a protostar is a step towards understanding the chemical processes that are responsible for converting simple molecules into bigger molecules, into life bearing molecules, and into DNA and our amino acids that are key to the formation of life on earth.

How often do you fly on SOFIA?

I love flying on SOFIA. I don’t fly as often as I would like to because my attention is also needed at the SOFIA science center based at Ames. I am also responsible for reporting to the Center and to Headquarters and communicating with our German partners. This part of my job is something I also really enjoy. But I take the opportunity whenever I can to fly on SOFIA. My most memorable time on SOFIA is by far in New Zealand in the summer of 2019, during SOFIA’s southern hemisphere deployment. I flew a lot during that visit. I even did the full “cycle” when I would wake up very early in the morning, like 3 am, to receive SOFIA and to see that side of the story, how operations work when the aircraft/observatory lands. I shadow the operations/mission manager once SOFIA lands… we talk to the pilots and ask if there were any issues, and we talk to the science team working the instrument system…then attend the operations tag to see how they work to resolve the issues to get ready for the next flight and then I go take a nap and then I fly that night, so I did the full cycle! Twice! And that was just fascinating. I was very impressed with every single member of the SOFIA team and their drive to make the next flight possible on time….how every aspect of SOFIA worked in conjunction. I have flown on SOFIA more than 15 times and I have flown both to understand the operations and how things work and also for my research as an observer.

On a lighter note, we like to ask what a typical day is like for you, and what you like best and least about your job.

I don’t think there’s anything like a typical day on a mission like SOFIA (laughs). As the Project Scientist my day is filled with meetings, mostly mission related, but I also do a lot of outreach both to the public and to the science community. I really enjoy that part of my job. The type of meetings I organize on a regular basis are more strategic in nature where I have the science leadership together and we are doing strategic planning for the mission. I have meetings with the project manager to see that things are running smoothly and that the scientific vision is being realized. I have regular meetings with Ames and HQ management to keep them informed and also provide scientific advocacy for SOFIA. I also try my very best to have a lunch break with the staff scientists where we get to just talk about science and other fun stuff that they do on SOFIA that I would not otherwise know. This also allows me to get to know the team. SOFIA is a fairly large project with more than 150 people, so spending quality time with the staff allows me to better appreciate what they do for the mission and how I can help them.

And what you like best and least about your job? And is there a favorite memory about your career or is there some unexpected research finding or a high point that you’ve been a witness to or been involved in?

Sure. I’ll tell you the best thing about my job is the team. I work with an exceptional staff across the board, all the way from the science center to the aircraft operations. I learn from them every single day. And the second best part is just having the challenge and opportunity to always think of ways of how I can continue to improve the observatory’s capabilities, increase the astrophysics community’s involvement with SOFIA, and enhance the scientific output. Least favorite part is when some of my days are just filled with meetings and I don’t have the opportunity to have the time to think or take a step back and approach an issue or concern in a different way.

And is there a special memory, perhaps when you were in New Zealand, or something that you look back on very pleasantly, in your career?

I think scientifically, my first memory of being just wowed, was when I saw the first Herschel spectrum of a galaxy, like Arp 220. It was as if the universe was telling us “Here’s all the things that you have and you didn’t even know about, all of these molecular transitions”. On the project I would say, on SOFIA, my fondest memories are of the New Zealand deployment and really getting to know the team and being part of the SOFIA family and also seeing the data come in and being able to observe that in real time.

So, switching a little bit of gear here, you have a very busy career obviously from what you’ve been describing, but what do you do for fun?

Well, I have two little kids so that keeps us very busy. We have a lot of fun with them. What my husband and I really like are outdoor activities, like hiking. When we were in Boulder, we did a lot of hiking and mountaineering. We even traveled to Ladakh (Tibetan part of India), where we trekked for seven days. It’s a little less now, with kids, but we’re getting them into hiking and other outdoor activities. I love traveling and my family loves it too. Both around the world and within the US. We have traveled quite a bit even with little kids mostly to Asia. Just last winter in 2019-2020 we were in Singapore and India and it was just before COVID-19 hit.

It’s a great thing to do for sure, and especially good for kids. Are your kids young, grade school age or high school age?

My younger one just turned four years old and my older one is eight years old so she’s in third grade right now.

And do you have any pets?

Yes, we have cats! I love cats!

What advice would you give a young person who would like to have the kind of career that you’ve been having either at NASA or anywhere in terms of, well you figured out very young what you wanted to pursue and you pursued it with a very focused and energetic drive within you, but if someone said “I’d like to do what you do”, what kind of advice would you give to them for preparation? Or does it just have to come from within, if it’s not in them then it’s just not?

If you are really interested and passionate about pursuing something, definitely give it a shot because you never know. Continue to dream big. And also, as you’re pursuing something that you think you’d like… during that process/journey you will encounter so many other things, people who are doing different things, other subjects of interest, and you realize “you know what? That’s what I really like!” And for me it started with one thing, it started with astrophysics, but that didn’t mean it had to end up there, it’s just what inspires you to get interested to get curious in understanding things, understanding science, being part of STEM. My brother was always inspired by astrophysics and ended up being a climate scientist. Your curiosity and interest will get you started and motivated and will guide you to where you want to go and what you want to be. Get informed…seek out the right people to talk to…there will be impediments in front of you, but you will find a way to get over them. Stay true to yourself, never give up pursuing your dreams and inspire others.

Who or what inspires you?

It’s such a good question. I think scientifically for me from a very young age when I was fascinated by Einstein and his work, I mean who is not? Richard Feynman and Marie Curie as well….. Outside the scientific world I was inspired by Gandhi… on a different level, right? Of how to be, what kind of person I want to be, and both types of inspiration have to go hand-in-hand, to really become a leader…to make a difference. And I’m also very inspired by people around me, my father specifically. He inspired me every day because not only he is the kindest and the most generous person I have known…he is also a very progressive thinker and he never said the word ‘no’. When it came to me and my life/career…he never said no to trying out things…even when I was fearful of failure he (and my mom) provided a different perspective that helped me get through some difficult times….and I want to strive to be like him.

That is a beautiful sentiment and I hope and expect that eventually he will read this interview and be proud and pleased that you feel that way.

Oh thank you and I will be sure to send it to him.

Thank you for spending this time with us.

Thank you so much for your time in doing this.

Interview performed by Fred and Sara on April 20, 2020

*The Herschel Space Observatory was built and operated by the European Space Agency (ESA). It was active from 2009 to 2013 and was the largest infrared telescope ever launched, carrying a 3.5-meter (11.5 ft) mirror and instruments sensitive to the far infrared and submillimetre wavebands (55–672 µm).

**Located high on the Chajnantor plateau in the Chilean Andes, ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) is a state-of-the-art telescope operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO), together with its international partners, to study light from some of the coldest objects in the Universe. This light has wavelengths of around a millimeter, between infrared light and radio waves, and is therefore known as millimeter and submillimeter radiation. ALMA comprises 66 high-precision antennas, spread over distances of up to 16 kilometers. This global collaboration is the largest ground-based astronomical project in existence.