We usually start with your childhood, where are you from?

Probably like some other scientists, I was a total space cadet since I was a kid. I remember my very first science fair experiment, I was like 6 years old, in first grade, and it was about planetary science, about the rocks and minerals on the Moon and Mars and it just sort of kind of went from there.

Who chose that topic? I think it must have been me.

I was wondering if it was a sign in the first grade and that became… No, it was the thing I wanted to study for my annual science fair.

Then my family moved out to the Bay Area during the dotcom boom. I grew up really close to Ames, I went to Space Camp here when I was eleven. I went to high school in Mountain View and got an internship here when I was sixteen so I have been working here for a pretty long time.

But you weren’t born here?

No, I was born in Chicago but I was pretty happy to come out here and enjoy infinite summer. I love California. I love Chicago too. It’s nice to go visit there, but also nice to come back.

Was there anything in your childhood that pointed you toward being interested in rocks and minerals or toward space?

Yes, I’ve always loved space, I’ve always loved geology, and any time I would have the opportunity to look at the stars, I had a little telescope, I would go and do that. I always felt a connection to this part of science. It drove much of my childhood, I think in sixth grade I read every astronomy textbook in the library, at the little elementary school library. My parents kind of thought it was a phase but it never ended.

Kind of surprising how common it is for someone to have been attracted to specific science areas very early in life. I think it’s true, I think you don’t just fall into this field.

It’s some kind of innate interest that helps you choose what things you are interested in to read or do a science experiment. It wasn’t common in your home?

No, my dad worked in the business world and my mom was staying home when I was a kid. So, it kind of came out of nowhere.

What is your educational background?

I went to Saint Francis High School in Mountain View, that was a good experience. It was nice to be so close to NASA, I would go to school during the day, and at 2 o’clock I’d drive over in my little Toyota to Ames and I worked with Jen Heldmann. She is wonderful, she was one of my first mentors and we got along great. She gave me all this data to analyze and I spent my afternoons, you know, on Mars! That was a pretty cool experience, really formative. It’s funny, a lot of the things she taught me when I was in high school, I still come back to many of those concepts. And it’s interesting now, since I finished my Ph.D. last year, looking back at the evolution of my thinking, and things that I was interested in, a lot of those seeds were planted by Jen, so I can blame her for everything! We’ve actually just started working on a project this year, we went to Iceland together to study these features that are analogous to Martian gullies, and it felt full circle. This is where I started out and now after all these years of studies coming back to these ideas and working with Jen again was really fun.

When you got to the point in your education when you could make some choices about majors and things like that, you showed interest in these things and chose science for your bachelor’s and your Ph.D.?

Yes, when I was a kid I read a lot of Carl Sagan’s books (such a nerd J), he was a professor at Cornell, so that was the only place I wanted to go, and that’s where I went for my bachelors, and little did I know that the sun never comes out there! It was really a hard place to go to school. I wasn’t really prepared for how competitive it was going to be, and how many smart people were there. I mean, high school is not easy but I didn’t really know what I was getting into, but it was such an amazing place because it had every type of study. When I first got there, I started out in astronomy, and I got to go to an observatory in San Diego and do observing and that was really cool. But then I had all these friends who were in geology, and they were getting to go to all these fun places and I said “wait a minute!”, so I actually switched from astronomy to geology in my sophomore year, but I still had a focus on planetary science. Having access to many different things helped me find out what I liked. I was involved in a lot of external research while I was there. I did astronomy, I got into some geology projects, and I did my own undergrad thesis in astrobiology, even got a paper published! Then in the summers, I’d come back out here so that was kind of a nice balance. I think school was really hard but knowing and seeing people on the other side of it helped give me the motivation, the clarity of seeing what’s on the other side of it.

I was about to ask you if you maintained your connection with NASA while at school?

Yeah, I did. I worked with Darlene Lim for the first two years so I got to go to Pavilion Lake, and I worked at Johnson Center for a summer which was really fun and had a lot of different experiences within NASA.

I have to ask you since you mentioned JSC, did you get to work on moon rocks?

I didn’t, but I worked with astronauts and that was a pretty wild experience.

And then your Ph.D.?

Yes, I graduated a semester early and decided I couldn’t take any more winters in New York. I came back here for 8 months and I traveled, worked for a little bit, and decided to go south for the Ph.D. I went to Georgia Tech. Actually, I followed James Wray, who at the time was a postdoc of my advisor at Cornell, Steve Squyres, who was the PI of the Mars Rovers, who had just got a professorship at Georgia Tech. I met him before and he made a really good case for why I should go there. It was a super young program with lots of energy. I remember I was down in the Mojave doing some fieldwork, trying to figure out where I wanted to go. It was one of those trips with a bunch of students, and Chris McKay was there, and I remember sitting one night with him in the cafeteria and he was like “you know, you are a management problem, you should go to a place where people are going to let you decide what you want to work on”. I think that was one of the reasons I chose Georgia Tech, I could have a degree of flexibility in driving my own research, I went there in 2012 and started doing work on remote sensing of Mars. Then I realized that I didn’t know if that was what I really wanted to do so I made this turn into a different field called organic biogeochemistry after spending a year reading papers and reflecting on my academic interests. This field deals with trying to understand the preservation and degradation of the markers of life in the fossil record, and merged all of my interests into one: planetary science, biology, geology, planetary sciences, all stuck together. I came up with my own project idea, I contacted some folks here and a year later I was in the Atacama, so that was pretty cool.

You were one of the best-connected young researchers even before you got here!

I don’t know, I guess I just got really lucky. My first mentors really empowered me. I think if you have good ideas, generally people are really open to that, they open themselves up to helping you, to help shape your career, but yeah, I kind of hit the jackpot pretty early!

And then you did a postdoc?

No, I didn’t. Actually, when Bob Haberle was branch chief of SST, that winter I was doing fieldwork in Utah with some other friends of mine that were about the same age, they were working at Goddard and Johnson, and they told me about this program called Pathways. It was called something else back then, the Co-op program, they were telling me how they had become civil servants, how they were interning and working during the summers and going to school, and I said, “Well I’m kind of already doing that, let me ask Bob about it”. I remember coming back in January and asking Bob, “Hey, have you heard about this program?” And he said “Nope, but let’s make it happen”. I got hired that spring, and I think I was still a teenager when they hired me as a civil servant. It was kind of funny, Bob joked that I lowered the average age by like 30 years!

But that program was instrumental for giving me the support to pursue my own interests and my own Ph.D. work. I went through that program and when I finished school, I converted from a temporary appointment to a permanent position, so I sort of skipped the postdoc stage, which has been a challenge but also a good thing, because I think the training wheels came off right away. Last year when I finished the Ph.D., I just jumped right in, I didn’t take a break. I wrote 18 proposals in one year, which is a lot, and even though I had great mentors and support, it was on me to prove that I could do it. And it’s been a pretty successful year, I got 5 or 6 through! Now that’s a different problem to have. It’s been really fun. This last summer I had my first interns, it’s kind of weird that I’m at that point when I’m transitioning from other people helping me to me helping other people, and that’s a really cool place to be.

Tell us about the work you’ve been doing since you got here.

My research is mostly focused on understanding the preservation of biomarkers in Mars analog environments, and my dissertation work was mostly in the Atacama Desert. We went down there and we were looking at these ancient deposits, millions of years old, and detecting all the biomarkers still present, trying to understand how they degrade, how they get preserved, how they interact with the rocks, and then start to make some postulations about how this might apply to the search for life on Mars. That was the first big paper that I put out.

The Atacama is a really bizarre place, it only rains once every decade in some regions. Things are changing a lot but it’s still super, super dry. I can count the number of plants I saw on those trips on one hand, which is pretty wild. And because it’s so dry there’s no plants, there’s no animals, there’s not really anything colonizing the rocks, and we started asking the question: is anything even living in the soil? The second paper that I wrote was trying to look at how the soil organism changed over this rainfall gradient, where it goes from raining once a year to raining once a decade. The shocking thing is that we didn’t find much evidence for activity of microorganisms in the driest parts of the desert, which is amazing. I’m probably the only pessimistic astrobiologist (laughs) but I think it’s good to start to set bounds on understanding the tolerance of organisms on Earth to dryness because when things get too dry chemistry stops, and when chemistry stops you can’t be alive anymore. I think it’s one of the biggest barriers to survival and I think that study is really helping us understand, and shape our predictions for how much and what type of organisms we would expect to see on Mars.

Have you done any work with finding minerals on Mars with David Blake’s Chemin instrument?

I didn’t, but I did work at Goddard for a year during grad school with the SAM team. I got to work with the Mars Science Laboratory team and I got to help out analyzing data coming down from Mars, that was a really amazing experience, and I am continuing these collaborations now, I’m part of a mission team with some of those folks, they are part of my proposals.

For the benefit of those who may come across this on our website who are not NASA people and who are helping to fund this work as taxpayers, how does the work you are doing support the NASA mission and basically humanity’s imperative to explore?

My work pertains primarily to the search for life, understanding how we might find life on other planets in the Solar System. And part of my work is also to use that information to design and develop new life-detection instruments, something I only recently started doing. Actually, last week we just finished assembling the first prototype of one of the instruments that I hope to build someday. But I think part of my job is also to study Earth, I’ve been in the Atacama, I’ve done work in Antarctica, and right now we are at this point in time where the climate is changing pretty rapidly. In dry environments, it’s interesting to see how the environment is rapidly changing and measure the response of the organisms in the ecosystems to those changes.

Is there such a thing as a typical day for you?

I think I’m lucky because my work is so varied. I spent about a third of the year in the lab, extracting samples, manipulating them, analyzing them, trying to understand them, and that’s pretty fun, the lab is my little oasis. I spent about a third of my time writing, maybe more specifically, with proposals, papers. No one ever told me that when you become a scientist you are really becoming a writer. It’s so important to communicate your findings and explain them in a way that people can understand, so a lot of my job is writing. And my favorite part of the job is the third that I spend in the field. I get to go to all these crazy places, two years ago there was a stretch of time, five months, where I was on five different continents! It’s a cool experience, getting to go and explore these places that very few people get the opportunity to go to. There are places in Antarctica I’ve walked where probably no human being has ever walked before. That feeling is completely surreal, and also sublime. I think that probably is my favorite part of the job. I spent two months in Antarctica and I was part of this team of ten people, I was the only woman, I was the youngest person, and I slept in a tent for two months, with no showers, I didn’t eat anything fresh, and it might sound like this was a very extreme terrible thing, but in reality it was really freeing, like you open your tent in the morning, you look out and you say “OMG where in the world am I?” It’s beautiful, the view of the mountains, the snow, the glaciers, feeling the connection to nature and knowing that your job is to understand it, what a cool thing, you know?

What is your most favorite and least favorite part of your job? You’ve already said that field work is your favorite, so what’s your least favorite?

I don’t mind the writing; I like the creative juices that flow. It’s really important to scientists to spend the time designing the experiment, coming up with the ideas and making sure that they are sound, before you pursue the experiments, because if you don’t do that, that foundational work, the rest of it really doesn’t matter because you are not going to be able to interpret your results and place them in the context with other results. I think that’s where the relevance comes in the long term. I like the writing part. I go to the Mountain View library, I have my little cubicle, it’s quiet and I have my headphones on, got my coffee or my tea and work, I like that part too, I think I’m lucky. If I hate my job, it’s only one or two days a year.

And the least favorite part to your job? It doesn’t sound like that’s it.

No. I think it’s good. NASA Ames is such an amazing place to work. I’ve worked in a lot of NASA centers and they are all great, but this one is where everyone is so friendly and collaborative, there is this amazing spirit of sharing here.

Outside of Ames, I don’t know, but that is a common perspective that many people here share.

Your career is fairly young. Has there been a high point or a favorite memory or research finding so far?

I love the fact that discovery is my favorite part of science, honestly. When I’m in the lab and it’s 9 o’clock at night and I’m getting the first results back from something, that feeling of finding something and knowing that you are the only person that knows it right now, that’s the coolest feeling to me. It’s definitely not the sexy part of my work.

That is at least the third time we have heard that (laughs) That’s funny!

It’s part of the science persona it seems, that you love discovery. And I think that’s why we work at NASA.

Sounds like this is your dream job, but if you didn’t have this job is there another job that you could call your dream job?

I don’t have a backup plan, maybe I’ll become a librarian, or a really moody barista if this falls through! (laughs) But what I see moving forward is getting more into mission work and developing instruments, maybe leading some of those efforts. It’s weird being in school for many years, and then you get out and there is no more goal, and part of what I have done in the last six months to a year is a lot of soul searching, trying to figure out what I see myself doing for the next 5, 10 and 20 years, because I look around and people will spend their entire careers here and it’s been challenging trying to think more long term. I think that’s the trajectory I would like to go on. I don’t want to stop being in the lab, I love doing the science part of it, I think that’s the beauty of it, is the variety in getting information from all the different ends and pulling it together to kind of put together new things.

What advice would you offer to someone younger who wants a career like yours?

I never know how to answer this question. I think it’s a cliché but it’s just all about finding what you are passionate about and pursuing that without stopping, thinking hard that you can achieve those things if you work towards them.

Any hobbies, interesting things you do or what you do for fun?

I’m coming to learn now that I’m getting a little older that having balance in your life is really important. If you don’t find balance it’s really hard to perform at a high level here, because I think we love our jobs so much that we take them home with us, maybe too much. We just had this really long shutdown and you get this surreal feeling that you can’t work, you can’t even check your email, and trying to see who you are outside of all of that, I think that’s a goal of mine to find more balance. But I do have a lot of outside interests. I studied dance at college, I danced for many years and I still dance now. I also enjoy painting and I love reading: I spend too much time in the library!

What kind of dance? Modern dance, like super weird 1960’s New York City dance, but I love ballet too. I love the arts, I think there is a lot of beauty in that. I think the things you find peace or you find balance in are those external things. Having that mindset and bringing it to work is really important because it helps ground you, and center you, and helps you focus and achieve more that if you didn’t.

And you read mostly science books? I don’t read any science books! (laughs). I’m maybe one of the rare people here that doesn’t really like science fiction. Recently I’ve been getting into Russian novelists, and I like poetry.

Are you a sports fan at all? I am.

I saw 3 pictures of you with a Cubs t-shirt on! That’s my favorite field shirt! Chicago roots! Definitely a sports fan. My sister and I, we play in a volleyball league. My youngest sister, she’s a pole vaulter, so sports has always been a big part of our family. I wore a Warriors hat every day for two months in Antarctica because you have to represent your team. The penguins are really competitive (laughs)

You still live very close to where you grew up, do your parents still live around here?

Yes, they live across the bay. It’s really nice to have them so close and I live 3 minutes from work, you can’t beat that commute.

Do you bike? Nope, because I’m always late! Plus, it kind of scares me, and also my bike recently got stolen.

Next summer there’s a new science building opening up and it’s a little bit closer to the front gate, so maybe I’ll starting walking to work! The new collaborative biosciences building is opening up in July, you had to apply to get in. I was one of the PI’s chosen. It’s beautiful, we are going to have big windows, and instead of these concrete separated labs spaces, it’s going to be one big facility. The amazing thing is that everyone else who applied and got into the building, I love all of them, they are amazing scientists and we have a lot in common. I haven’t worked with all of them yet but we have a lot of common threads in our research, so I can see how we might overlap or work together in the future, but it seems like this is the first new laboratory facility since the early 1960s. I’m so happy it’s going to happen. I timed it pretty well, I finished school and boom a new building is coming up! I think that’s where the new generation of experiments are going to find new collaborative niches. I think there is a lot of interesting things to know in the intersection points of these fields. These people have totally different backgrounds than me and we will find a lot of interesting things to work on at those intersection points.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that is not science related?

I don’t know. Finishing college?

You are young enough that you can be excused for not having a big accomplishment just yet because you’ve been pretty immersed in what you do.

Who or what inspires you?

Probably my mentors here really have inspired me throughout my life. Jen Heldmann was a huge inspiration to me and Max Bernstein. They were instrumental in helping me start my career, I’m still friends with them and they still guide me now. I think just seeing them and their happiness in their lives has been really inspirational. Another person that I worked a lot with is Linda Jahnke. She started here in the 1960s, she’s seen it all, I try to learn as much as I can from her because she’s brilliant, she doesn’t take any crap from anyone, and she really has a very good attitude and perspective about everything. She can see the ebb and flow of things, and never gets caught up in the bad feelings, she’s always positive, every time I go see her at her office, she’s always smiling, she’s always giving encouragement, and she’s wicked smart, so smart.

That’s really great to have that positive nature after so many years.

I think you have to because, after so many years, there’s a lot of failure in science, constantly being rejected with proposals, papers being turned back, a lot of criticism, you have to develop a thick skin and be able to see through all of that and still love your job. She’s rare.

What’s your favorite space image?

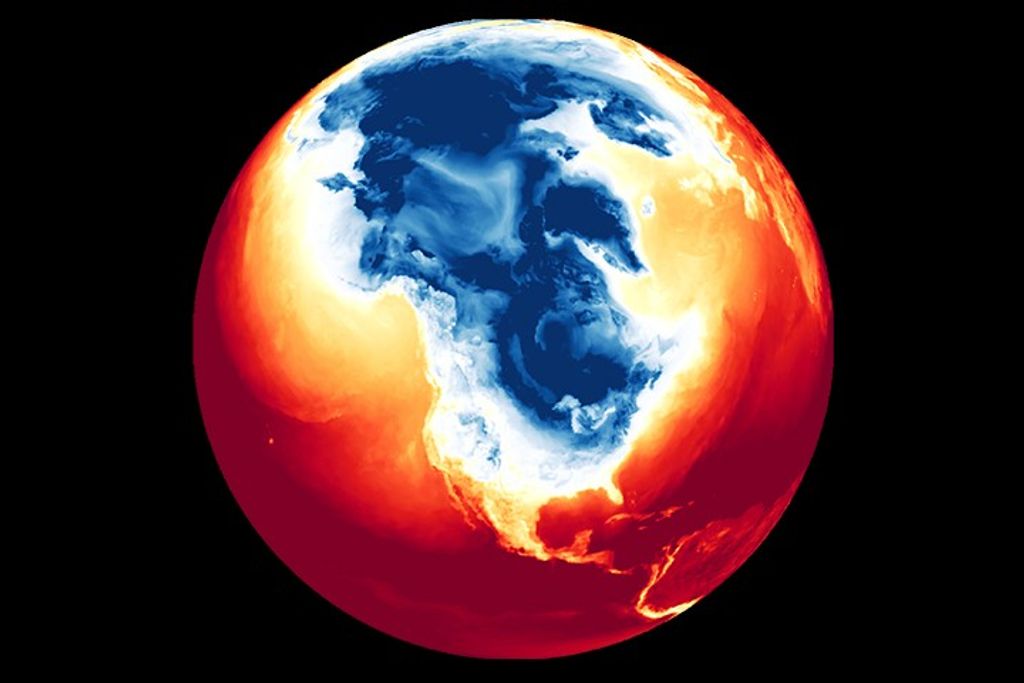

The very first shot from Apollo 8, where you can see the entire Earth in one image, that’s in every textbook in the world, think about that, it’s wild, we have one Earth without borders, consolidated, fragile, and surrounded by nothing,

I believe it was Bill Anders who took that picture. We just celebrated the 50th anniversary of that mission and on one of the TV specials he said he was taking pictures of possible future landing sites on the Moon and he glanced up, it was unplanned, and saw the Earth rising above the horizon of the Moon and he thought it was so spectacular that he took that picture, which became the most famous picture probably ever taken.

Anything else about yourself that we should have asked?

I remember when I revectored in geology, I was on a field trip and remember going to this outcrop and we were looking at these dinosaur bones and at that moment I could imagine how it formed, and what was going on at that time, getting a feeling of how long ago it was, and it was just instantaneous, you have one experience and you immediately know that you were meant to revector in something else.

You mentioned being stimulated by the thrill of discovery.

We are so lucky that we get to work for an agency that allows us to do discovery, I think the impact that we can have on people, even though it’s not necessarily directly practical. Images have power, knowledge has power, we live in an era where information can be spread really rapidly, really widely, being able to take things that are out of reach and bring them into something as clear as an image of the surface of Mars or a distant galaxy, it gets into the global culture.

You also mentioned the uniqueness of Ames as a place to do research and that when you came on board you were instantly treated as a colleague.

Yes, even as a 16-year-old no one treated me as being beneath. That’s weird, incredible, and powerful. Ames is really special for that. We also have such a rich history of exploration here, and a lot of smart people. You get all those people in one place and let them loose, it’s kind of incredible. Ames is definitely the most academic of all the NASA centers but I think that’s one of our strengths, that’s why it makes it special, We might not get to see all the ideas come through but having the space and time to think through them and think about why things are important, why are we doing something, that’s unique.

Thank you so much.

You’re welcome, it was enjoyable.

Interview conducted by Fred van Wert and Sara Rojo on 02/12/2019