Let’s start with your childhood. Where are you from and is there anything about your young years that pointed you toward where you are now?

I was born across the bay in Oakland. My parents were living in Spokane, Washington, when World War II broke out and my dad, at age 30, with a pregnant wife no less, was drafted into the Army. He spent the next 39 months in the Pacific, serving for a time with the allied forces on Guadalcanal. With dad away, mom couldn’t make payments on their house in Spokane, so she moved to Oakland to live with her divorced mother. My brother was almost three years old by the time my dad finally returned from overseas and saw him for the first time. They decided to stay in California and after I was born moved to El Cerrito, where I went to grade school. When I was ten we moved to Auburn, in the Sierra foothills, and they opened up a restaurant along US Highway 40, a major east-west route across the country. After I graduated from Placer High School, I enrolled at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, where, after four years (plus 2½ years of service as a missionary in Holland and Belgium), I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in law enforcement. That came about because I had worked part-time as a campus police officer and thought it would make a good career, plus the university had just established police science as an academic major. I also joined the Air Force ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps), hoping to become a pilot, but learned, to my surprise and dismay, that I didn’t have normal color vision, which was a requirement for pilot candidates. I wasn’t aware of any such deficiency up until then but realized that would probably also affect any potential law enforcement career, so to broaden my educational background, I enrolled in a graduate program in public administration and received the MPA degree in 1972.

How did you get interested in working for NASA?

While serving on active duty at McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento, I took federal and state civil service tests, hoping for a law enforcement or criminal justice-related opportunity that wouldn’t require perfect color vision. When my name bubbled to the top of the list, I got a call from NASA asking me to come to Ames for an interview. I had received inquiries about other jobs but frankly, this one paid $100 a month more, and NASA, of course, has a marvelous brand, so it was an easy choice! The vacancy was for an administrative specialist on a project to bring a new and very large computer system, called the ILLIAC IV, to Ames. This computer had been built with DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) funds at the University of Illinois (the name ILLIAC was derived from Illinois Institute for Advanced Computation), but student unrest related to U.S. involvement in Vietnam caused the Defense Department to seek a more secure location for it. Ames submitted a proposal to house it here and built an extension onto the north side of building N233 for it. That was the beginning of Ames’s role as the supercomputing hub for NASA.

So how long did you work on the ILLIAC Project and then what did you do?

Before coming to work here I wasn’t even aware that NASA had a research center in the Bay Area. Like most people, I thought of NASA as the space agency and mostly heard about the astronauts at Johnson Space Center in Houston and the rockets at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The Apollo moon landing program had ended the year before I arrived but this was still NASA and everything they were doing was interesting. I spent five years with the ILLIAC IV Project, then transferred to a construction engineering project to enlarge and upgrade the 40×80 Foot Subsonic Wind Tunnel by adding a new 80×120 Foot test section and substantially increasing the test section speed. They needed someone to financially manage the more than two dozen work packages involved, and since I had already learned about NASA (direct) and DARPA (reimbursable) funding, I decided it would be a good idea to learn about construction funding as well because different funds have different rules. So I transferred to the engineering group in building N213 and joined the team that was undertaking the wind tunnel rebuild. This wind tunnel, by the way, is the largest structure at Ames, is located just north of the N233A computer lab where the ILLIAC IV was installed, and is notable because the supporting framework is all on the outside of the building. It is a subsonic (low speed) wind tunnel, but don’t be deceived: the 40×80 foot test section delivers 300 knots of airflow, which is more than twice the speed of a category 5 hurricane (there has never been a category 6!).

Anyway, after two years with the wind tunnel project, I saw a vacancy announcement for a “Performance Measurement Analyst” on a project called the Galileo Jupiter Probe. I didn’t know what a performance measurement analyst was but Galileo was a space project and that to me was more like the “real” NASA, so I applied and was selected. I took training to learn about Performance Measurement Systems and the concept of “earned value”, which adds a value of work performed factor to cost and schedule, enabling a more accurate assessment of project status. For this assignment, I traveled monthly to the Hughes Aircraft plant in El Segundo, where the probe was being built and where their system and subsystem managers reported on its progress. In those days two airlines, Pacific Southwest (PSA) and Air Cal, ran frequent shuttles between the Bay Area and Los Angeles and you could show up at the airport with a ticket for either airline and just get on the next plane leaving. They accepted each other’s tickets and you never had to wait more than half an hour. The fare was $17 one way. Times have really changed!

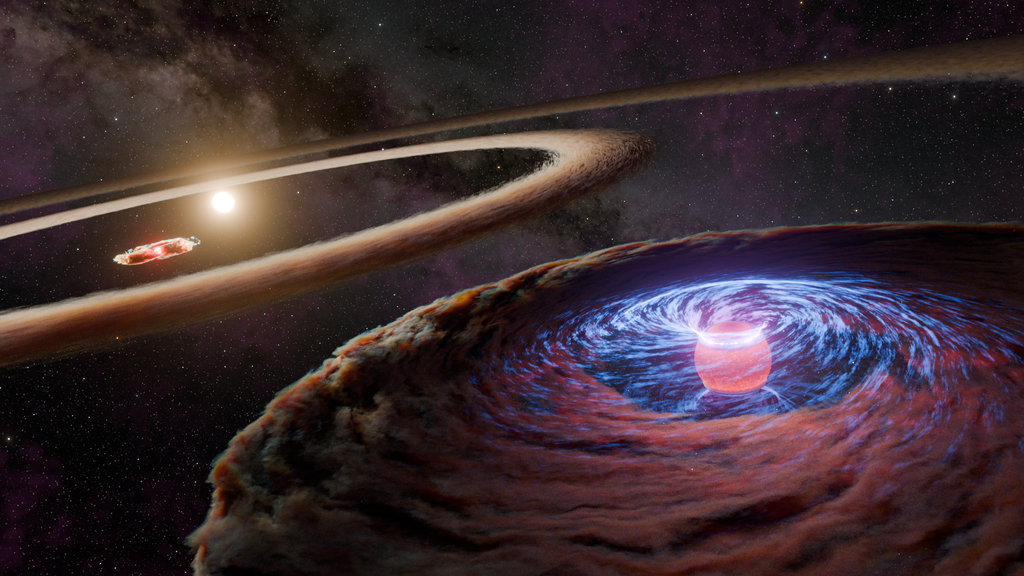

The Galileo Probe from Ames was an instrumented atmospheric entry package attached to the Galileo Orbiter being built by JPL. The plan was for the probe to be carried to Jupiter by the orbiter spacecraft, then to detach five months before encounter and plunge into the Jovian atmosphere, taking measurements and relaying data until it eventually was melted, crushed, and vaporized by the extreme temperatures and immense pressures within the planet, which has no surface on which to land. Entry speed would be 29.7 miles per second, generating temperatures of 15,500 degrees C (28,000 degrees F) for the thermal protection system to deal with. It was by far the most difficult atmospheric entry ever attempted; the probe entered at Mach 50 and had to withstand peak deceleration of 228 g. The probe’s 152 kg heat shield, making up almost half of the probe’s total mass, lost 80 kg during the entry.

It was estimated that the probe might last as long as 45 minutes before being crushed (it actually lasted 57 minutes) and since the data signals would take about that long to arrive at Earth, the whole thing would be over before we knew whether it succeeded or not. Anyway, I found the science fascinating and was glad to be participating in a real NASA space project, at least until fate intervened.

That sounds ominous!

Well, on December 9, 1982, during a test of the newly upgraded 40x80x120 foot wind tunnel, a set of turning vanes just in front of the drive motors and fans tore loose from the wall and was pulled into them, substantially damaging the tunnel and its drive system. Ames scrambled to assemble a repair team and by virtue of my previous work on the project, I was drafted to help and given responsibility for the financial, schedule, and configuration management aspects. The official NASA history of that event is cited as follows:

“Despite an accident during an integrated systems test that caused some damage in 1982, the huge new wind tunnel was dedicated on Dec. 11, 1987.”

Almost glossed over in this entry is the fact that it took over five years to fix the tunnel. That was longer than the original project! So I was transferred back to the construction engineering side of NASA and spent those years supporting the recovery and rebuilding of this enormous aeronautical research facility. Our project team was initially located in building N213. Those familiar with that building may not realize that the large open space area on the second floor was created for our project. It was believed by management at the time that having project personnel in open areas with cubicles, rather than in individual offices, would foster communication, collaboration, and teamwork, so they knocked down the walls of individual offices and created the large L-shaped open space. Nobody, including me, initially wanted to move from their private offices to the open area but I have to admit that it turned out to be fun having everyone nearby and I think it contributed to team cohesiveness, efficiency, and esprit de corps. Anyway, that was a learning opportunity for me because I had no experience with scheduling or configuration management, so I had to take training classes for both. One thing that helped is that the mid-eighties was when computers started becoming available, not desktops yet, but refrigerator size computers, small enough to be located in, say, a copier room. That was the case with our project, where a Digital Equipment Corporation VAX-11/780 minicomputer was installed on the second floor and I found a scheduling program that could run on it. So I got a “dumb terminal” (so called because it didn’t do any computing, merely interfaced with the VAX) on my desk and one Saturday my friend, Herb Finger, and I strung a wire up from my desk into the space above the ceiling panels then across the large open room and down into the copy room where we connected it to the VAX. I was then able to run and print a schedule for the project perhaps once a week at night. I say at night because even a simple program like that was run in batch mode when the computer wasn’t doing anything else and even then it took a couple of hours to run the program. That was very helpful because it would have taken more people than we had available to produce and status an accurate schedule for the project manually.

That assignment lasted five years but was successful in restoring the capability that was lost in the accident and the tunnel, originally built in 1945, is still operating today.

After that project ended, I was asked to join another similar one, this time to rehabilitate the 12-Foot Pressure Tunnel located across the street from the Megabites Café. I opted instead to return to the Space Projects division, which, bless its heart, was willing to take me back after my long sojourn in the aeronautical wilderness! However, by this time the Galileo Probe spacecraft had been completed. In fact, it was at the Cape awaiting launch on the next space shuttle after Challenger 51-L in January of 1986. Well, we all know what happened with that one: the shuttle’s main fuel tank exploded on ascent and launches were stopped for over 2 ½ years while an investigation was conducted and design deficiencies corrected. This was unfortunate for Galileo because it was planned to launch when the planetary positions were optimal for the shortest transit between Earth and Jupiter.

After the Challenger disaster, with the planets no longer in optimal alignment, and with a safety mandated change to a smaller upper stage booster which could not provide the power needed for a direct trajectory, the mission was re-profiled to use several gravitational slingshots, referred to as Venus-Earth-Earth Gravity Assist or VEEGA maneuvers, to provide the additional energy (velocity) required to reach its destination. It was finally launched on October 18, 1989, by Space Shuttle Atlantis on the STS-34 mission and arrived at Jupiter over six years later on December 7, 1995, after gravitational assist flybys of Venus and Earth, and became the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter.

I remember being in the Ames cafeteria when the probe entry took place and I saw Joel Sperans sitting there. Joel was the Probe Project Manager at Ames but had retired during the six years the probe was in transit, so I was glad to see him again. When I told him that, he said, “I almost didn’t come”. I asked him why, knowing how much time and effort he had invested in managing the project for nearly a decade, and he answered: “I didn’t think it would work!” That had to do with the batteries that powered the instruments at encounter, which hadn’t been tested for the length of time they would sit on Earth waiting for launch after the Challenger accident, or the longer time in transit. But Joel was as delighted as everyone else when signals came through confirming that the probe had survived long enough to radio back data on Jupiter’s atmospheric conditions and composition, which was the point of the mission, and even to make some new discoveries which, according to then NASA Associate Administrator for Space Science, Dr. Wesley Huntress, “exceed[ed] all of our most optimistic predictions“.

After Galileo, I was assigned to the Space Projects Division (Code SP), working for division chiefs Skip Nunamaker, Bob Hogan, and Scott Hubbard, as their resources manager and had the good fortune to be associated with several other space projects, including Pioneer Mission Operations, the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF) which became the Spitzer Space Telescope, Superfluid Helium On-Orbit Transfer (SHOOT), the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), and Lunar Prospector.

So you ultimately got back to the space side of NASA.

Yes, every time I made a decision about my career, I tried to head in that direction. And obviously I still think it’s the place to be. When an opportunity arose for a resources management position in the Space Directorate office, I applied for it and I should tell you about my interview for that job. I got a call from David Morrison, the Director of Space Research, who said “I understand you applied for the directorate staff assistant job. I’d like to talk to you about it”. I said, “OK, let me know when it would be convenient to come to your office”. He replied, “Where do you eat lunch?” I said, “Well, I usually eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich right here at my desk”. He said, “Do you mind if I join you?” I said “Of course not” and at 11:30 am he showed up with a burger from McDonald’s, pulled up a chair across from me and we had an engaging conversation about the work our division was doing and what I did to support it, which was primarily resources management. It was the most comfortable job interview I ever had; it didn’t even feel like an interview. He was so genuine and personable, it seemed like we were old friends and I was totally at ease. Anyway, he called later and asked when I thought I could move into building 200, where I would spend the final 18 years of my civil service career.

That was a very interesting and challenging assignment. At the time we had five divisions (Earth Science, Space Science, Life Science, Space Projects and Space Technology), and three projects (SOFIA, Gravitational Biology, and Kepler) with a combined budget over $150M out of a total Ames budget of $530M. We were a very big and scientifically diverse directorate. I got to know a lot about space research outside of just the projects division and, by working in building 200, a lot about what other organizations at Ames were doing as well. This experience broadened in 2007 when I became the Associate Director for Management Operations in the (newly named) Science Directorate. Shortly afterward, at the request of Tim Lee, I undertook administrative responsibility for the NASA Postdoctoral Program (NPP) at Ames and met many bright young people who came here to pursue postdoctoral work.

Can you tell us what Ames was like when you first started and some of the changes that have taken place over the years?

It was very different back then, that’s for sure. First off, until 1995 Moffett Field was an active military base, the Moffett Field Naval Air Station, with many Navy aircraft stationed here. Its primary mission was coastal protection during the cold war and dozens of ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare) patrol planes flew regular missions out of Moffett. When I arrived, the primary aircraft for that was the Lockheed P-3 Orion like the one on static display near the airfield tower today. They flew constantly with sometimes four of them in the pattern at the same time. We lived just across highway 101 and my kids grew up seeing them out the living room window all day long, circling for practice take-offs and landings. NASA also had aircraft based here, including the C-141 Kuiper Airborne Observatory, the predecessor of SOFIA, along with a Convair 990 flying research laboratory named Galileo (not to be confused with the spacecraft), which some of our people may have flown on. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in April 1973 when it was accidentally cleared to land on the same runway as a Navy P-3 and they collided over the golf course across 101 south of Moffett.

A second CV990, named Galileo II, flew research missions for another 12 years until it too was destroyed, this time in a fire while attempting a takeoff at March Air Force Base in July 1985. On the brighter side, the Kuiper flew for many years with its 36-inch telescope until it was decommissioned so the money in that program could be redirected to SOFIA, which would eventually produce a much larger airborne telescope on a Boeing 747-SP platform. Unfortunately, by the time SOFIA became operational NASA had consolidated its aircraft at Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center in Southern California, so we don’t get to see SOFIA here very often. Ames also flew such interesting aircraft as the Tilt Rotor, which, after a long, difficult, and problem-plagued development, became the V-22 Osprey used by the Marines, the British-made Harrier jump jet, and the Lockheed U-2 and ER-2 aircraft, which did Earth mapping. That was an interesting airplane to watch at takeoff. It had very long wings, supported by landing gear at the wingtips, to keep them from touching the ground, that fell away at liftoff. The takeoff roll was very short, about 100 yards, then it tilted up at what seemed like a 45-degree angle and climbed right out of sight. And the NOISE! With a high power turbojet engine and the thrust pointed right down at you, it was EXTREMELY loud. It always took off at 11:00 am or 1:00 pm, depending on the mission, and air traffic control had to clear space all the way up to 50,000 feet before takeoff because it climbed so fast there wasn’t time for incremental clearances as it ascended. For the same reason, the pilot had to breathe pure oxygen (to purge nitrogen from his blood) and wear a pressurized flight suit an hour before takeoff. There was also a Quiet Shorthaul Research Aircraft (QSRA) that had four fanjets attached in front of the wings, to blast air over them, increasing lift and decreasing noise (from below). It was able to take off after a very short roll and fly quite slowly. With an approach speed as low as 60 knots, if it got into a strong headwind, it could seem like it was just hovering in the air. I recall watching it during an airshow demonstration (yes we had air shows at Moffett Field in those days) coming in to land. It seemed to almost come to a stop over highway 101, then pointed the nose downward and drove itself down onto the runway. With a landing roll as short as 300 feet, it is the only four-engine jet capable of both taking off and landing on an aircraft carrier without using the launch or arresting cables, as it did on the USS Kitty Hawk. Perhaps the most unusual aircraft was the AD-1 “scissor wing” (also called “oblique wing”) concept aircraft designed by Ames’ own Robert T. Jones, which featured a straight wing on a pivot that could be perpendicular to the fuselage for maximum low speed control, and then rotated so as to be pointing forward on one side and backward on the other, for maximum aerodynamic efficiency at high speeds. If you love interesting airplanes, as I do, this was the place to be.

Anyway, much of this came to an end when the Navy was ordered to vacate Moffett Field and transfer its assets to other Naval bases as part of the Base Realignment and Closing (BRAC) program in the 1990s. For budget reasons, NASA also transferred its aircraft out of Moffett Field and since then we haven’t seen nearly the number of aviation operations here. But it was fun while it lasted.

I mentioned air shows and should say something about that. Moffett Field held air shows, open to the public, every year until the Navy left in 1995. And every other year, they featured the Blue Angels flight demonstration team. This event attracted upwards of 100,000 people. NASA would often fly some of its unique or unusual research aircraft and a few times hot air balloons operated inside Hangar 1. I recall one time the Air Force brought in a B-52 bomber and NASA brought the Boeing 747 Space Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, and you could walk through them. I talked to the crew chief on the shuttle carrier and asked what kind of mileage it got. He answered that with the space shuttle attached it could not fly above 11,000 feet and burned a gallon of fuel for every length of the airplane it flew! That’s why it had to stop in Houston to refuel on its way from Edwards AFB to the Cape.

How about Ames in the old days?

Well, it’s hard to know where to start. One of the things to remember about the “old days” is that everything was done on paper. We didn’t have computers, and even calculators were expensive and tightly controlled items. If you purchased a desktop calculator, it generally cost from $300-$500 and you had to also buy an attachment cable to secure it to your desk. Financial spreadsheets were handwritten on ledger paper.

Government forms were also all paper, sometimes with carbon copies attached and had to be hand-carried around for signatures. Carbonless paper was a real technological breakthrough! Depending on the items and amount, purchase requests had to be signed by finance, property, safety, procurement, directorate, and sometimes even center management. It could take a week or two to mail one from place to place, so many of them were just hand carried. That could take from an hour to half a day. There was also something called the Imprest Fund, accessed via Form 44, which essentially was for petty cash. If the cost was minimal, you could obtain the requisite signatures and then walk it over to the cashier’s window (yes, there was one) and obtain actual money! But it came with tight strings: you had just 48 hours to return with your receipt and change, otherwise, your branch or division chief was notified and asked to hunt you down.

For ten years ending in 1981, there was also a taxi service at Ames. You could call a number and request a taxi to pick you up, take you across the center, and drop you off. I found it convenient when I had a box of reports that had been printed for me at Reproduction Services in building 241, that I needed to lug back to my office in building 244. Especially if it was raining!

The energy crisis of the mid-’70s into the 80’s also hit Ames employees hard. The price of gasoline rose dramatically and then it became a matter of availability due to shortages. Gasoline itself wasn’t rationed but the opportunity to buy it was. Vehicles with odd-numbered license plates (based on the last digit) could only buy gas on odd-numbered days of the month, and even-numbered plates on even days. This led to long lines at gas stations, as people were afraid to let their tanks drop below half full, and stations sometimes ran out of gas. It was a nightmare for those with long commutes. Ames, as a prodigious consumer of electricity – mostly due to its wind tunnels – implemented a number of measures designed to reduce energy use. For one thing it prompted Ames to lower the temperature of water heaters. But the law of unintended consequences promptly manifested itself when legionella bacteria was found in the now warm hot water lines. After a lot of testing and analysis, water heaters were set back to hot. Stickers were put in restrooms cautioning that the water temperature had been raised. On one such sticker someone wrote “to save energy?” But the real reason was to kill bacteria.

Another action that directly affected employees was a mandate that buildings could not be heated above 68 degrees in the winter nor cooled below 78 degrees in the summer. Thermostats were set to these parameters and then locked down so individuals couldn’t adjust them. This had the entirely predictable effect of proliferating the purchase and use of individual space heaters in offices and under desks. Facilities Services also sent electricians around to remove every third fluorescent light tube in fixtures in offices, labs, restrooms, and hallways. When employees responded by simply buying and replacing them, the technicians returned and actually cut the wires in light fixtures so that the removed light tubes would not work even if replaced. You walked down the halls and every third light fixture was dark. I assumed that was how it would be for the rest of my days, but fortunately, the crisis eventually passed and things are back to normal (?) now.

That was also a time when smoking was allowed in buildings and offices. Some people smoked a lot and the smoke worked its way down the halls and into other peoples’ offices, but that’s just the way it was so you got used to it. But in 1987, largely as a result of medical evidence announced by the U.S. Surgeon General that placed nonsmokers at risk of developing disease from long-term exposure to environmental (passive) tobacco smoke, a policy was implemented to minimize the presence of tobacco smoke at employees workstations by banning smoking in common work areas. However, smoking was still permitted in some indoor areas; i.e., hallways, private offices, lobbies, vending rooms, etc. until 1997, when the President issued an executive order prohibiting smoking in all interior space owned, rented, or leased by the executive branch of the Federal Government, and in any outdoor areas under executive branch control in front of air intake ducts. So that change wasn’t all that long ago.

The big revolution, at least for me, happened around 1985 when the first personal computers started to appear at Ames. I was on the 40x80x120 Wind Tunnel project at the time and I got a desktop system called a PC-AT. It had a black and white screen but you could do spreadsheets using a program called “Symphony” on it and it would do the calculations for you! I felt like I’d died and gone to heaven! Prior to that, I would do the calculations manually, or with the help of a calculator, and then give them to the office secretary, who would type them into a report. The numbers didn’t always align, but the totals were (mostly) correct. Anyway, being able to prepare a report myself and have the calculations done for me was a godsend (google it). But you had to memorize computer commands and keystroke sequences in order for that to happen since the Graphic User Interface (GUI – think mouse and trackpad) pioneered by Apple wasn’t yet widely available. No longer did I have to run reports and schedules overnight, and I could print them myself. Printers in those days were also rudimentary by our standards. They were loud, printed on fanfold paper with perforations where the pages were separated (also noisily), or sometimes on thermal paper, which seemed fine until you looked at them years later when the thermal image had faded to illegibility. Those were the days!

Similar new technology affected conference and meeting rooms. In the ’70s chalkboards were the primary means of visual communications for large groups. The first technological leap was from white chalk on a blackboard to yellow chalk on a green board: easier on the eyes, it was claimed. But the screeching of chalk on boards was commonplace until into the ’90s when whiteboards became available. These were glossy, clean, quiet (although they squeaked a little) and you could write and draw in colors, using a non-permanent marker. That is if you didn’t make the common mistake of grabbing a regular (permanent) marker instead. If that happened your doodlings became immortalized! This was also the time when projectors could display words and pictures from transparencies onto a screen for all to see. Then came improvements so that what was written or typed on an ordinary sheet of paper could be projected onto a screen. This probably seems ancient to anyone who assumes it has always been possible to simply connect a laptop and show anything on it, documents, pictures, the works, to everyone in the room.

I got my first Macintosh computer in 1989 and since then have been primarily a “Mac person”, except when NASA bought financial software that worked best on the PC. Now everything is computerized and if the power goes out, most people just schmooze around in the hallways or find something to read until it comes on again.

The old days also featured a wonderful Children’s Christmas Party (yes, it was called that) held in NASA’s big hangar (N211) featuring Santa Claus’ arrival in a helicopter! Our kids loved it and though I haven’t been to one recently, I don’t believe they are still using the helicopter.

Also, before the theater-like auditorium was built in N201, that area was a flat floor assembly room for large meetings. And prior to that, before the construction of building N235, it was the cafeteria.

Before the Navy left in 1995, it shared some of its facilities with NASA personnel. The present Ames Conference Center (N3) used to be the Officer’s Club and was quite nice as military facilities go. Civil servants of grade GS-9 (equivalent to the 0-1 rank of second lieutenant) or higher were eligible to dine there as they would at any off-base restaurant. I still have a card allowing me access, which I used a couple of times.

What about talents, hobbies, etc.? What do you most like to do in your spare time?

I love to read and have accumulated so many books that my wife calls them firewood and threatens to call the Goodwill truck whenever I’m away from home for very long. I stow them in bookcases and boxes in the garage, in the office room, in closets, under the bed, in my workshop, everywhere. I realize now that I won’t ever be able to read them all and I really should stop buying them: she calls them my “heroin”! My preference leans to historical non-fiction. There are so many true stories that I want to learn about that it seems almost a waste of time to read fiction. Take the Titanic disaster for example. That story is full of so much human drama and emotion that I have read everything I can get my hands on about it, including the records of both the American and British inquiries that followed. So I find it incredible that Hollywood could make a movie about it and ignore one of its most dramatic and heart wrenching aspects, namely the saga of the SS Californian’s proximity to the Titanic and its failure to pursue the meaning of the distress signals, both visual (fireworks-like rockets) and by radio (Morse code), that were being sent out, in order to insert a totally made up love story about two fictitious persons in its place. The Titanic story needed none of that. It was one of the most incredible sea tragedies of all time, and yet the director apparently felt a need to add artificial drama. I just don’t get it. While I’m on the subject, I also think that Captain Smith gets altogether too much credit for heroically choosing to go down with the ship when he was ultimately responsible for letting lifeboats be launched only partially full. That was a real breach of his responsibility, although by his other behavior I presume he was in total shock, and perhaps may be forgiven for such a serious lapse. I also think the ship’s band that played jaunty tunes on the deck during the two hours between hitting the iceberg and sinking, rather than being celebrated for its courage and selflessness, bears some responsibility for contributing to a lack of urgency on the part of passengers who may have thought, “well how serious can this be if the band is playing?”, thus abetting their natural reluctance to climb into a tiny lifeboat at night, in mid ocean. Anyway, sorry for that tangent but that’s how my thinking goes. I like true-life adventures, such as about the Shackleton Expedition (Endurance) , the invention of the airplane (The Wright Brothers) , the Manhatten Project (The Making of the Atomic Bomb), the subsequent trial of the Rosenbergs (The Implosion Conspiracy), the breaking of the enigma code (The Code Breakers of Bletchley Park), and practically any book about survival at sea (Lost, Alone, Adrift). Right now I’m reading “Flags of our Fathers” by James Bradley, the son of one of the flag raisers on Iwo Jima. My father served in the Army on Guadalcanal for a time after the Marines took the island at great cost, and he would never talk about it. So WWII history is always of interest to me.

Other interests?

I wish I had more diligently pursued music lessons when I was a kid. I admire anyone who can play a musical instrument while the most I can do is sing. But that was enough since I met my wife in a high school choir class and we celebrated our 50th anniversary this past summer.

What kind of music do you like?

I guess I’m old fashioned, but hard rock, heavy metal, and rap aren’t my thing. I like 40’s and 50’s pop songs, early rock & roll, ragtime, show tunes, easy listening, etc., although my favorite is a very small niche: organ music. And not just organ, but classical, romantic (in the historical sense) because of its expressiveness and emotional, rather than primarily intellectual, effect on me, particularly although not exclusively the French school. I’m blown away by how a single person can play with precision on multiple manuals, including with their feet, controlling over 10,000 pipes with such a range of sounds, it’s just amazing. Often the pieces are very chromatic and quite complex, with a fugue, for instance, combining multiple melodic lines woven together to create a rich tapestry of sound, it just touches me. Improvisation is a particularly amazing ability at which I can only marvel. One of my favorites is an organist improvising a seven-minute postlude in a French cathedral (St. Sulpice in Paris) following a service. It’s on youtube and just blows me away. (Definitely not your grandmother’s church music!) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2PncS8LcoaI

(She starts playing at 00:47 The audience down in the pews doesn’t hear the voices or the mechanical sounds of keys, couplers, and stops that you hear on the recording.)

What accomplishment are you most proud of that doesn’t involve your work at NASA?

That would have to be my two kids (adults now), Miesha and Jeremy. Despite all my parenting efforts, both have turned into (reasonably) well adjusted, productive adults and good citizens. She has a degree in kinesiology and worked as a Santa Clara County EMT with the Rural-Metro 911 emergency ambulance service, but recently moved to Idaho and is practicing neuromuscular therapeutic massage. His degree is in psychology, with a master of science in counseling, and he is a licensed marriage and family therapist, specializing in juvenile mental health issues. He also has an MBA and is currently VP of residential services and business development with Summitview Child and Family Services. He marched four years with the Santa Clara Vanguard Drum and Bugle Corps, wrote a book about it, and rode his bicycle across America in 2001, posting about the experience each day. I’m very proud of both of them.

What do you do for fun?

I like to camp, bike, swim, listen to music, read, and watch sports. I’m fortunate to live in Sunnyvale and can use the Stevens Creek trail as a bicycle route to work. I’ve been biking fairly consistently for 16 years, racking up over 20,000 miles, but I’m not a fanatic. I don’t bike in the rain (it gets the bike dirty) or, as I told my son, when the overnight temperature is below my age (although that’s not exactly true anymore)! I used to like working on cars until technological advancements made it practically impossible, at least for me. My nickname around the house is “Mr. Badwrench”.

Is there a particular experience from your long career that stands out in your mind?

Yes, when I served on the Ames Exchange Council, Jim Brass and I were talking one day about the airplanes and simulators here at Ames. Kathleen Starmer, another member of the Council, who was connected with the VMS (Vertical Motion Simulator), overheard us. The VMS is a world-class flight simulator with an unsurpassed range of motion and cab (cockpit) flexibility, used by many aerospace programs, including the space shuttle, for engineering studies, design validation, and astronaut training. Anyway, she asked somewhat casually, if we would like to “fly” it. We asked, “Could we do that?” and she said, “Well, they often need to practice operating it, so if you have the time, I could probably schedule you.” DID WE HAVE THE TIME? Was she kidding? So Jim and I each took half-hour spins in it, which consisted of 5 space shuttle landing attempts. Each attempt started at 10,000 feet and ended about 3 minutes later either with wheels on the runway or with the display freezing abruptly when the simulator realized your landing attempt was not going to end well. This is pretty realistic since computers control much of the shuttle’s flight until the last 4-5 minutes anyway. Airliners typically pitch down about 3 degrees when approaching the runway. The space shuttle pitches down 20 degrees and descends initially at about 10,000 feet per minute, so things happen pretty fast. We were told to keep the little triangle inside the circle on the HUD (head-up display) that was projected onto the windscreen. Those icons floated around and moved as the shuttle moved and it was like playing a video game. Anyway, with a little coaching, I got onto the runway on my first attempt, and I thought, “this is a piece of cake!”. The second attempt didn’t go as well, as I got below the glideslope and then overcorrected, chasing the symbols up and down with the controls, which only made things worse. Fortunately, the VMS doesn’t simulate the horrible crash that would have resulted from my amateurish inputs. It merely freezes up and then is recycled back up to 10,000 feet for another try. I made it safely down on my 3rd attempt proving at least that I was capable of a positive learning curve. For my 4th attempt, he said: “let’s try a night landing”. I was brimming with confidence, having, as I imagined, “gotten the hang of it” and I said, rather brashly, “that won’t matter since all I have to do is keep the little triangle inside the circle”. He said, “Trust me, it matters”. And he was right. It’s amazing how much we use our peripheral vision without even being aware of it. So I was now even, at two successes and two failures. For the 5th try, he programmed the landing to be in Spain. “Spain?” I said. Can you even land the space shuttle in Spain? That’s when I learned that the shuttle had numerous alternate landing sites around the world, including in the Azores, Spain, France, the U.K., Germany, Morocco, Diego Garcia, Senegal, Nigeria, and New Mexico, most of them in case of emergency and only one of which was ever actually used. Anyway, I made it safely into Spain, so I was batting .600 at that point and decided to leave well enough alone. But it was a blast and they recorded it all on a DVD, so I have a lasting memory of my 30 minutes of fame!

Who inspires you?

Without a doubt the people I work with. I’ve been so fortunate to have a career at NASA where I support and associate with so many smart and dedicated people. I see what you all accomplish and hope I am helping in a small way. I’m inspired by the example of people who aspire to excellence in whatever field they pursue. I’m surrounded by many scholarly luminaries here at Ames, but it doesn’t have to be in academic or scientific pursuits. As a youngster, I did part of my growing up on a farm and I was amazed at the effort, knowledge, and diligence it takes to do that kind of work and succeed. You have to know a ton of things and you have to work all the time. And even then you won’t get rich. But you will earn a measure of satisfaction that is the equal of others in more highly regarded fields. To me, it doesn’t matter if you are a technical professional, or a waiter, or a soldier, a musician, or a taxi driver, or janitor. Putting in an honest effort with a desire to excel at your job, however seemingly menial, is worthy of respect, admiration, and even inspiration. I had an opportunity to speak at an award ceremony here at Ames a few years ago and I said that I had been on numerous projects and mission teams doing support work and on none of them would I have been remotely considered the most important person on the team. But I had a job to do that was important to the project and I needed to do it to the best of my ability. By analogy, I cited a few failures NASA has experienced along the way, caused by seemingly insignificant parts, such as a rubber O-ring or a piece of foam, that didn’t stay in place and do its job, and how that imperiled that entire mission. We all have a part to play in getting the work of NASA done and we all need to do our best if the thing is to succeed.

What advice would you give to a young aspiring student who wants a career at NASA?

My mom once interviewed for a job for which she had no prior experience. When asked about that she said, “I don’t have any, but I can do anything anybody else can do”. That so impressed the owner that she was hired on the spot. I’ve always admired her “can do” spirit. I’ve also applied for jobs for which I didn’t have experience but I knew I could do, or learn to do, whatever was needed. Doing performance measurement analysis for the Galileo Probe project was one example and it got me into Code S, where I’ve spent the better part of my career at Ames. NASA is a “can do” agency, so people with that attitude tend to do well here.

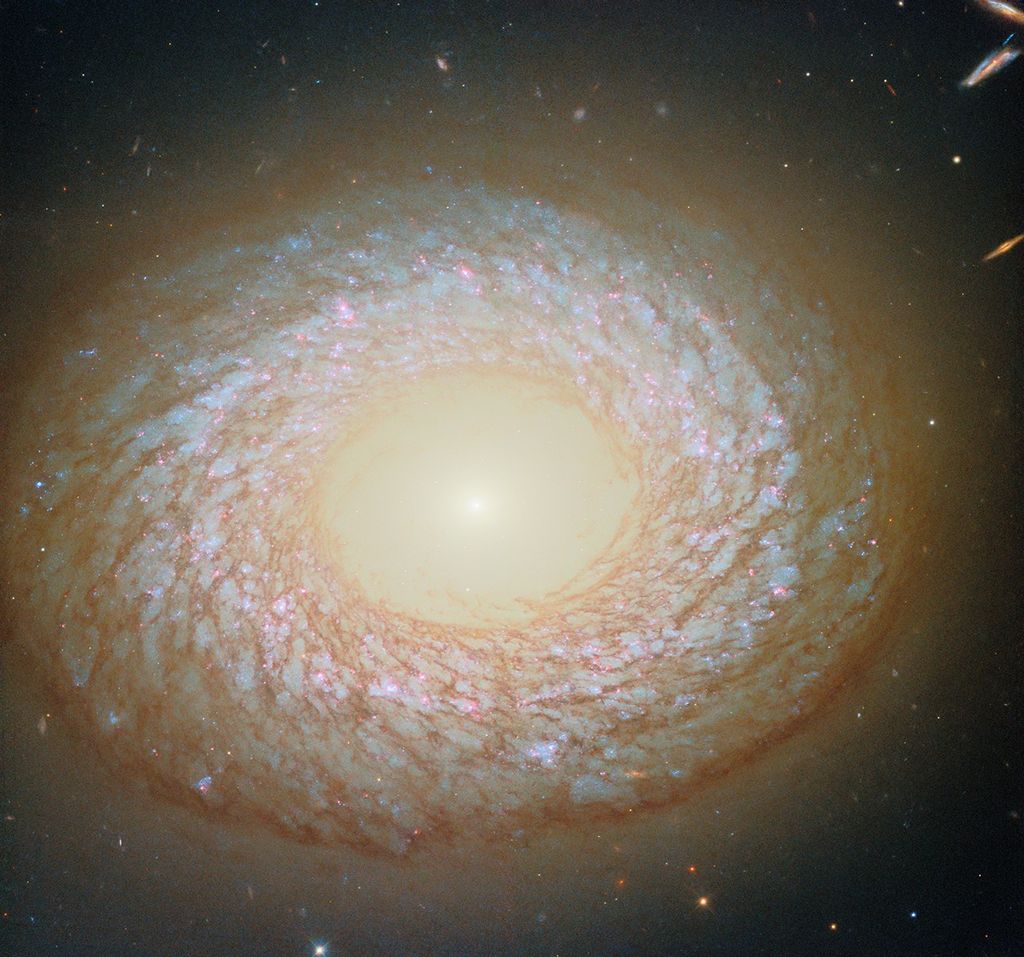

Do you have a favorite space image?

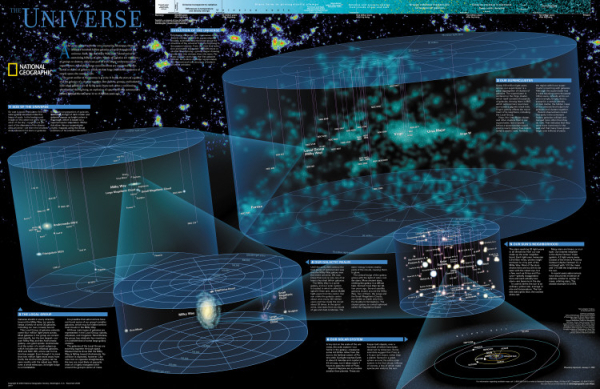

Yes, it is a wall map of the Universe published in the National Geographic magazine several years ago. You see the Earth as part of the solar system and then stepping back you see our solar system as but one of many such stars and systems in the Milky Way galaxy, then stepping back again you see other galaxies in our galactic realm, which are in turn part of our supercluster, and so on and so on, each step showing the staggering immensity of Creation.

How about a favorite quote?

That’s like asking for my favorite color! There are so many. But in the context of space, there is a verse from scripture that says:

“The Earth rolls upon her wings, and the sun giveth his light by day, and the moon giveth her light by night, and the stars also give their light, as they roll upon their wings in their glory, in the midst of the power of God. Unto what shall I liken these kingdoms, that ye may understand? Behold, all these are kingdoms, and any man who hath seen any or the least of these hath seen God moving in his majesty and power.”