Good morning Carol. Let’s start with your young years, where were you born, where you grew up, something about your family at that time, your early schooling and so forth, and if there was anything in those early years that oriented you toward the pursuits that landed you eventually here.

I think my story may not be unique, but some might think of it as unusual, because some people know from their first conscious thought what they wanted to do with their life, and I was one of those people. I grew up in a small town in Utah, Tooele. Actually, I was born in the small town of American Fork where my mother grew up and my grandparents lived. My brother to this day lives in American Fork. According to my mom, I don’t really have memories from this period, when I was a child I always said I was going to be a space scientist. I’m going to Mars! (laughs)

How did you know that?

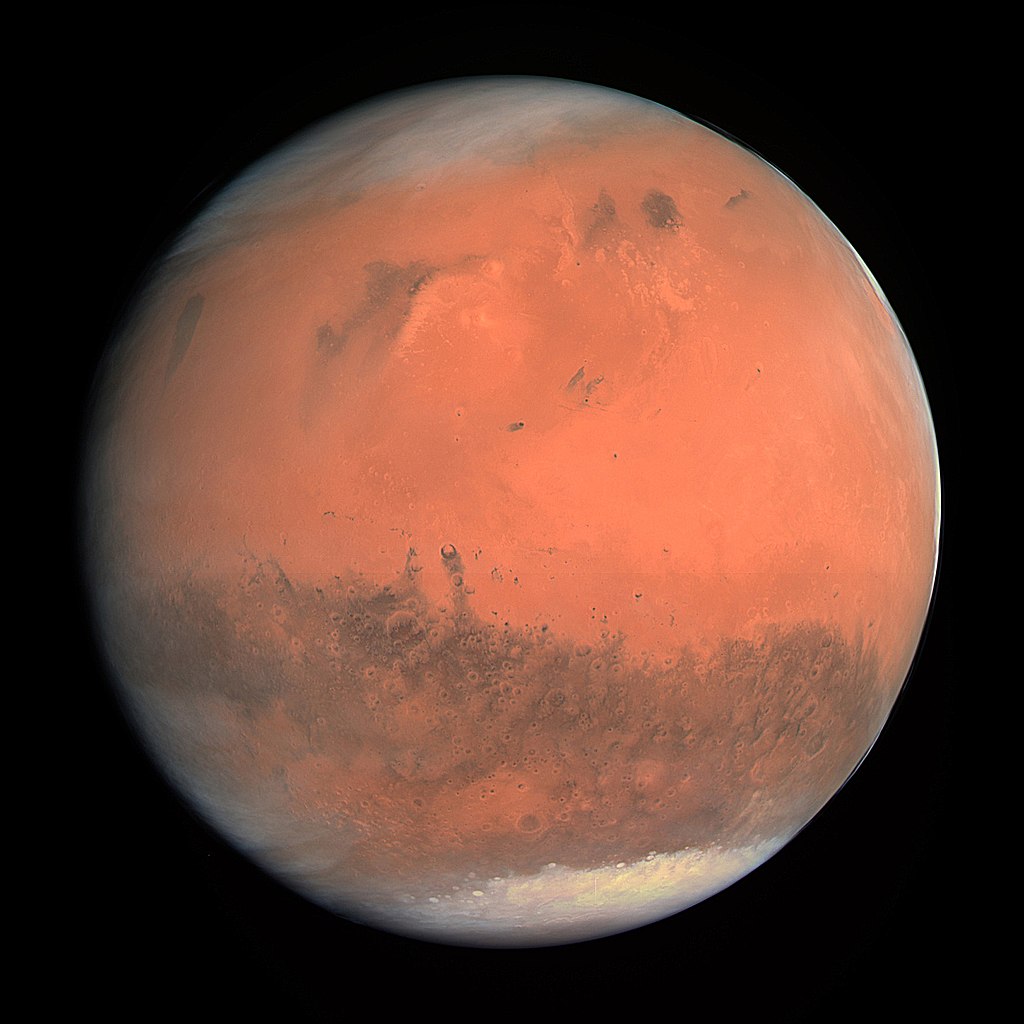

That is the big question. There was not much in my environment to give me that idea. When I was growing up the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs were spinning up and they were on the news every night, they were pretty much THE news, so I think that might have been some kind of an influence, but I think I just knew. Like I say, some people just know their purpose in life right from the start. Then when I was eight, I had this series of dreams where I was on Mars! These dreams were like episodes of a serial, like watching a TV serial, it was night after night for about a week. Actually, I was on a summer vacation staying at my grandparent’s house, and they had this bed in their basement, which was always cold, and I stayed down sleeping in the basement, having these dreams and I was just so engaged in the dreams that I didn’t want to wake up and I didn’t want to do anything else. They kind of forced me to come up for meals and then I just wanted to go back down and go back to sleep. There was a continuity to the dreams, there was a whole storyline. And I was on Mars!

How interesting!

I was on Mars for this entire period, and from that day forward, I just knew that’s what I’m supposed to be doing!

Did you have brothers and sisters?

I had two brothers, an older brother and a younger brother. And they had no similar experience.

Did either of them turn out to be space-minded or science-minded?

No, no.

What did your parents do?

My father was a car dealer and my mom sort of helped with his business and no one in my family had ever gone to college. No one in my personal friend group, when I was in high school, went on to college, some even dropped out of high school.

Well, it must’ve occurred to you at some point that if you were going to be a space scientist that you did have to have a certain level of education. When did you start making choices about that?

I was deeply, deeply interested in science through middle school. And then I got to high school and I got distracted with all the things one gets distracted with in high school, so I kind of forgot about all this until I started college. I went to college at the University of Utah. In high school, I had taken advanced placement physics and chemistry, so it turned out that I didn’t have to take any science at all in college because these actually counted toward your basic general education requirements.

So, this was the opposite of remedial, which is more common today.

Yes, and I had done well enough in these advanced placement classes that I had college credits already in science. I started college as an art major. I had to pick a major, you’re starting school, right? I had taken a year off between high school and college, I had actually come to California, and I had taken some classes at the College of Marin in California, art classes in junior college … glass blowing and jewelry making and that kind of stuff (laughs).

This was during your hippie years?

Well, I suppose you could call it that. That was the era. Anyway, after a year in California, I discovered, because I had always intended to go to the university, that I couldn’t get in-state tuition in California until I was 21, even though I had lived on my own and had jobs for a year, I was not considered eligible for California in-state tuition assistance until I was 21. So, I went back to Utah. And I started in college as an art major but because it was my first year, I took a variety of different things out of interest and finally in my third quarter, I took an astronomy class. The textbook for that class was Carl Sagan’s first book, which was called: “Intelligent Life in the Universe”. I just loved this class and felt I had reawakened my dream so at the end of the class I went to the prof and said “This is it! This is what I want to do for my life, for the rest of my life, this is exactly what I want to do. So, what do I do?” And he said, “Well you’re going to have to take a lot of math”. And in high school I had given up on math, I had not taken even high school algebra. He said, “You need to major in physics, and you need to take a lot of math”. And my reaction was like “PHYSICS! MATH! WHAT?” (laughs). The very next quarter I changed my major to physics, I enrolled in the physics department, and with my ‘Carol going overboard’ approach: I signed up for classes. The Physics department had two programs, they had a kind of engineer’s physics classes, and then they had a special sort of honors physics program for the people that were kind of their pet students that were going to go to graduate school and become physicists. And so I signed up for that class group. Because I was impatient and wanted to jump right in, I was always behind in the math. So, I started the physics that required calculus while I was taking geometry, (laughs) which was a prerequisite for taking calculus! I was always a year behind in the math. But by the time I would get the math class I really understood why I needed it! I managed to get through that program. There were only five or six of us in that program and my classmates were super bright. Anyway, I got a physics degree from the University of Utah and then I started looking around for my path to the profession, realizing it would require graduate school. My last year in my undergraduate program I saw an opportunity posted on the wall and I applied for and got an internship on a field experiment that was actually one of the first major international meteorology field experiments called GATE. An Ames aircraft was one of the aircraft involved in this big field campaign, which included ships and airplanes and instrumentation, and it was all staged out of Dakar, Senegal.

So, there was an Ames component to this field campaign.

Yes. In Senegal, my job was to fly on a Learjet and run the instruments on the airplane, which was so cool! It was fabulous! And, of course, I met all these incredible people, scientists, etc.

Did you meet people from Ames?

No, I didn’t make any connections there. The connections that I made were actually in Colorado, particularly at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), which was one of the scientific institutions that was in the aircraft program and I was flying on an aircraft daily so I became really good friends with those people. Once I was searching around for graduate schools, and I knew that I wanted to do planetary science, but I didn’t know where to go to get a degree in that field. I was in a physics program and the faculty had no way to advise me because they didn’t know anything about it either. So, I just went on the road. I knew of Carl Sagan and I went to Cornell University to look for him, so I could talk to him, you know! Get advice, right? It turns out when I got there, Carl wasn’t there but I talked to other people on the faculty. I also made a trip to Boulder, Colorado, where my friends who worked at NCAR lived, and there was an interdisciplinary program there that had some planetary science and space physics, and I also went to the University of Arizona. I just went to all the places that I had heard did this kind of work. I applied to all of them but finally, I chose to go to Colorado. There I met other graduate students, which included Chris McKay.

Was Chris a grad student there at Colorado?

Yes. Chris and I were office mates at graduate school. We started at the same time and they put all the entering students in one office. He also had some friends in his social group that came to Colorado at the same time, Penny Boston and Steve Welch. And with some other students, we started our own self-organized independent study class. That was the year the Viking mission landed on Mars. Viking was the first and still the only mission to search for life on Mars. We took all the reports from Viking and read them cover to cover and we decided we were going to figure out how to settle Mars. We became kind of a Human Exploration of Mars Club within our graduate student office. And that was probably the most formative thing that happened in graduate school in terms of career direction. That club was the seed of the Mars Underground and grew to be a widespread movement.

Had I been better informed, I would’ve tried to work on the Viking mission as a graduate student. I might have even come here because Ames had instruments on Viking. But I didn’t know that and, in fact, I was advised in the different places where I did my search that it was too late to get involved with the Viking mission. But Colorado researchers had instruments on the upcoming Voyager mission. This was a mission to fly by Jupiter and Saturn then Uranus and Neptune, but the next target was Jupiter. Because I had all this background in atmospheric science from having worked on the GATE field experiment and had taken undergraduate meteorology classes, I did my thesis work on the atmosphere of Jupiter. But my real love was always Mars so when I finally came to Ames as a post-doc, I just started working on Mars related things.

Was it your contact with Chris and others that got you to come to Ames?

Chris came to Ames initially as a summer intern before he graduated. As a result of that, he established relationships with the Ames community and when he graduated he immediately took a post-doctoral position at Ames. When I graduated I took a postdoctoral position at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder Colorado, where I already lived. There I worked with Steve Schneider, a famous climate scientist. But I was not fulfilled there because I really wanted to work in planetary science. One day at NCAR I met a visiting scientist who was from Ames and he encouraged me to apply for a postdoctoral position there. And, of course, I knew Chris was already here, so I jumped at the chance and came out for a visit, then put in an application and got the position. Also, I was very lucky because I got a permanent position within one year.

Terrific! That’s a wonderful path that you’ve taken and it’s probably even more direct than many of them that we have heard about. So you’re here and now tell us about some of the kinds of things that you’ve done, maybe some of the findings that have happened in your career, it’s now been over 30 years, and especially how you might justify it to the taxpayers as being something of value that they should support.

So, kind of a proof of concept then?

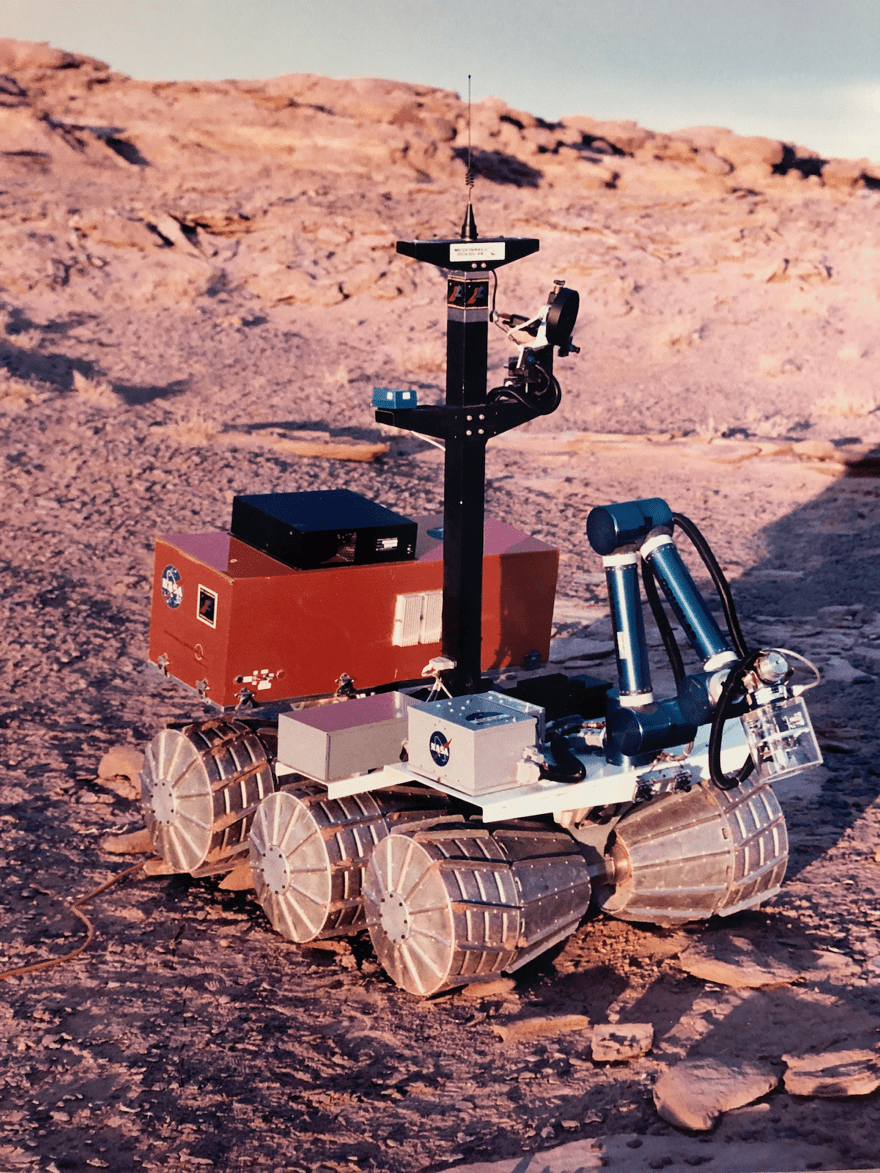

I think that my early work played a major role in what ultimately became NASA’s use of robotic rovers to explore planetary surfaces. First, it started with the question: what do you need to operate a rover and make the data understandable? Does it help to have an immersive experience? My first venture in this telepresence area occurred in the late 1980s before we had any access to surface rovers. I worked with a team of roboticists and we got an opportunity to do a field experiment in Antarctica in ice covered underwater environments. We did robotic exploration with underwater vehicles. We purchased a small tethered robotic underwater vehicle and we outfitted it with stereo cameras mounted on a pan and tilt platform and a communication system that would allow the operator on the surface to wear sensors on their head and move the stereo cameras on the rover underwater with their head. The operator wore goggles that put the camera display directly in front of their eyes. This way the operator was telepresent. For the vision system, we took apart Hi8 video camera viewfinders to build the display because there wasn’t anything that you could buy on the commercial market for less than a million dollars in the way of a head mounted display. There were virtual reality headsets in those days for very high-end military, pilot training kinds of things, but they were super expensive. And we, of course, couldn’t afford that kind of stuff, so we built our own equipment. The first Antarctic expedition focused on exploring microbial mats in an ice covered dry valley lake. In the second year, we performed surveys of marine organisms that live under the sea ice off shore from McMurdo, the main US base. We set up a satellite communication network that allowed us to send our data back to NASA Ames and the vehicle could be driven telerobotically from here. We even demonstrated the construction of a virtual world with the data during real time operations. After finishing that experiment I was next able to get access to a prototype planetary surface rover that was built in Russia. This is the Marsokhod rover. At that time there was nothing that NASA had built in the way of surface rovers, and no companies were building rover vehicles. The Russian group had built the Lunakhod rover that was sent to the moon in the Apollo era, and Marsokhod was a prototype of a Mars rover. Once we got access to Marsokhod, we started doing field missions with it with science instruments mounted on it and we built a robotic arm that deployed instruments and could acquire samples. We put the rover in the field in desert sites in Hawaii and California. I organized groups of scientists who directed the rover and looked at the data from a remote location. Rover data was used to build a virtual reality world and we displayed data that way to the science teams. We did several of these field experiments involving many of the people who ultimately went on to be the science team for the first rovers on Mars. I think I helped train the geology community in rover operations before there were such missions.

That’s exciting! What does a typical day look like for you and what do you like best and least about your job?

Well, a typical day usually involves several different tasks. It may involve working with an engineer who is designing some hardware, participating in a project meeting, working on writing some results from an experiment, that sort of thing. The part I like best is still doing the fieldwork. Fundamentally I’m a pretty active person and I really like being outdoors. I have spent a lot of time doing the field experiments and most recently that’s been in the Atacama Desert of Chile, on a project called ARADS, which is led by Brian Glass, one of the Code T roboticists that I’ve collaborated with for many years.

And what do you like least about your job?

Well, let’s see. I’d say it’s the endless online forms that we have to fill out. And wading through a lot of emails. Doesn’t everyone say that? (laughs)

Yes indeed, you are not the first!

Have you ever thought that if you weren’t doing this as your career what a dream job for you might be? Although I guess this is actually your dream job because you dreamed it!

Well, actually in my dreams I was actually on Mars, not just dreaming about working on it.

What did Mars actually look like in your dream?

Well, I don’t remember a lot, but it was red, and I do remember being on this grassy plain where the grass was red, and it was blowing in the breeze. It was a dream Mars after all.

You kind of came into this obsession, if I can call it that, or preoccupation, or this interest in Mars, about the time the first lander was there and they actually had some pictures of what it was like, there’s one in the conference room, that shows it’s just rocks and there are no trees, but it was red.

The Viking lander got the first pictures of Mars from the ground. When I was growing up there was no data to form an idea of what the surface of Mars looked like. The space artist Chesley Bonestell collaborated with Walt Disney and Werner Von Braun to make some television shows about how Mars might look but I doubt that I ever saw them.

Not even color TV! Did your family encourage your interest?

I wasn’t discouraged but it wasn’t like “there’s our genius daughter, we’re going to make sure she gets all the best of everything”. It was more like in Utah girls largely got married right out of high school and had babies right away. Seriously, that’s what most of my high school friends ended up doing. College was kind of a rare thing but I was sure that I would go to college from my early years. Mine was the first generation in my family to go to University.

So, when you’re not working what do you do for fun?

Well, mostly it’s outdoor sports.

Like which ones?

I typically spend weekends bike riding or hiking or skiing. Since growing up in Utah and graduate school in Colorado, skiing has always been a part of my life. I have a seasons pass at Tahoe which includes some days in other resorts like Colorado and Utah. I really like to go skiing in Italy for both the skiing and the other cultural things to do. The Dolomites and the Italian Alps are awesome. I have done a lot of river trips. I first started rafting in Utah in college and I have done a lot of white-water rafting and kayaking like multi-week white water trips down the Grand Canyon, and sea kayak trips in Alaska and Australia.

How about hobbies, interests, talents, music, anything like that? Or what kind of music you like to listen to?

I learned to play piano in childhood and later taught myself to play guitar, but I don’t play very much anymore. I listen to bluegrass and folk music a lot, strangely. I listen to KPIG radio, a really good Santa Cruz radio station that plays that kind of thing. I also like world music and of course good old rock and roll.

There’s nothing strange about that! That’s good music.

I think my major hobby if you can call it that, is travel. I have traveled extensively throughout the world both for work and for fun. I think that is why I enjoy fieldwork so much.

What about home life, pets, things like that? Do you like to read?

I don’t do much reading for fun these days unless I am on vacation, mainly because I spend so much time reading for work and I rarely have much free time. Most of the non-work reading that I do now is on my phone or tablet. I don’t have pets because I travel too much to take care of them.

Pets are fun to have. We used to have a cat, a couple of cats, but then you always have to make arrangements for them when you travel.

Right! I live in the Santa Cruz mountains and it’s a beautiful place to live, but it is kind of wild where I live. We had a mountain lion walking through our yard every night for two months, and it ate all the neighborhood cats. We and other neighbors who installed motion-activated cameras caught it on video almost every night for two months. Not a good environment for cats unless you keep them indoors.

Wow! You have to be careful with pets if you have that going on.

What advice would you give to a young aspiring student who would like to have the kind of career that you are having here at NASA? Besides, take math earlier than you did (laughs).

I think you have to understand that being a scientist is something that has to be the dominant thing in your life.

It sounds like from your point of view, it has to be something that you really feel.

You have to just feel compelled that you have to do it, you know. If you have other choices and interests, you probably should take the other choice because it’s not an easy career to have. It’s become extremely competitive. I had it pretty easy compared to what people face now. But it can be just very rewarding. If you feel that you have to be a scientist, then be a scientist and make it happen. You have to start early, you have to work very hard, you have to be extremely dedicated. Just don’t give up and don’t let anybody tell you “you can’t do it”. I think it was Thomas Edison who said that “genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration”. And I think that’s really true.

That’s a good quote because one of the things that we ask is if you have a favorite quote.

Well I saw that you asked about a favorite quote and one of mine is posted on the wall of my office: “Failure is not an option!”. That is from Gene Krantz, the flight controller during Apollo 13.

That’s a great one for NASA! And we also ask about favorite pictures that kind of motivate you or that you like, that might have to do with your career or perhaps not. Do you have a favorite picture of Mars for example? Or maybe a place where you went in the field? And you can think about that question and get back to us with any pictures that kind of paint your profile a little more broadly than what your coworkers would know about you if they only knew about you from your work here at NASA. And we also ask who or what inspires you? Or you can give that some thought and get back to us later because it’ll take us a little time to transcribe this interview. It sounds from talking to you like Carl Sagan may have been someone like that in your life. Did you ever get to meet him by the way?

Actually, I wrote my first paper with Carl Sagan!

OK, there’s a little bit of trivia. That’s terrific!

Carl was very inspirational, actually, I think he inspired a lot of people. Because he was the face of science during his era.

His name has come up in a number of these interviews, yes.

Carl Sagan and colleagues were doing research on the origin of life and producing compounds in the laboratory they called Tholins. These compounds are produced in the reducing atmospheres of the outer planets and moons like Titan. Penny Boston and I were graduate students and wanted to see if these compounds could support bacteria as their sole source of food. So we approached Carl Sagan to see if we could get some Tholin from him. And he agreed to send us some and participated in the research and writing the paper. He was a great guy and very supportive. We collected samples from a variety of environments and incubated the samples with Tholins to get cultures. We proved that a wide variety of microbes could grow on Tholins, so they could be the main food source at the start of life on other planets or even on Earth.

That’s interesting. Can we go back, and have you talk about modern life on Mars?

My main career focus for many years has been the search for life on Mars, and by life I really mean modern life, rather than fossil evidence of ancient life. One key reason for that focus is that my work with field robotics convinces me that robotic missions will not be successful at finding convincing evidence of ancient life. However, I think that relatively simple robotic missions can find conclusive evidence of modern life and provide definitive answers. To me, the most compelling target for the search is widespread ground ice in the high northern latitudes. I was part of the Phoenix mission to Mars that went to a site at 68 degrees North latitude into a region where there was near surface ground ice. On that mission, I was the lead for the science working group that assessed the mission results in terms of whether the environment could be habitable for life either at present or in the recent past. We found that the site has all the necessary ingredients for life in terms of nutrients and energy, but because the current summer climate in the martian arctic is very cold, it is too cold for earth like bacteria to be metabolically active. But the climate in that area changes rapidly and dramatically, and this happens on short timescales. The reason for this is that the tilt of Mars axis changes over time. So as recently as half a million years ago, conditions at the surface were warm enough to allow liquid water to form from the melting of the near surface ice. And 5-10 million years ago there were periods when the ground ice should have melted down to 1 meter deep. This is an area where life could persist, growing when conditions are warm enough and remaining frozen, but not dead, at the present time. Organic compounds produced when the biology is active should build up in the ice that can be detected with instruments that are well developed or even flight ready now. Ames has been working since Phoenix on a mission concept to test for life in this area. And I have been on several field experiments to test technology for drilling into the subsurface to get samples to search for life and analyzing those samples for biosignatures. That most recent set of experiments have used a rover carrying a drill and the set of instruments that we would like to fly to Mars deployed to the Atacama desert in Chile. The Atacama is the driest place on Earth and is a good Mars analog for that reason. Our drilling experiments have shown that we can detect signatures of biology that are remnant from a wet period at least a million years ago and were drilled from a meter below the surface.

So that’s a perfect segue because I have to ask you this question: if they offered you a one-way trip to Mars would you go?

That is an interesting question. When I was young and we had just landed on the moon, I expected to go to Mars in my lifetime, for sure. Right after Apollo, NASA presented to the president a plan to land humans on Mars by 1984. And I have no doubt that could have been accomplished if the pace of Apollo had been sustained. But the program was cut after Apollo and the most important element, the big rocket, the Saturn V was stopped in favor of the Space Shuttle. It is actually much easier to get to Mars than to get back so one way trips have been proposed. But at the start, before there is much infrastructure and few people, I think it would be pretty lonely. But if you are part of a small tight-knit crew that could be a great way to spend your life.

Who inspires you now?

The person that inspires me the most right now is Elon Musk. He is a rare combination of inventor, engineer, and industrialist the likes of which the world has maybe never seen before. A cross between Werner Von Braun , Henry Ford, and with a bit of Thomas Edison thrown in possibly. He is creating the positive future of science fiction with his own companies, and he seems to be having fun doing it. He’s changing the game in lots of different ways, not just in Space. Tesla has been a game changer in the transportation field. He has changed the possibility of humans going to Mars, and human exploration has motivated me from the very beginning. And humans to Mars has been a NASA goal really since Apollo but we never seem to make much progress. In fact we’ve gone backwards since the Apollo program which is 50 years ago now. Elon is really changing that by his own work and his own company and his own money and he’s just making it happen. And that is just so inspirational to me.

Plus, he put a car in space, so how can you top that? Carol thank you for spending some time with us and sitting for this interview.

You bet!