This article is from the 2020 NESC Technical Update.

NASA is planning missions that will operate high-performance optical payloads with highly vibration-sensitive scientific instruments for science observations. Stringent pointing stability requirements to mitigate jitter and microvibration are key for such large space telescope missions of the future. Managing jitter is essential to obtain distortion-free images of planetary bodies on exo-planet coronagraph missions. Traditionally these space observatories have relied upon reaction wheels to provide the attitude-control torques needed for stabilization and pointing. For example, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) uses four reaction wheels as part of its pointing control system. However, the reaction wheels themselves are typically the largest pointing disturbance source on the spacecraft, primarily due to static and dynamic mass imbalances in the flywheel as well as wheel-bearing mechanical noise. Therefore satisfying stringent jitter requirements for missions, in this class requires methods to limit or isolate vibrations generated by the wheels. On most high-performance observatory missions GNC engineers typically invest significant time and resources to conduct special reaction wheel disturbance characterization tests, exquisite wheel balancing, and the design and development of wheel-disturbance mechanical isolation devices.

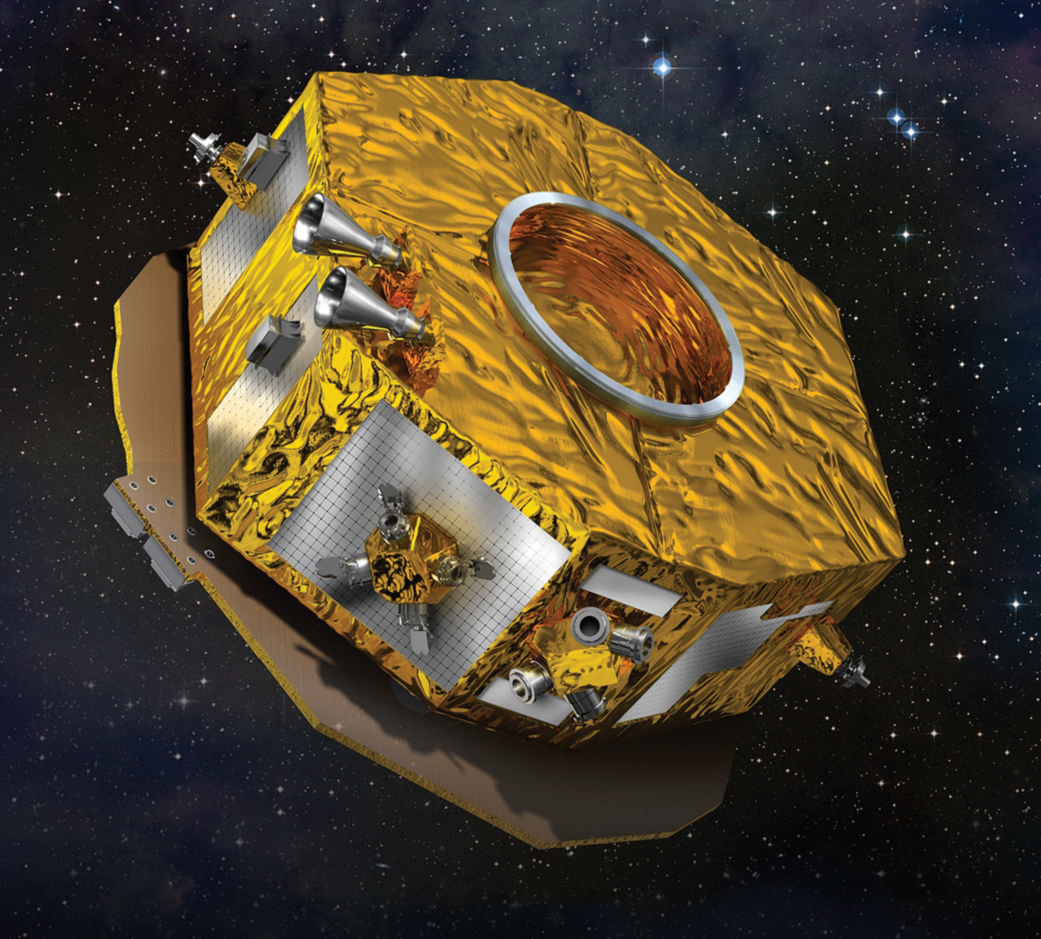

A recent NESC assessment investigated the feasibility of using microthrusters as an alternative or supplement to reaction wheels for providing attitude control during periods of scientific data collection requiring precision pointing. Microthrusters, or micronewton thrusters, are thrusters capable of producing forces in the micronewton range. Microthrusters have been developed by NASA as part of a drag-free control system for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) mission. Microthrusters come in different forms, using different types of propellant. The NESC assessment focused on cold-gas microthrusters that use gaseous nitrogen and on colloidal microthrusters, a type of electrospray thruster that applies a high electric potential difference to charged liquid at the end of a hollow needle in such a way that a stream of tiny, charged droplets is emitted generating thrust. Both cold-gas and colloidal microthrusters were flown on the NASA ST7/ESA LISA Pathfinder technology demonstration mission.

The assessment team recognized that the need for the observatory to perform large angle slew maneuvers would exceed the control authority of microthrusters, necessitating the use of either wheels or traditional reaction control system (RCS) thrusters (using hydrazine or bipropellants) for large slews. The need for different control actuators for large slews and fine-pointing leads to different mission operational scenarios studied by the team. One scenario used reaction wheels for performing large slews, which are then spun down to zero speed during science observations, with microthrusters used as the sole actuator for fine pointing. In this scenario, any need to mechanically isolate the reaction wheels is eliminated because the wheels are shut down during fine pointing. A second scenario employed RCS thrusters for large slews, with microthrusters used as the sole actuator for fine pointing. Both the cold gas and colloid microthrusters with their nanonewton resolution provide an appropriate level of attitude control torque to maintain the observatory’s fine pointing without introducing undesirable jitter. The assessment results indicated the microthrusters could provide an order of magnitude performance improvement relative to HST. The general conclusion is that microthrusters have potential for reducing the cost and technical risks of achieving demanding pointing stability performance on observatory-class missions.

For more information, contact Cornelius J. Dennehy, cornelius.j.dennehy@nasa.gov or Aron Wolf, aron.a.wolf@jpl.nasa.gov.