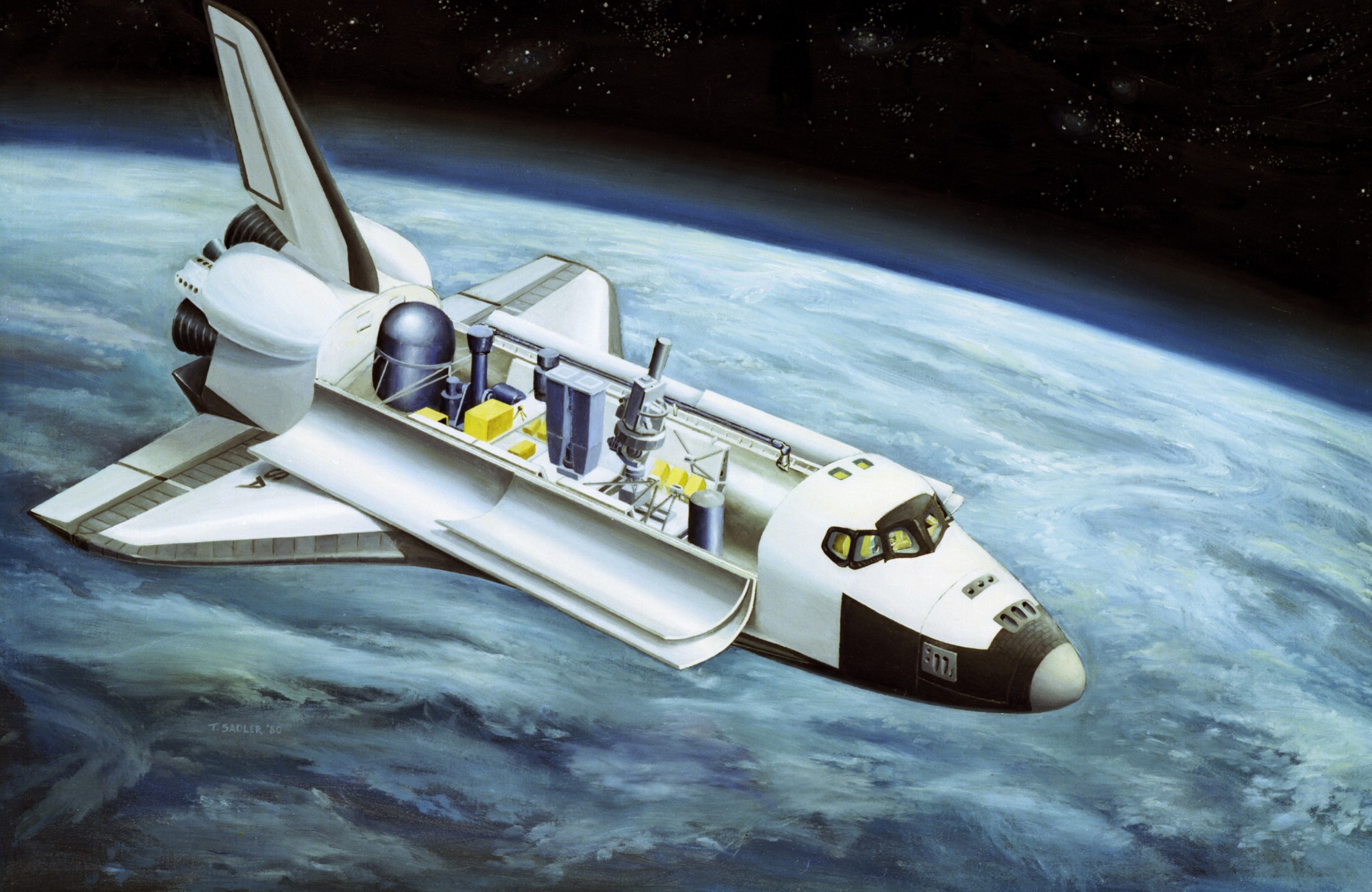

Long before Teresa Vanhooser became Marshall Space Flight Center’s deputy director, she — like many others here at the center — was heavily involved with Spacelab, which first launched 30 years ago on Nov. 28. It was a lab that paved the way for the International Space Station and taught us how to do science experiments in orbit. Below, Vanhooser shares about her experience as a manager during the days she describes as “an awesome time in NASA’s life.”

Please talk about the progression from Spacelab to ISS you’ve witnessed. What stands out to you? Any challenges?

For Marshall Space Flight Center, Spacelab helped gain skills needed to work on the International Space Station. We learned about payload integration as well as building and managing complex hardware like Spacelab modules and pallets. We proved we had the skillset to support critical roles on the space station. I think it was really just a tie from Skylab to Spacelab then on to the station. It was that continued effort down what I call our “swim lane.”

Our Spacelab operations experience helped Marshall add value to the space station program and communicate the rationale for the Marshall Payload Operations Integration Center. As station got underway, we had to figure out how our control center would work with the Mission Control Center in Houston and with all the other control centers around the world. There were bumps early on, but once we all settled in, it became very smooth and that still continues today.

What are your personal highlights from Spacelab?

To me, the best thing about Spacelab was being able to see something from start to finish in a short period of your career. Within four to five years, we went from the mission inception to flight. We got to see all aspects of that. All the way from trying to figure out what the configuration looks like through the analytical integration, physical integration and then the flight operations. And you can do that in a very short amount of time. The satisfaction of seeing what you started working on all the way through the success of it was a very unique part of what Spacelab was all about. For me, the ones that I was heavily involved in — the Atlas-1 and -2 missions, and the Microgravity Science Laboratory-1 — were my highlights just because I was more involved from the early stages. The delight of seeing scientists so excited about getting their data from their instruments at the close of the mission was probably the best reward that I could have gotten because that was worth all the hours that we spent.

How did payload operations change from Spacelab to space station?

On Spacelab, it was how much can we cram into 10 to 16 days. Every minute was planned and every minute, we tried to get as much science as possible. It was always at a fast pace and with a lot of urgency. Whereas on space station, we tried to get to the point where it was “OK, we have time.” There’s not that same level of urgency. Although you want to use the time you have, it’s not like it has to be tomorrow or you’ve missed it. It’s a little more of a relaxed environment particularly with the payload side. The payloads are up there for an extended amount of time. If something doesn’t work the first time, you can make modifications and run it again. On Spacelab, in some cases, if you missed your opportunity, everything else was so planned, you never got a second chance.

In your opinion, how did Spacelab advance us to the International Space Station?

Spacelab taught us a lot about how to operate in the space environment. You only had the two weeks and if something went wrong with the hardware, it would come back on the shuttle, so you could figure it out and potentially re-fly it on another mission. Even the hardware and experiments that didn’t work as well as planned provided a learning experience. Once you fly something to station, it’s normally up there for six months or longer. Spacelab really taught us what to expect with regards to space environments. We could implement that when we were doing our designs for the station because we had all that data in hand. This helped us create better designs and anticipate what issues we might have. Plus, we were able to take existing payloads, and make modifications to them for ISS.

What did we learn about payload operations during Spacelab that helped us prepare for 24/7 operations on the space station?

We learned about shift work and what we can expect from our folks relative to that. The Spacelab time showed us how to manage people and lead teams. And how to manage the shifts and produce products we needed to be able to successfully plan and implement a mission. That was the first step. We could do it for a short, two-week mission. Now how do we apply that forever? A lot of people had a concern whether we could support 24/7 operations continuously because we were used to the short duration. We learned what we should and shouldn’t do when we actually got to continuous ops. We learned how to pace ourselves and how we should set the right expectations. What do we need to do to train the crew for science operations? How much data can they absorb? How detailed do the procedures need to be? How long does it really take to conduct an experiment? All those aspects really factored in to our planning. By learning about them on Spacelab, we were able to take those to the next level for space station.

What did we learn about helping payload developers prepare investigations for flights in an orbital laboratory? How is this different for space station?

I don’t think it’s much different for space station except they have to think about longer duration. But as far as us helping them, they don’t always think about how much more difficult it is to operate in microgravity. The advantage that we bring to the table is because we have worked with Spacelab payloads, we can help them with their design and tell them whether it will work or provide detailed help like telling them they need to change these fasteners. Or it’s not good that the crew has to take that many things apart to fix something. What we learned on Spacelab is how to make the design more crew-friendly, both from an operational standpoint but also from being able to fix it. If there are easy changeouts, they can do the repairs on orbit. That’s what is beneficial, because it’s up there long term. You can’t just bring it back whenever you want to, repair it and send it back up there because of launch costs and available up-mass. This is all good practice for exploration missions even further away from home with the Space Launch System.

What did we learn about working with Mission Control at JSC?

We learned the functions are completely different. They were really focused on making sure the vehicle was working. Their focus wasn’t necessarily on the science. At MCC it was about the crew, and the health of the crew and the vehicle. Not that we didn’t care about that. That just wasn’t our role. We were completely focused on what science can we do. How can we get some time in with the crew for experiments? We developed a mutual respect for what the other brings. The longer we worked together, the better it got. They respected that our role was to get as much science as we could get. We respected the fact that they need to make sure things are in working order. So what has to be done on space station now is a balance. You can literally spend all of your time doing one or the other. But what is the right balance? It is an orbital science lab. We didn’t put it up there just to maintain. We put it up there to do science.

Since we finished assembly of the station, there has been a big turn toward the science, which is great to see. We’re in the spotlight now. Mike Suffredini [manager of the International Space Station Program] said that himself. They [MCC] have a breadth of experience in the real-time operations, we learned a lot from their experience level but we also learned to respect each other for what we all bring to the table. Our relationship with them now is better than I’ve ever seen and that’s because of people working together for a common good.

In my personal opinion, Spacelab was just an awesome time in NASA’s life because of what were able to accomplish and, from the science side, being able to do it in such a short timeframe. When things are smaller, you have a lot more control than when something is as huge as a space station, so Spacelab was a good stepping-stone. Without Spacelab, I think we would have had more bumps and more of a learning curve on station.