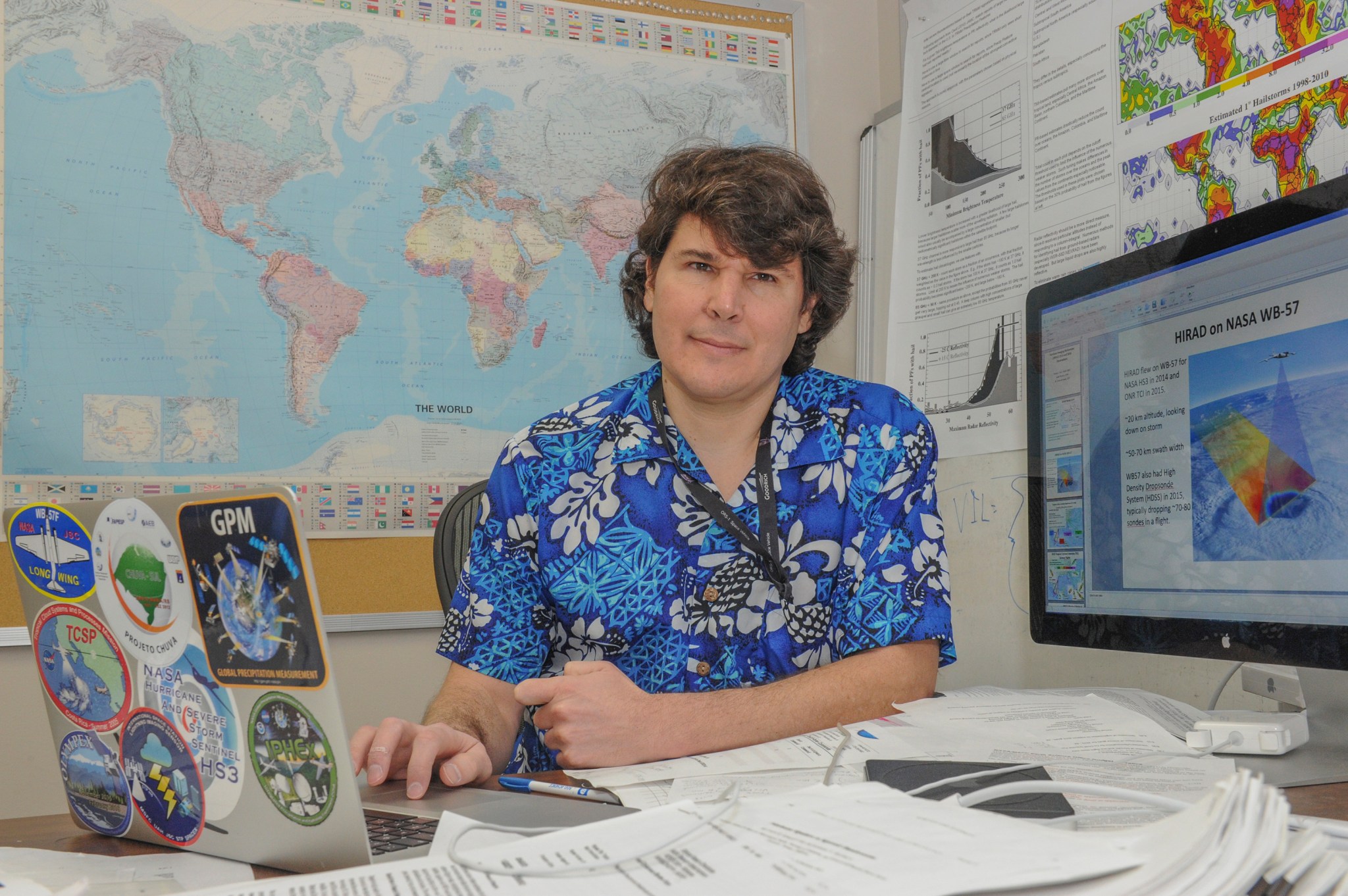

Despite what Earth science researchers know about hurricanes, NASA’s Dan Cecil understands that there are always more questions than answers. That’s what makes the job so interesting. Cecil, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, studies the internal dynamics of hurricanes to unpack some of those questions and help coastal emergency managers better prepare for storms to come.

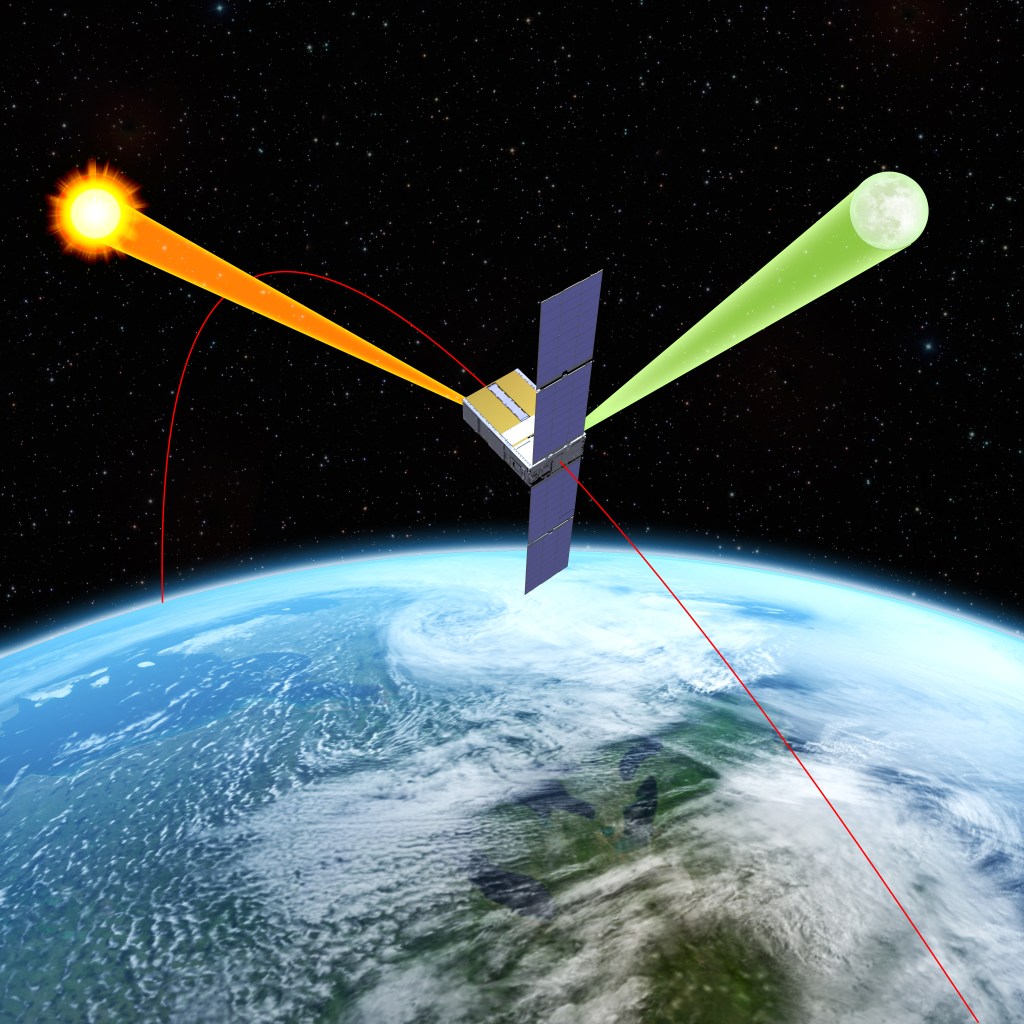

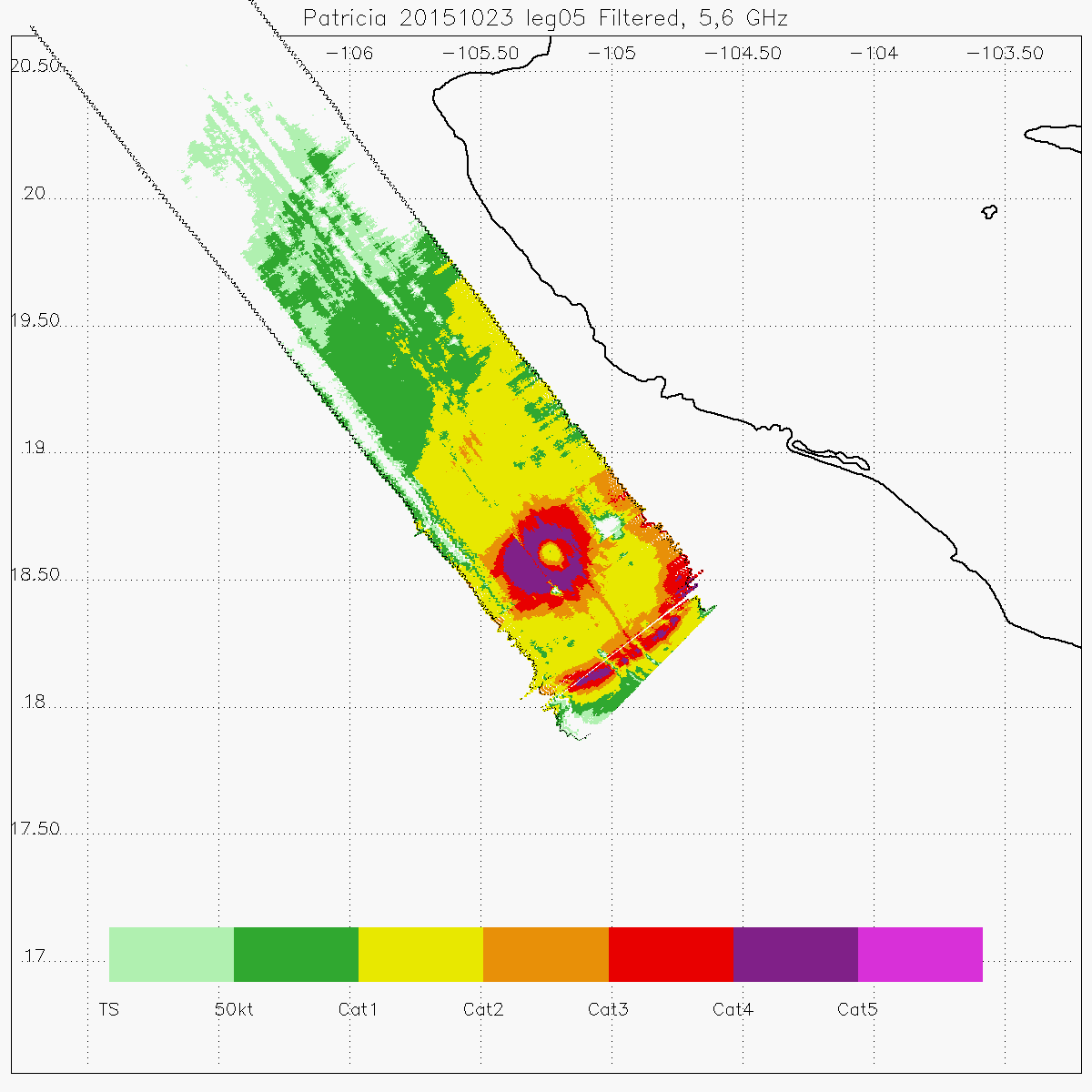

Cecil uses an experimental instrument called the Hurricane Imaging Radiometer, HIRAD for short, to gather detailed information about wind speeds and rain intensity inside hurricanes. HIRAD peers through a storm’s heaviest rains and thickest clouds to measure strong winds at the ocean surface. These measurements help glean important information about why hurricanes behave the way they do – information that improves forecast models.

With HIRAD mounted in the underbelly of NASA’s high-flying WB-57 aircraft based out of NASA’s Johnson Space Center, NASA pilots flew ten manned flights over four named storms – Erika, Marty, Joaquin and Patricia – during a record-breaking 2015 hurricane season. The WB-57 reaches altitudes high enough to fly over the storms – above 60,000 feet – and provides data that is in some cases more detailed than what satellites provide.

The investigations were part of the Office of Naval Research’s Tropical Cyclone Intensity experiment, or TCI 2015. TCI is an Office of Naval Research Direct Research Initiative collaborative experiment with the Naval Research Laboratory, industry, and universities. A key focus of the research is to study how hurricanes change and intensify.

Cecil will discuss findings from 2014-2015 hurricanes at the American Meteorological Society Annual Meeting Jan. 11 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Ahead of the meeting, he took some time to sit down and talk about his work.

Why is it important to study hurricanes?

Hurricane Katrina caused upwards of 2000 deaths and $100 billion damage in 2005. It could have easily been much worse, if not for weakening just before landfall and tracking a little east of what would have been a “worst case scenario” for New Orleans. A few historical hurricanes hitting India and Bangladesh, called “cyclones” in that part of the world, have caused over 100,000 deaths each. We will never eliminate all the deaths and damage from hurricanes. But the more we know about their structure, and the better we can forecast them, the more we can limit those impacts.

What has working with HIRAD taught you about hurricanes in general?

Working with HIRAD reinforces for me how hard it is to really determine the strongest surface winds in a hurricane. HIRAD measures energy that is related to the amount of foam on the ocean surface, and that foam coverage is related to the wind speed. It maps this out over a larger area than similar instruments, so it has a better chance of “finding” the location with the strongest wind. Directly measuring the strongest wind (with an anemometer, or similar) is almost impossible, because the odds are your instrument will not get to quite the “right” location for the strongest wind. Even if you get your instrument to the right location and it returns data, interpreting the measurement is difficult. Did you measure a gust or a sustained wind? How do you define the “surface” wind, when the surface is a violently churning mixture of sea spray, air, and breaking waves, and those waves are bouncing the surface up and down by 30 feet or more?

How did you become interested in Earth science?

From the time I was a small child, I was fascinated by clouds, weather maps, radar pictures on TV, watching the rain or snow fall. When I found that my first college classes were not as interesting as I expected, I thought about changing majors. Then I caught myself spending about 20 minutes just staring at clouds, watching them grow, fascinated, and realized I would regret switching to anything else.

What makes a good scientist?

Words like “skeptic” have gotten a negative connotation lately, but a scientist is supposed to be skeptical. Question your models and your pre-conceived notions. Question your data. A good scientist has to be able (and willing!) to observe what is really happening, and figure out how to either reconcile that with a conceptual model or create a new conceptual model. If your observations do not fit your model, maybe your data is bad, maybe your model is bad, or maybe both are bad. When observations and models do not match, that is usually when we start to learn something interesting.

Do you have a story or work experience that sticks in your mind and speaks to the impact of what you do?

It wasn’t really a work experience, but the April 27, 2011 tornadoes here in Alabama stand out. I was lucky in that I only lost some shingles in those storms, but I couldn’t get to my house until around midnight and had to drive around debris to get there, not knowing what I would find in the darkness. The next morning I walked to what used to be a neighbor’s house, and helped pick up the unrecognizable pieces. When the girl who lived there spotted keepsakes from her bedroom in the rubble across the road, digging them out became a priority.

I was scheduled to go to Oklahoma a few days later for a project taking measurements of thunderstorms. I told my colleagues there I was never so glad to be in Oklahoma, safely away from our tornado alley!

For more information about HIRAD, visit:

For more information about TCI, visit: