Detailed findings about the size, power and impact of the Chelyabinsk meteor, which streaked across Russian skies on the morning of Feb. 15, 2013, were published Nov. 6 in a pair of acclaimed science journals by an international coalition of space scientists — including astronomer Bill Cooke of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., and several other NASA researchers.

The teams of astronomers, “cosmochemists,” “meteoriticists” and other space-science specialists, having painstakingly gathered and analyzed a wealth of data about the event from civilian observers and amateur videographers, authored three papers — two in the latest issue of Nature and another in the newest edition of Science.

The atmospheric entry and airburst of the meteoroid over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk injured approximately 1,600 people on the ground. Shattered windows or structural damage were documented in more than 7,200 buildings, according to officials in that city.

Cooke said the event — unprecedented in modern times — provided a valuable opportunity to study a rare but natural hazard that often preoccupies him as manager of the Meteoroid Environments Office at the Marshall Center and author of NASA’s Watch the Skies blog.

This video shows a brilliant fireball over Lake Ontario in 2009. Fireballs that drop meteorites are rare, such as the case with the Chelyabinsk meteor. (Western’s Southern Ontario Meteor Network)

“These papers represent efforts by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate and Office of Safety & Mission Assurance, along with the agency’s global partners, to develop a complete picture of the Chelyabinsk event — helping us better understand the behavior and effects of both large and small meteoric impactors,” Cooke said.

“That’s invaluable to our study of near-Earth objects and for the development of strategies to protect our planet from stray asteroids and other hazards from space,” he added.

Unexpected Findings

The findings published in Nature, to which Cooke contributed, reconstruct the path of the meteor and the damage caused by the explosion to determine the origin, trajectory and power of the airburst. The Science paper documents the circumstances that resulted in the shockwave, and establishes a benchmark for future asteroid impact modeling; the field studies that led to many of its findings are archived here.

Most startling? The findings suggest previous theories about the frequency of potentially dangerous meteoroid incursions into Earth’s atmosphere may have been short of the mark. The number actually could be “an order of magnitude higher” than predicted in the past, according to a new Science article about the findings in that journal.

But people shouldn’t worry unnecessarily, Cooke added. “Chelyabinsk-type events are still very, very rare,” he said.

Possible Origin

Also of keen interest to researchers, Cooke noted, was a possible link between the Chelyabinsk fireball and near-Earth asteroid 86039, also known as 1999 NC43. Its orbit brings it past Earth every seven years. (And it’s not to be confused with 2012 DA14, the completely unrelated asteroid that came within a history-making 17,200 miles of Earth just hours after the Chelyabinsk event.)

Of asteroid 86039, Cooke said, “It appears to have the same composition as the Chelyabinsk meteor, and their orbits are very similar.” And, he suggested, it would take a “kick” of just .7 kilometers — about 765 yards — per second to send a piece of 86039 onto a path intersecting with Earth.

“Is Chelyabinsk a chip off 86039, ejected within the past few thousand years?” he asked. “If so, how did it get separated from its parent? A collision, maybe?”

He smiled. “Always another mystery.”

What’s Ahead for Near-Earth Object Research?

In the wake of the Chelyabinsk event and these new findings, the Meteoroid Environments Office at Marshall, the Near-Earth Objects Program Office at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and other NASA and partner organizations continue to work to develop better ways to detect potentially dangerous near-Earth objects, or NEOs, and to develop strategies for deflecting any found to be on a collision course with Earth.

Cooke and Paul Chodas, a research scientist in the Near-Earth Objects Program Office, took part in a media teleconference Nov. 6 to discuss the Chelyabinsk findings and provide updates concerning NASA activities to search for, detect, characterize and track NEOs. They were joined by Peter Jenniskens, a meteor astronomer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., and co-lead author of the Science journal paper; and by NEO Program Executive Lindley Johnson of NASA Headquarters in Washington. (Audio replays of the telecon are available until Nov. 13, 2013, by calling toll-free at 888-446-2545.)

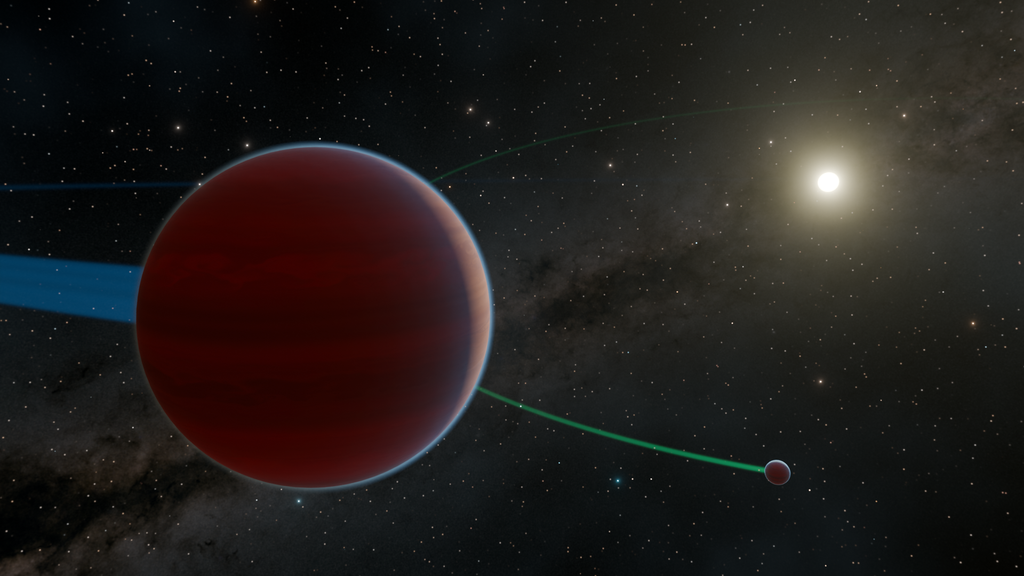

NASA’s recently announced asteroid initiative will be the first mission to identify, capture and relocate an asteroid. It represents an unprecedented technological feat that will lead to new scientific discoveries and technological capabilities that will help protect our home planet.

Aside from representing a potential threat, the study of asteroids and comets represent a valuable opportunity to learn more about the origins of our solar system, the source of water on the Earth, and even the origin of organic molecules that lead to the development of life.

› Read More: A Timeline of Meteoric Descent (pdf)

By Rick Smith

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala.

Media Contact:

Janet Anderson

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala.

256-544-0034

janet.l.anderson@nasa.gov