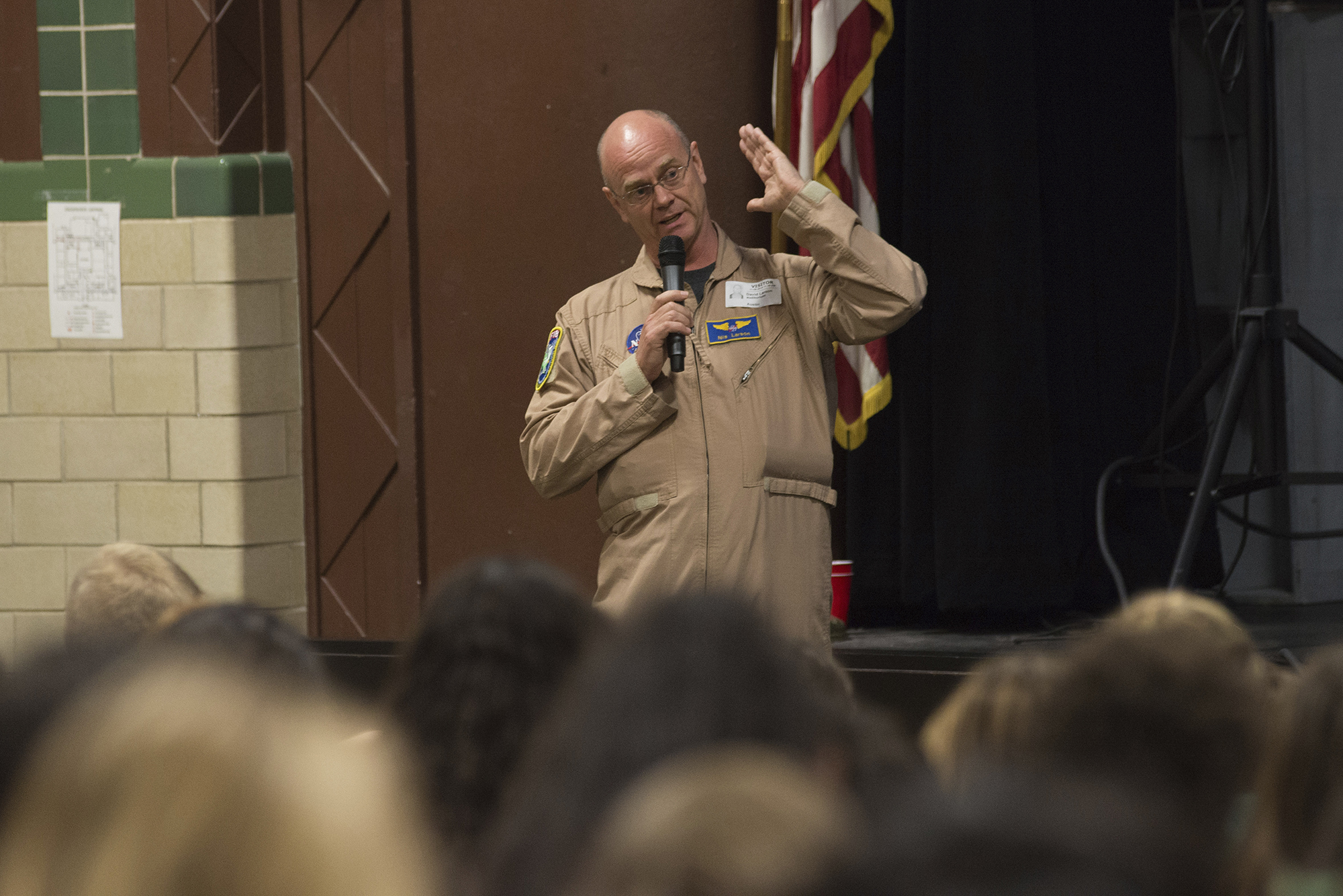

David Nils Larson went to work one morning, attended a few meetings, gathered his life support gear and soon found himself 30,000 feet over the California high desert flying a NASA jet faster than the speed of sound.

At the controls of an F-15 Eagle aircraft, a high performance former military jet NASA uses for research, he climbed and dived. Nils, as he prefers to be called, flew the complex mission as part of ongoing research about what happens to a pilot’s breathing as he or she is flying through maneuvers that produce roller-coaster-like stresses.

The U.S. Air Force and Navy are looking into situations where some pilots are getting sick and for which the causes remain unknown. In March 2017, the NASA Engineering and Safety Center at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia assembled a team to investigate pilot breathing further and Nils was flying one of those missions wearing special gear that recorded his responses.

This is not a routine day, because in the flight research business there are no routine days. For Nils, who is the chief test pilot at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in California, once the mission was complete, he safely landed. Shortly afterward he was completing flight paperwork in the same office once occupied by Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon who worked at the center as a test pilot flying aircraft such as the rocket-powered X-15.

“I met him a few times and it was always such a treat, Nils recalled, “He was such an amazingly nice guy and incredibly thoughtful.”

Meeting Armstrong and sitting in the same office had symmetry for Nils, as it was Armstrong who was one of Nils’ inspirations growing up in Bethany, a small West Virginia town. He recalled always having an interest in space and NASA and using a big log in the backyard as a spaceship to play astronaut.

In addition, Nil’s physical science teacher in high school loaned him a copy of “The Right Stuff,” the Tom Wolfe book about the early days of supersonic flight, rocket planes and astronauts.

It wasn’t long before Nils found himself at the Air Force Academy, where he graduated in 1986 with an astronautical engineering degree. In the Air Force he logged more than 5,500 hours in the air flying more than 75 different type of aircraft – including the U-2 spy plane.

Retiring from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel stationed at Edwards, he didn’t have far to go – just down the taxiway – when he joined NASA in 2007 as a test pilot. Nils continues to fly the most advanced aircraft to conduct experiments and perform research that will help NASA transform aviation for the 21st century.

Most challenging research flights

Research varies from providing air-to-air photographic support of another aircraft flying an experiment to complex tests of new technology through flight that challenge the capabilities of the pilot and the aircraft.

For example, he recalled a particularly difficult set of missions he flew supporting the Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance System, or Auto GCAS. The system was designed to take over for the pilot in situations where human reflexes would be insufficient for avoiding a collision, correct for the dangerous flight condition and return control to the pilot.

“The missions were high-risk flights that were looking at pilot reaction times in avoiding hitting a mountain, so we had to fly near the mountain at high speeds,” he explained. “In other flights, airspeed, altitude and dive angles had to be executed precisely and if the aircraft was too close, or the airspeed was off, the maneuver would get called off.”

Some of the flights produced anxious moments.

“I was going Mach 1.2 straight down from 30,000 feet and activated the system,” Nils said. “In those seconds, it is difficult to imagine how close I was to planet Earth. There was some adrenaline there. Even when I could tell the airplane was not going to hit the ground, I still had the ground rushing toward me and I was experiencing sensory overload. I said to mission control, ‘I hope the data was good because I really don’t want to have to go and do it again.’”

Nils remembers being somber on the day he flew that mission. The area in which he was flying was the same place where a friend, Lockheed Martin pilot David Cooley, perished flying an F-22A in 2009. Nils believes Cooley could have been saved if an Auto GCAS was available then.

The reality of the hazards of flying high-performance jets is not lost on Nils, or his wife Kirsten, who was close with Cooley’s spouse.

Kirsten doesn’t like it when her husband flies dangerous missions, Nils said, and prefers he just not tell her about them. However, years later when the Auto GCAS he helped test led to saving a pilot, it was a moment he was happy to share with his wife.

“When I opened my email and read about the save, I printed it out and handed it to Kirsten,” he said. “She had chills. I told her ‘I know you hated it when I worked on it, but here is a guy coming home to his family now because of that work.’”

A system based on what Nils proved in flight is currently used on a number of military aircraft and is credited with saving eight pilots and seven aircraft since 2014. In fact, Armstrong’s work was included as part of the winning 2018 Collier Trophy submission for F-35 Auto GCAS testing. There also are discussions about incorporating such a system on additional military aircraft, as well as commercial aircraft.

Complex and varied missions

Sometimes Nil’s work includes flying aircraft at different locations to meet research goals.

For example, a recent series of Quiet Supersonic Flights in Galveston, Texas, sought to measure community response to less intense sonic booms, the noise generated by supersonic flight.

The data collection is part of a larger effort involving the X-59 Quiet Supersonic Technology (QueSST) aircraft intended to eventually allow commercial supersonic flight over land – currently prohibited – and greatly reduce coast-to-coast travel times.

To put that in perspective, it takes about 3.5 hours to get to Las Vegas by car from Edwards Air Force Base. For Nils in a high-performance jet, it takes about 25 minutes from takeoff to Las Vegas flying subsonic, but 10 minutes to get back at supersonic speed.

Nils also flies science aircraft like the DC-8 flying laboratory. He flew the first half of the NASA DC-8 26-day mission around the world in April 2018 for the Atmospheric Tomography (ATom) mission. Scientists were studying the atmosphere in the remotest parts of the planet to better understand the processes that determine how greenhouse gases cycle around the world.

Aside from multiple mission locations and time zones, the team had additional challenges. For example, diplomacy and coordination were required with flights over different countries and work days can stretch to 14 hours or more on particularly busy days.

Maintenance challenges with the aircraft also can occur, but Armstrong crews were on location and prepared with key parts and work to avoid trouble and quickly resolve problems when they arise, Nils explained.

The job

Helping to manage all of the logistics required before Nils steps into the cockpit underscores that it isn’t always glamourous being a test pilot. Training, instrument refresher courses, simulations and check rides are part of the work. Another requirement is annual physical examinations until pilots reach the age of 55, after which NASA requires a physical examination every six months. At 54, he will soon need to add that to his to do list.

Also not particularly glamourous, but required to assure mission success before every flight Nils has attended a number of meetings and briefings on the flight, practiced in the simulator if it is a complicated flight, checked the weather, reviewed runway and airspace notices, looked over mission requirements and filed a flight plan.

Flexibility is another key character trait a test pilot must possess. Weather, experiment complications, or technical challenges with the aircraft or the chase plane are just a few of the common impediments that can lead to multiple cancelations or postponements.

“Once you have been involved with flight research long enough, everybody knows when something doesn’t go as planned that it’s the nature of flight test,” Nils said. “When you are researching new things, they don’t always work perfectly. However, we have great teams of engineers and mechanics and if they don’t like it, they won’t let you go.”

One of the perks of being the chief test pilot is the ability to influence the design and operations of a new experimental aircraft. For example, on the X-57 Maxwell distributed electric propulsion aircraft, Nils participated in early concept discussions.

“Being there at the beginning of experimental aircraft study is awesome because test pilots are geeky engineers too,” he said.

However, he also goes to a lot of meetings about developing experimental aircraft that never become actual experimental airplanes, which he refers to as vapor projects.

I’ve got a smile on my face and I’m thinking this is what I always wanted to do and I can’t believe I get to do this.

Nils Larson

NASA Test Pilot

Exhilaration of flight

Before Nils steps into the cockpit, he shakes hands with the crew chief and talks to the crew. After the flight he thanks them for letting him borrow their aircraft, as the crew takes care of the aircraft like it is a family member. He values all of the people who make it possible for him to fly.

But it isn’t until all the checklists are complete and he is waiting to take off that he has time to reflect while looking at the blue sky and wispy clouds above.

“I’ve got a smile on my face and I’m thinking this is what I always wanted to do and I can’t believe I get to do this,” Nils said.

When the wheels come off the runway, “I take a breath and say ‘ahhhhhhhh,’” Nils said. “Everything else, the paperwork, the meetings, the hassles, all fall away and there is just the mission. I come back with a smile on my face.”

Like a true, seasoned pilot, whatever aircraft he is flying is his favorite, but that’s especially true of a high-performance aircraft.

“When I am flying a fighter and light the afterburner that acceleration pushes you back in the seat a bit,” Nils explained. “A full afterburner takeoff in the F-15 Eagle, when I pull back on the stick and I am hauling to 25,000 feet straight up in a few seconds and flip it on its back – it doesn’t get much better than that. That’s just good fun right there.”

When the wheels hit the ground, he’s not disappointed it’s over – he is euphoric and smiling.

“Sometimes when I am walking away from the airplane with my helmet bag, still wearing my gear, I look back at the lakebed and the airplane,” Nils said. “In that moment, it is just as I envisioned when I read the book ‘The Right Stuff’ all those years ago. I think, ‘How cool is this?’ Then I say a little prayer. I look up and say ‘thanks.’”