The Gemini III mission carried two remarkable firsts: an astronaut’s smuggled sandwich and NASA’s first fundamental space biology experiment in orbit.

The Gemini III mission carried two remarkable firsts: an astronaut’s smuggled sandwich and NASA’s first fundamental space biology experiment in orbit.

The first corned beef sandwich to orbit Earth was smuggled aboard Gemini III on March 23, 1965. As contraband unapproved for flight by NASA, pilot John Young had hidden the sandwich in a pocket of his spacesuit shortly before the launch. Around two hours into the almost five-hour long flight, he offered some to the commander of the mission, Gus Grissom, who accepted the rye bread and preserved meat gift. The exchange over the sandwich lasted less than a minute and ended with Grissom putting the unfinished sandwich away in his own spacesuit pocket so the breadcrumbs that were breaking off would be less likely to float behind an instrument panel or into one of the astronaut’s eyes.

The approved food for the flight, meanwhile, was kept in a box next to Grissom. That box contained items like cubed food covered in a layer of gel, preventing the kind of crumb mess that quickly became obvious with the sandwich. Also on the menu for the short flight were more mundane courses like rehydrated applesauce, which the astronauts enjoyed while remarking that there was no pork chop to go with it.

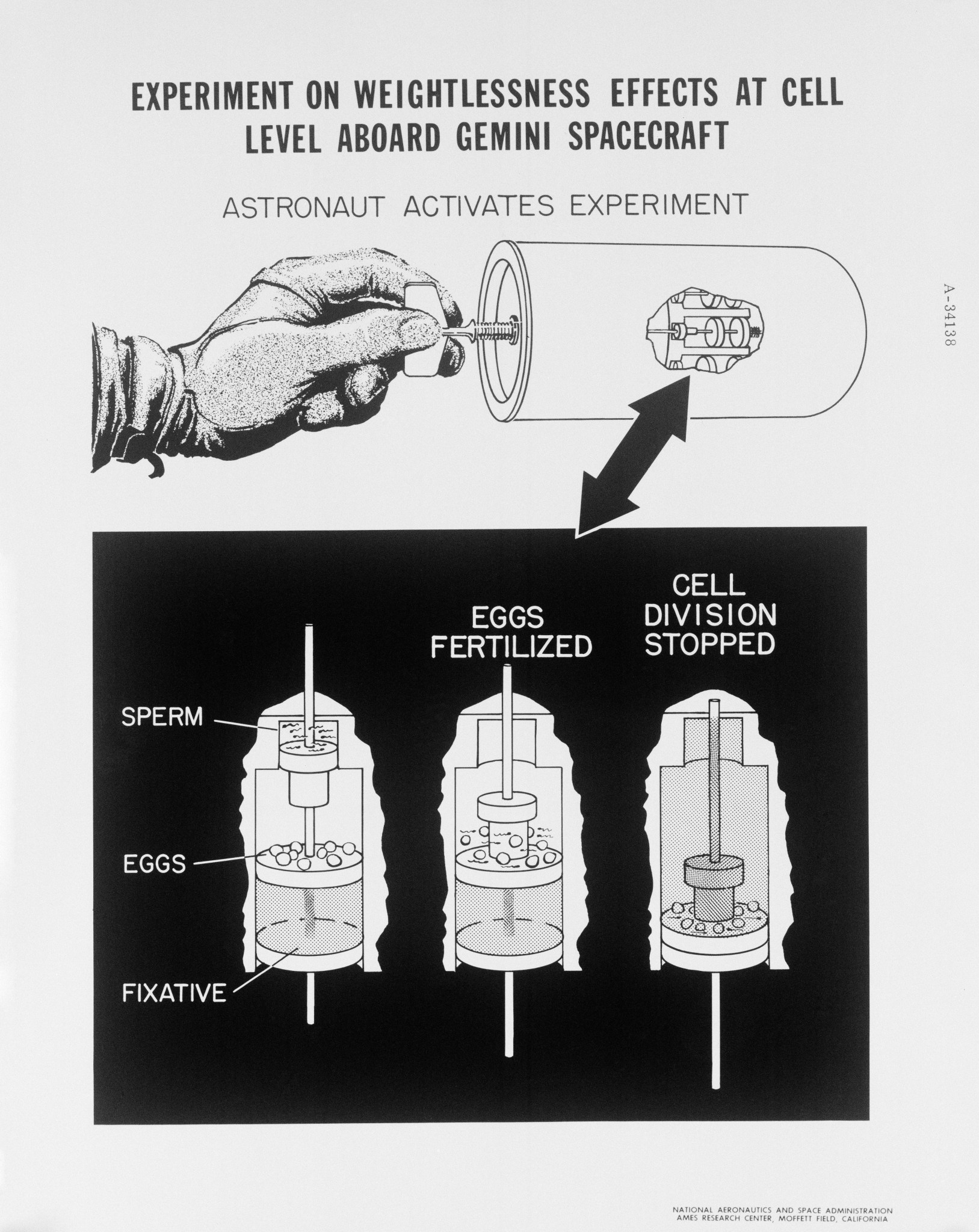

In a separate box near the food was a canister containing sea urchin eggs, Arbacia punctulata. These eggs were not the kind of roe that appears on menus at sushi restaurants and were not intended for consumption. Instead, the canister containing the eggs represented a lesser-known milestone in NASA history: the agency’s first fundamental space biology experiment in orbit.

What we today call space biology — the study of fundamental mechanisms of life, such as metabolism and growth, and how they’re affected by space and spaceflight — traces its NASA roots to the very first years of the agency’s existence. High-altitude balloons and rockets had already carried some species to the edge of space and just beyond, before Project Mercury. Then, the Mercury flights included biomedical investigations into astronaut physiology, while Project Gemini incorporated fundamental biology experiments into the agency’s human spaceflight missions.

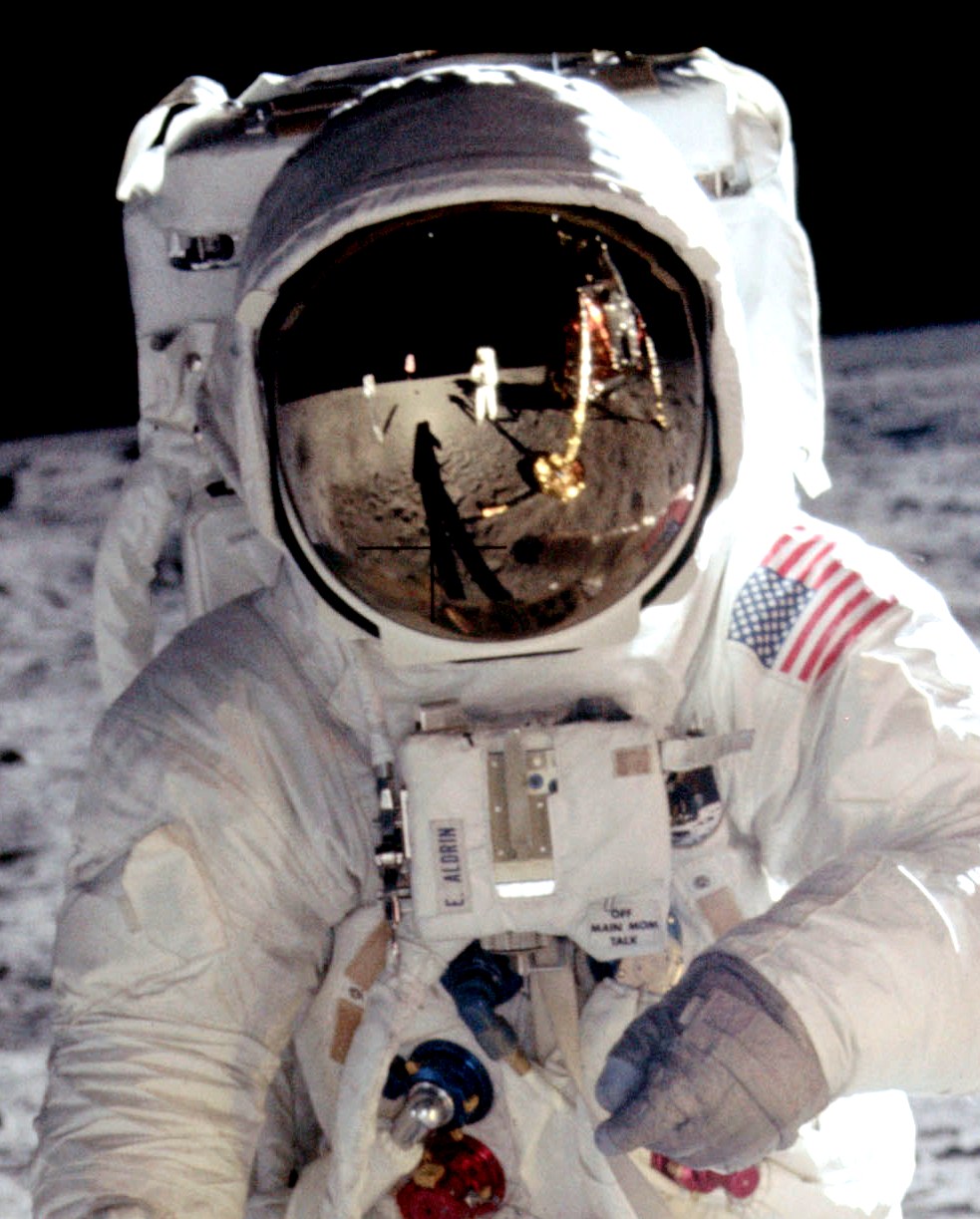

Gemini III was the first crewed mission of the program that tested many new capabilities in space essential for the success of Apollo, such as rendezvous and docking in orbit around Earth, perfecting re-entry and landing methods, and shaping our understanding of the effects of longer duration spaceflight. Over the course of the Gemini missions, astronauts performed 25 biomedical experiments, some of which were modified or repeated up to three times on different flights. Of the 13 unique experiments flown, the astronauts themselves were the test subjects in all but three cases where non-human payloads were used. In addition to the sea urchin eggs, frog eggs and bread mold also were studied. The tests on the astronauts often required a strictly controlled diet before and during the mission to assess how human physiology would respond to spaceflight. Such diet restrictions did not apply to Gemini III, so a few bites of the sandwich would not have disrupted any of the planned experiments.

What did disrupt the sea urchin experiment involved Grissom’s exuberance when turning the handle on the canister to initiate the fertilization followed by a fixative solution at planned intervals during the flight. The handle broke, so the experiment’s objectives were not achieved. The canister was redesigned, frog eggs were substituted, and the new experiment flew on Gemini VIII and then Gemini XII. By the end of the program, it had been demonstrated that cell division could occur in microgravity without detrimental effects attributable to the lower gravity environment.

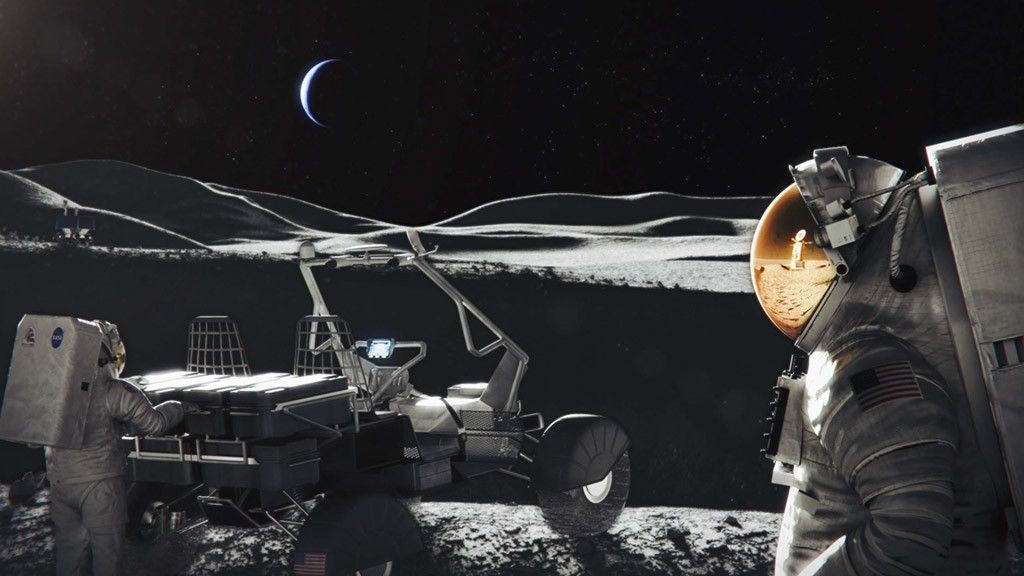

Since the Gemini sea urchin and frog egg experiments, NASA has continued its research in space biology. On the final Apollo mission, mice joined the astronauts to study the effects of deep space radiation. Now, almost 50 years after Apollo 17, the first launch of the Space Launch System rocket for the Artemis I mission will carry among its secondary payloads the BioSentinel mission. The mission builds upon decades of fundamental space biology research aboard the space shuttle, the International Space Station, balloons, and small satellites — all within low-Earth orbit. BioSentinel has developed a biosensor instrument to detect and measure the impact of space radiation on living organisms over long durations — this time, beyond low-Earth orbit in deep space. Rather than sea urchin eggs or frog eggs, the mission will use yeast to address strategic knowledge gaps related to the biological effects of space radiation. And, since the mission is uncrewed, no astronaut will have the opportunity to bring an unauthorized sandwich along for the ride.