Let’s start with your childhood: where you were born and grew up, your family at that time, any brothers and sisters, what your parents did, and so forth. And, specifically, if there was anything about your youth that got you interested in what you eventually pursued as an avocation.

I grew up on a farm in rural Kansas: every day I fed the cows in the morning. Growing up felt very desolate. The nearest major town was Salina with a population at the time of 50,000. Wichita is the size of a normal small city but it was a thriving metropolis from my perspective.

My parents were not academics, my father was a farmer and my mother was a homemaker at the time, now she’s a counselor, she has a Ph.D., we both got our Ph.D.’s at roughly the same time! So, I really didn’t have a pedigree for doing science but it was something that was very easy to be drawn to.

But one advantage of growing up on a farm is that I could see the stars at night, clearly. I distinctly remember going to my grandparents’ house during Christmas, going along the road, and always seeing Orion. It got to the point where I memorized all the stars in Orion. It was very easy to get into astronomy because I was confronted with the universe in a very visceral way that would not have been possible if I had grown up in an urban area.

Beyond that, I think my route may have been atypical of the astronomers in my generation. I never watched Cosmos. Carl Sagan was never my hero. Instead, I was drawn by very matter-of-fact presentations of astronomy. One of my earliest memories was watching a PBS special on Voyager 2, seeing the spacecraft flyby Neptune. I thought that was really amazing that NASA could send a probe out that far. I remember seeing reports on the same program, not highly stylized, but very matter-of-fact, that other stars might have planets. The name of one of the stars they talked about was Beta Pictoris. Its Kuiper belt was then a new. Twenty years later, everything came full circle: I published two papers on Beta Pictoris, on imaging and characterizing its planet and its disc!

Interesting. Can I ask what your mother’s Ph.D. was in?

Counseling, dealing with at-risk populations.

Interesting, and we have a connection point already here, which is part of the reason for doing these, is for people to find connections with other interests and hobbies and talents that you have. Part of my growing up was on a farm in Idaho, and we had cows we milked and hay we bailed and all that kind of stuff and that added a dimension to my life that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. So, I identify with that. Do you have any siblings?

Yes, I have a brother. He is staying on the farm, now. He has taken it over, he’s raising his family there. I’m really the only one in my family who went on to do science. When I was a kid, I was very good at mathematics but I really didn’t know how to apply it. It actually took a long time for me to understand astronomy as something to which I could apply math.

I think I got into astronomy through the aesthetic beauty I found in the universe, then a little bit more for the philosophical implications of discoveries in astronomy, such as the Copernican revolution, with the big bang, evidence that possibly there may be life elsewhere in the universe. Those things were what really drew me. But the physics behind it, and the technology to do astronomy, and the mathematics, that all came later, very late. And really not until graduate school did I actually start to like physics, (laughs).

Often this interest doesn’t manifest until someone gets to college and has to choose a major. And it’s almost always something they are interested in, so it could obviously have started to evidence itself there. Was your undergraduate major in a STEM subject?

I had a very meandering path. When I was 11 or 12, I could tell you exactly how far away Rigel was; I could tell you how many moons Jupiter had and could name all of them. I could do all those things but although I went to good schools, they weren’t really equipped to teach the things I was interested in. They followed a more traditional curriculum of biology and some physics. So, my interest in astronomy kind of lay dormant for a long time. Instead, I actually got into athletics, tennis specifically, which was very bizarre for someone from a farm in Kansas. And I went to college purely with the intent of playing athletics. I only happened to take an introductory astronomy class in my first semester in college that reminded me that, “Oh yeah, by the way, I actually do like astronomy!” Not just simply that but there was actually a lot more to learn. And by the end of my first year, I actually gave up my full-ride Division I athletic scholarship and decided to do academics full-time. I experienced some real “growing pains”. I had to relearn calculus and fundamentally re-orient my mind in terms of what I focused my time on. While I was a little bit behind many of some of my peers’ advancement at first, I slowly caught up.

Was your Ph.D. in astrophysics?

Astronomy.

So, then there was a path that eventually led you to NASA Ames, and we always like to explore that so what were the connections or the drivers that had that result?

My path to Ames also meandering. I did my Ph.D. thesis work on the Spitzer Space Telescope, looking for indirect evidence of terrestrial planet formations, from studying dust around young stars. I had always been interested in trying to image planets but I felt like maybe the technology had not caught up yet to the point where we could really do that. Then a few months after I defended, we had the first direct images of planets around other stars and I realized that now the field was ready for this science. So I completely shifted focus. I started out doing direct imaging when I was at Goddard. And then really refocused my efforts with that when I was at Toronto and at the Subaru Telescope. Direct Imaging really kind of took over my life there.

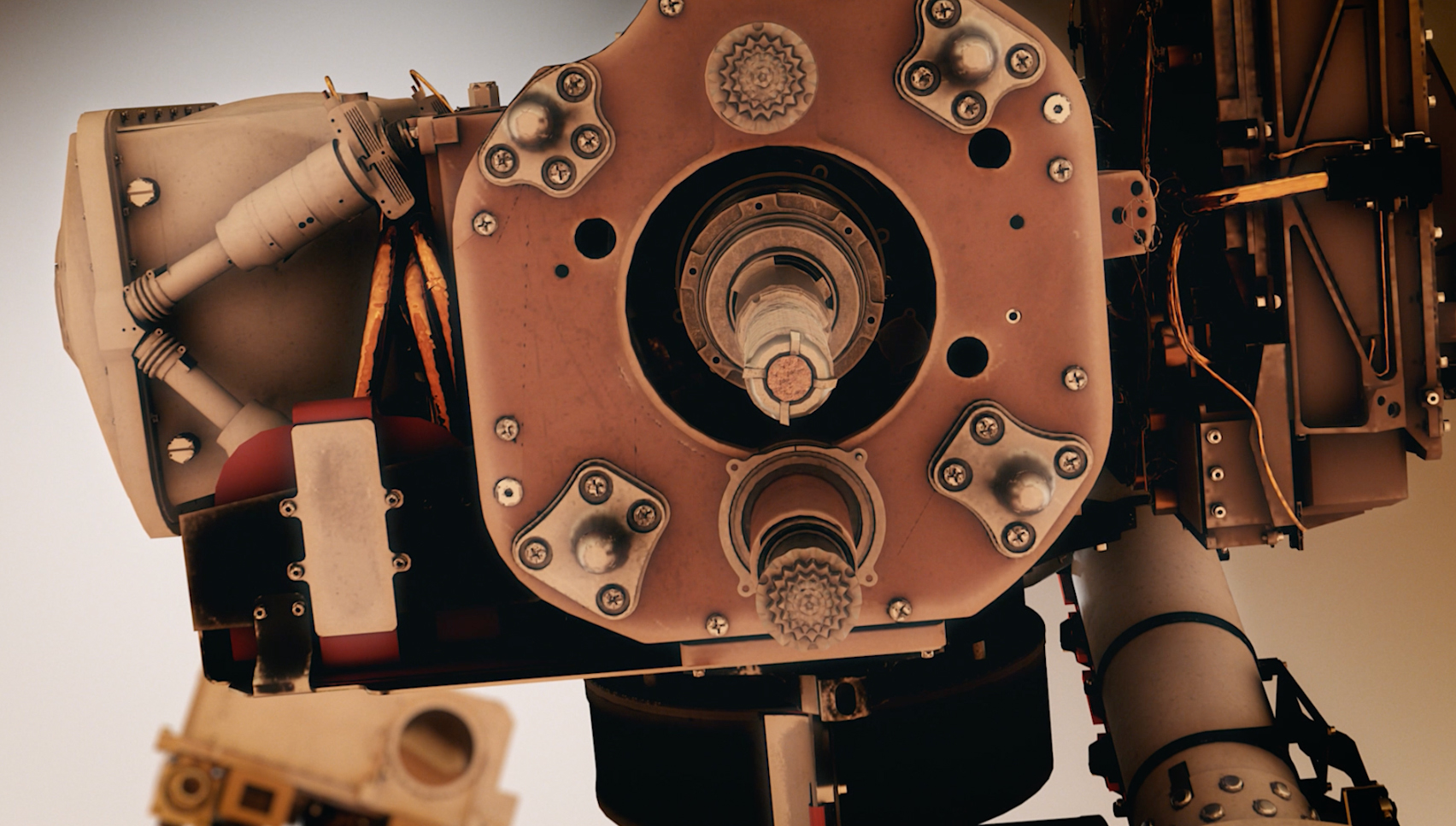

I think the connection with Ames was technology and instrumentation. It became very clear that there was a limit to what we could do right now in direct imaging without fundamental advances in technology. With the facility-class instruments that we had available, there was a very low ceiling for the kinds of systems that we could discover. We needed to develop new capabilities with instrumentation from the hardware side and also develop new software to be able to directly image planets that were up to this point inaccessible. And so that’s where Ames came in. My project focus shifted a little bit more into methods and instrumentation than what it was before, which was really pure science.

Was it a recognition of Ames’ work in developing these technologies or was it a personal contact with somebody here? You came out here on a postdoc, is that right?

My challenge was just a matter of being able to match up the kinds of advances that I thought were crucial and interesting, with the locations to be able to work on those technologies. Ames is known as being one of the centers for incubating some of these new technologies. The instrumentation focus project that I ended up doing at Ames had a very strong connection back to Subaru. There was a way to take our advances out of the lab, put them on an actual telescope, and test them on the sky to see if they work. That’s really been the aspect of the project that I’ve been doing the past year: ground truth testing on the sky of the techniques we’ve been honing in the laboratory environment.

And as you’ve done that, and we don’t want to make this the focus of the interview, but we’d like to understand the work that you’re doing, what you’re finding, what you’re trying to find, and why that’s important and why the taxpayer, who funds all of this, should want to make an investment in the kind of work that you’re doing?

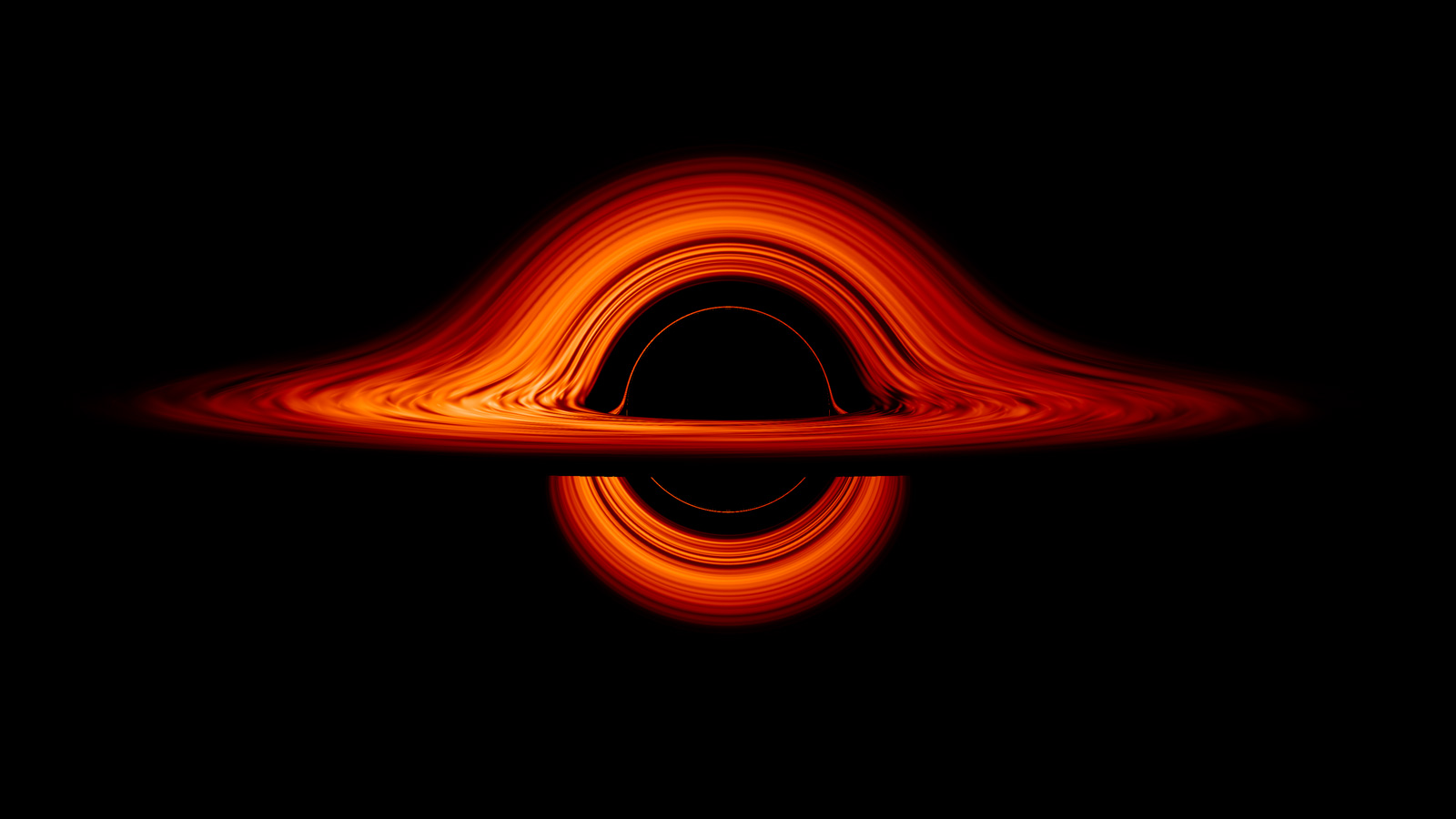

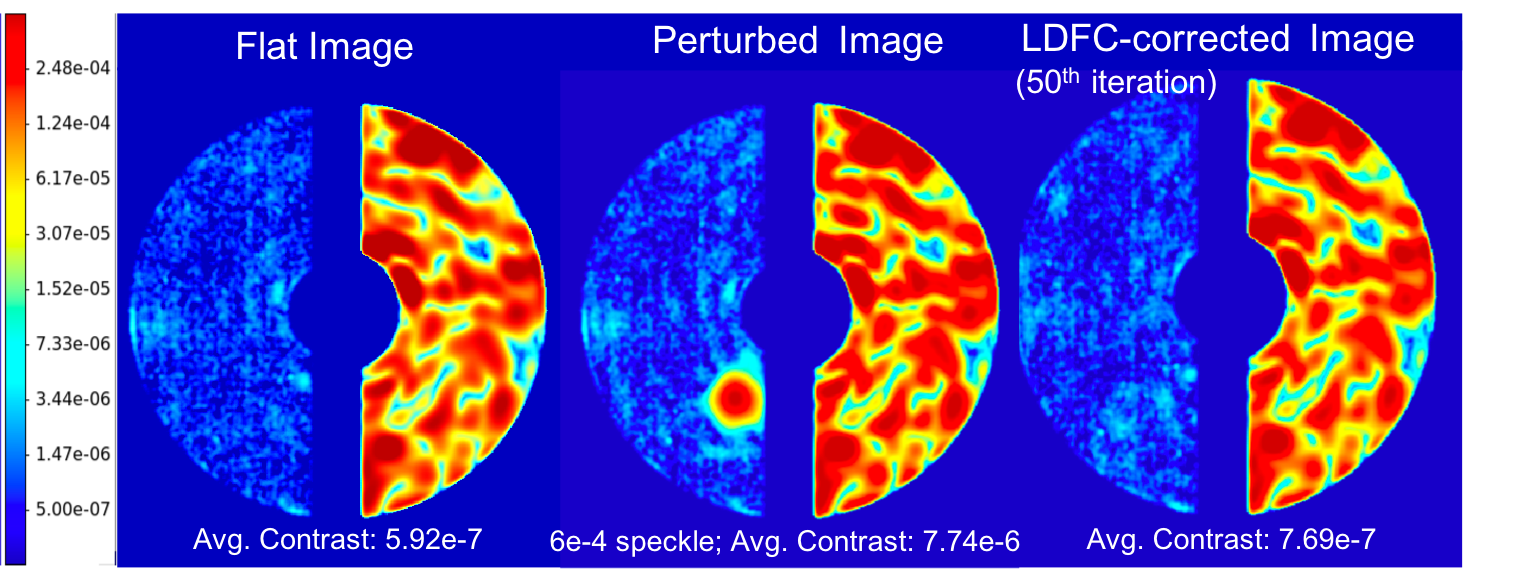

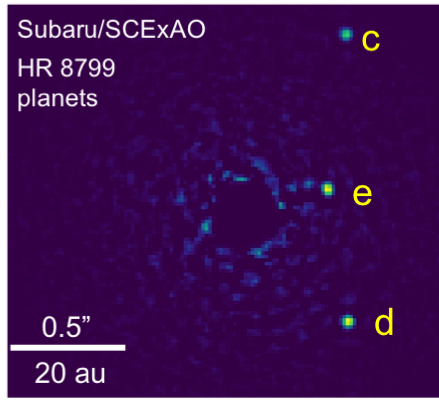

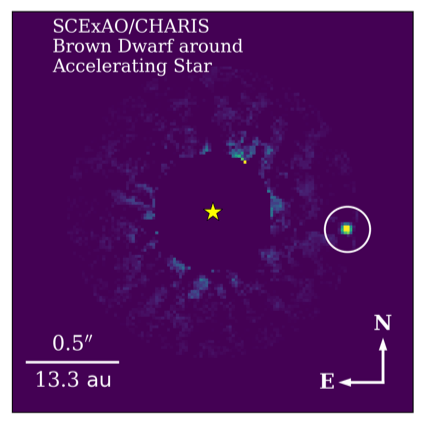

Right now, I have two focuses: one is mostly science and one is mostly instrumentation. The instrumentation work is on a technique called linear dark field control. It’s basically a way to be able to maintain very deep contrast images where we can see planets more easily. The problem is that we can configure our instruments to get extremely deep contrast, where we can see really faint things right next to stars, but maintaining that state of the camera where we record light from stars and planets, that’s really tough. And so, my focus has been on this technique that allows us to stabilize that good correction where we have a good capability of discovering planets. And on the science side, I carry out a direct imaging survey with the Subaru telescope, with some of the collaborators who are also involved with my linear dark field control project. This focus has been trying to directly image and then characterize the spectra of planets around nearby stars and be able to understand their clouds, chemistry, and gravity, and perhaps piece together their formation history.

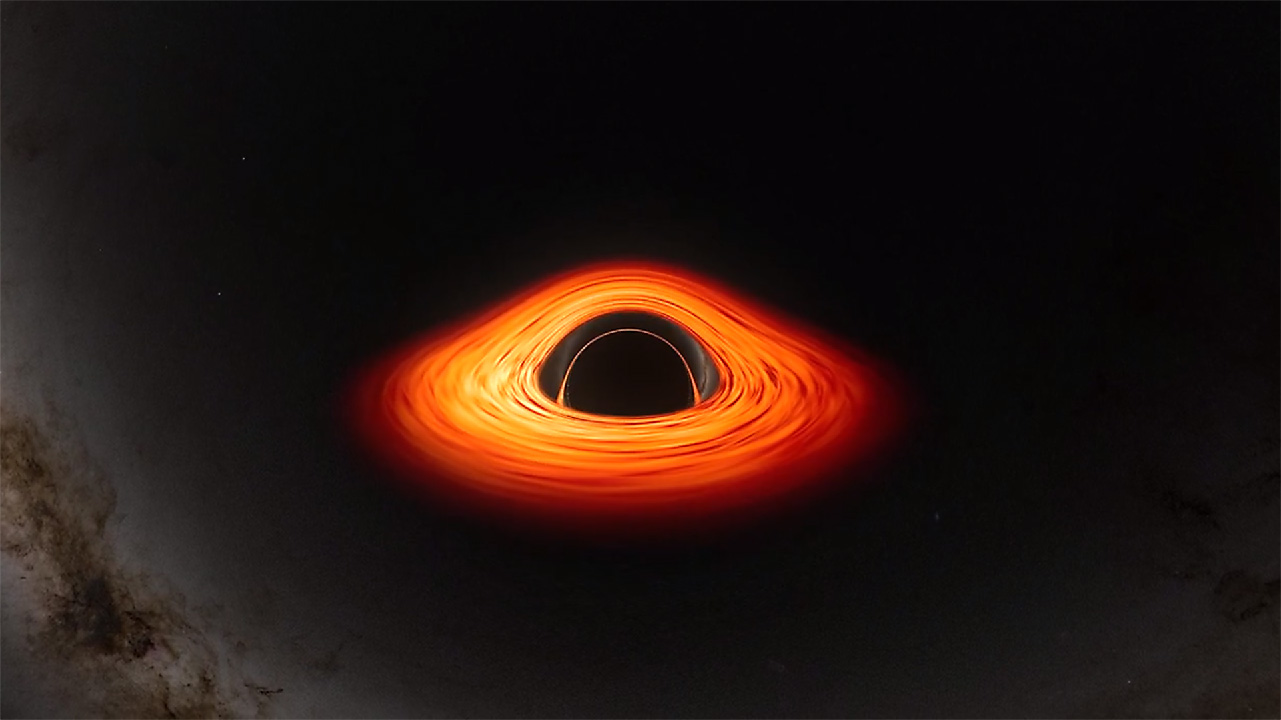

I think that long-term the way this fits in is that these instrumentation advances and science programs prepare us what we want to do about a decade or two from now with a NASA flagship mission: image an earth around a nearby star. Why this is goal important? I think astronomy is important because it probes fundamental philosophical questions and one of the most important is: are we alone in the universe? Is the earth rare? Or is the earth one of many life-bearing planets in our neighborhood? Direct imaging allows us to answer these questions.

Philosophers throughout history, not just in Greece or in Rome, but throughout the world have pondered these questions. There are examples in Afghanistan, and in China, throughout the Middle Ages, the people, leading thinkers, questioning whether or not the earth is unique and whether life is unique. These are not fundamentally scientific questions but rather fundamental human questions answerable by science. And hopefully, very soon we will have the privilege of being able to answer them.

This investment in astronomy bears many positive practical consequences. For those who work at the observatories, or at Ames, or at NASA, these are good high-paying tech jobs. There’s a lot of crossover in terms of the techniques to be able to do data science. Having a healthy, scientifically literate, technologically advanced country is something I very, very much care about as a patriot, as an American. In this sense, astronomy and NASA help us make the country better.

You’re speaking so eloquently that I hate to step in because you’re really making the case. And it is true. NASA enjoys tremendous public support, manifest through the budget for one thing. NASA always seems to fare well in the budget realm because of the popular support it has, which stems back to the public’s thirst for answers to these questions. That’s a great foundation to have and as you said, it’s a privilege to just be part of the search for answers to those great questions. Moving to a more practical focus, as you do this work, the question started out to be what is the typical day like for you, but because of the pandemic the days are kind of the same for everybody now, how has the pandemic affected you? Do you do most of your work remotely on the computer? Or is there a certain amount of lab or fieldwork that you do, it doesn’t seem like it to me but I’m not a scientist. How has the pandemic, the remote aspect of it, affected your work?

The pandemic has caused me to refocus my priorities and more fundamentally to re-strategize how I try to do the same kind of science. Because of the pandemic, we don’t have access to the labs at Ames. I do some laboratory work essentially using the exoplanet imaging instrument at Subaru, as my lab. I can remotely login to that machine and run the planet imaging system with sort of a synthetic star to test our new techniques. The pandemic has also refocused most of my effort on methods with data reduction and in doing the science program because for that part I don’t have to physically be at Ames. In practical terms what this has meant is that many times I will be staying up very late at night remotely observing from Subaru, or Keck on Mauna Kea. And that means I have to be very quiet and remember not to shout and wake up everybody else in the household (laughs). It has meant that maybe the work is a little bit more challenging since I’m not physically at some locations, I’m in my apartment the entire time. But I have not yet seen a significant drop in my ability to do research: I just have to keep a different kind of schedule.

Sure, and we’re blessed that’s the case, that we have tools that enable us to do things remotely because we’re not coal miners who can’t do their job unless they’re at the coal mine! You have a way to do these things. We also like to ask what are the things you like best and least about your job?

Well, I think the thing that I like best is just the excitement of knowing that you’ve discovered something that nobody else knows at that point. Like when you first see an image of a planet and nobody else has seen it before, and you think: “I can’t believe I’m seeing this for the first time anywhere!” Are you want to balance that excitement with not telling everybody that you found something. You don’t want to get scooped and also you want to be careful and respect the scientific process and be a diligent scientist. That’s the thing I like most about my job. The thing I like least about the job is the job climate is difficult, which means the career path is difficult. This is not an easy path, especially during your 20s. I had to live in the attic until I was 28 when I was doing my Ph.D. work! It means that you may have to delay starting things that many people see as fundamentally important to their lives like is raising a family, settling down, not moving. These are sacrifices you have to make. And that is a significant challenge and it’s one of the things I like the least about the job.

You have what I call the scientific mentality. A number of the interviewees we’ve had in this series have said almost exactly what you said about the fact that I can discover something that nobody else ever knew. The fact that I will know something before anyone else knows it. There’s something exciting in that notion.

What’s even more fun sometimes is that when you have done test after test and get to the point where you’re pretty sure you have discovered something, and you figure out have a lock on this discovery. I find myself wanting to let the public in on that excitement. Like when I give public talks, or talks at seminars, I’ll sort of hint at unpublished discoveries. I’ll show the images and then I’ll kind of whisper “Hey, I’ll let you in on a secret!” (laughs). That’s fun!

That’s cool! If you weren’t a research scientist, have you ever thought about what your dream job would be?

That’s really difficult because I think doing astronomy is such an integral part of who I am that I don’t know what that life would be like otherwise. I really don’t. It would be better to ask myself that when I was 18 or 19 before this path was set.

We have gotten a lot of responses to this question to the effect that “this is my dream job”! I’m living my dream job right now.” So, we understand that. What advice would you give to a young student starting out who would like to have a career like you are having?

I think there are a couple of things that come to mind. First, one of the broader ideas: dream big! Don’t believe that you’re not good enough or that you’re not smart enough, not capable enough, to be a part of the community that advances our understanding of the universe. Every single successful astronomer has a sort of “Imposter Syndrome”, or is prone to moments of self-doubt, and that’s good. If we didn’t do that as scientists if we didn’t have that humility to second-guess ourselves and check our results, the quality of our work would be far less. It’s healthy to have doubt. But don’t let the doubts themselves deter you. Work through them. And I think the other thing that’s important, and this applies to everything in life, is that you need to have a plan: a one-year plan, a two-year plan, a five-year plan. Things that matter in life usually are usually not just handed to you, and I believe that’s definitely true with science. Most discoveries are the result of a long carefully thought-out process. It’s hard work and it can be kind of ugly, and dirty, and meandering at times. Think through where you want to get to and work back to where you are and see what path you need to take to be able to do that. That’s sort of a general piece of advice but I think it’s applicable here.

That is excellent advice. We also like to touch on your home life your family, kids, pets, things like that, and I saw a little head poking out behind you a moment ago that I think belongs to a dog named Hubble, is that correct?

Yes, we have a dog named Hubble!

OK, and we’re going to meet him up close and personal. There!

He’s a golden retriever.

He’s gorgeous! Did you raise him from a puppy?

We got him when he was eight or ten weeks, in Los Angeles, and he’s coming up on three years now and the name came very naturally. It just sounded like a perfect name for a dog, especially a dog with an owner who is in astronomy. He’s a very sweet little guy, he’s always by my side when I’m observing late at night.

I was going to ask if he was company for you when you’re up observing at night?

Yes, he will stay up with me. He is my observing assistant!

And I saw a beautiful wedding picture of you posted on Facebook.

Yes, my wife does computational biology. She works at a company here in the Bay Area. She’s extremely smart and hard-working and during the pandemic, it has presented us with a few challenges, since we often have dueling telecons. So we have to balance our schedules else her coworkers get an earful about adaptive optics by accident. The one with the lower priority has to go in a different room and that’s usually me because my telecons are less structured. Hers are more part of an official team with a hierarchical company, so hers get priority and that’s totally fine.

So now, and I think this is my favorite question: what do you do for fun?

What do I do for fun? We enjoy hiking, so we go to Muir Wood’s, to Half Moon Bay a lot, we take the dog out, and sometimes we go to the beach. We just like to be outdoors. During the pandemic, I think we’ve sort of binge-watched everything! I’m a trekkie, and we’ve gone through the entire Star Trek canon now! Pre-pandemic we did like to travel a lot. We went to Bali, we went to China and Japan. I also have an interest in history: e.g. the US Civil War (and the Battle of Gettysburg in particular).

Well, you live in a beautiful part of the country to enjoy the outdoors.

Yes, and it’s very close to the airport also, and that’s another advantage of being near Ames, you have access to a hub for United and it’s easy to get around. And so, yeah, we do like to travel a lot. And because of astronomy, we go to Hawaii a lot. I’ve gone to Chile twice, with less success observing than in Hawaii. It’s a long flight but it’s also nice.

How about interest, hobbies, talents, musical instruments, that sort of thing? Sports? Do you still play tennis?

A lot of those things have kind of fallen away a little bit. A very long time ago I used to do electronic music DJ-ing when I was going to graduate school. I had a bit of the following but that’s kind of gone away. So, I did do that and I still remember how to do that. And I sort of vaguely remember how to play tennis. (laughs).

It’s like riding a bicycle, right?

A little bit, yeah.

So, is there an accomplishment in your young life, you’re still young, that you’re most proud of that is not related to your career? Or is that yet to come?

Yes, that’s yet to come.

Then let us ask who or what inspires you? You were not a Carl Sagan devotee.

Yeah, I was not a Carl Sagan devotee, at all. And I was before Neil deGrasse Tyson became popular. I don’t feel that I necessarily need other astronomers to inspire me. I think the universe by itself it’s good enough. Just from contemplating the universe as it is and what little we’ve learned about it, I feel inspired. If anything, I feel a little bit upset knowing that we don’t know more about the universe and that during my lifetime there will still be fundamental things about the universe that we don’t know. I’m impatient. So, I want to learn as much about the universe as possible.

That’s a beautiful answer. What could be more inspiring than looking up at the heavens and wondering about these deep questions?

Yes, you are confronted by infinity and nothing at the same time.

That is amazing! At this point maybe we can turn the tables and ask if there was something you wish we had asked you that we didn’t?

I think we kind of covered it, actually.

Then we thank you for taking a moment from your busy schedule to chat with us.

Thank you very much. Ames would not function without the hard work of many people and I’m very privileged to be able to work with you on many things over the past few years, without which I’d be in serious trouble! (laughs). So, thank you very much for getting this setup.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 9/21/21 virtually.