A conversation with Madhulika Guhathakurta, lead program scientist for new initiatives in the Exploration Technology Directorate at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, and the lead scientist for the 2017 total solar eclipse.

Transcript

Host (Matthew Buffington):Welcome to the NASA in Silicon Valley podcast, episode 55. This year on August 21st, for the first time in 99 years, a total solar eclipse will make its way across the United States. A remarkable solar experience of a lifetime. Luckily for us here at Ames, we have the advantage of learning first-hand about what the Sun means to our solar system and beyond from NASA’s lead scientist for the 2017 total solar eclipse, Dr. Madhulika Guhathakurta. Better known as Lika, Lika has spent most of her career researching the Sun and its significant influence on Earth. Along this journey, she has had the opportunity to work as a scientist and mission designer while also managing multiple science programs over the years. Here to talk to us about this year’s total solar eclipse and more, Dr. Madhulika Guhathakurta.

[Music]

Matthew Buffington: Tell us a little about yourself. How did you end up at NASA? And also how did you end up in Silicon Valley? Because I know for you those are two different stories, especially coming from Goddard.

Lika Guhathakurta: Well, they are. I was in Boulder. I was a graduate student in Boulder. I came from India, came to Colorado. I had a fellowship at High Altitude Observatory NCAR, and then I became a post-doc at Colorado University at LASP. So, I spent a total of 13 years in that area, and then it was an issue of finding two jobs, you know, two body problem. My husband is a mathematician so we moved to the Washington, D.C. area where I had a job at Goddard Space Flight Center, and I was a research scientist there.

But that was only for five years that I was at Goddard, which is where a lot of ideas of connecting Sun and Earth sort of started. I did research and flew payloads on Spartan missions, Spartan 201, five of those. These were free-flying payloads that mission specialists, astronauts, would actually deploy to collect observations of the Sun, the kind that we will see during the eclipse. So I was a project scientist on White Light Coronagraph, one of the two instruments. You know, it’s kind of interesting how one of our own from NASA Ames, Kalpana Chawla, was the mission specialist in ’94.

Host: This is an astronaut who had started off at NASA Ames.

Lika Guhathakurta: That’s correct.

Host: So, go back a little bit more. I’m trying to imagine a five-year-old Lika in India looking up at the stars thinking, one day I’m going to start studying space. How did you get from that point Colorado? Were you always interested in science? Did your family encourage this? Tell us how you got to Colorado.

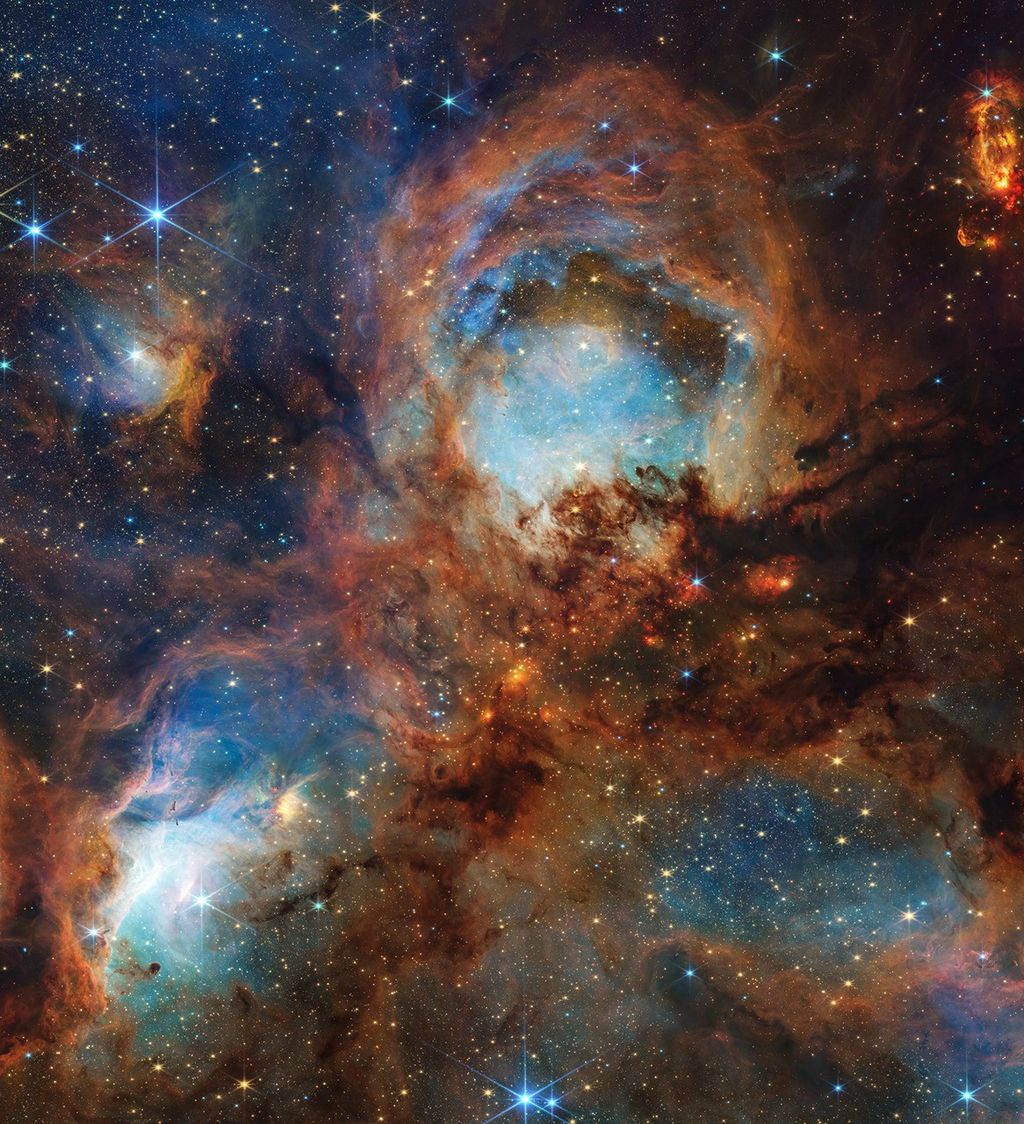

Lika Guhathakurta: I was always interested in nature, the night sky in particular, stars in particular. Who isn’t? You look at the stars and the first question that comes to mind, you know, where did they come from? What are these things? Where did we come from? These are big questions for NASA, right? But even a child thinks about that actually because these are quintessential human questions.

Host: Exactly. They’re human questions, not just NASA questions, we’re just fortunate to get to work on them.

Lika Guhathakurta: Fascinating, right. So I was always fascinated by stars. It’s still fascinating to me. I just came from a camping trip in the mountains and it’s still mesmerizing. We know so much about them that you would think that that romanticism would go away. It doesn’t. Thank God for that. I am still blown away being able to see the white Milky Way away from city lights.

Host: How early in your studies, or in your career, did you start thinking, okay, here’s this big interest in stars, then narrowing it down to, oh, I have a favorite star, which is also happens to be the closest star to us, studying the Sun.

Lika Guhathakurta: I know, and the way I see it, the only star that counts.

Host: The only star that counts.

Lika Guhathakurta: It really upsets astronomers and astrophysicists. You know, Sun not only takes away twelve hours of their observing time, but then I say it’s the only star that counts. Seriously. This is the only planet we know where there’s life.

Host: And it’s the only star that provides power to a lot of those space telescopes.

Lika Guhathakurta: Exactly.

Host: Because without the solar power they wouldn’t work.

Lika Guhathakurta: Everything, everything. I mean if you go deep down into it, I say it jokingly, but it’s also true.

Host: Like, “kidding, not kidding.”

Lika Guhathakurta: Exactly.

Host: In your studies in school did you move to more the heliophysics, the study of the Sun?

Lika Guhathakurta: There was no “heliophysics” even as a concept when I went to school. So, what I did for my master’s in India was astrophysics and general theory of relativity. As a matter of fact, I was concentrating more on general theory of relativity and particle physics. That’s kind of where the meat of theoretical physics was. And this is late 1970’s, 1980 I’m talking about, a long time ago. We have made so much more advancement in the area. Then, when I came to this country, my goal still was to pursue general theory of relativity, astrophysics. Those were my broad goals.

So I came to University of Denver. When I came there, the two professors that were in astrophysics went on sabbatical and as a result, I had to work on another area. That was actually atmospheric physics, but analyzing solar carbon monoxide lines. I used to run these really big, massive codes on NCAR Cray computers at NCAR. I was not really that interested in the topic, and I came across this call for fellowship in solar physics at High Altitude Observatory. I applied and I got in.

Host: That’s the beginning.

Lika Guhathakurta: That was the beginning of my effort on applying all of my knowledge of astrophysics to the Sun as a star.

Host: Then after working in that for a while, when you went to the Goddard Space Flight Center, one of the NASA centers, over in Maryland, was it still working on heliophysics, or was it still working on the Sun, or something completely different?

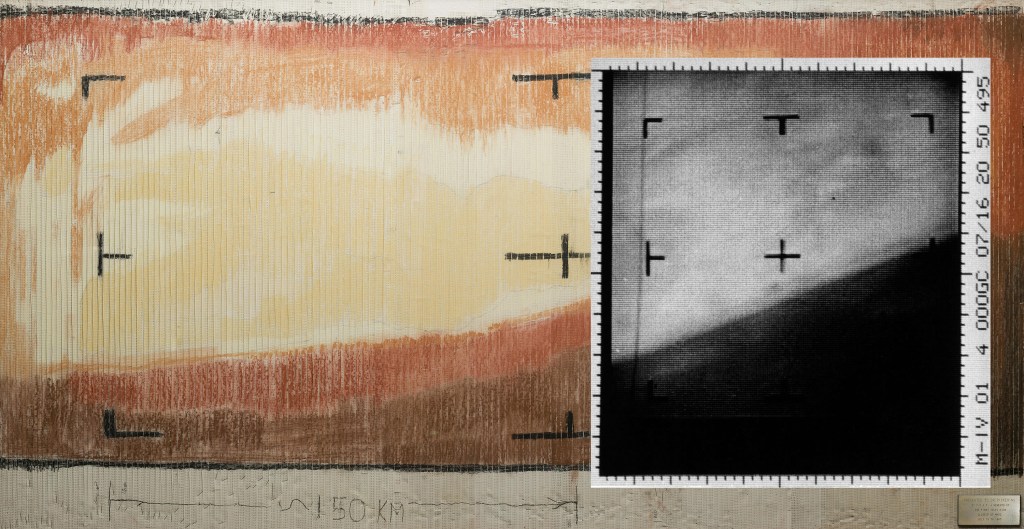

Lika Guhathakurta: Heliophysics was still not there. What I was doing then was Sun as a star. You know what I was looking at – this is something I have to tell because this is so cool in the context of what’s just going to happen almost a month from now, the total solar eclipse. My thesis picture was in Time magazine in 1988. And the picture was a picture of the white light corona, eclipsed corona, taken by scientists at the High Altitude Observatory. This is, I think, from the Philippines in 1988. Superimposed on that, on the black disc of the Sun was a soft X-ray rocket image, and this was the first of its kind.

Today our telescopes are producing these dime-a-dozen. That was the first picture showing the soft X-ray view of the corona on the disc and the white light. That’s kind of what I was studying. I was connecting the surface of the Sun to corona. The fact that that corona blows out all the way into the solar system, you know, we kind of knew that, but that science wasn’t that robust. People were pursuing it separately. We used to call it heliospheric physics, and we use to call it solar physics.

The heliospheric people just did the heliospheric part, measuring particles, magnetic field, all of that. Near Earth, or near another planet, like Voyager spacecraft, like ACE, Advanced Composition Explorer. But they were not working with solar physicists. I was trying to make that connection. So, that kind of began – that approach began with my thesis. When I came to Goddard I kind of cinched that even more. I was working on the Spartan mission where we were getting data, white light data, which is the expanding corona, from the Spartan mission, and then we had the Ulysses mission going on, which actually went over the poles, but it didn’t have any imaging instrument, it collected data.

I was trying to connect the Sun to what Ulysses was observing, and brought together people from the heliospheric community and solar physics community. That began the Sun/heliospheric connection. It still wasn’t the Sun/Earth connection. There is a connection to Earth. That happened after I went to headquarters. In 1998, I went to headquarters. I was invited to go there and do the STEREO mission. The STEREO mission essentially had these two spacecraft that are, they’re still doing it, going sort of in an Earth-like orbit, one a little ahead, one a little behind Earth, and gave us the first three-dimensional view of the Sun, and then the first view of the far side of the Sun. It is quite amazing.

While I was at headquarters doing the STEREO mission, our division director, Dan, came up with this concept of a program called Living With a Star. Living With a Star is sort of the program that really sort of ushered us, in 2005 I would say, into the field of heliophysics. And Living With a Star, I’ve been the program scientist from its very inception through 2015, is the [unintelligible] of being, you know you’re looking at those kinds of signs that are relevant to life and society. So it’s not just curiosity-driven science only. It’s not just science for science sake. It science for science sake, but that intersection that also have tremendous application to life here on Earth.

Host: Talk a little bit about working at Goddard. You’re now here over at Ames, and you were here before. In fact, I think it was about a year ago we met in the cafeteria waiting in line on burrito day or something. Talk a little bit about that, of how it is that you ended up landing over here at Ames, and working on some of this stuff and how that fits.

Lika Guhathakurta: I had spent 15 years working on Living With a Star program at NASA Headquarters, creating many different missions. Solar Dynamics Observatory, Van Allen Probes, Solar Probe Plus, which we just renamed to Parker Solar Probe, Solar Orbiter collaboration with European space agencies, many others. Created international community called International Living With a Star where all the space agencies became part of it to cooperate and collaborate on this single concept, the Sun/Earth, Sun/planet connection. Worked with United Nations Committee on peaceful uses of outer space to create space weather as a permanent agenda item there.

These things were kind of done and I think I was itchy for something new. I was always interested in detail at Ames for a long time, but there wasn’t any convenient moment to do that because I was still so heavily involved in so many of these missions. So when Solar Probe got confirmed, that was a very good time. I came for half a year and what drew me to this place is the connection to the Silicon Valley, the entrepreneurial mind. It’s a different –

Host: A different mindset from a typical bureaucracy, or even international affairs.

Lika Guhathakurta: Completely. And I’m very drawn to that because even in my bureaucratic job I think what I have done is tried to create something out of it. Ames also has a real interesting discipline areas that I, in my mind, can already see connecting them. So this new detail for one year, the lead program scientist for new initiatives in the exploration technology directorate. It’s not just specific to that directorate. I’m really looking at cross-cutting ideas.

Host: Yeah, it’s one of those really fascinating things. Ames has this very broad, diverse portfolio, but that’s the cool thing is when you have autonomous systems that interact with small satellites that interact with supercomputing, or Earth science, or space science, or even space biology, like ISS stuff. It’s like, there’s weird interconnectivity where all of these seemingly different fields can cross and intersect where, I think normally if you only focus on one of those, you can kind of miss some of those opportunities.

Lika Guhathakurta: You said it so beautifully.

Host: I’ve been practicing over several episodes.

Lika Guhathakurta: In fact, one of the ideas and projects I have in mind actually will be brining all of those together, so let me tell you. I’m planning to host a workshop in late October or early November really to kind of take stock of our current knowledge of the radiation in environment in deep space and also in aviation altitude. If you want to be explorers and go beyond low-Earth orbit, we have to tackle this problem.

But even in aviation altitude we tackle this problem and we don’t know the answers very well. We know the answers from one or two satellites. My goal is really to take stock of what is the state of instrumentation and development in that area. What is the state of the modeling, you know, transport of particles and generation of radiation? And finally, how do we kind of create a platform for distributed approach to collecting radiation.

You talked about small sat, you talked about supercomputing, right, that’s kind of the modeling world. You talked about space biology, that’s the biological end of radiation. Radiation effects hardware as well as people. That is also the same kind of phenomenon also is percolated into the aviation altitude, especially for high altitude, if you do space tourism. But this is an area, again, I hope I’ll be able to work with the aeronautics division here. Really you can take one idea and you can just branch out.

Host: One thing that we’d be remiss to mention is, looking especially in, of all the fields and the workshops and stuff that you’re working on, but of course the big thing coming in, you have the super bowl of heliophysics, which is even more important than the super bowl because it doesn’t happen every year, but we have this big eclipse, the 2017 eclipse come on. This is breaking the fourth wall of the podcast magic, we’re actually recording this at the end of July. We will release this podcast August 17th, so right before the eclipse is going to happen.

For somebody who has been studying this, you have to be feeling super hyped, and you also have to be really excited as it builds. What’s going through your mind? What are you preparing for? What are you looking at as you get ready for this huge eclipse that’s going to cover the entire United States.

Lika Guhathakurta: I don’t know that there’s any one word or sentence that really captures my sentiments. I am in this hyped state and I think it will remained sustained for the duration. What is absolutely joyful, and it’s almost close to a month before, that I am seeing that the country, the reporters, are getting engaged in communicating this. This is such a potential moment, I would say – I’m going to use big words because that’s how I feel. You can’t predict these things, but that’s how I feel. It’s an event of history.

Host: Absolutely.

Lika Guhathakurta: Where the entire population of America, including Hawaii and Alaska, can view a partial solar eclipse. You don’t have to do anything, you just need protective glasses, and you can be wherever you are and look up at the sky. The only thing that will prevent you from seeing this directly looking at the sky is if you don’t have protective eye cover. But even then you can project it. The other thing is if it’s cloud cover. Otherwise, everyone, wherever you are, you can observe this.

People who are on those 14 states, about 70 miles wide, the special path, called the path of totality, that is a transformative moment. I kid you not. I’m a scientist, you know? Keep that in mind. And a solar scientist at that, but nothing takes away from when you actually look at the eclipse. The corona, the shimmering, pearly halo breathing. And It’s dynamic, you can see sometimes the post flare loops, the structures move.

You’re seeing this with your naked eyes. You’re seeing the outer atmosphere of the Sun, and we live in that atmosphere. We don’t think about it, but when you see it, somehow you begin to sense that. For me, if human beings understand that, there are so many greater things we could do together.

Host: Wow. Yeah, it reminds me of – A lot of people from Ames are going to be over in Oregon. In fact, you’re going to be heading up to Oregon as well to watch this. NASA TV is doing a huge production that will last throughout the duration of the totality at different locations throughout the day. But we have this drawing up on our whiteboard in our office where it says, I think, an 80 percent of eclipse, and it was making that emphasis of, yeah, the total eclipse will be up in Oregon, but we’re still going to get 80 percent. It was still really cool.

So for the folks who are not necessarily in the path of the totality, you’re still going to get quite the show.

Lika Guhathakurta: Imagine, most people have never seen an eclipsed Sun, whether partial or total. I mean this is such a cosmic coincidence. With the population that we have in the country, with the technology – This happened 99 years ago, but think of our knowledge base today, think of social media, think of all the technology, all the apps, the cameras, the lens. The kind of observations we are going to be able to take – I’m not even talking about the science observations which NASA will be doing from our operating spacecraft, from the ground, from airplanes, from balloons. You name it and we are doing it.

But then there’s the other side. There are animals, you can actually do animal behavior. There will be cameras in zoos. Animals respond to the change in ambient light. You know, social behavior, psychological behavior, it’s really quite an incredible moment.

Host: In talking about it being impactful for everybody, one of the coolest things that I saw was a project that’s coming out of Ames, but it’s actually with the SSERVI group – we’ve done podcast interviews with different folks from SSERVI here before. But talk a little about this, it’s an actual braille book about the total eclipse. If you’re visually impaired, you’re not going to be able to see the eclipse, but NASA worked with them to create a book where you can feel it with your hands and it’s a whole detailed thing of how the totality works, where it’s going to go across the United States. So, talk a little bit about that.

Lika Guhathakurta: It’s really quite amazing, the steps that NASA will take to make this accessible to almost all, even the ones who are visually impaired. Through tactile sense you kind of get that imagination of what’s happening, what’s the phenomenon like. We have done this for the eclipse for them to be part of it and understand what’s going on. We have done this with other missions actually. We do it through braille. Sometimes we produce music out of the data we collect. In the deep space, where we think space is empty, and it’s not. We measure the particles and then we actually give them some tonality as opposed to a color. That’s also something we do in Hubble images, for example.

NASA is really, in that sense, very thoughtful in sort of making what we are doing as accessible to everyone as possible. I think this is such a cool thing.

Host: Talk a little bit about what are your next steps? What are you getting ready for? People are going to be listening to this the Thursday before the eclipse actually happens. What is some advice? What do you want to tell people? Get some glasses.

Lika Guhathakurta: Absolutely. So, let me kind of, I want to go back a little bit. In 2015, when I went back to NASA Headquarters from Ames, after doing half a year stint here, I was given the charge, they said, “Lika, you are going to lead the eclipse event of 2017?” I said, “What the heck does that mean?” I mean, this is nature’s eclipse, and we are blessed to be here and having the show in our backyard. What is NASA going to be able to do?

There was outreach, engagement, all that going on. I’m thinking, how do we bring that added NASA value with science and all of that? And it took me three or four months to kind of figure out that we use NASA as a bully pulpit basically to talk about all our science. Eclipse science has happened for centuries with many discoveries in the past, very important. Exoplanet, for example. You know, the way we observed the first exoplanet is actually a phenomenon of eclipse.

Host: Yeah, the transit method is an eclipse.

Lika Guhathakurta: Exactly. So we have such an opportunity to teach everyone that eclipses are predicted through physics. It’s the science, it’s the math. Because there are lots of people who don’t believe that these are actually scientific phenomenon. So this became kind of a goal. This is a huge way to educate people about all the science we do. You know, the general theory of relativity was verified through –

Host: Mm-hmm, was verified – Einstein, during an eclipse, they could see the star.

Lika Guhathakurta: So there is no science that’s kind of untouched by the eclipse. The Moon, it’s the Moon’s shadow. LRO, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, has given us such exquisite data with which folks at Goddard visualization have created the umbral shadow, and we didn’t have anything like that before. The umbral shadow used to be a circle before, and now it’s a polygon because it takes account the topography of the Moon, where the mountains and valleys are. As the shadow moves through the USA, you can see it interacting with the topography of our planet, our mountains and valleys, and you’ll see the shape change. It’s fascinating.

You’re learning science even as you’re doing prediction of the eclipse. We are constantly refining this. So finally, what I want to say, this was audacious task. I have helped kind of bring this connectedness to the interdisciplinary science for the eclipse, but it was still the question, how do you get to touch everyone, inform everyone, right? I think the United States Postal Service came up, with one swoop, solved that problem. Think of any agency that really, literally touches everyone.

Host: Exactly. Door to door.

Lika Guhathakurta: Door to door. So when they approached us last year that they wanted to create an eclipse stamp, and you know I participated in that event, and worked with them. And then the unveiling of the fabulous stamp, first ever kind of “forever” stamp. It’s a thermochromic stamp with the eclipse image with a dark center. Then, if you put your body heat into the dark region, then it transforms and gives you the topography of the Moon. That’s a stamp. That is within reach for everyone in America.

So you can see how agencies have come together to kind of celebrate this moment. I’m pretty happy.

Host: Okay, we’re looking at the eclipse and how that interacts with the Moon and stuff, but talk a little bit about probes, Solar Probes, stuff like that, that are going to also, not just learning about the Sun through an eclipse, but actually going there, seeing for itself.

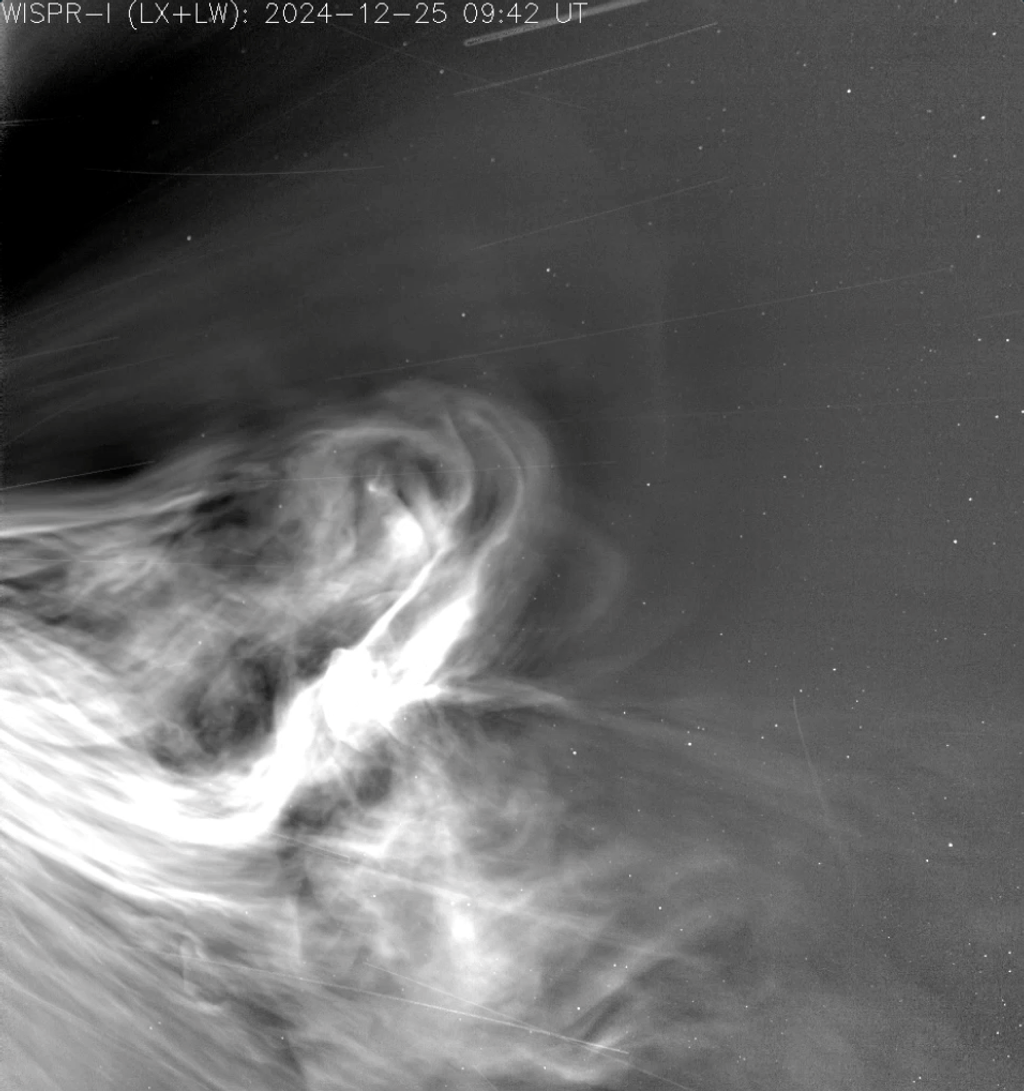

Lika Guhathakurta: So, eclipse is a cosmic phenomenon. Nature created it. We just are incredibly lucky to be able to witness this. What an eclipse does is gives us a view very close to the corona, so we can’t actually have that view any other way, not even from our telescopes in space. The Moon is a perfect occulter and does not scatter light or anything, so it’s ideal.

Now, you know, human ingenuity just doesn’t stop with nature providing us with an opportunity. We create our own. That’s the story of Solar Probe Plus, which has just been renamed to Parker Solar Probe to honor Eugene Parker who really kind of discovered the phenomenon of solar wind way, way back. This mission, literally, a year from now, between July and August of 2018, is going to go touch the Sun.

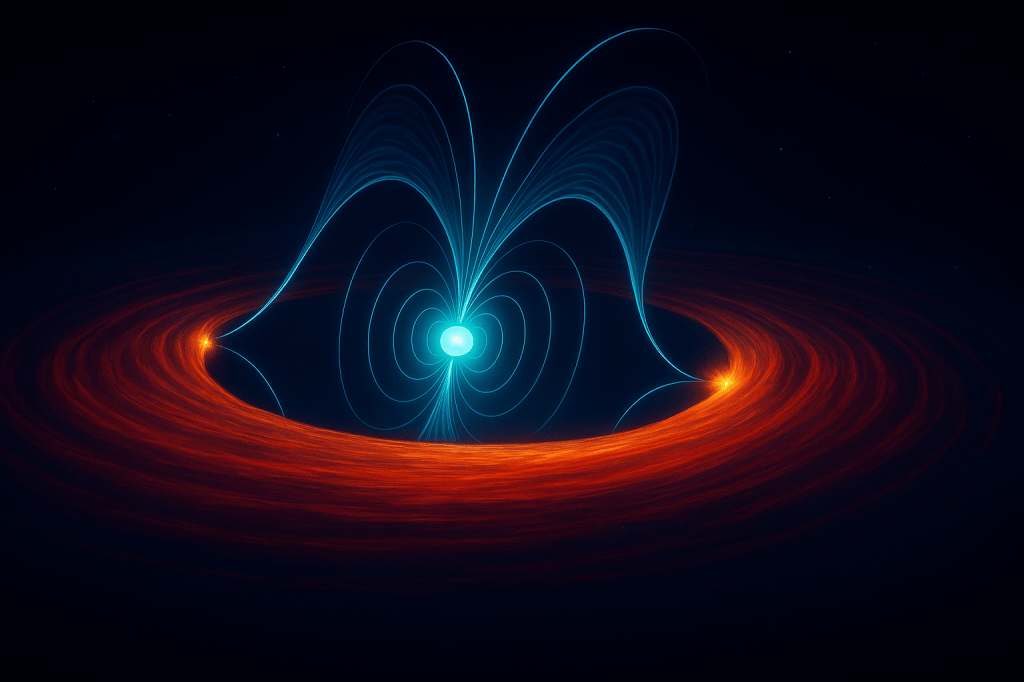

So, the eclipse corona that we will see in the path of totality, the Parker Solar Probe will actually go to that environment to measure locally the conditions of the corona so that we can really answer some of the most pressing questions not only of heliophysics, I think of astrophysics, of physics in general. The two questions are, when you look at the Sun, the yellow ball that we look at, the temperature of that surface, compared to the corona, the corona is much, much hotter than the photosphere of the Sun. The corona is millions of degrees.

Common sense kind of suggests that if you move away from a source of fire, the temperature should go down. In this case it’s kind of going up dramatically. So, question number one, what heats the corona? Even though we have, theoretically, and from remote sensing observations, have ideas, you know, that maybe deposition of magnetic waves, sound waves. Lots of different ideas, but we still don’t know. Because locally we haven’t been able to measure it. It’s all sort of remote sensing observations and theoretical ideas.

Host: Let me clarify this because this is a thing that’s like, I’m feeling my mind being blown. It’s like, obviously the Sun is very hot. There’s nuclear explosions inside.

Lika Guhathakurta: Inside, deep in the core.

Host: In the core. What you’re saying is, as you get away from the Sun it’s hot, obviously. But you’re saying that at some points when you get further from the Sun it actually increases in temperature?

Lika Guhathakurta: Yes.

Host: That’s insane.

Lika Guhathakurta: You are absolutely right. So, there’s the radiative zone, the core, where you have fusion which actually generates the heat. It takes a long time for that to propagate out. So the temperature is gradually decreasing until it gets to the photosphere.

Host: That makes sense. There’s a flame, you get away.

Lika Guhathakurta: Yeah, yeah. And until you get to the photosphere that’s what we’re looking at. Then the part that we normally can’t see with our naked eyes, the corona, when you get to the corona, the outermost atmosphere of the Sun, all of a sudden it increases in temperature, dramatically.

Host: Oh wow. That’s weird.

Lika Guhathakurta: That’s a mystery, a puzzle, and an important science question. That’s one. The second question is that the corona is not static. The corona is full of particles. We call them in plasma state where the ions have electrons stripped away, so you have electrons, protons, ions, and they are escaping the pull, the gravity of the Sun and blowing out. We call this solar wind. The wind can be gusty or it can be slow, or breezy, or stormy, to borrow terrestrial weather kind of words.

The question is, again, something has to put energy into the system for the solar wind to accelerate. These are very important questions. But they are not only important questions that we want to answer from a curiosity point of view, this is also the region where space weather phenomenon is born. We live in this atmosphere. These charged particles interact with out satellites, create radiation for our astronauts, or high altitude passengers, or creates the aurora light show, or creates transformer failure. Any number of things.

The impact of these conditions on our technology is the phenomenon of space weather. If we understand this better we can do better predictions, and therefore people can take, operators of various things can take mitigating steps.

Host: So, for folks who are listening, who are looking, who are getting ready, getting hype, ready for the eclipse, what we’ll do is we’ll put all of the NASA.gov links and websites in the show notes so people can just go sit there, click on that for more information on the eclipse. But then also for the live coverage that will happen at NASA TV. And you will see Lika at the Ames portion over in Oregon live as it’s happening. And we’re all keeping our fingers crossed for bright, clear skies so that we can get the best view.

Lika Guhathakurta: Exactly.

Host: So anybody listening, if you have any questions for Lika, we are on Twitter @NASAAmes, we use the hashtag #NASASiliconValley. Go ahead and feel free to send us some questions and we’ll get back to Lika because it looks like you have a lot more exciting stuff even happening into October and as it goes into your workshop.

Thank you so much for coming over. This has been way fun.

Lika Guhathakurta: Thank you Matt.

[End]