A conversation with Jack Boyd, Senior Advisor to the Center Director at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley.

Transcript

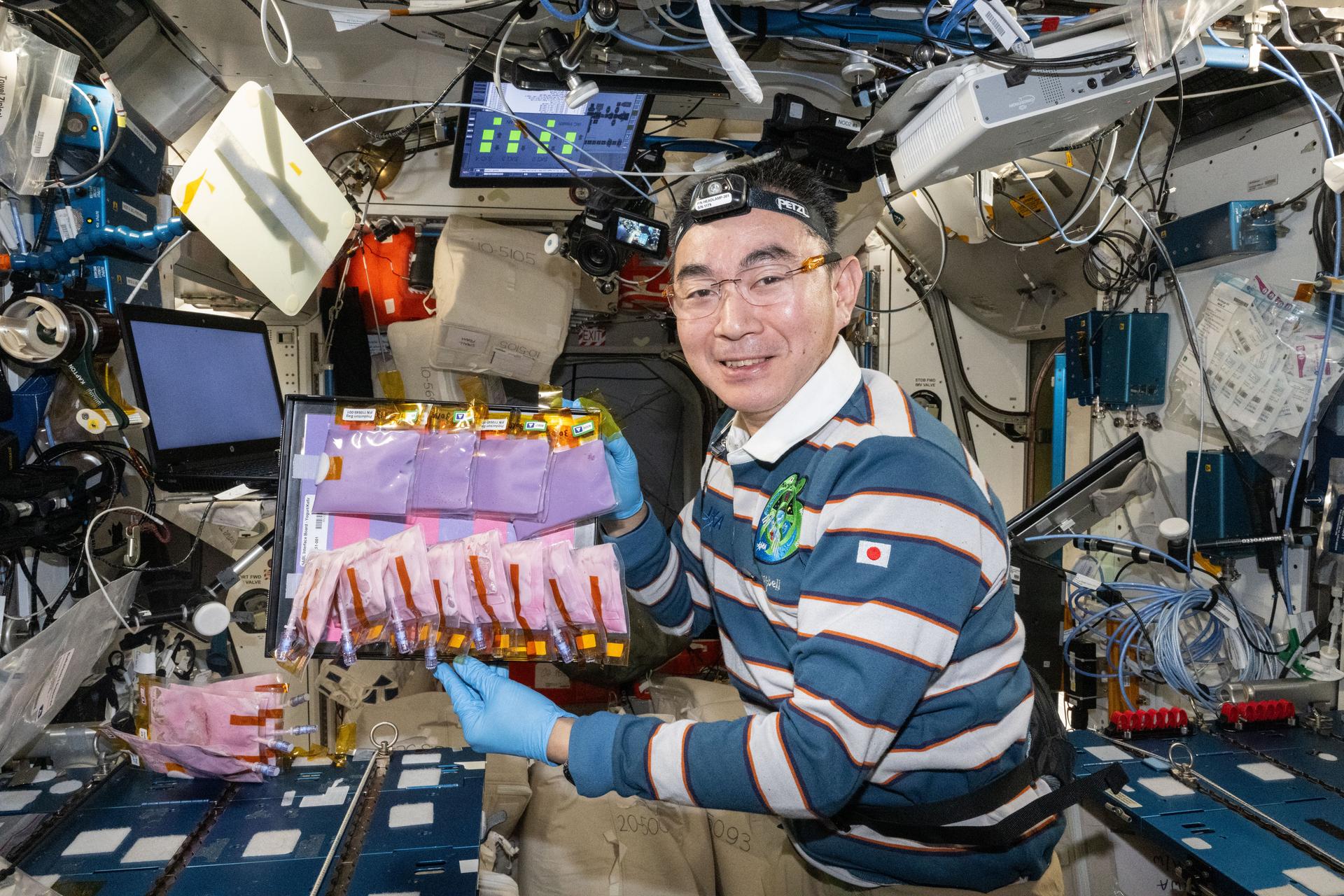

Matthew Buffington (Host):You are listening to the 50th episode of the NASA in Silicon Valley podcast. As a special treat, we want to give a plug to our friends down at the Johnson Space Center for a new podcast that they just launched called, Houston, We Have a Podcast. Their first episode is a great overview of the International Space Station and their next upcoming episode showcases NASA’s new astronaut class. Their link is in the show notes but you can also catch them and the NASA in Silicon Valley podcast on NASA Casts, which is one single omnibus podcast feed that includes all of NASA’s podcasts into one big rss feed.

Today’s guest is Jack Boyd, Senior Advisor to the Center Director at NASA Ames. Jack has 70 years of experience at Ames, first joining back in 1947 when Ames was a part of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). This is fitting as NASA’s Langley Research Center is celebrating their 100-year anniversary. In fact, if you are in the Virginia area, you should check out Langley’s Centennial Symposium that runs till Friday. Jack talks about how Ames spun out of Langley during the NACA days and how they laid the groundwork for modern aviation. We talk about how NASA was created, pulling in the NACA centers, and how NASA continues to be with you when you fly. So, here is Jack Boyd.

[Music]

Host:We always like to start off this with getting to know the guest a little bit, where they talk about how they joined NASA, how they got Silicon Valley.

Jack Boyd:NACA.

Host: Yes. I was going to say, this is like a little bit of a unique situation for you because you joined NACA and this wasn’t even called Silicon Valley when you moved out here.

Jack Boyd:No. It didn’t become Silicon Valley for, what, probably 10 years after I got here.

Host: Oh, really?

Jack Boyd:Yeah.

Host: So talking about NACA, how did you end up working at Ames to begin with?

Jack Boyd:I’ll go way back to Virginia. I was born in Virginia.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And I was interested in airplanes, but I was more interested in, not sports, but in doing things with my hands.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:Building stuff.

Host: Kind of tinkering and building.

Jack Boyd:And I lost track of that very quickly, though. But I had a cousin who was a parachuter.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And he came back from the war and said, “I’m going to go to Virginia Tech [Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University]. You ought to come up there and be an aero engineer.” And I said, “What does an aero engineer do?” He said, “Well, I’ll show you.” And he took me up in a biplane. It was double seats in the back and he and I were in the back and the pilot was in front.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And I felt it was the best thing that ever happened in the whole world, a biplane. I said, “What the hell makes this thing stay up?”

Host: Yeah, really.

Jack Boyd:And he tried to explain pressure distributions over a wing and what have you, and I didn’t understand it. But he did persuade me to go to Virginia Tech. So in 1944, January I went to Virginia Tech.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:It was during the war, remember?

Host: Yeah.

Jack Boyd:So you had to go through fast. So I finished in three years with a bachelor’s degree in aero M.E.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And he finished before I did, of course. Anyway, a guy came around interviewing from Langley Field and there were other places that I’m sure that he went. And I said, “Well, I’d like to interview, but I want to get out of Virginia.” He said, “Well, you know we’ve got a center way out on the West Coast called Ames Aeronautical Laboratory situated at Moffett Field, a Navy base.”

And I said, “Well, if you can interview me for that I’d like to go.” He said, “Well, I can’t do that. I’m just a Langley guy,” but he interviewed me anyway. And about a month later I got a note saying, “I got you a contact at Ames, so you can at least talk to them.” So I did and they made me an offer within a week.

Host: Really? Just over the phone?

Jack Boyd:Yep, over the phone. And the guy – I never could remember his name – but he was the one that helped me get out here. This was like in December. I graduated in December of ’46, and they said, “You’ve got to be here by mid-January.” So January 15, 1947.

Host: You just loaded everything in a car and just —

Jack Boyd:Oh, no, no car. I didn’t have a car.

Host: Okay. That’s fancy talk.

Jack Boyd:My whole family didn’t have a car. I came by train.

Host: Really?

Jack Boyd:And I met two nurses on the train. That was interesting. All the way across the country we talked. They got off in LA [Los Angeles] and I came on up here.

Host: Oh, wow. So when you first got to Ames, 1947, the war was about winding down at that point. What were you working on straight out of the gate?

Jack Boyd:No. The war had apparently convinced the country that we needed to do more work in aeronautical engineering.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And to back up a bit, remember Lindbergh was on the NACA, the Advisory Committee, amongst many other people; Orville Wright and many other well-known folks, Jimmy Doolittle. And he was afraid of what was happening in Germany, and he said to the President, “You ought to put together another center to do aeronautical research. And it ought to be as far away from the East Coast as possible.”

Host: Far away from Europe.

Jack Boyd:The President said, “Go find a place.” So Lindbergh, apparently, went around the country and he picked this site for Ames. So Charles Lindbergh was our grandfather, I guess.

Host: I remember hearing about it at the time, where it made a lot of sense because a very temperate, very moderate climate, typically 70 degrees, no humidity.

Jack Boyd:And there were a couple of airplane builders out here on the West Coast, mostly in the LA area. So that was another draw in this direction.

Host: Yeah. I remember going to Kitty Hawk [North Carolina] and checking it out. And they were talking about the wind, the hills and the sand, and it was like the perfect area to do test flights.

Jack Boyd:I think Lindbergh had the three reasons for picking this site. I think those reasons were it’s cheap electric power and you’re going to build big wind tunnels. That was [a big one]. The weather is good, so you can fly research airplanes –

Host: Year-around.

Jack Boyd:Right, practically year-round. And it’s in the middle of a really fantastic group of universities; the University of California, Stanford, Santa Clara, California State. So he said that’s three reasons to put it there.

Host: Wow. You hop on a train. You move all the way out here. What were you working on? How did that start off?

Jack Boyd:Well, a guy named Walter Vincenti, who was the Branch Chief — and, incidentally, he’s celebrating his 100th birthday.

Host: Wow.

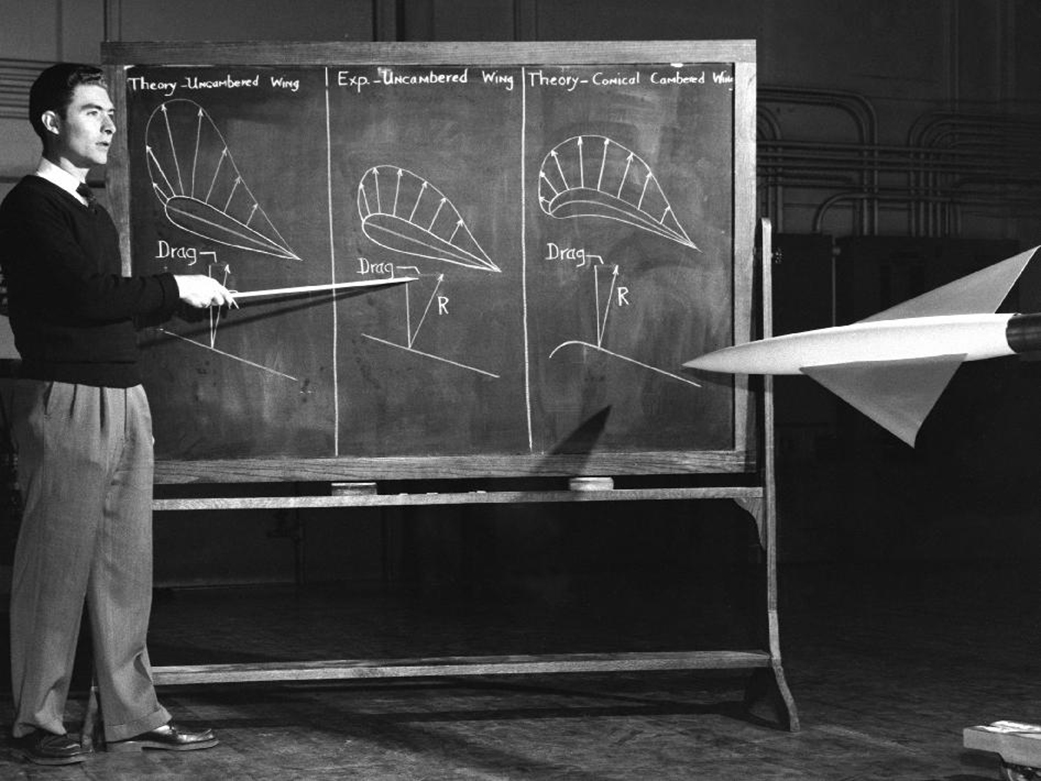

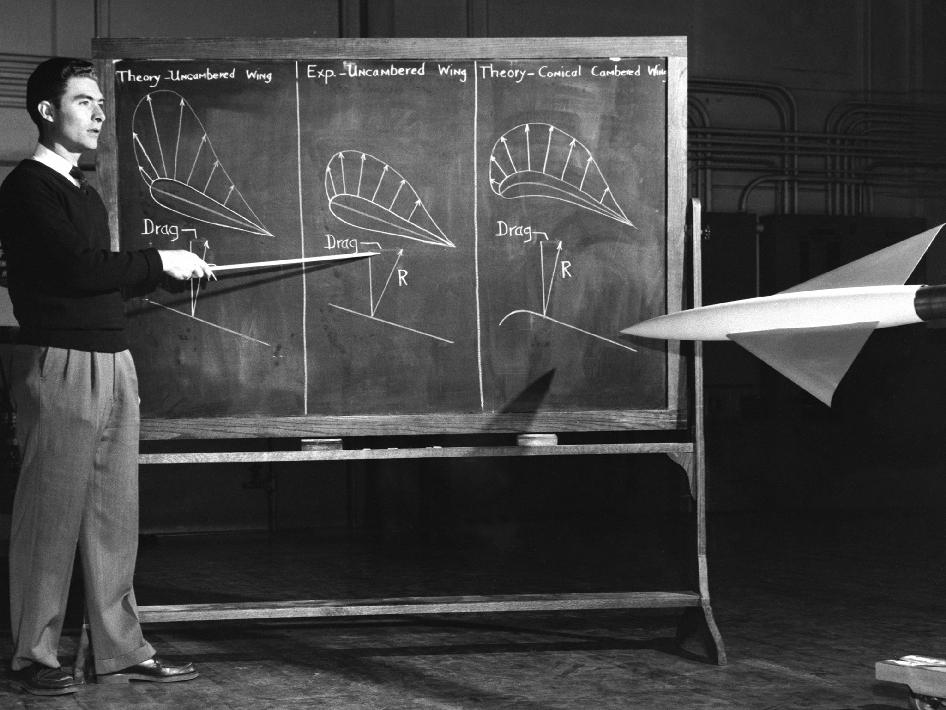

Jack Boyd:He was a Stanford professor. He left there and went here. R.T. Jones, who developed the swept-back wing, was my sort of mentor, too. He said, “Read everything you can, and then we’ll give you a little project to do.” And he said, “In the project, what you do is get yourself a swept-back wing built in the model shop and test it in the wind tunnel that we’ve got.” We’ve got a wind tunnel that went 1.53 Mach number.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:And so I started out. You did the whole thing. You drew up what you wanted, you took it to the shops, you monitored it through the shops, you brought it back, you put it in the wind tunnel, and you tested it at supersonic speeds to see what the drag, lift, pitching moments were like.

Host: How were you able to measure that?

Jack Boyd:We had little balances we put up inside the fuselage of the model. The models were only about this big.

Host: Like six, nine inches.

Jack Boyd:I’ve got one in my office. It’s about this long and about this wide.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And it had a little spherical shape body. I had what we call balances. They were electronic and you put them up inside the fuselage and tested the forces. And it read out the forces on a manometer board sometimes. And we’d put little holes sometimes in the wings to get the pressure distribution over the wing.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:So that was complicated. We had to have a little bit bigger model for that.

Host: Yeah. And at that time, you mentioned Langley and I think of their research center, Ames Research Center, now is a part of NASA, but back then Langley was a part of NACA.

Jack Boyd:Langley, of course, was the first center, we were the second, and Glenn [in Cleveland] was the third.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And Dryden was the fourth. There were four NACA research centers and that was it. In 1958 when we converted over to NASA there were those four centers.

Host: So how was it during that time, having lived through it all, working in the wind tunnels, being here at a research center studying wind tunnels and how airplanes work, and then moving it into the beginning of the space race and forming NASA? How was it?

Jack Boyd:Well, it was exciting, but we didn’t really know that we were doing such exciting things. We came to work every day. We were sort of the dull, plodding engineers. And as you know from recent publications, we had these computers – lady computers, not computer-computers – who sat in a room and reduced the data for us. And at my wind tunnel we had about six or eight ladies sitting doing the data reduction.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:And when they said the engineers were married to their computers, they were quite right.

Host: Quite literally.

Jack Boyd:Sometimes they married their computers. It was a funny process. You got the model built. You put it in the wind tunnel. You got the data out of it. The computers reduced it to lift, drag, pitching moment, and then you wrote a report and the industry came and picked up the data almost as fast as you could run it.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:They were really desperate for that data from the wind tunnel to determine what shapes, what configurations they should build.

Host: That’s right. It’s kind of easy now for people to think of the aeronautics industry, or even the airline industry. But back in the early days, aeronautics was heavily government-funded through the airmail.

Jack Boyd:Sort of like the airmail, right.

Host: Yeah.

Jack Boyd:When the government started funding the airmail, then the private companies took it over.

Host: Exactly.

Jack Boyd:When the government started funding research in wind tunnels, many of the companies started building their own wind tunnels. But they really liked the NACA wind tunnels because we had all sizes and shapes. We had wind tunnels that were two feet across and tested at Mach numbers of one, two and three. Then we had the big, huge 40-by-80 [foot test section], which you could put a full-scale airplane in and just test it at landing and takeoff speeds.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:So NACA had a whole spectrum of wind tunnels.

Host: So for these companies it’s like, at a certain point, why make your own wind tunnel when they can just come over here and use the ones that the government already built.

Jack Boyd:Yeah. That’s right. They made some specialized ones of their own. But when they really wanted to get a wide spectrum of data over a wide range of Mach numbers, they would come to Langley or Ames or Glenn.

Host: And it’s not too different even now. We still have these private companies that will come and use the wind tunnels and do data.

Jack Boyd:Yeah. We still do that for other companies. And we put out what we called annual reports, NACA did. And in those annual reports was about 10 or 12 papers, which summarized the most relevant data of that year. The companies had that, too, to work with.

Host: Wow. It harkens back to thinking of NASA and the beginnings of NASA. The first A, aeronautics, it’s an important part. And people tend to think of NASA as space and rockets.

Jack Boyd:NASA, it still is National Aeronautics and Space Administration. When I started everything was aeronautics, 100 percent. I would say now, probably less than 25 percent of that effort goes into aeronautics. And the budget, I think, typifies that; an $18-plus billion dollar budget.

Host: Yeah.

Jack Boyd:I think, what, about a billion-and-a-half goes into aeronautics, something like that.

Host: Well, it’s almost like those priorities, or even just the model kind of changed over time, where aeronautics, originally being heavily government-funded, and then the private sector would use different – really because the industry didn’t exist – but over time public/private partnerships, until a fully-fledged aeronautics industry –

Jack Boyd:I think in way it compares to the railroads and the airmail.

Host: Oh, okay.

Jack Boyd:Railroads and airmail were first government funded, and then the private folks took it over.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:I think aeronautics was privately funded and the big companies took it over. Same thing is now happening in space, when we have the multiple companies working on launching rockets into space, both in orbit and soon to the moon, I think.

Host: Yeah.

Jack Boyd:So I think it’s similar to many things that have happened in the last 200 years in our past. We go from government-funded to private-funded. And that’s exactly what’s happening in space.

Host: Excellent. So talk a little bit about when NACA started morphing into NASA. How was that as an employee sitting here working during that time? You’re just going to your job, grabbing your coffee.

Jack Boyd:Actually, we didn’t notice it too much at Ames. I think Langley noticed a bit more because they started –

Host: They’re closer to [Washington] D.C., too.

Jack Boyd:Doing space work before we did.

Host: Oh, okay.

Jack Boyd:They had the task force. I don’t know what, task group they called it. A colleague of mine that went to Virginia Tech was a guy named Chris Kraft. Chris Kraft was probably well known in the space world. He started at Langley, and then he went with the Space Task Group to set up Houston, JSC [Johnson Space Center]. And he actually became the director at JSC. He retired some years ago because he was a couple of years older than I am. He’s an old dude.

Host: Even just kind of thinking of that morphing NACA into NASA, let alone this area, even at that point it’s not these tech companies like what it is now. It was like orchards and fields.

Jack Boyd:It wasn’t Silicon Valley when we started. Hewlett Packard started in a garage around the late ’40s and became a biggie.

Host: Yes.

Jack Boyd:And the other companies started to grow up around it. I think the rationale that Lindbergh used to put Ames here was not dissimilar to what the companies – they came out and found good weather. They found fantastic universities, and they just started building up their companies around it. They had the talent here. That was what they were looking for. All in kind of one place, too. Between LA and San Francisco there must be eight major universities; Southern Cal, Stanford, et cetera.

Host: Yeah. And it’s going to make sense, the conclusion that the government made of let’s put an aeronautics research facility here amongst these universities, great weather. And then, eventually, those companies started following suit and finding the same thing.

Jack Boyd:Well, the whole West Coast had Boeing, Lockheed. The big companies started here. Texas had a few starting, too; Transcontinental Transport started in Texas.

Host: So NACA becomes NASA. For the most part, I guess the day-to-day lives here didn’t really change that much. Your funding came from different places, I guess.

Jack Boyd:It was a very slow change for us. If we hadn’t started thinking about space in the early ’50s – remember, we didn’t become NASA until ’58. People like Harvey Allen, who developed the blunt body [vehicle shape] concept, he began thinking about things burn up when they come into the atmosphere, particularly if they’re sharp. And he did the calculations, and he thought about it intuitively, but then he developed the computations that could go along with it.

And he said if the body was blunt it will take the heat away from the leading edge and it won’t burn up so fast. He had a good friend called Fred Whipple, who had what he called a Prairie Network. And he had pictures of all across the country. He’d take pictures of these fireballs that came shooting into the atmosphere. And they would recover them and discover, to their amazement, that they were all kind of blunt shapes.

The pointed ones had burned off to the blunt shape and they survived. So he and Harvey became good friends. And I think that was part of the intuition that Harvey used to develop the blunt body.

Host: And that’s the funny thing. I think for people who aren’t super familiar with aeronautical engineering, I think for the layperson you tend to think to go faster, to survive entry you have a pointy object. It’s like cutting through the water, it’s pointy. Cutting through air –

Jack Boyd:And that’s true up to a point. Up to a certain velocity that’s true. Because R.T. Jones, in developing the swept-back wing and the sharp leading edges, said you want low drag. To get low drag you need a sharp one. When you’re coming in fast you want high drag, just exactly the opposite. You want a high drag vehicle so it will slow down in the atmosphere and not burn up.

Host: So you make it blunt and fat.

Jack Boyd:Right up front you make it blunt.

Host: So then that way it takes on that impact and it’s kind of dispersed.

Jack Boyd:Yeah. It doesn’t have to burn a sharp edge off. Otherwise, you wouldn’t survive.

Host: It probably seems obvious now, but back in the time that was a huge discovery.

Jack Boyd:That was phenomenal. That was intuition. Harvey Allen, who worked here, and who started at Langley, incidentally, graduated from Stanford and he always wanted to come back home. And when this laboratory was formed, he was here like that.

Host: Oh, nice.

Jack Boyd:It was December of ’39 it was established. And by the early ’40s people were coming out. Harvey was number five, I think, five or six. The first 20 or 30 people at Ames came from Langley.

Host: Okay. Because it was already there, so that makes sense.

Jack Boyd:They were there. They were aero engineers. They had been educated all over the country. But for a number of them this was home, so they wanted to get back here. And Harvey developed the concept on this theorem that said — that’s the reason Ames gets into trouble, we innovated it — he said, “Proceed until apprehended.”

Host: Nice.

Jack Boyd:That was his motto.

Host: It kind of fits for the general personality of the area.

Jack Boyd:It still does. And that’s why we get in trouble still.

Host: As a part of NASA, obviously, Ames has always been aeronautics focused about studying airplanes and studying how things fly. But when did you start seeing some of the more space science, or some of the other things start trickling in?

Jack Boyd:DeFrance was a brighter guy than people gave him credit for. He was the first Director. He was Director from 1940 to 1965, for 25 years. I think in the mid-50s, when Harvey was doing the blunt body stuff, Smitty got the feeling that we needed to broaden ourselves. And if we’re going to broaden, what would we do it in?

Well, the universities around here were doing all sorts of studies, and life sciences and space sciences began to be an area that looked like we should get into. He felt we should broaden our base, because aero was going to be a smaller part. He was very, very bright in that sense. Ornery old guy. He was the one who started it, and he started getting a few people here and there he would hire. A guy named Chuck Sonnet was a space science person. A guy named Chuck Kline, who was very well-known in this area and was a life sciences guy.

And he hired the two of them and they started looking in two or three people groups of what we might do. In fact, both of them were sort of responsible for some of experiments we had on spacecrafts. One interesting story was with Carl Sagan. Carl was a Professor up at Berkeley, and some of us went there and took courses from him. And he really got us excited about planets. That was his field.

So people liked that. In fact, Harvey Allen and S.J. DeFrance and what have you, who brought these few people in in different fields to broaden our base, it’s what saved us.

Host: I’m sure that’s a precursor to how —

Jack Boyd:Without him we would have been closed by now.

Host: Oh, yeah. As a precursor to how it is now, the Ames portfolio is vast. It seems that you think of certain NASA centers that focus on aeronautics or rockets or human training —

Jack Boyd:The only thing we never got into was propulsion. We sort of stayed clear of propulsion because we recognized Glenn was the main propulsion one and they knew more than we did. With Langley we always competed because they were aeronautics and we were aeronautics. So they were our natural competitors, but they were also our mother center.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Jack Boyd:They spun us off.

Host: Yes. So during this whole time, Jack, were you still always doing engineering?

Jack Boyd:Myself?

Host: Yeah. Were you still sitting in the wind tunnels?

Jack Boyd:For the first 15 years, ’47 to early ’60s. I got to know Harvey Allen pretty well, and he was my Division Chief. And he goes, “Do you want to become an Assistant Director?” We had aeronautics and one for space. And he said, “You ought to come up and get a little training for a year or two and see if you like the administration building.” And I said, “I don’t want to do that, really.”

Anyway, he persuaded me. And I got interested in management in the early ’60s and came to the admin building and was sort of a Tech Assistant to the various Org Directors, both in space and aeronautics. And that’s when DeFrance decided we needed some additional training and called me up and said, “Have you ever heard of the Stanford Sloan Program?” I said, “No.” He goes, “Well, I think you ought to go. It’s a business degree.”

Host: Oh, cool.

Jack Boyd:“And we need somebody who is an engineer, who understands –” —

Host: The technical side.

Jack Boyd:“the business practices,” or whatever.

Host: Nice.

Jack Boyd:And I said, “No, I don’t want to go.” He said, “I didn’t call you to ask you if you wanted to. I called you to tell you you were going.”

Host: Yes, you were volun-told.

Jack Boyd:So I was the first one to go to the Stanford Sloan Program from here. After that went about 15 people.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jack Boyd:And that was in ’65.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:And it turned out to be a very good experience because I met all sorts of people, in addition to the Stanford Profs.

Host: Oh, I’m sure.

Jack Boyd:It turned out the people who were my classmates — there were only 14 of us, and six PhD students — became presidents of Boeing and of Lockheed. So the contacts were remarkable.

Host: I’m sure. That’s almost like one of those big advantages. A lot of government agencies have some variations of go get a grad degree at a school, or even the military does the war college thing. But I think one of the best byproducts of that is you just meet people, you have contacts, whether it’s interagency government, or if it’s within big companies. You just have all these contacts and it just builds that more and more.

Jack Boyd:My contacts were the most important thing at Stanford, I think.

Host: Yeah. And so after that, when you come back —

Jack Boyd:Accounting I didn’t like very much.

Host: Nice.

Jack Boyd:After I came back? Let’s see. After I came back it was ’66. I became the Assistant Director for Aeronautics. And the guy asked me to come over to space and became the same thing. We had two pieces, aeronautics and space by the late ’60s. Remember, that’s before NASA was formed still. No, it was ’58. It was just a little after that.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:We were formed in, what, ’68? Wasn’t NASA?

Host: Yeah, something like — somebody online is screaming as they’re searching Google and yelling the answer for us.

Jack Boyd:And from there on, I was asked to go to Dryden to be the Deputy Director. I didn’t particularly want to go down to the desert.

Host: Yeah, just outside of LA. Now it’s Armstrong.

Jack Boyd:Yeah, now it’s Armstrong. But the administrator called my wife and said, “We want Jack to go down to the desert.” Keep in mind, we had four kids by then. And she said, “Sure, he can go. I can do without him for a year.” So that ended my objection to going Dryden. It was fun. It was a good experience, though. And I came back here as the Associate Director for Ames. We had one Deputy and one Associate. So you really got sunk into management stuff at that point.

Host: So did you ever feel that itch, though, of wanting to go back into the wind tunnels, and wanting to go back to the research stuff?

Jack Boyd:After the Stanford Sloan Program I didn’t want to go back to the —

Host: Yeah.

Jack Boyd:I don’t think I could have.

Host: It kind of moves fast.

Jack Boyd:When you lose several years, you kind of lose track of what the relevant stuff is.

Host: Yeah. Like staying on top of the latest research.

Jack Boyd:The process of going from a wind tunnel jockey, to management at Ames, to management at Headquarters, to management at other centers, to management at the University of Texas system, it was sort of a natural progress, as you look at it.

Host: Yeah.

Jack Boyd:I’ve been here now 70 years. It was 70 years ago I started. But as I’ve talked about, some of the time was spent away from Ames.

Host: Okay. You spent some time away at different universities and different things. At what point in time did you come back to Ames? And then was it just right back into administration?

Jack Boyd:I came back to Ames in ’92. And I was going to retire, but whoever the Director was said, “Why don’t you come out and just sort of be part-time?” Well, that didn’t work. So I became an IPA. They call them IPAs.

Host: Okay.

Jack Boyd:With different companies around the IPA person and to locate them at wherever they think he’s most valuable to them. So I did that with the University of California, Santa Cruz, and with Penn State. First with Penn State, actually. So I was IPA with Penn State and the University of California, Santa Cruz, and now I’m — what am I? A NASA Redeployed Annuitant.

Host: Nice. Obviously, you’ve seen not only Ames morph and change over the years, but even just this general area of going from orchards and fields, to now these tech companies. But for somebody who doesn’t know anything about Ames, you’re out talking to people or you’re visiting somebody in Texas or whatever, and people are asking you —

Jack Boyd:Talking about Ames is the most exciting thing. And they love to hear about it because almost everybody around us is interested in space exploration. They really are. And if they find that you worked here, that really turns them on and they want to know everything about it that you know about.

Host: If you’re talking to somebody who doesn’t know anything about Ames, what are the main things that you tell them?

Jack Boyd:Well, I ask them if they’ve ever heard of supersonic speeds. And most of them haven’t. What is supersonic speed? Then I explain Mach waves, Mach cones, sound barriers, etcetera. And how valuable it would be to get from point A to point B in one hour, instead of five. Flying from New York to London in a Concord is like two-and-a-half hours. Now it takes you what, seven or eight?

So to get around the world as the world is opening up, as I think people understand, it’s very valuable to do this kind of basic research. Otherwise we have to depend on some other country to do this, and that doesn’t serve anyone at all. So they love the idea of space. They don’t know why quite. You talk about Mars and they think of little brown men.

Like Carl Sagan designed that plaque that we have, that was put on the Pioneer spacecraft. Ames made a little spacecraft called Pioneer back in the ’70s that went beyond Pluto. And Carl was working with us and he designed a plaque. He said, “ET is out there. I firmly believe there is extraterrestrial life somewhere in the universe, and someday we’ll find it. And if this Pioneer is going to go beyond the solar system –” — and it went beyond Pluto — “we ought to put something that would tell people what we’re all about.”

So he designed this very interesting plaque, which has two human forms on it, for one thing, a male and a female. And it shows this solar system with the Sun and nine planets, and this spacecraft comes from planet number three. So you’ll know, one, where we come from, and you’ll know what we look like. And some smart person said, “Well, they’ll think they look just like us, except we don’t wear clothes.” If you see this plaque, it’s two nude humans.

Host: So considering your experience of the time that you’ve seen NACA go to NASA, and all the different range of changes, what’s the main advice that you give people who are coming in, the next generation, the new people getting hired in?

Jack Boyd:Do three things. One, listen to the older folks who are here because they really know what they’re doing. They’ve developed a remarkable ability to build a new airplane or build a new spacecraft. Be sure you get along well with people because you have to depend on the people. There’s no question about it. You’ve got to depend on people. So if you’re a manager, in particular, you better be able to get along with them and get along well.

And two, don’t be afraid to go out and learn something new, as I have tended to. I wanted to be an engineer. That doesn’t mean you can’t learn about other things. So do those three things and you’ll probably get along pretty well.

Host: Excellent. And then thinking about NASA as an agency, as somebody who clearly cares about what NASA does, is there something that really excites you about something that NASA is going to be doing? Or is there just general advice if you were to give advice to the new administrator or to anybody, or to the entity as a whole?

Jack Boyd:I would say, one, you’ve got to get along well with Congress, because you need their support, and with the administration. The more important thing, I think, is to encourage young people to go and take things in school and to learn about things. One, that they are interested in and, two, that they can make a contribution for.

I think space exploration is not unlike the early days of when we opened up this country, or when Columbus discovered America. Explore, explore, explore and go out and do different things, and don’t be afraid to do them. Because if we had been like some people who think we ought to back away from all this activity, we would probably still be sitting in Spain with Queen Isabella’s relatives ruling us.

Host: Yes.

Jack Boyd:So don’t be afraid to do new things.

Host: Or even be still sitting in caves somewhere in Africa.

Jack Boyd:You’ve honestly got to learn to live with the political system. You may not like the Congress, you may not like what they do, but you’ve got to learn to be able to explain why you’re doing is important. And important to not just the country, but the whole human race.

Host: Yeah. Sometimes it’s easy to sit back and complain about things that frustrate you. It’s quite another thing to try to understand motivations and understand things and try to make it work.

Jack Boyd:And another thing you’ve got to do is understand what you’re doing well enough to be able to explain it to a novice.

Host: Totally.

Jack Boyd:You don’t want to just explain it to an 18-year-old who is really excited, but you’ve got to explain to a 50-year-old who is going to support you with his tax money.

Host: Yes.

Jack Boyd:You’ve got to be able to explain that. And don’t be impatient with them. Because it took you a long time to get where you are and to understand what you’re doing, so it’s going to take them a while to understand it. They’d rather put their money into building a new road or building a new transport system on site. And those things are important, but you can’t turn off the exploration goals that people have, I think.

Host: Absolutely. And then for folks who are listening who have questions for Jack, talking about inspiring the next generation, or anybody who has got any questions about your experience here, we are on Twitter @NASAAmes. We use the hashtag #NASASiliconValley. So if people have questions, we’ll take those in and we’ll bring them over to Jack, and we’ll see if we can get any kind of —

Jack Boyd:I would be happy to talk to them, or try.

Host: Exactly. Well, we’ll point you in the right direction. We’ll get you all set up. But thanks for coming on over. This has been fun.

Jack Boyd:Okay. That’s it?

Host: Yeah, this is it.

Jack Boyd:Okay.

[End]