We’ll begin with your childhood, where you’re from, your early years, early schooling, or other experiences, especially if there was anything about them that might have oriented your thinking or ambitions, toward the career that you are pursuing.

I was born in a small town in Bosnia. It was a part of former Yugoslavia at that point. My mom has an incredible knowledge of plants, especially the medicinal ones, most of which came from being a pharmacist. So early on she imparted this love of plants. My upbringing was very much rooted in the land that surrounded us, even though I lived at the top of a five-story walk-up apartment building. My tiny hometown is at the intersection of two large rivers. There were these embankments along the two rivers, and we spent a lot of time there, walking, exploring. I grew up surrounded by nature. I spent many weekends on the nearby farm, a homestead really, of my grandparents. I loved and still love animals. We managed to support a steady menagerie of convalescent animals in our small apartment. Biology came naturally, as an extension of this intense interest in the living world around me. Biology was the first science course we took in school. Then came chemistry, followed by biochemistry, a sort of mix of both worlds.

My first experience with observing the microscopic world involved a demonstration of onion membrane cells using a microscope by our fifth-grade teacher. We did not have access to the experimental side of science. The education system there could not support lab work. It was all theory. But theory made sense, so, paradoxically maybe, I think where I grew up had a lot to do with my interest in science.

My first experiences with doing experiments came much later, in college, so I might as well tell you about the rest of my education. After finishing elementary school and most of the high school in Serbia, we moved to the U.S. just before my senior year of high school. My undergraduate degree was in biochemistry at the University of Tampa. I still remember the first biochemistry lab, extracting an orange protein from a heart muscle. I was hooked. My Ph.D. was in biochemistry at Florida State University. I should mention that I spent a few years in New York. Towards the middle of my studies, my lab moved from Florida State University to Hunter College of the City University of New York (CUNY). I did my experiments in Manhattan, then went back to Tallahassee to defend my dissertation— working on catalytic RNAs called self-splicing introns. They have an interesting evolutionary history, which led me to become interested in evolution in general. At that time, an NPP opportunity became available with Mark Ditzler. And that is what led me to NASA Ames.

Well, you’ve covered a lot of ground and if you don’t mind I’m gonna go back and slow it down a little bit and ask if there’s anything about your family, like do you have siblings or anything like that, that you want to share?

I have a brother, who lives in Florida. His interests are not related to science.

And when you came over to the U.S. you mentioned the fact that you were in Florida dictated the schools that you initially went to, but what was it that made it Florida? Was it something that your mom and or dad chose because of employment or some such?

It was one of the available options and we all liked the idea. We took a family vote and made the decision democratically.

I understand. Then going to New York, Manhattan, was that following a particular discipline or a mentor or somebody in your program?

Yes! My mentor, Nancy Greenbaum. She moved the lab to New York. Solving high-resolution 3D structures of RNA takes considerable time and I was well into it. It really wasn’t a difficult decision to make. She sweetened the deal by getting a brand-new NMR instrument, installed on the 13th floor of our building. I mention this because it was a small feat of engineering. The high floor of an old building had its challenges, the building swaying was just one. NMR instruments are giant magnets, and their environment must be just so. Usually, they are on a ground floor or in a basement, but because a subway (a large ferromagnetic object) runs just below Hunter College, it was not an option.

While our instrument was being set up, we made use of the NMR facility at the CUNY Advanced Science Research Center, in Harlem. It was surreal putting my precious, fragile samples in these long, thin glass tubes in a backpack, protected in every way I could think of, to take on a subway uptown to Harlem. Sometimes I would walk east, over to the Rockefeller University with my samples, where Dinshaw Patel, my mentor’s former mentor let us use his NMR instruments. Does that count as fieldwork?

Well, you became very cosmopolitan in your living situations, living all over the world at a very young age, you’re still at a very young age.

Living in many different parts of the world has been a big part of my life and it’s shaped how I see the world. New York City itself is a microcosm of the world. Studying there exposed me to so many different ideas and cultures. And now, California, Silicon Valley, in particular, is another example of a multi-cultural environment that makes you think of the world as a more unified place.

And you said that your connection into Ames was through the NPP with Mark Ditzler?

Yes, a colleague of mine had met Mark at a conference in New York and he told me about this opportunity. The postdoc involved using in vitro evolution to study the emergence and early evolution of life.

Talk to us about your work here at Ames, what you’re currently working on, what you started with Mark Ditzler on, and also any interesting developments, findings, and so on.

I’ve worked on a few projects in the seven years that I’ve been at Ames, all involving questions of the early evolution of life. Around the time I arrived at Ames, Loren Williams’ group at GA Tech was looking into the effects of iron on the activity of biological RNAs. RNAs use metal ions for structure and function. Today, the dominant ion is magnesium. In some ways, reduced iron is similar to magnesium. Before the rise of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere, the concentration of soluble (reduced) iron in the ocean was much higher than today, so the question was whether biological RNAs can use iron in place of magnesium. We wanted to investigate the impact of some of the environmental parameters on the evolution of functional RNA molecules in general, one of the questions being whether RNAs naïve to biology can use iron — is iron something that works for RNA in general? Using in vitro evolution can answer these questions. As it turns out, pH matters. At neutral pH, a lot of the RNAs in my evolved populations were the same and they could easily switch between magnesium and iron, with no loss of function. This is really interesting because it shows that once upon a time, while oxygen levels were minimal, these molecules could have evolved in the presence of iron and then could easily switch to use magnesium after all this iron oxidized and precipitated into solid deposits. This means that, at least when it comes to the use of metal cofactors, the rise of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere wouldn’t have meant the end of the living world as it was.

Another project we’ve been working on for a few years was just accepted for publication in the Nucleic Acids Research. One of the questions we asked is a fundamental one — the question of chance and necessity — if the tape of life is replayed, would the outcomes be similar to what already happened, or would they be completely different? We now have experimental data that support the idea that evolution is pretty deterministic on the molecular level. Another implication of my work is that RNAs tend to increase in complexity by adding new structural elements to a conserved core. This is interesting because we see this in biology, in the case of the ribosome, for example. The core of the ribosome is conserved, and the complexity increases by tacking on these new structural elements, sort of like adding layers of an onion, starting very small and growing bigger. The reason this is important is that these data tell us that we can unravel how these giant molecular machines evolved. We can actually peer back in time and look at these ancient structures nested within the modern ones.

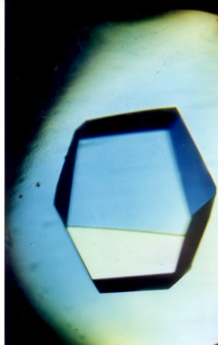

Crystal structure of the ribosome obtained in 2000. The ribosome is the most complex molecular machine found in the cell.

That is interesting. I’m not a scientist so I’m stuck a little bit at the place where you are talking about iron and oxidation and magnesium which I think of as being inanimate so how do they relate to this evolutionary biochemistry aspect of it?

Life today uses minerals and metal ions for function. They are not alive, but a part of living things. Some of the examples of the more complex iron structures that are at the core of modern metabolic processes are thought to be remnants of earlier life. Life coopted these structures.

It is generally agreed upon that transition from inanimate matter to life takes a large number of steps. First, there were rocks and organic molecules. Organic molecules became more complex, forming longer polymers. Some polymers that didn’t end up becoming tar gained function, and maybe were encapsulated, and voila! Darwinian evolution began. There is life! Of course, this is an oversimplification. The details of this are where it gets tricky. Just to name a few, the types of chemistries available are defined by the environment. We have not constrained the plausible environmental parameters. The space of unknowns is staggering.

Evidence for stromatolites, some of the earliest fossilized microbes in what we think are 3.5 billion-year-old rocks in the Dresser Formation in Pilbara, Australia.

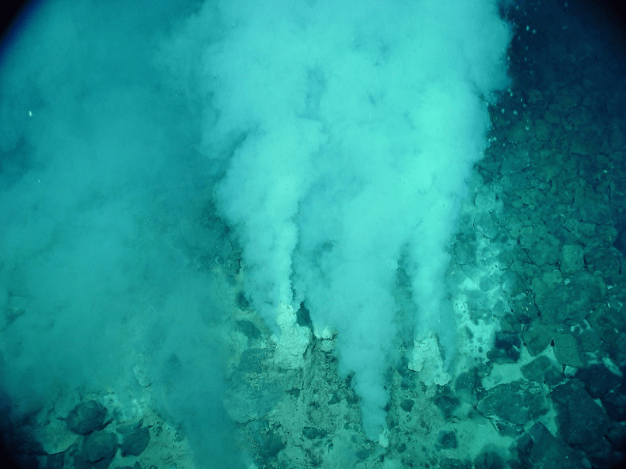

Another type of location that is of interest to the origin of life research.

Interesting, for sure, and important. How would you respond to a question about the place of this or its importance in the strategic priorities of NASA and defending it to the taxpayer who actually pays for all the research that we do? Why is it important to the citizens of the country, or the world?

I find it that people are so fascinated by the origin of life that it really doesn’t take a lot of defending, to be honest. How life started, where we come from, are we alone in the universe are questions that have and still do fascinate people. Origin of life is a large portion of what astrobiology is concerned with, so for example, how building blocks assemble, what drives those assemblies towards the first protocells, the development of Darwinian evolution are all lines of investigation that astrobiology investigates.

It’s been interesting to us as we’ve conducted these interviews how many, I’m tempted to say all, but almost all, when we probe into the significance of the work they do we find a thread leading back to that question, the origin of life, and specifically is there life elsewhere? Are we alone and unique in the universe? Are these processes, these chemical processes, as far as we know would they be the same everywhere and can we ever find out if we are not the only life form?

Exactly! Understanding the chemical and evolutionary space and possibilities is essential to guide the search for life in the universe.

Sure it will tell us, for one thing, what are we looking for and what might it look like? There are lots of ideas about that.

Oh and I noticed another thing: I was looking at the next question guiding our conversation and it asks what a typical day is like for you and I noticed when I did some background on you before this interview that you were actually in the new science building, not actually now because of the COVID-19 situation but you are one of the lucky few that were selected and assigned to be in the new building. Were you actually in it before the COVID shut down?

Yeah, it’s a new building designed with collaboration in mind and I am excited about the prospect of working there. We had just moved in and were getting set up as the pandemic reached California.

So you have that to look forward to.

Oh yeah definitely, such a great set of team-oriented coworkers. I am really looking forward to new collaborations.

It was designed as a collaborative laboratory and that will be a wonderful thing so congratulations on getting selected because I know that you proposed competitively to be in there.

Yes! Our team is very proud to have been selected to work there. Bringing us together in this new space catalyzed the formation of the Center for the Emergence of Life. Sara, you built the web page.

Yes, I remember. Fun little project. What is your typical day like and what do you like best and least about your job.

Depending on the stage of the work we’re doing it varies. If we’re in the starting stage, I mostly spend my time in the lab. Then we sequence our samples and once we have our sequencing data, we do bioinformatics analyses. And while that stage is done, I spend a lot of time in front of a computer. I make predictions about the structure of these RNAs based on the bioinformatic data and test them by doing biochemical assays. I like everything about what I do really.

As far as my daily routine now, I have a three-year-old at home and my husband and I share the responsibility of taking care of her during these times. Mornings are my time to work, so I mostly spend my time doing data analysis, writing, and reading. We just finished writing up the manuscript I mentioned. I did a lot of grant writing over the summer and right now, planning for writing more proposals.

Do you do mostly like lab research or do you ever go somewhere else, into the field, or is it mostly in the lab?

So before it was mostly lab work. The bioinformatic side of it is computer work and that can be done away from the lab. One of my projects is funded through the ISFM direct funding model, with Mark and Andrew Pohorille as well as other collaborators. We have been planning to do more computational work in the near future, partly, as a safeguard against the longer-than-expected closures.

You’re a young researcher, but is there a favorite memory from your research so far perhaps research findings or breakthrough or something that you found exciting or unexpected, something like that?

Our findings are generally very incremental. It’s like we paint a picture, and every new finding adds a new facet. So, I wouldn’t call this a huge breakthrough, but this latest research that has just been published is exciting. It’s work that tells us about the basic nature of the living world — learning how the evolution of biomolecules takes place. Finding that RNA molecules get more complex by conserving their core structures and then adding new segments to make them more active, and all the implications that stem from that — I am very proud of that work.

We’ve talked about your career and what you were doing now but here’s an off-the-wall sideways question: if you weren’t a researcher for NASA have you ever thought of what your dream job would be?

(Laughs). There was no way to tell that I would end up here. I think that a chain of very unlikely events led me here. At the same time, I could never see myself not doing science or something related.

Maybe another kind of science?

It would probably be applied science or something based on science. It would really depend on where I was living at the time. Where I come from in the Balkans, where you have a very small economy, the practicalities may shape your interests more strongly than here. It’s typical for those who are interested in science to go on to medical school, pharmacy school, maybe chemical engineering. The options are pretty limited locally. Of course, a lot of young folks leave too, for Europe maybe, so who knows. There are more options abroad.

Now, living in Northern California probably impacts how and what I think about. Sustainability is on my mind constantly, what it means for different parts of our planet. I can’t help but wonder if this isn’t something I would be involved in a different life.

Most people that we’ve interviewed are very happy with where they wound up and they say this is my dream job. But as we press them on that we’ve gotten answers that range from ballerina to a funeral director. So you just never know. You said your route to getting to where you are has been kind of a circuitous one, not a straight line.

It was a stepwise progression.

That’s typical, but what advice would you give to someone, a young person just starting out who would like to have the kind of career that you are pursuing.

Let me get out my soapbox for a minute. The environments in which I grew up introduced me to rigorous math and science education early on. Another important aspect and you probably wouldn’t think this of the Balkans, but girls and boys were treated equally. All my math teachers, from elementary school through high school were women. And I should note, these were women with degrees in math. Then I thought this was normal, but now I think that this is empowering. So, a lot of it is systemic and a matter of one’s environment.

As an individual, I would say that it is important to try to understand yourself and your interests, regardless of outside pressures. To do this, one should try different things and not once, but maybe a few times, maybe at different times. We all have the capacity to do many things but learning what makes one happy may take time. Here is an opinion we hear a lot — you have to show up and you have to ask questions and most of the time you have to be insistent. Maybe this alone isn’t something that will change your circumstances instantaneously, but this attitude definitely helps.

And therefore, it is so important that we can offer internships and research experience to undergraduates at NASA Ames. I feel privileged to be able to mentor students in the Young Scientist Program that is offered every year through the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science (BMSIS). Unfortunately, research opportunities for local students are lacking. Before the pandemic put everything on hold, I worked with community colleges in the area to bring their students to Ames. The hope is that through building these relationships, we can foster growth within a diverse talent pool. It’s a win-win.

Yes, we’ve heard that. You can’t, actually, there are no guarantees. If you go forward in your life and in your work and you do the best you can, circumstances will often direct your path but if you are persistent you will wind up in a good place and most of our people didn’t actually intend to wind up at Ames or to stay here, but they found their way here and then they love it so that’s been their life. But it could’ve just as easily been somewhere else. And they still would be pursuing what they are interested in. And that’s I think what makes the difference that you have something that you are passionate about and we can feel the passion as you talk about it, and that makes life so bearable.

You mentioned that you have a daughter. Anything else you would like to mention about your family? Do you have pets, do you have trips you like to go on, things you like to do, that kind of thing?

I have a husband and we have a dog. It has been interesting these last seven months. It’s been a joy watching my daughter grow up before my eyes, in spite of the stresses of juggling all of the aspects of our lives.

And I usually throw in a question now that we’re in this Covid thing has that been a hardship for you in terms of your commute or are you saving a lot of time not having to commute or do you live close enough that it doesn’t make any difference?

I fully embraced the lack of commute. It has been one less stressor in life. We scaled back to owning one car. And imagine what the lower commute levels are doing for the environment. Earlier in the pandemic, there was a sweet spot of discovering our local hikes in the South Bay. Maybe I’m a little fatigued with hiking by the water-treatment plant at this point, but maybe I’ll get a second wind. But, on a serious note, this pandemic has really brought to focus the unsustainability of our pre-pandemic travel rates, the question of where one lives and works, and how we have fun. My life in 2020 reminds me a lot of the life my parents had, simpler times. As much as it pains me to think of the lost work opportunities, my hope is that we all take a deeper look at what aspects of this “new normal” we want to keep before returning to “life as usual”. Who knows, maybe this year I get to participate in a virtual grants panel, something I didn’t feel I could do with a young one at home because, normally, it involves extended travel. I’m just guessing here, but maybe more women get to participate in general if that becomes the norm.

And you working in the lab would probably put you at the front end of those who will eventually be allowed back on site where you have some part of your work that you can’t do at home. And that day is hopefully soon but probably not as soon as we would like. The county moved to a less restrictive condition just recently and Ames is looking at ways that it can potentially do the same thing.

One of our favorite questions is we know you love your work but what do you do for fun?

(Laughs) Umm, I miss cultural activities, art, live music. San Francisco has a lot to offer, but everything I do these days involves my daughter and my dog. And it’s all been scaled back to only local activities. Generally, I like outdoor activities. I learned skiing early on as a kid in Bosnia and that’s an activity that I’ve done in all the places that I’ve lived. You can ski in Tennessee, and it’s not such a huge drive from Tallahassee if you’re motivated. I did a lot of scuba diving in Florida. A few of my electives at the University of Tampa were scuba diving. I enjoyed outdoor rock climbing in New York, hiking, and camping. Toward the end of our stay on the east coast, in Connecticut, before we came to California, my husband and I took up 420 sailings. 420s are these tiny, fast boats, so you’re just above the surface of the water. They capsize easily. I remember, our teenage instructor was going with us through the drills of righting one out of the water, and I made a decision that I would do anything necessary to avoid having to do this again. So just trying to stay dry was quite fun! We sailed slightly bigger boats in the Bay Area. We hope to go to the mountains this winter because my daughter really enjoys the snow. We mostly do things like snowshoeing and we pull her in a sled.

Any other hobbies or talents? Are you musically inclined?

It took three years of piano lessons to realize that my heart and talents lay elsewhere. I enjoy listening to music, many different kinds. It really depends on my mood.

You’re like me! I don’t play anything I wish I did but I love listening to it, so that’s a good answer as far as I’m concerned.

My husband plays the piano, well, he plays a lot of instruments, he’s musically inclined and I think my daughter may be too, so I’m lucky.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that’s not related to your science work?

Raising my daughter. It’s really fun to see myself in some of what she does. She gets really intense with flowers, bugs, rocks… I’m also proud of my COVID-garden that I tend to with my daughter.

How about who or what inspires you?

My colleagues are impressive people, and generally speaking, people that I work with at Ames are professionally, highly inspirational.

Do you have a favorite image of space or science or something that you do that we might perhaps find on the wall of your office that tells something about your interest or your motivations? Sometimes we can come to know people better when we understand things like that.

And is there perhaps a favorite quote or something that you find appealing or motivational? You can think about that, too. Is there anything that you wanted us to ask about that we didn’t ask? Or that you want to add?

Here is one attributed to Mark Twain: “I have never let my schooling interfere with my education”; and one credited to Charles Darwin: “In the long history of humankind (and animal kind, too) those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.

It was really nice to chat with you both. Thanks for having me!

We try to make these practically painless! (Laughs)

Do you ever go back to Bosnia, do you still have family there?

Most of my family is in Bosnia now. I go back every few years. It is such a long trip, especially from California. We went to Croatia last year, the Adriatic coast, in an attempt to recreate some of the childhood memories I have of the area and it was lovely. I was so grateful for having gone last year in light of the current events.

Thank you so much, Milena.

Interview performed by Fred and Sara on 11/3/2020