Episode description:

NASA has a record of Earth observations going back more than 50 years. What might be in store for the next 50 years? In this finale of our Earth series, we hear from two scientists helping to chart the course of NASA Earth science. There are still many unanswered questions about our home planet. As the only planet that we know to have life, studying Earth is also crucial as NASA searches for other habitable worlds.

[Music: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

PADI BOYD: You’re listening to NASA’s Curious Universe. I’m your host Padi Boyd.

JACOB PINTER: And I’m your host Jacob Pinter. This is the fifth and final episode of our Earth series. If you missed the other stories, no worries. You can listen in any order. Just know that there are even more wild and wonderful adventures waiting for you all about how NASA explores our home planet. We’ve unpacked missions that study the ocean, which is so big that you need to see the full picture from space. We’ve heard about NASA’s agriculture program, which puts information into the hands of people who need it. And, because air pollution is the world’s number one cause of premature mortality, we’ve heard how NASA measures air quality and studies the atmosphere we live in.Just scroll back in your podcast feed. You’ll find those stories and many, many more.

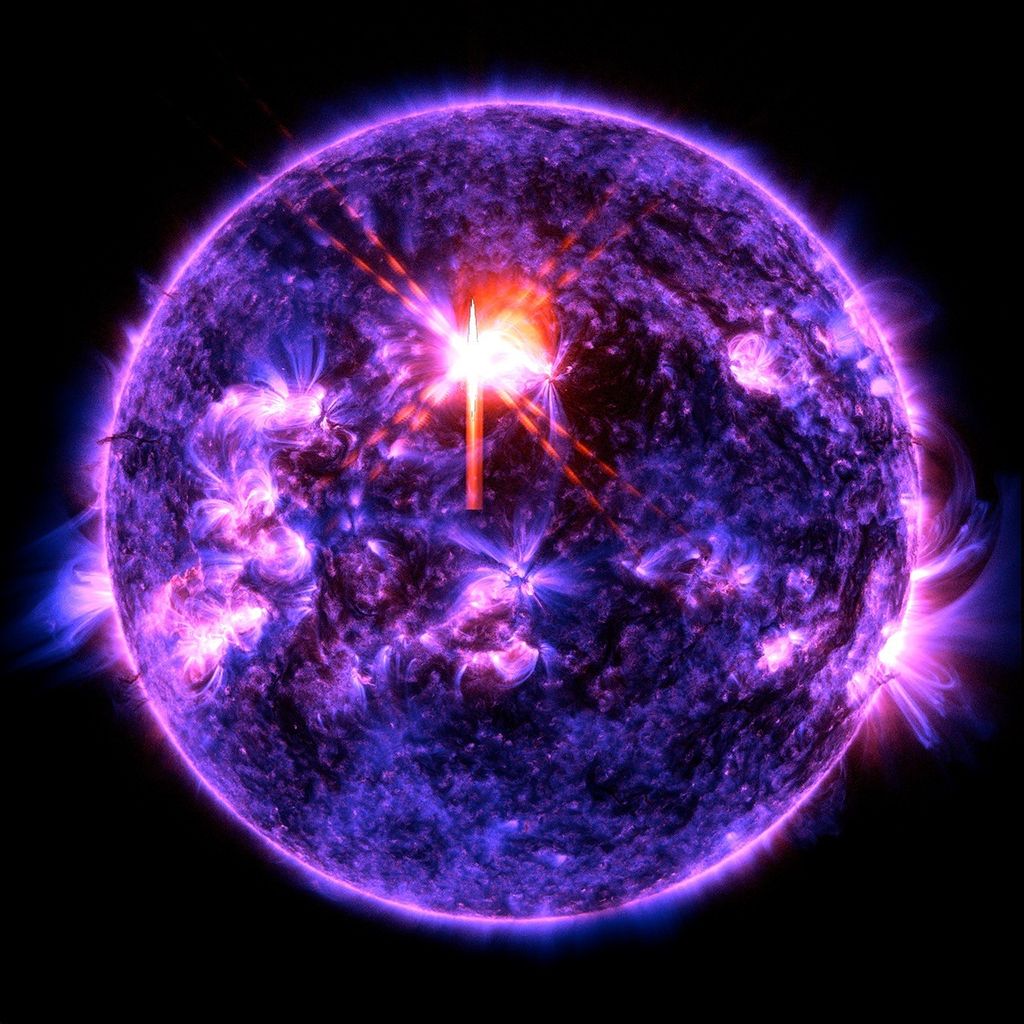

PADI: NASA Earth Science has a long history. A major milestone happened back in the 1960s, when the first astronauts to orbit the Moon saw our home planet from a distance. It was breathtaking, and it led to an iconic photo called Earthrise.

BILL ANDERS: Oh my God, look at that picture over there! There’s the Earth comin’ up. Wow, is that pretty!

JACOB: From space, astronauts saw the Earth as one interconnected system. Just a few years after the Apollomissions …

Clip from archival video: ERTS-1, the first experimental ERTS satellite … (fades out)

JACOB: … NASA launched a satellite that gave us new views of Earth.

Clip from archival video: It offers an ideal means to monitor change: an ocean chewing away at the edge of a continent. A desert’s advance. A volcano’s fury. … (fades out)

JACOB: Today we have a record of Earth observations going back more than 50 years. We can see how Earth’s surface has changed during that time, and scientists can also use what we know about Earth today to create models that help us understand our planet’s distant past and what might be coming in the future.

PADI: I wanted to hear more about the future of NASA Earth science, so I brought together a couple of people who are making it happen.

[Music: Glide Shot by Paul Hartnoll]

CHRISTA PETERS-LIDARD: I’m Christa Peters-Lidard. I am the Director of Sciences and Exploration here at NASA Goddard, and I have been at Goddard Space Flight Center since 2001.

DALIA KIRSCHBAUM: And I am Dalia Kirschbaum. I am the Director of Earth Sciences at NASA Goddard. I have been at Goddard since 2009, officially.

JACOB: Just to put a fine point on this: NASA has Earth scientists across the country working together. Christa and Dalia lead a slice of this at the Goddard Space Flight Center.

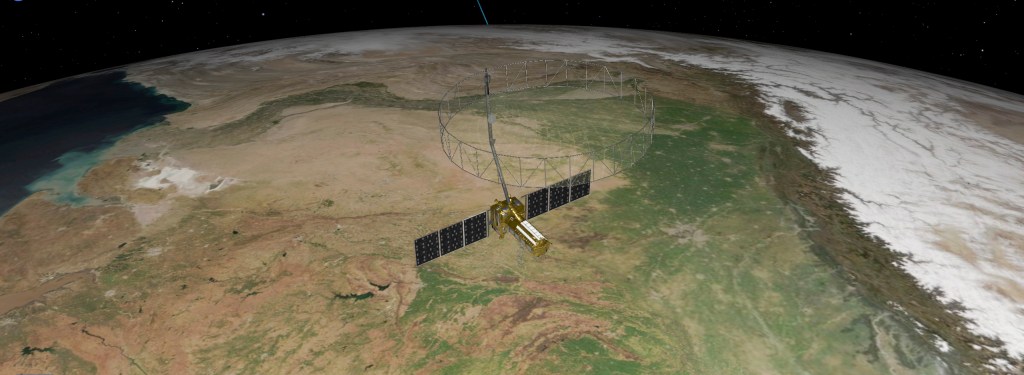

PADI: As technology gets better, so does the way we understand Earth. We keep building on the data, creating a clearer picture. For a couple of decades, a trio of satellites called the Earth Observing System gathered crucial data.But those spacecraft are nearing the ends of their missions, so this is a time of transition.

JACOB: Padi, can I butt in for a second?

PADI: Sure.

JACOB: So you’re an astrophysicist, besides being the host with the most of this podcast. You’ve talked on this show about your work on NASA missions that discovered planets beyond our solar system, thousands of them. Today we know that there are many, many, many of those planets out there. The next step is to try to find planets that are habitable, right? And maybe we could even find life out there somewhere.

PADI: Right. But look, this is a really tricky problem, and we have to be careful. Because as far as planets that have life on them, it’s a really small sample size. We only know of one. So we have to start from what we know, which is Earth. We basically have to squeeze all of the information we can out of Earth so we can recognize the signs of a habitable planet when we see one. Earth is our only example of a planet that is both habitable and inhabited.

[Music: Launch Codes by Jez Hurst, Andy Hopkins, and Jacob Nicholas Stonewall Jackson]

Anyway, there’s so much more I could say. But as Earth scientists, our guests today Christa and Dalia have a unique perspective and a different perspective, and I really wanted to hear how they think about this.

JACOB: Now, NASA is not the first group to study Earth and not the only ones who do it. Humans have been trying to understand the world around us for about as long as there have been humans.

PADI: As astronauts have pointed out over and over, from space Earth has no borders, and you can see all of these different processes working together. Studying Earth with this holistic view is its own discipline. It’s called Earth system science.

CHRISTA: Thinking about the Earth as a system and how all of its cycles are interconnected. So it’s really about using all the data and using all that knowledge—and our models, which encapsulate the knowledge—to analyze the past and give us clues about the future.

DALIA: We develop new technologies that have never been flown before to understand things like how our atmosphere is changing, how the surface is evolving, and then we use them to create these really well calibrated data sets that our researchers use around the world, but also Fortune 100 companies use that data to better understand their own business models and to advance their capabilities. We really seek to understand those interconnected systems to advance scientific knowledge, and there are so many impacts that benefit each and every person around the world every day.

PADI: I had a ton of questions for these two, and it’s always exciting to be in the same room with a couple of other NASA scientists at the top of their game. Christa and Dalia have similar research interests. In fact, before their current roles they each ran a group called the Hydrological Sciences Laboratory. So we started with the basics. I asked Christa to explain what hydrological sciences are.

CHRISTA: So hydrological sciences are the study of the water cycle, and in the current formulation of this lab it’sfocused on Earth water cycles, which—just to be clear, since there are other water cycles out there.

DALIA: And I think some of the unique things about the Hydrological Sciences Lab is the ability to take a lot of different satellite data and bring it together through what we call data assimilation to understand how our water is changing over the Earth. And my work has really focused on how we can take that data and apply it to things like natural hazards. Somy research area is really in applications of hydrologic hazards like landslides. And so we kind of have both ends of the spectrum of looking at the water cycle, kind of the inputs and kind of the impacts at the end.

[Music: Dream World by Colin Nicholas Baldry and Tom Kane]

PADI: What is NASA’s place in, like, the whole earth science enterprise?

DALIA: You know, I was really inspired by this quote from Mae Jemison, an astronaut. And she said, “When you look at the Earth from space, you realize that our planet is a beautiful interconnected system, and we are all in this together.” And I think that that is the power of NASA Earth science, is that with this vantage point from space, we can see the whole Earth, how it’s connected—everything from the depths of the ocean to the tops of the atmosphere—and with that vantage point from space, which of course, is NASA’s mission, we can understand that, not only at the surface and airborne capabilities, but from satellites as well.

CHRISTA: Yeah, and you know, I would add that Earth science is about the first habitable planet we know about. And so everything we know about life and how life works on a planet is based on Earth, and so we are using the Earth as an analogue as we develop signatures of potential life elsewhere.

PADI: A very exciting area for sure. You know, that’s very engaging to me, someone, an astrophysicist who’s very motivated by exoplanets and finding an Earth 2.0 out there if such a thing were to exist. But as an astrophysicist, also, everything that I study is very far away. We don’t touch it. What does it feel like to study the place that’s right under your feet?

CHRISTA: Well, you know, Earth is full of surprises. I mean, there’s so much we still don’t fully understand. I mean, there was a paper a few years ago where one of our scientists, one of our senior scientists, counted the number of trees in the Sahel region of Africa. And first of all, there were way more trees than we thought. So he used imageryand an artificial intelligence model trained to recognize trees. You have to do that to count them at this scale. And sobeing able to count individual trees, first of all, and then being able to count the carbon stored in those trees, right, which, you know, again, that’s just—it sort of blows your mind. Like, wow, we don’t really understand. I mean, another mission that Dalia and I have worked on, the Global Precipitation Measurement mission, is like a CAT scan for hurricanes. Again, there’s things that surprise us all the time about Earth, even though it’s our home planet, there’s so many things we don’t fully understand. And I love surprises, so I think that’s one of the great things about being a scientist and having data that tells us things we didn’t know before.

PADI: Dalia, what do you think?

DALIA: With the Earth at night, we can see communities changing. We can see where natural disasters are causing power outages, and that is really important data for other organizations to provide support. We can see that from satellites and provide that understanding that interacts with our Earth system understanding to get a much richer view of what it’s like to live in our communities and in our world.

[Music: Detailed Analysis by Carl David Harms]

PADI: Is there a place on Earth that your work has made you see differently now than you did before you started?

CHRISTA: Yeah. I would say for me personally, it’s been some of the work that I did with the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, you know, looking at—using satellite data to predict the potential for drought and food shortages, being able to see that in real time, you know, looking at the soil moisture and the drought and looking at the vegetation from space—so being able to see the real life impacts of the Earth system observations that we’re studying.

PADI: Right.

DALIA: And to just add on to that, you know, we don’t do this in a vacuum, unless we’re in space, which—obviously I had to make that joke.

[laughter]

DALIA: But we do this in partnership, right, with our federal partners. We do this with commercial partners, right, being able to—you know, we provide these long term observations like Landsat, right, it’s the longest running observation of our surface with these very well calibrated measurements, and the commercial industry uses those to calibrate and evaluate their products, to go higher resolution. So this complementary relationship and understanding things like agriculture is just a critical piece of the puzzle, is that we’re really all in this together. There is this important connection we have across industries, across partners, both domestically and internationally.

PADI: So it’s not that there’s just one place that you see differently, it’s that you see everywhere differently, the whole planet differently. That’s very, very cool. So I want to talk about the future of NASA Earth science. But first, how has NASA Earth Science evolved during your time here?

DALIA: You know, when I started, I was able to go into the clean room when the GPM satellite was fully assembled. This was about the size of a small school bus, and I got the full bunny suit on, and I it was the first time I’d ever done that. There were engineers working behind me, and I just looked back and just thought, how amazing this satellite, in a few short months, the impact it was going to have on the world, right? And it has. The continuation of understanding precipitation measurement is just critical, and that long term record is foundational to understanding changes. So being able to be kind of in the presence of that was just a very humbling time for me. And that’s when I started, right?And so now we’re looking to the future and we are looking to a dearth of measurements for the future.

[Music: Searching Questions by Carl David Harms]

DALIA: Where we started—and kind of the outlook that I had starting—was this proliferation of data and these huge,impactful satellites. That’s not the case going forward. And so I see this as both a challenge and an opportunity, because I think that we may not have these big flagship missions in Earth science in the same way that we had when we started—at different times but similarly.

CHRISTA: Yeah.

DALIA: But we have an opportunity to think about doing missions differently, doing missions in a way that enables faster science, that enables more creative use of AI and modeling and technology development, working with the private sector, working with industry, all different types. And so as much as I’m, you know, concerned about the future of what our fleet looks like for NASA, I’m also energized by this opportunity to say, How can we do things differently, more efficiently, faster return on science, to be able to understand our interconnected Earth and make measurements that are critical to furthering our understanding of how we live and what we need to survive?

PADI: I love that you brought up being in the clean room and seeing this observatory with your own eyes, and then they are our eyes in the sky.

DALIA: Yes, indeed.

PADI: So what’s the biggest mystery or unanswered question about Earth that you want to solve. You said we’realways learning new things and getting surprised. Is there anything that you’re curious about now?

CHRISTA: Yeah, well, I think there’s some—there’s a big question about how the water cycle is changing right now. I mean, there was just a paper that came out on, I think, in Nature, on how global soils have been drying. And so again, like, yet another surprise. Like, Oh, wow. OK, so what does that mean for agriculture? What does that mean for ecosystems? The unsolved question is, how will the Earth system change and especially the water cycle? Because people will feel changes most acutely through the water cycle, right? We depend on water for sustenance, for food, for everything, and so I think that is still an unknown question. And how can we manage water more efficiently, you know, in the future?

PADI: Dalia?

DALIA: One of the things we’ve been thinking a lot about in addition to that, is better understanding the air we breathe, right? So we’re talking about the planetary boundary layer. It’s from the surface to about, eh, a kilometer up, maybe. So literally, 8 billion people live in this area, and we can’t measure it very well from space. And so we are developing new technologies that are getting at better resolving this place where air quality affects our lungs, where the exchange between the surface and the atmosphere, right, is critical for weather forecasting. I’m excited to learn how we can do that through kind of a disaggregated fleet approach to really—kind of an all-hands-on-deck effort to measure the air we breathe in a different way.

PADI: So you mentioned earlier, Christa, that Earth is an amazing example and our only example of a habitable planet, the only one that we know of. But you know, exoplanet scientists are basically driving astrophysics now with that desire to understand the thousands of planets that we know are around nearby stars and sift through them to see how similar they are to Earth, the place where we know life can form, has formed. How do you take what we know about Earth—which, you know, sounds like so many systems that are interconnected, water, land, the atmosphere, we’ve talked about humans, vegetation—how do you use what we know about the Earth to kind of untangle all of that variability to help guide the exoplanet scientists to understand what it is that they could be looking for that would be like those telltale signs, versus what could be maybe a false flag?

CHRISTA: Yeah, this is a great question, right? Because when we’re looking at an exoplanet, you know, the first thing we will see is its atmosphere. And so from Earth, we can look at Earth as an analog and say, Well, what components of the atmosphere might indicate life? And so these biosignatures, right, that come out—I mean, I’m not an expert in this, but I think, you know, we like to imagine that you can use Earth’s spectrum to identify those things which are uniquely produced by life, and then look for those elsewhere. You know, understanding the type of life we have on Earth and the large variations in life, I think that’s another, right. So there’s like, what might life look like, and how can we use the huge variability of what’s here on Earth to help imagine what might exist elsewhere?

PADI: And you also talked about the modeling of the atmosphere and how you can go back in time—

CHRISTA: Oh yes.

PADI: —and study, you know, the Earth through these eons of drastic change.

CHRISTA: That’s true! Because, yeah, so—I mean, so if you know, the same models that we use to model the Earth can be used to simulate potential exoplanet atmospheres. You know, you go back, way back in time on Earth, you know, the atmosphere looked different. And so you can actually take models and simulate what a planet billions of years ago might have looked like—or, you know, many hundreds of millions years ago—you know, because the atmosphere has changed over time from the dinosaur era, right, back in geological time. And so that then can be used to simulate what you might see if you were looking at a planet earlier in its evolution like an Earth, but it might look like Earth did a long time ago, not like it does now.

PADI: So it’s like there’s this whole family of Earths, right? We’re not just studying Earth today, but there’s this whole spectrum of Earths.

CHRISTA: Like paleo Earth.

PADI: Very cool. Very fascinating questions, I think, when we are talking about all the decisions we can make today based on what we know about Earth today and extrapolating those backwards and maybe forward.

[Music: Into the Void by Gage Boozan]

PADI: You did mention earlier that moment where the Earthlings here got to see Earth as a system all together in the Apollo era, I think that’s—as an astrophysicist, when I think about that moment, I see that, as you know, the moment that changed everything, as far as our view of Earth and Earth Science and Earth as our home planet.

CHRISTA: Earthrise in particular, right, to me, touched off a lot of the, you know, environmental movements in the ‘70s, and so, you know, as a child growing up in the ‘70s, right, I distinctly remember, you know, a lot of anti-pollution and things happening in the 70s that—you know, just raising the consciousness of folks to be more careful about our own planet. Now it’s really standard that we—everyone expects to look at the Earth, you know, through satellite data. You can get it on an app on your phone. You know, it’s so commonplace now. There is this broad evolution that has happened because—I mean, it’s not just me, it’s like my family. I think they’re, everyone’s just generally attuned to things more than they used to be.

DALIA: Yeah. And I think, you know, you have these astronauts that are now going to the Moon and ultimately to Mars. The question is like, What do you hope they get when they look back and see Earth? And the first thing that struck me was, I hope that they see something worth coming back to. Right? Because I think that there’s a lot happening right now. There’s a lot that we’ve seen our environment evolve, and we are understanding more and more about this opportunity to observe the Earth from space. We have new ways to look at the science and how those impact everyday people every single day. And so we, you know, want to be able to keep doing that, to keep showing those pictures of the Earth that don’t have borders, right? That help us to understand how these aspects are—of things are connected. And I think that that’s what Earthrise did, right? Earthrise had everybody look back and realize that they didn’t see—you know, they saw the Earth in a very different place than they see it on the ground. And I think we just need to keep being reminded of that.

PADI: And I think we will be, right, since we’re going back to the Moon, and we’re planning to stay so that a lot of people will be seeing Earthrise as part of their landscape of their day to day, Moon-day to Moon-day life. It’s going to be amazing. So now here we are. NASA has a record of Earth Observations going back more than 50 years. What do you hope the next 50 years is going to look like for Earth science?

[Music: Dysonsphere by Helene Choyer]

DALIA: We’re really entering an era of interactions in the Earth system that we haven’t seen before, and we’relearning, we’ve learned a lot about the physics—how our surface, our oceans, our atmosphere, interact, what those connections look like—but we’re moving a little bit into uncharted territory. We have been moving there, and understanding the past may not be an adequate prologue for the future. And so I think that where we’re going here is that I want to learn how we can better connect across disciplines, and also, how can we connect better with our communities to empower people with the data, the capabilities that we provide, both at NASA and our federal partners and beyond, to really create resilient, thriving societies? And so I think it’s—to me the next 50 years is about connections and impact as we push the boundaries technologically at NASA.

PADI: Christa, how about you?

CHRISTA: You know, I think about my kids, right? And where will they be in, you know, 50 years? The other big game-changing that’s happening is artificial intelligence, and where is that going to lead us, you know, when we have, you know, artificial general intelligence, and how will that help us to do make these connections? When there’s so muchdata it and it’s hard to analyze it, sometimes it’s hard to make a decision because it’s overwhelming. So I’m optimistic that these advances will help us to solve some of these problems, because Dalia is right. We are in uncharted territory. And so, you know, we’re going to have to maybe ask questions differently, think differently, use data that maybe isadjacent to what—the way we think or the way we’ve been trained. And so, you know, crossing boundaries might be more important in the future more than ever.

PADI: Dalia?

DALIA: And I think that there’s a really important role for NASA to play there. We’ve developed these kind of long-termdata sets that are authoritative, that companies use to build off of to run their businesses, or they use it to inter-calibrate their satellites. And so I think that that role of government in pushing the boundaries of technology in areas where there is no business model—we can buy down the risk for that then to transfer that technology for others to do it better, faster, cheaper. You know, we have to have kind of that pioneering motivation to then help others move fast.

CHRISTA: NASA research and research in general is the rocket fuel that drives our innovation ecosystem. It’s so critical that this rocket fuel keeps going to propel us to the next thing. Sometimes the applications don’t present themselves until decades after the initial work, and we can’t predict what the next technology will be. And so the seeds of it are probably growing right now. And so it’s so important for the nation to have those seeds—the nation and the world.

PADI: One last question for you both: What are you still curious about?

[Music: Argosy by David Naroth, Arun Ganapathy, and Victor Mercader]

CHRISTA: Well, I am super curious about where and when we will find life in the universe. I mean, I think that is one of the great questions of our time. So I’m just so excited. I mean, could it be on an icy moon? Could it be on an exoplanet? I mean, I’m just very curious about where that—when and where that’s going to happen, and I think it’sgoing to happen in my lifetime.

PADI: Fingers crossed.

DALIA: And I am curious about how we can continue to do better. You know, there’s so many “unknown unknowns” and those surprises going back to the beginning of what are we going to uncover with data that we didn’t even imagine was possible. And really, to me, that’s going to [be] what the next generation is going to look like. You know, how are they going to be situated to push boundaries, to come up with brand new capabilities that change people’s lives every day? And so that is really what powers me every day, is how we can do better for the future.

PADI: Well, thank you both for being here and talking to us. We’re very excited about NASA’s Earth science future. I can tell you guys are going to get us to great places.

DALIA: Woohoo!

CHRISTA: Yes. Thank you.

DALIA: Thank you so much.

PADI: That was Christa Peters-Lidard and Dalia Kirschbaum, and that’s a wrap on our Earth Series.

[Music: Currents by Jon Cotton and Ben Niblett]

We’re so glad you listened. Even though this story is over, there’s a lot more to explore. You can find more information about NASA Earth science at science.nasa.gov/earth. And you can see our global view of Earth anytime at earth.gov.

[Music: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

JACOB: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our Earth series was written and produced by Christian Elliott and me, Jacob Pinter. Our executive producer is Katie Konans. Krystofer Kim is our show artist. Our theme song was composed by Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of SYSTEM Sounds.

Special thanks to NASA’s Earth Science team, including Mike Carlowicz, Jake Richmond, and Janice Harmon.

If you enjoyed this mini-series of NASA’s Curious Universe all about Earth, don’t be shy. Drop us a line. We love hearing what you think, so don’t be afraid to leave us a review.

And I’ll bet that you have one or two friends who want to see Earth in a whole new way. Why not send them this episode, so they can learn more about our home planet and have some new fun facts to share at parties besides those ones they always use? Don’t forget, you can also follow NASA’s Curious Universe in your favorite podcast app to get a notification each time we post a new episode.

OK, we’re taking a break now. Don’t worry. We’ll be back soon with more wild and wonderful adventures.

PADI: Until then …

PADI and JACOB: Stay curious!