NASA finds the common fruit fly—Drosophila melanogaster—quite an attractive “model,” but not in the way you might think. This tiny insect is a biomedical research model that can reveal the basis for health and disease in many animals, including humans, because we share the basic biochemical machinery of life. NASA scientists are studying fruit flies to understand the molecular, genetic, cellular and physiological responses of whole organisms to spaceflight.

On Earth and in space, these models are easier to study than humans. Thousands of fruit flies take up little room. Multiple generations hatch within days, allowing for the study of diseases that would take decades to develop in humans. Because scientists can study many genetically identical Drosophila at once, they can design tests that have a high degree of statistical power, enhancing experimental sensitivity.

Every decade, NASA engages the National Research Council in Washington for a consensus opinion on which scientific questions are highest-priority and what research is needed to answer them. New facilities for the study of Drosophila that will be installed aboard the International Space Station in 2014 are part of NASA’s response to the National Research Council’s 2011 call for “a deeper understanding of the mechanistic role of gravity in the regulation of biological systems,” and specifically for multi-generational studies of fruit flies in space.

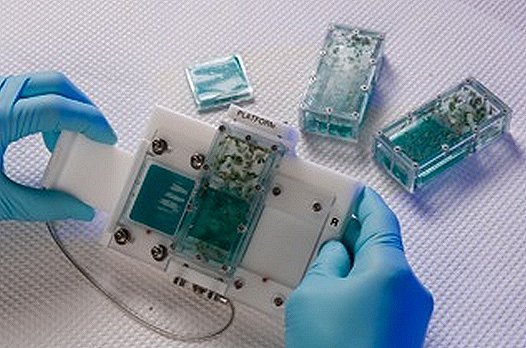

The Fruit Fly Lab is being developed by a team of scientists and engineers at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., based upon the prior generation system used aboard the space shuttle. Modified cassettes will serve as fly habitats for the new lab. Aboard the station, astronauts will use a food changeout platform to deliver in-flight “meal service” while preventing flies from escaping.

Although fruit fly studies have taken place in space previously, the Fruit Fly Lab brings advanced capabilities to scientists, enhancing their research. In addition to ensuring safe transport of flies aboard SpaceX’s Dragon cargo vehicles, the new system will support longer duration studies involving multiple generations of fruit flies, and—using NanoRacks centrifuges—will provide monitoring sensors and variable gravity conditions of 1g (Earth gravity), fractional g (such as moon and Mars gravity) and microgravity (weightlessness).

Three fruit fly missions are planned for 2014. Ames; Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif.; and the Sanford Burnham Medical Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif. are leading a cardiovascular study. A student-run study will investigate neurobehavioral changes that occur during spaceflight. The maiden voyage of the Fruit Fly Lab is set for 2014. These upcoming space station investigations benefit from previous experience gained from studies conducted aboard the space shuttle.

In a study funded by NASA’s Space Biology Program entitled Fungal Pathogenesis, Tumorigenesis, and Effects of Host Immunity in Space (FIT), fruit flies were housed aboard space shuttle Discovery during its STS-121 mission in 2006 for nearly 13 days to determine the impact of spaceflight on immune function. The results show that spaceflight alters the immune responses of Drosophila in ways that resemble the immune suppression observed in astronauts. These findings may help researchers develop countermeasures to keep astronauts healthy over long-duration space missions. Additionally, studies of compromised immunity are broadly relevant to human immune diseases on Earth.

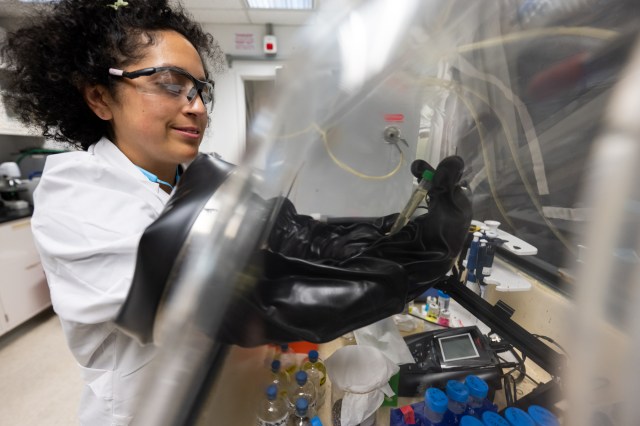

“Since the human immune system is complex, we used the Drosophila model to tease out the effects of spaceflight on the simpler innate immune system of the fruit fly, focusing on molecular pathways that perform similar functions in the human immune system,” said Sharmila Bhattacharya, Ph.D., principal investigator for the FIT study and scientist in the Space Biosciences Division at Ames.

One day before STS-121 launched, the researchers placed five male and ten female flies into each of ten fly cassettes. Half were loaded onto the shuttle, and half remained on the ground. On Day 13, Discovery returned to Earth with approximately 3,000 flies aboard. A new generation was raised in space.

Analysis began within hours of landing. The researchers compared the spaceflight group of flies with the ground control specimens. They looked at molecular markers of immune function and tested the ability of whole flies and fly immune cells to fight infection with the bacterium E. coli. Results showed that spaceflight affects the immune system in multiple ways that vary with the age of the organism. According to Bhattacharya, “It was striking to see how evident the effects of spaceflight were on the behavior, development and immune system of the animals that had returned.”

Previous studies demonstrate the usefulness of fruit flies for space biology research, paving the way for upcoming investigations. NASA’s Fruit Fly Lab will deliver advanced tools for long-duration spaceflight experiments, ensuring Drosophila melanogaster—a different breed of supermodel—continues to book appearances for extensive study in labs both on and off this world.