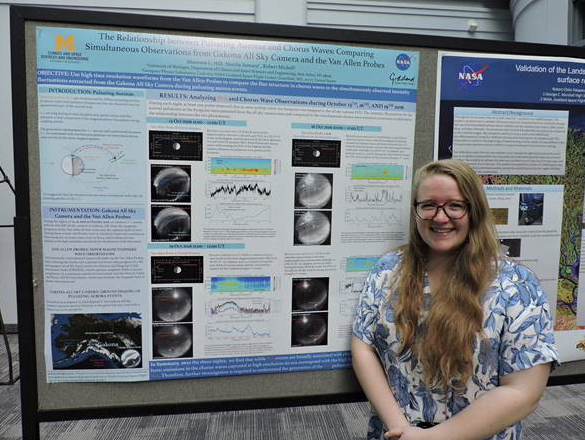

Conversations With Goddard: Intern Edition

Name: Shannon Hill

Position: NASA Intern

Office: Code 673, Geospace Physics Laboratory

Can you give us some background on yourself?

I am from northern Massachusetts but I went to school at Emory University down in Atlanta, and I am starting my PhD at University of Michigan in the fall.

What did you major in at Emory?

I did physics and astronomy and a double major in sustainable economics and global development. I also graduated with an Arabic minor.

What are you working on this summer?

I am in code 673, so I am in the heliophysics branch, and what I do in particular is magnetospheric physics, and what I am studying is a type of aurora called the pulsating aurora.

Can you elaborate?

When we normally think of the aurora, we think of the Northern Lights. And that is a particular type of aurora that has a very different global process in the magnetosphere. When we talk about the pulsating aurora, that’s a separate auroral process that is still kind of under debate as to where it comes from, why does it happen, and different aspects of it. You have the Northern Lights, and the magnetosphere responds to external stimulus from the solar wind. And as a result, it shoots energy down into the atmosphere, and that creates the Northern Lights. But with the pulsating aurora, you have another process that is separate from that happening in the inner magnetosphere. And right now, the thought is that course waves, which are just a type of instability within the magnetosphere, actually send electrons down separately into the atmosphere. The pulsating aurora gets its name because when you look up at the sky over quicker time scales, the aurora pulses and flickers and blinks its light.

How can you see that?

You use an all-sky camera. So, you set up this camera and it’s looking at the sky and you record videos. And then when you get those videos, you can play them back a bit faster.

When did you first get interested in this topic?

With the aurora, I didn’t really know anything about it until I got here this summer. But I was interested in magnetospheric physics from some past research I had been doing.

Was this at Emory?

Actually, I did an research experience for undergraduates at Auburn University over the summer of my senior year, which introduced me to magnetospheric physics. At Emory, I did astrophysics. And then coming here last summer I did more magnetospheric physics, but those experiences were kind of the inner magnetosphere and those kinds of dynamics. This summer was really interesting because I got to see whatever is happening in the inner magnetosphere has a consequence, and that consequence happens in the atmosphere we see. Now, I’m looking from the ground up at the atmospheric response to what was happening with these processes that have already been studied. So, it’s like I’m looking at it from a different perspective which is really interesting.

Have you found that rewarding?

Yeah. It’s given me a lot more of tan understanding of the global process of all of these things and the global dynamics of them. I also spend a lot of time just watching videos of the aurora, which is really cool and has really given me a better appreciation of the complexity of it. And it’s just really pretty and a lot of questions remain into how we can even model it or understand a lot of its structures.

What has been your biggest challenge this summer?

In the past, the research I’ve done for the magnetosphere has been satellite observations. I’ve learned with the Van Allen probe ho to manipulate that data and analyze that data and extract it from the instruments. But this summer for the first time, I was using all sky camera data. I was using ground based imaging, and having to learn how to use that data. And combining those data sets and learning those techniques has been challenging.

What is something that people might not know about you?

When I am not doing science, one of my favorite things to do is sing and act.

How do you think your NASA internship has helped prepare you for the future?

I am a first generation college student, and have never once really allowed myself to accept the fact that I could have these opportunities. So, being at NASA is unbelievable, and the biggest confidence booster that there could be. It’s helped me understand this whole world of science that I actually am a part of, even though it may not have seemed like I ever would be.

What is a piece of advice you would give other first generation college students?

Ask for help, because people want to help you. Always ask the questions you have because people want to teach you. And don’t stop dreaming and working hard, because it will end up working out in some weird way.

By Natalie DiDomenico

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center