When astronauts land again on the surface of another world, their limited resources will allow for a short window of time each day to explore their new surroundings. Instruments designed to quickly reveal the terrain’s chemistry and form will help them understand the environments around them and how they change over time.

To protect precious hours available for extraterrestrial scientific investigations, a team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland — the Goddard Instrument Field Team (GIFT) — is testing and refining the chemical-analyzing and land-surveying tools that will assist future human explorers of places like the Moon and Mars.

“It takes a long time to develop technologies that are going to fly to other planetary bodies,” said Kelsey Evans Young, a geologist at Goddard who helps develop space-exploration tools. “What we’re doing right now has a direct implication for what instruments are going to be selected for future space flight.”

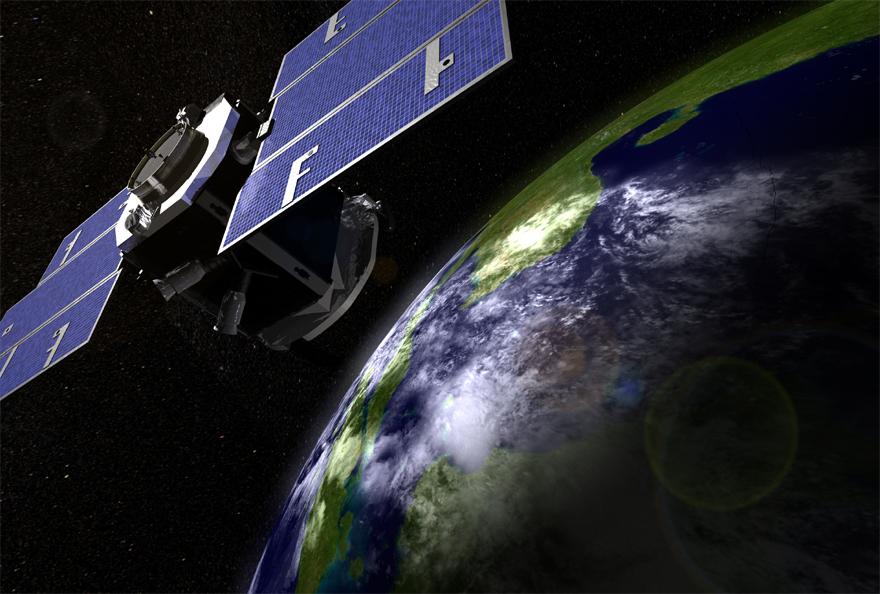

Many of the technologies Young and her team develop build upon ones that have already equipped robotic orbiters and rovers that sniff out the cosmos. NASA’s Curiosity rover, for instance, which is currently traversing Gale Crater on Mars, is studying the composition of soil with the help of spectrometers, or tools that identify what rocks are made of by measuring how their chemical elements interact with electromagnetic radiation. On Earth, too, instruments that reveal the chemical makeup of objects are widely used in fields including art restoration, archaeology and geology.

Credits: NASA

Though the technologies powering these tools already exist, NASA’s objective is to make the instruments small and efficient enough to help robots, and one day astronauts, analyze on the spot the composition of the surface of planets, moons and asteroids. This will allow for quick adjustments to exploration plans, said Young, and well-informed decisions about which few precious samples explorers can afford to return to Earth on a spacecraft of limited size.

To test instruments, Young and other NASA scientists and engineers have the enviable responsibility of deploying to exotic locations on Earth that share characteristics with moons and planets. These analog sites include out-of-this world landscapes such as the Potrillo volcanic field in south-central New Mexico. There, the desert geology that was shaped over millions of years by Earth’s volcanic and tectonic forces closely resembles our Moon’s. This is why Potrillo has served as a geology training ground for astronauts dating back to the Apollo era.

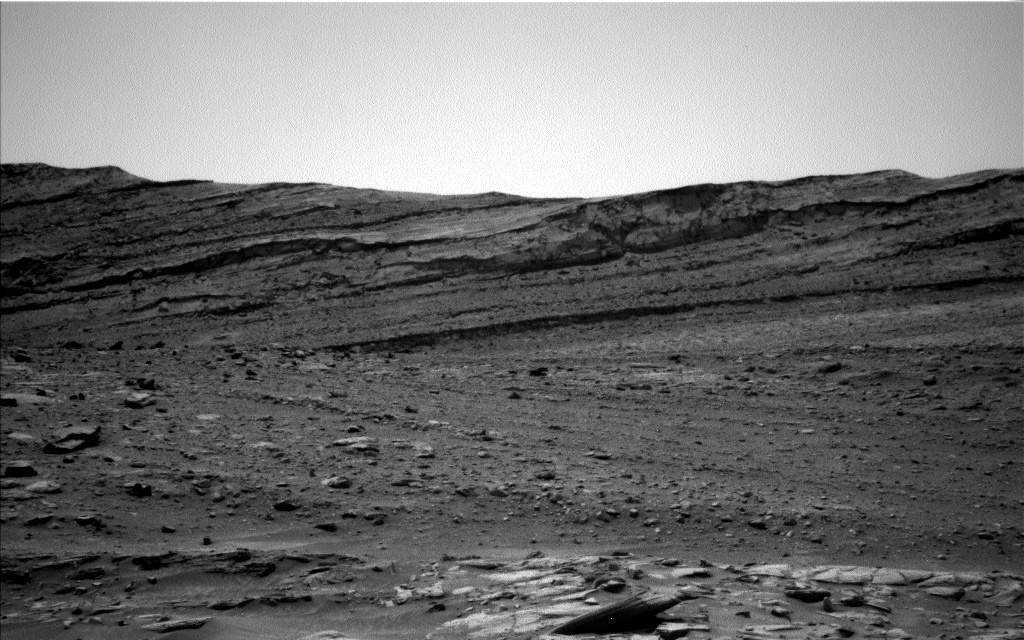

Another popular analog destination is the area around the active Kīlauea volcano in Hawaii, where lava cools to form basaltic rocks similar to those on Mars. Early in its history, the Red Planet had giant, active volcanoes, bigger than any on Earth. Studying the impact of fresh lava on Kīlauea, and comparing that to what we know about the geologic conditions of the far-away past, helps scientists understand how Martian volcanoes may have shaped that planet, and even the geology of the rocky bodies that make up our solar system.

“The chemistry of the rocks, the types of landforms and the relationships between those characteristics provide us with knowledge about how our planet formed and evolved, and ultimately, we hope, whether or not habitable environments might have existed on other planets in the past,” said Jacob Elvin Bleacher, a NASA geologist who leads the Goddard Instrument Field Team.

What the instrument team has learned from doing analog experiments, particularly with astronauts such as International Space Station alumnus Barry Eugene “Butch” Wilmore, is that speed and ease-of-use are essential for space tools. Astronauts doing extravehicular activities, or EVAs, as excursions from the habitat are called, have limited oxygen and other resources, so device features such as instrument size, number of buttons, and the data display are crucial.

“What you don’t want is for an instrument to take two hours of crew time without the corresponding increase in scientific understanding that comes from looking at and interpreting the data,” said Young.

Time spent interpreting squiggly lines or scrolling through volumes of information, she noted, means less opportunity to walk farther away from the lander to make new discoveries.

Another seemingly benign consideration in instrument design that, through testing, turns out to be significant, is whether handheld instruments should have buttons. A device designed like a grocery-store price scanner makes for a comfortable handheld spectrometer shape on Earth, but in space, squeezing a trigger is not so straightforward. Because spacesuits are pressurized to resemble the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere, it takes more effort for astronauts to move against the extra force of their spacesuits, making small movements strenuous.

Below, check out highlights of the space-bound instruments NASA scientists and engineers are testing:

Mapping terrain with Terrestrial Laser Scanning:

Credits: NASA/Goddard

This tool uses light detection and ranging technology, or lidar, to map terrain in 3D, which allows explorers to understand the topography 200 meters (about 219 yards) around them.

Lidar maps surface geometry and elevation by shooting pulses of near-infrared light at millions of points on the ground and measuring how long it takes to bounce back. It then converts that time to distance based on the speed of light, and thus scans variations in elevation.

NASA’s terrestrial laser scanning device stands on a tripod, reaching 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall. The scanner rotates to capture data from all directions, while a digital camera snaps photos of the area to add color to the lidar maps. On top of the camera is mounted a GPS receiver that collects information about the scanner’s exact coordinates on the planet.

Lidar technology was developed decades ago and now is used extensively on Earth in fields ranging from volcanology, or the study of volcanoes, to driverless cars. Laser technologies similar to lidar, developed at Goddard, have been used on orbiters to measure the topography of planets including Earth. But terrestrial laser scanning has not been operated on any other planet yet. One future scenario involves rovers using this instrument to help human explorers find habitable tunnels below the surface of the Moon or Mars that were formed billions of years ago by flowing lava.

Probing rock chemistry with the Handheld X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometer

Credits: NASA/Goddard

This instrument can identify the elements objects are made of by using high-energy X-rays. It helps planetary explorers quickly evaluate (in recent tests, just two minutes) the composition of their immediate surroundings.

The fluorescence spectrometer beams X-rays when placed against a point on the surface of a planet. The incoming X-ray kicks an electron out of close orbit around the nucleus of an atom, triggering an electron from outer orbits to replace it, thereby returning the atom to equilibrium. This dance creates more X-ray energy, or fluorescence, which is picked up by a detector in the instrument.

Different elements in rocks and soils produce unique energy signatures that can be plotted on a graph or displayed in a data table. Scientists can determine the composition of an object based on the pattern generated on the screen of the instrument.

This spectrometer looks like a retail price scanner, weighing 4 pounds (2 kilograms). It is powered by a rechargeable lithium-ion battery, has a large-area silicon drift detector that senses and measures X-rays, and an anode tube that produces X-rays.

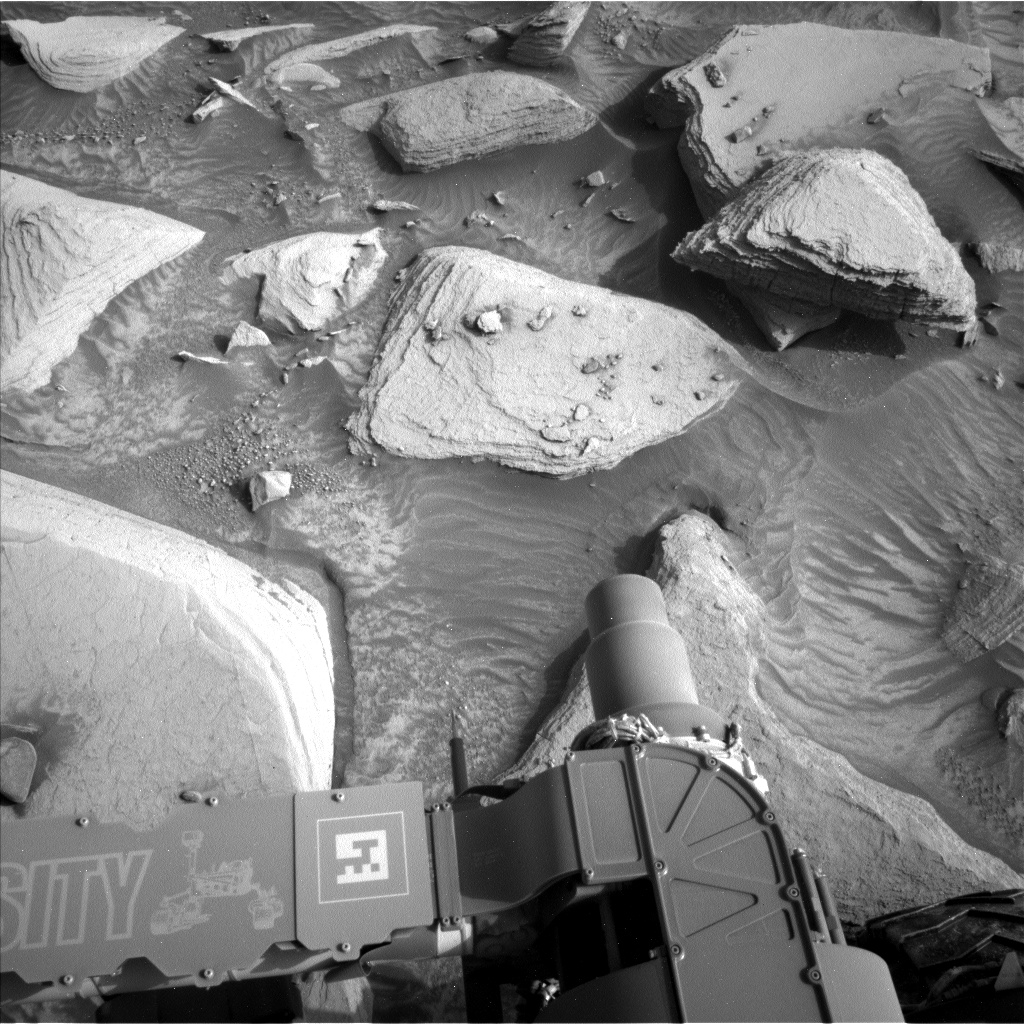

The X-Ray Fluorescence spectrometer, which has long been used in labs, has recently been adapted for handheld use. Industries including mining and archaeology use this tool. A similar technology has also been to space. Four rovers on Mars, including NASA’s Opportunity and Curiosity rovers, have used related technologies to explore their surroundings.

Identifying light elements with the handheld Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy instrument

Credits: NASA/Goddard

This instrument also identifies elements in rocks, but is particularly good at finding light elements. These are elements — such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen — that produce too little energy in response to a beam of photons to be detected by the handheld X-ray fluorescence spectrometer.

The laser instrument works by releasing a laser pulse of high-energy infrared light when held up to a rock. This heats up the piece of rock under the laser beam so much that it vaporizes into a plasma plume. The plasma releases light energy that’s sent to spectrometers that reveal the radiation released and absorbed. The resulting light signatures, which are revealed in peaks on a graph, correspond to the elements in the rocks.

NASA’s instrument team uses a laser tool that is handheld and weighs 4 pounds (2 kilograms). It’s powered by a rechargeable lithium-ion battery, and has two high-resolution spectrometers that together can identify a wider spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, from ultraviolet to infrared wavelengths.

Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy is used on Earth to identify the composition of rocks and minerals in various fields, including construction. But the instrument is also helping roving explorers in deep space. The ChemCam on the NASA’s Curiosity rover uses this type of spectroscopy to find the trace mineral boron on Mars, yet another clue that life could have existed on the planet.

By Lonnie Shekhtman

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.