Name: Jefferson Beck

Title: Earth Science Video Producer and Manager of the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) Communications Group

Organization: Code 130, Office of Communications, Office of the Director

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

As an Earth science video producer, I create products, mainly videos, relating to Earth science. I also manage larger projects working with extended teams. For example, I help make sure that a new data visualization supporting an agency-wide campaign is on track in terms of time and content. Is the piece telling the story we need it to tell? Does it fit in well with the greater campaign needs?

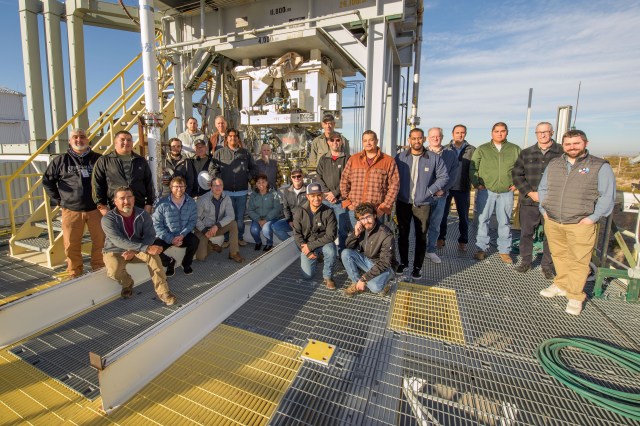

I am also the manager for the USRA Communications Group of about 19 people. I greatly enjoy representing our team of extremely creative and talented people. I am humbled by them.

What goes through you mind when you begin to create a video?

Often for me there’s a tension between the story I want to create and the story that is possible. I want to try to squeeze in all the content I would like to in one small package, typically 90 seconds to two-and-a-half minutes. On the other hand, I was a newspaper reporter for a small daily in Ohio, so part of me still wants to be able to capture the nuance and complexity that you can only get in a longer piece.

But I also know that the role of a video is different from a written piece in that videos are more to illustrate, engage and hook people into being interested in hopefully finding out more. So I have to free myself from thinking that I have to tell the whole story and rely on our world-class science writers to provide the depth that is hinted at in my videos.

What current large campaign are you supporting?

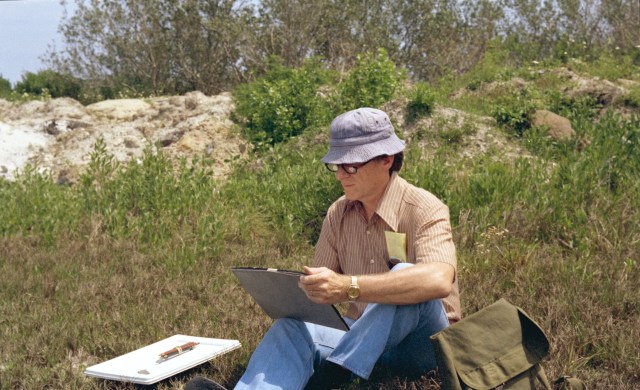

Right now I’m supporting the Earth Expeditions series of field campaigns which is an agency-wide push to highlight mostly airborne campaigns but also people collecting data from ships and people taking actual field measurements, boots on the ground. NASA has eight different field campaigns under the Earth Expeditions umbrella, one of which has 39 different research projects. These campaigns include missions looking at the world’s changing ice, the productivity of the oceans such as interactions between oceans and the atmosphere, air quality, and the health of coral reefs.

I support these missions generally and also help the agency determine the style and approach to capturing good imagery in the field.

What is your next Earth Expeditions fieldwork campaign?

In July, I went to the Fairbanks region of Alaska to visually document as many of the 39 science campaigns that I could that make up the Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE), which will study a variety of different ways in which the Arctic is changing, from vegetation to permafrost to methane to forest fires to Dall sheep.

During our 10 days in Alaska, I, along with science writer Kate Ramsayer, documented eight research projects, which was a lot to cover in a short time[GRC(SRA1] . We shot video, interviewed scientists and tried to get a range of footage that not only supports this particular mission but can be brought back for our producers to use to tell Arctic stories for years to come.

Are you familiar with Alaska?

In 1998, I lived in Fairbanks for a few months as a radio reporter for the University of Alaska radio station and the Alaska public radio network. I actually flew on a helicopter and landed on a Greenpeace ship that was documenting visible signs of climate change as reported by native communities along the Arctic coast. Even then, the coastal residents were reporting seeing changes in the distribution of sea ice and a change in the types of certain plants and herbs growing at different latitudes.

Are you an explorer at heart?

I love the snow. One of my favorite activities is cross country skiing. I will ski at 2 a.m. if that is the only opportunity to be able to ski before the snow melts.

I gravitate towards polar stories. I think I have caught a little of that bug that people have when they see the beauty in what can seem like a very desolate place. I think there is almost a thirst to see more. I have flown over the largest chunk of ice on the planet, Antarctica, at only 500 meters, and yet I still have this feeling that it is not quite enough.

So yes, at heart, I think I am an explorer.

Where else have you explored?

I am from Ohio. After graduating with a biology degree from the College of Wooster, I volunteered on a project to study and conserve sockeye salmon in southeast Alaska. I spent seven months living in a cabin in a field camp with two other people. We counted and identified the juvenile salmon as they headed down the outlet stream of Redoubt Lake to the open ocean for the first time. We had to count every three hours for two months, often in the middle of the night. Wearing head lamps, one of us stood in a freezing stream while the other held onto a .375 H&H rifle and kept an eye out for any hungry grizzlies.

We never saw any grizzlies while on the job. But on a hike one day, we saw a mama bear and her two cubs sliding down a patch of snow in a mountain valley and then running back up the rock face to slide down again.

At our next camp which was nearby, we ran into a lot of black bears. We constantly heard them around the camp. The head of that camp did not see the need for a gun and suggested that we throw rocks at any black bears that got too close.

What survival training did you receive to do field work in Alaska?

We had bear safety training. First, we learned how to use a rifle. We also received bear spray and learned to throw rocks at attacking bear. If actually attacked, we were to curl up in a ball and cover our head and neck. Better yet, we learned to make some noise and slowly walk away from the bear.

We also learned how to pilot a Boston Whaler boat from camp to town while avoiding a lot of nasty rocks just under the surface.

When did you become a writer?

After Alaska, I returned to Ohio where I was a general reporter for a small daily newspaper in my home town. It was a fantastic education in and of itself. I learned to tell a story from the ground up; I learned how to interview people; and I learned to look at the connections between the government, the private sector and regular citizens.

Why did you become a videographer?

It took me 12 years, but I gradually and eventually gave myself permission not to become a research scientist. I feel that I have always retained biology as a lens through which to see the world. Even as a writer, I gravitated towards science stories.

When I found the Master of Fine Arts program in science and natural history filmmaking at Montana State University, it tied all my interests together and really gave me a license to become a filmmaker. I lived in Montana for four years before coming to Goddard.

Where else have you traveled?

I’ve done fieldwork in Greenland and at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. I have also been to Colombia, where I visited the only wild population of hippos outside of Africa, on Pablo Escobar’s ranch. I have also seen Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, much of Europe, India, Guatemala, Patagonia and all 50 states.

How do you choose your adventures?

I really like to go somewhere where I think I can make an impact. On professional trips, I need to know that the work is important and the adventurous parts of it just come along for the ride. I am choosing my adventures more carefully now that I have a young family.

If you could go anywhere, where would you want to go and why?

I have not seen enough of the tropical rainforest. My wife, who is from Colombia and is also a biologist, talks of taking a trip to float down the Amazon, from high in the mountains, down the coast to Brazil, on small passenger boats.

What makes a good explorer?

Somebody who reads the environment without any perceptions and tries to allow that environment to change them more than they impact the environment.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.