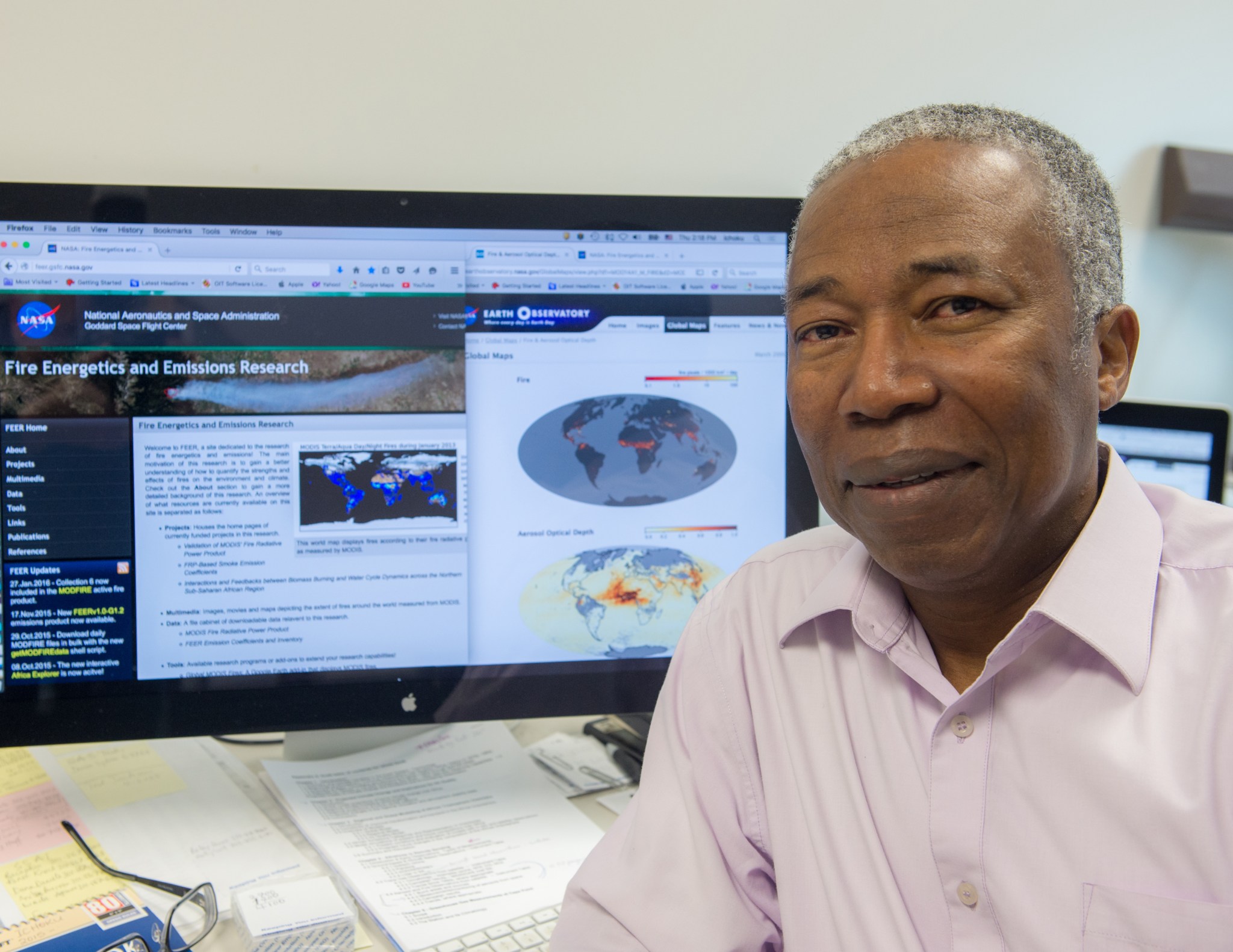

Name: Charles M. Ichoku, AST Climate and radiation (Code 613)

Formal Job Classification: Research physical scientist

Organization: Code 613, Climate and Radiation Laboratory, Sciences Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

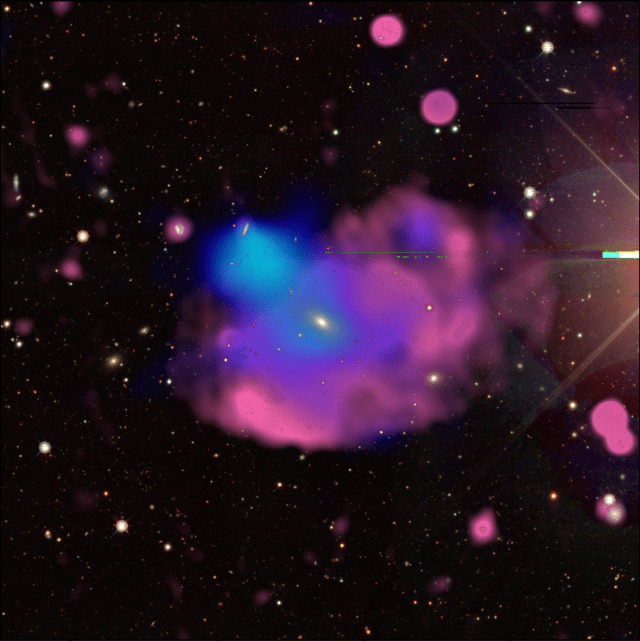

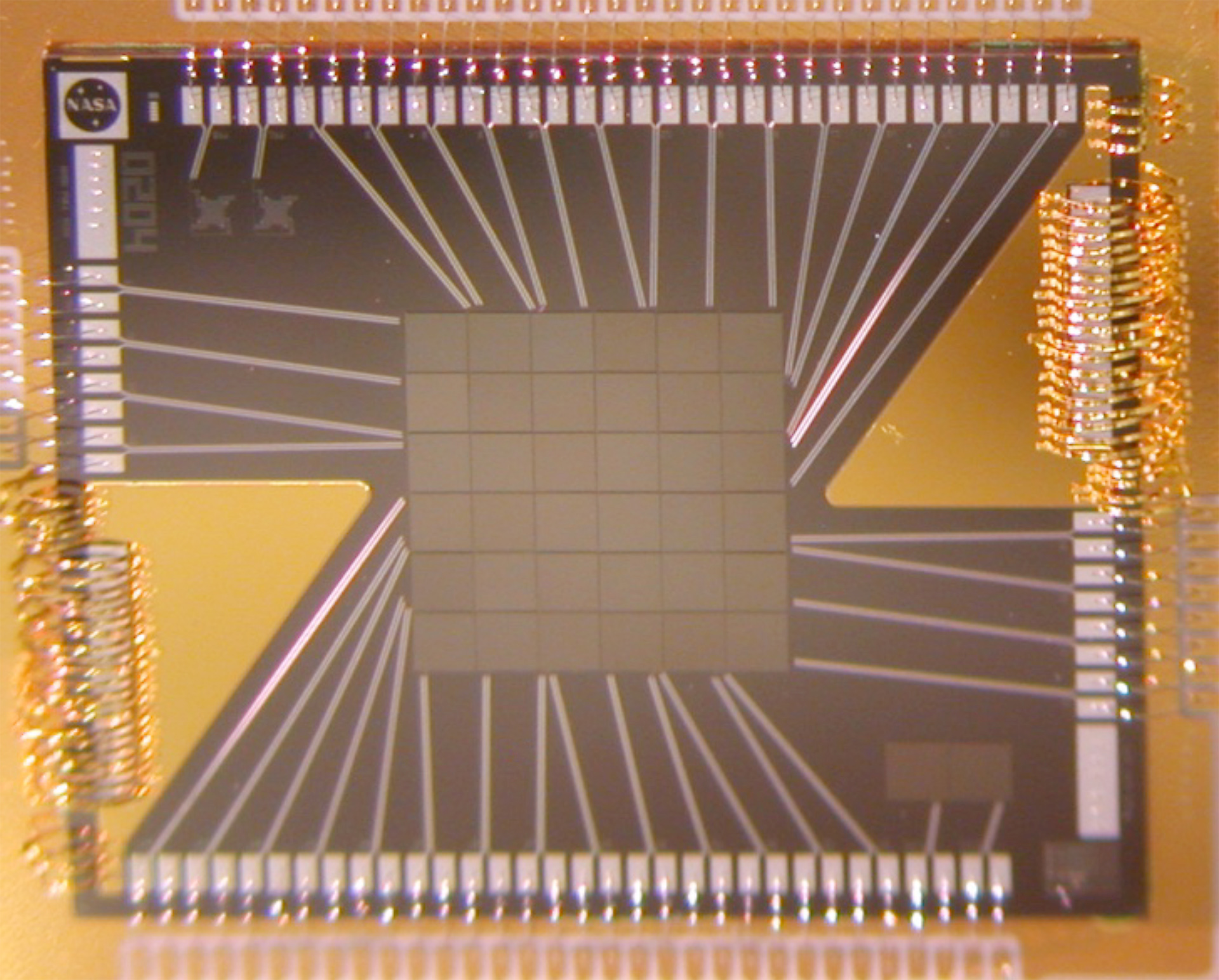

I conduct research about aerosols. My goal is to compare, understand and integrate aerosol retrievals from a lot of different satellite instruments. Examples include the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on the Terra and Aqua satellites, the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) instrument on Terra and the Ozone Monitoring (OMI) instrument on the Aura satellite.

I also work on remote sensing of wildfires and other types of global, open biomass burning. I measure the radiant heat energy released from these fires mainly from satellite observations, but also from sub-orbital platforms such as aircraft. I analyze the satellite fire measurements from the entire world together with the satellite aerosol measurements to estimate the smoke emissions from these wildfires.

Understanding wildfires is important because they affect our lives and environment in a variety of ways. Their emitted smoke is composed of many constituents, which can adversely affect air quality, human health, the environment and climate. Some of the constituents in smoke include black carbon, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane, nitrogen oxides and hundreds of other trace gases.

Do you work with teams and collaborate?

I generally work on several different projects at the same time. Each project is supported by a team of younger scientists and programmers who process and analyze the data. On a daily basis, they work with approximately one terabyte of data which can fill up about 200 DVDs or 20 times the full storage capacity of a 64 GB iPhone 6 or an equivalent digital camera. I apply the satellite measurements of aerosols and fires to study their impacts on the environment and climate on a global level and sometimes on a regional level.

I frequently collaborate with other researchers here at Goddard as well as from various national and international agencies, universities, and other institutions. Goddard is indeed an excellent place to work and I am enjoying it tremendously.

What is one of your current projects?

I’m currently conducting interdisciplinary studies of the effects of burning in Africa on the water cycle and drought. Farmers and pastoralists in the central and southern parts of Africa are burning for agricultural purposes including to clear the fields before cultivation, to burn the plant residue after harvest and to clear dead savanna to make way for new plants for their livestock. We estimate that a little over 50 percent of the global biomass burning occurs in Africa as man-made burning for agricultural purposes.

Please tell us about conducting field work with controlled fires.

In 2011 and again in 2012, I participated in field experiments in the Florida panhandle. In that series of field experiments called the Prescribed Fire Combustion-Atmospheric Dynamics Research Experiments (Rx-CADRE), which was sponsored by the multi-agency Joint Fire Sciences Program (http://www.firescience.gov/), we conducted prescribed burning to study fire behavior and emissions. Our group of about 100 set controlled burns and observed them using a variety of scientific instruments. We wanted to understand fires to better inform agencies that combat them and also manage and mitigate their effects.

Many of the scientists who participated in Rx-CADRE were also firefighters, a lot of whom worked for the forest service or the military. Other scientists came from various universities and government agencies including NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

For our study, some scientists first conducted fuel sampling to assess the amount and condition of the vegetation that will burn and then set up instruments on the ground to measure the heat release from the upcoming fire, the wind patterns and the smoke constituents. Other scientists simultaneously set up similar instruments on aircraft to overfly the area.

I’m one of the scientists who remained on the ground. I coordinated the ground-based measurements with satellite overpasses to ensure that the satellite instruments were actually measuring the same quantities measured both on the ground and from the aircraft to validate the satellite measurements.

A trained firefighter set the fire using a torch at the tail of an off-road vehicle or by dropping fireballs from a helicopter. The ensuing conflagration is formidable! It’s not something you see every day! Once the flames went up, the ground-based instruments started measuring the heat of conduction and convection as well as meteorological parameters. The airborne instruments measured the heat of radiation and the direction and composition of the smoke plume. All the data were recorded and stored for later analysis after we returned to our offices.

I have also been involved in fieldwork in Canada on airborne measurement of wildfires, in Chad on ground-based measurement of meteorological and hydrological parameters and in Israel on different issues including geology and airborne dust.

Please tell us about your childhood in Nigeria during the Biafran War.

I was born and raised in the city of Zaria, Nigeria, in western Africa. I was always interested in the environment. I like nature’s natural beauty, orderliness and peacefulness.

When I was about seven, civil war erupted in Nigeria between two major ethnic groups and affected the entire country. This was the Biafran War that raged from 1966 to 1970.

We fled the city because we were living in an area that was not of our ethnic group. We returned to the village where my parents were born, Nawfia, in southern Nigeria.

My native language is Ibo. However, I also understand Hausa, the language of my birthplace, where our family lived before the civil war.

How did you survive?

During those three years of civil war, we focused on surviving. When the war came down to the region where my hometown, Nawfia, is located, we escaped deeper into the more rural parts of the region, which had dense vegetation and not many access roads. Most of the residents of the entire Ibo-land had to move to hide in remote jungle villages to escape the war.

Even remote places such as the villages where we hid as refugees were shelled by aircraft and missiles. The troops couldn’t reach us, but their weapons could.

I was just a young kid. I did not fully grasp what was going on. I do not remember being scared as an adult would have been.

Our goal was to survive.

My parents worked hard and it was tough to find food. I have five siblings. Sometimes my parents did not eat and instead gave us their portions to make sure that we had something to eat. We ate all sorts of things that we would not normally have eaten. Sometimes relief organizations gave us food. Sometimes our parents worked on the local farms and were paid in food crops. The kids, including me, hunted small animals for food or picked the food crops left after harvest. We had water though from local springs and streams.

We also played as regular kids in spite of our difficult circumstances. We watched our Biafran military training. Many of us young boys were fascinated with the spectacle of the training and wanted to join the military, but we were too young to join.

We could not go to school for three years. Schools were used as refugee camps. We actually lived in one of them, so we had shelter.

How did you feel when you returned home?

Finally, one day in 1970, we heard on the radio that the war was over.

My family returned to our village, Nawfia. It was very overgrown with bushes. We could hardly find our way home, but it was very exciting to be home.

I was also very excited about returning to school. I had to work hard and skip a few grades to graduate high school with students my own age. Most of our high schools were boarding schools including mine.

How did you go from a refugee camp to college?

After high school, I worked for one year. I worked at a high school for six months and then at a bank for six months. I saved enough to start college.

I applied to several colleges and got into all of them. I decided to go to the one closest to home, the University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus. I got a scholarship after my first year, which paid for the rest of my education.

I studied surveying. I like the environment. I also made money during school by doing property surveys.

What did you do in the Nigerian National Youth Service Corps?

Nigeria has a National Youth Service Corps. This is not a military organization, it is more like the Peace Corps. Every Nigerian college graduate has to serve for one year following graduation. I was assigned to a private mapping company and helped map a state within Nigeria using aerial photographs. My job was relating the photos to what was on the ground. I did this for six months until the program ended. I then taught physics, math and surveying in a community college for the remaining six months.

Where did you do your initial graduate work?

I returned to the University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, for a master’s in photogrammetry and remote sensing. I also was a teaching assistant, which paid for my degree.

I was interested in remote sensing because I liked the idea of monitoring the environment from space and from aircraft. It’s beautiful to look at the picture of nature and of Earth from an elevated vantage point.

How did you get your first big break to study in France?

While at the University of Nigeria, one day I noticed an announcement on a bulletin board. The French government was offering scholarships to do a Ph.D. in France. I was overjoyed. I’d always wanted to go to France and had taken French in high school. I liked the language. I saw pictures of France and it looked so different and exotic. I applied and was accepted.

The program began with a one-year French immersion course in Nancy, France. I learned conversational and scientific French. We also worked in a lab to interact with scientists. We later toured France for two weeks as part of the program.

I got another master’s in remote sensing from the University of Paris, although the program was conducted at a remote sensing training center in Toulouse near the French space agency, the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales. After that, I moved to Paris to pursue my Ph.D. in Earth sciences at the University of Paris (now called Sorbonne Universités), Pierre et Marie Curie.

How did you end up working in the Negev?

One of my professors collaborated with an Israeli professor from the Desert Research Institute of the Ben Gurion University of the Negev who wanted a postdoctoral fellow. I did a post-doc with him in remote sensing applications for structural geology and tectonics of the Jordan Rift Valley and the morphology and phenology of the Negev desert. At the same time, I was an adjunct lecturer at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa.

I taught in English as some of the science is taught in English at the university. I spent four years in Israel, enjoyed my time there, and can still understand a bit of Hebrew.

How did you go from the Negev to Germany?

While in Israel, I became involved in field campaigns studying desert dust aerosol emissions and transport led by a German professor. At the end of the field campaign, the German professor invited me to be a visiting scientist in his lab at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany. I was there a little over a year and enjoyed my time there as well.

How do you get from Germany to Goddard?

I heard that Terra was about to be launched and that NASA Goddard was hiring people. I wrote to Yoram Kaufman, then a NASA Goddard scientist, who hired me.

Yoram was the real deal, an extremely accomplished scientist who was also a very kind, generous person. He was a true humanitarian. He was killed riding a bicycle in 2006, but is still cited extensively. Many of us are making our scientific careers by following through on some of his ideas. He conveyed ideas that were absolutely profound in very simple, elegant ways.

Does your work still take you abroad?

The Conference of Parties (COP) brings together on an annual basis a group of policy and government leaders from around the world interested in climate change. To prepare for COP21 that will take place in November 2015 in Paris, in July 2015, the organizers held a pre-conference in Paris for scientists of which I was one. I presented a paper about my research in Africa.

I have presented papers in various parts of the continental U.S., Alaska and Hawaii, as well as overseas in Australia, Austria, Canada, China, the Czech Republic, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Ghana, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Nigeria, Norway, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

What have you learned after traveling and living all over the world?

People are more or less the same. They all look for a better life. What you give is what you get. If you treat others well, they will treat you well. Hard work and perseverance produce very good results in the end. It is good to do and seek what is right, always, regardless of circumstances. I survived a war. I have lived in different countries and have been through different situations and circumstances. Even if you’re not well treated, be the example that you want to see. Also, stay calm no matter the situation and be self-controlled in all circumstances. Recognize and pursue promising opportunities and excellence – why not? And, of course, make every effort to deliver unquestionably great results.

I trust in God. I have faith in God. My perspective on life is derived from my trust and faith in God.

What do you do to relax?

I am blessed with a loving family and treasure family times and vacations. Every Saturday, Sunday and holiday, my wife and I take a walk in the park to be around nature which I still love. I especially enjoy elegant, well-tended parks.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.