Multiple launch pads, one long runway and dozens of facilities tuned to specific needs of aerospace operations give NASA’s Kennedy Space Center everything it needs to thrive following years of transformation work, said one of the architects of the ongoing transition.

The center, which at 144,000 acres is NASA’s largest facility by far, recently named a contractor to begin the transition from the current,1960s-vintage headquarters to a new one complete with modern office efficiencies and a footprint much kinder to the utility bills and environment.

The new headquarters will house a staff overseeing a much different space exploration scene than the one the original building was geared toward.

“Generally, big organizations take several years to change a culture and we’re halfway through that,” said Scott Colloredo, director of Kennedy’s Center Planning and Development directorate. “I think we’re embracing what we are doing as a center.”

The biggest difference is that NASA itself is not the only customer anymore. There also is a renewed awareness that Kennedy is capable of carrying out a greater diversity of tasks than those related to launching and recovering spacecraft.

The center also unveiled its 20-year master plan recently to detail what the center could become. Three years after the retirement of the space shuttle, planners say the demolition of older structures that are surplus to anyone’s needs and the reassignment of other facilities allowed them to look farther down the road at what Kennedy could become.

With its vast amount of land, infrastructure already in place and a work force geared toward technical, scientific and research duties, Kennedy can be thought of as the world’s only super-spaceport.

That’s where the multiple launch pads come in.

The vision of the center does not limit itself to Launch Complexes 39A and B, the pads used by Apollo and shuttles. The master plan points out the vast interest from companies wanting to use the Shuttle Landing Facility for space planes that would lift off on suborbital research and passenger-carrying trips. There is already a partnership with Starfighters Inc. to launch research experiment missions from the company’s fleet of supersonic F-104s.

“The runway is a pretty good place to start,” Colloredo said. “It takes more than that, but not much more than that.”

The unique runway, which is not only long but inside a protected enclave of land and airspace, has room to add more hangars or other infrastructure, too.

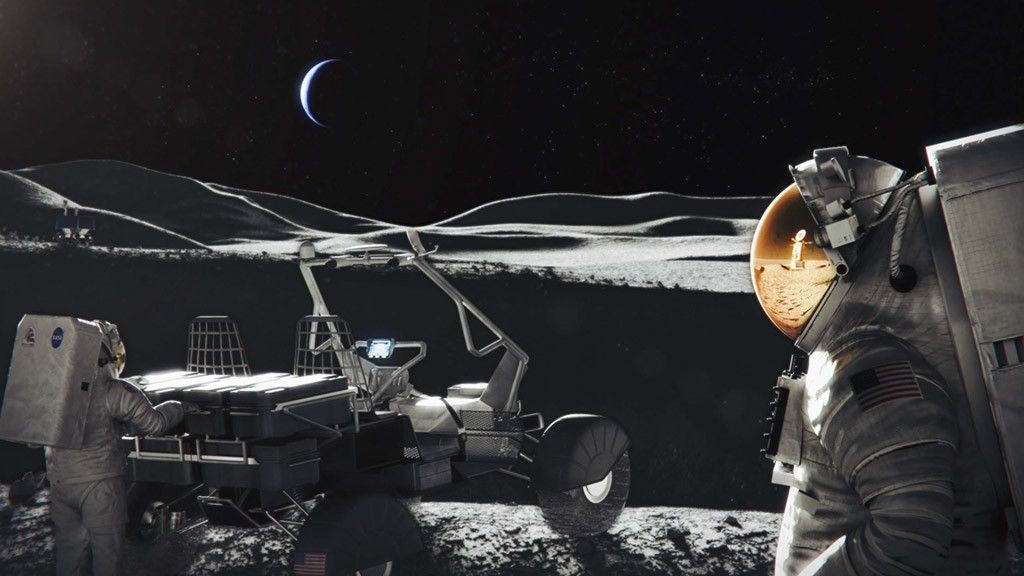

At Launch Complex 39, pad B is deep into refurbishment so it can host NASA’s Space Launch System deep-space rocket and Orion spacecraft beginning in a few years.

Pad A has been leased to SpaceX, the Hawthorne, California-based company behind the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon spacecraft. SpaceX anticipates launching its Falcon-Heavy rocket and human-carrying missions from 39A.

SpaceX also runs Launch Complex 40, where it has launched its Falcon 9 and Dragon cargo-carrying spacecraft to the International Space Station.

United Launch Alliance uses Launch Complex 41 for the Atlas V which has launched NASA interplanetary missions, commercial satellites and defense department assets. The pad is envisioned as the starting point for future human-rated spacecraft, too. Boeing and Sierra Nevada Corporation have signed on with ULA to launch their spacecraft on Atlas V.

Launch Complex 37, home of ULA’s Delta IV and Delta IV-Heavy, also figures into the plans because it can be used to launch science missions or flight tests like the one coming up later this year. A prototype Orion spacecraft will be launched on a Delta IV-Heavy for a two-orbit mission to evaluate some of Orion’s systems.

Many of these facilities have the potential to be used more by a greater number of programs and companies, Colloredo said.

Combining the capabilities of different Kennedy facilities would allow a company to perform every aspect of development, launch processing, launch and mission operations, recovery and evaluations without leaving the center’s boundaries in some cases.

“There’s a lot of synergy potential available for small launchers,” said Tom Engler, deputy director of Center Planning and Development.

The potential of the center is known throughout a variety of industries, but most of the recognition comes from aerospace companies now.

The center has inked partnership deals for several facilities including the high bay of the Operations and Checkout Building where Lockheed Martin manufactures and processes the Orion spacecraft for launch. Hangar N, a NASA structure at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, also is in use by another company now that its space shuttle-related efforts have ended.

Kennedy also is deep into negotiations for use of some of the iconic structures at Kennedy including the 3-mile-long Shuttle Landing Facility.

“All of these interested parties that want to come to Kennedy,” Colloredo said, “We want to make sure they can come here and grow together without working against each other.”

Boeing anticipates using Orbiter Processing Facility-3, one of the space shuttle’s former processing hangars, to process a new generation of spacecraft. The partnership for the building includes the company and Kennedy, along with Space Florida, an organization run by the state to advocate for Florida’s unique interests in spaceflight.

“Each of these transitions makes the next one easier,” Colloredo said. “OPF-3 is really a pathfinder in the whole transition of Kennedy from a single government program to a multi-user spaceport supporting numerous programs and companies.”

Changing Kennedy’s facilities is one thing, but the planning office is well aware that the changes embody fundamental culture changes at the center and throughout NASA, too.

“When you’re doing this kind of work, transforming not only Kennedy Space Center, but the whole way government works with industry partners, we have to be very careful how we do this so we can do it methodically,” Colloredo said. “I’d say the biggest adjustment is to move at the pace commercial industry wants us to move but still be able to transition assets effectively that have been bought and paid for by the taxpayer.”