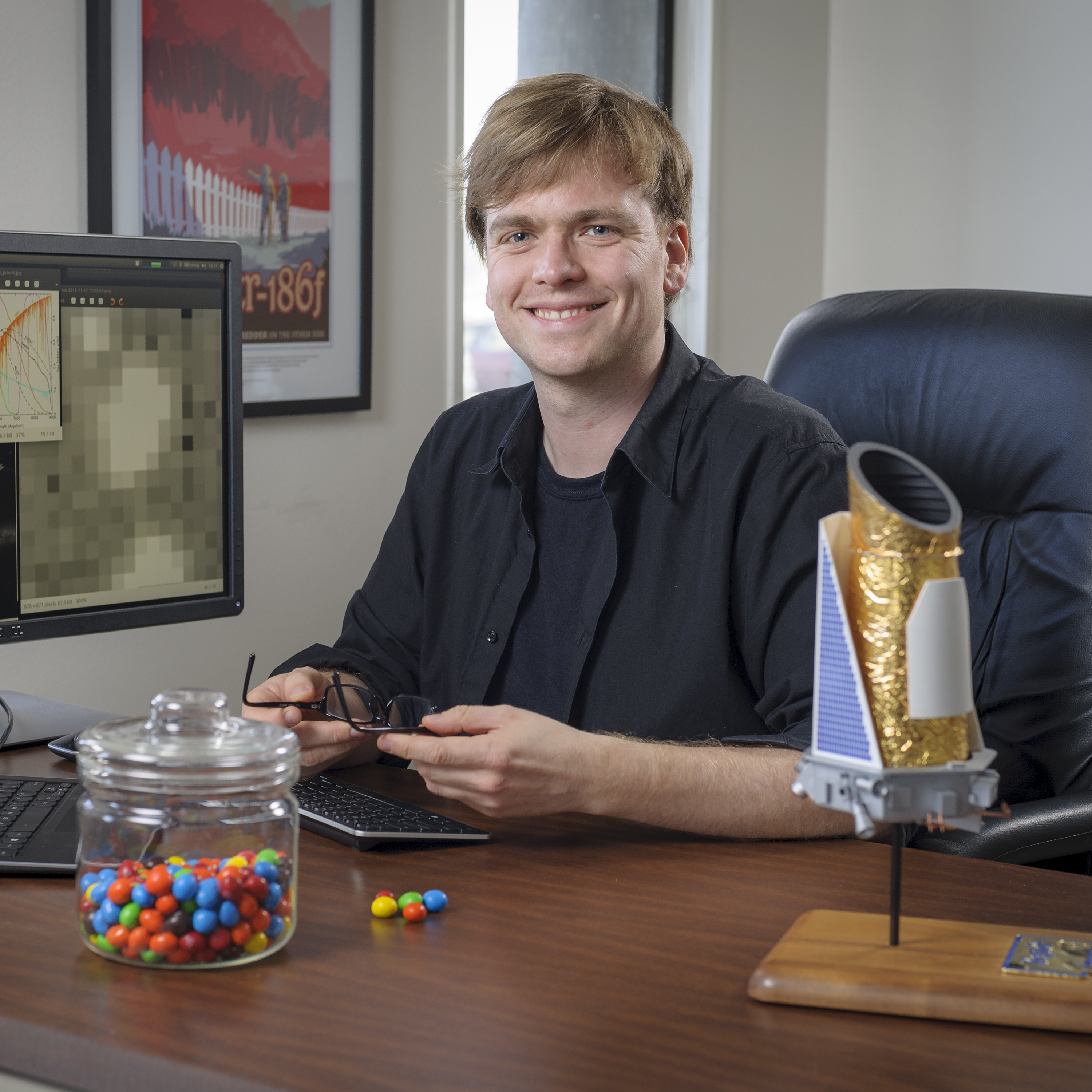

A conversation with Geert Barentsen, the Guest Observer Office director for the Kepler and K2 mission at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley. For more information on the Kepler Exoplanet Week, visit https://www.nasa.gov/kepler/exoplanetweek.

Transcript

Matthew C. Buffington (Host): Welcome to NASA in Silicon Valley, episode 47. Closing out this week for the Kepler and K2 Science Conference is our guest, Geert Barentsen, the Guest Observer Office director for the Kepler and K2 mission here at NASA Ames. Geert talks about growing up in Europe and how at a young age, he was already bringing people together for science and combining our collective knowledge to speed along discoveries. We talk about his work on the K2 part of the Kepler mission and how they have discovered new objects in our own solar system. As a reminder, check out our show notes for the link to our Exoplanet Week web page for everything Kepler and the science conference. Here is Geert Barentsen.

[Music]

Host: We always start it of with, you know, how did you get to NASA? How did you get to Silicon Valley? Tell us about you, Geert.

Geert Barentsen:So I came here this morning by bike, but that’s probably not what you’re asking, so…

Host: That’s very granular.

Geert Barentsen:No, it’s a long story. It’s really, I think the story is that basically, I was really poor at playing tennis and basketball.

Host: Okay, all right.

Geert Barentsen:That’s where it all started. So when I was a kid, I was doing those sports. I was terrible at it. What I was good at was computer programming. So at age eight, like 1991 or something, I was like programming my dad’s computer. Like, this is before the Internet.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:And so I was always interested in like nerdy things, like in science and so. So I had the incredible privilege of living close to this fabulous astronomy club in Belgium, which is the country I’m from.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:And this is where I got to hang out with all these like smart kids and other people that had my same sort of passions. So for example, what we would do is every summer, we would like rent this massive bus, load it with all the telescopes we could find –

Host: Really?

Geert Barentsen:– and like head to France for 10 days or indeed 10 nights and do astronomy.

Host: Oh, wow. It’s so, like from a young age – this is when you’re like eight, nine years old, you’re doing this stuff?

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, so I joined the club when I was 12, okay? And I got to be in this club which was like people that were in university and they were trying to do real science. And so one thing we would do in France was like count shooting stars. Now we didn’t just like mess around. We would record exactly the times we were looking at, the quality of the sky. We would record our peak rates.

And so we would then process the data during the day. Like, we didn’t really sleep. We would process the data, and we would like compute the flux, the number of meteoroids per second per square kilometer that would hit the atmosphere.

Host: And so, how do you even find something like this as a kid? I mean, were your parents like super into it? Or just, were you…?

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, as with many astronomers, my dad was actually a physics teacher.

Host: Oh, that helps.

Geert Barentsen:And so you know –

Host: If you had been a professional soccer player, then, that’d have been a different path.

Geert Barentsen:But even then, the fact I had access to a club which in, so Belgium has this amazing system where they have something like five or six astronomy clubs which actually the government funds. Not at a high level, like they pay one or two staff to run the club. But then you have a place to go and share your passion. And that really changed my life.

Host: So I’m guessing then, also growing up you watched like, you’d see stuff from the States like the shuttle, NASA shuttle missions. You’d see movies, stuff. Were you always kind of thinking that you would want to work in the space industry, whether it’s NASA or ESA [European Space Agency] or anything else like that?

Geert Barentsen: So my early passion in early age was computer science. I was really good at it. I was making websites when my elementary school teachers hadn’t heard of the internet in 1995.

Host: Really? Like Prodigy or something like that? Or America Online?

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, yeah. So I was like making these websites about astronomy, about my hobbies. I had a website at one point like in the ’90s where I was like hosting astronomy software I found online and I was writing tutorials and so on. And so like my obvious pathway – and I do think you should sort of study what you’re passionate about and good at – was to do computer science at university, which is what I did.

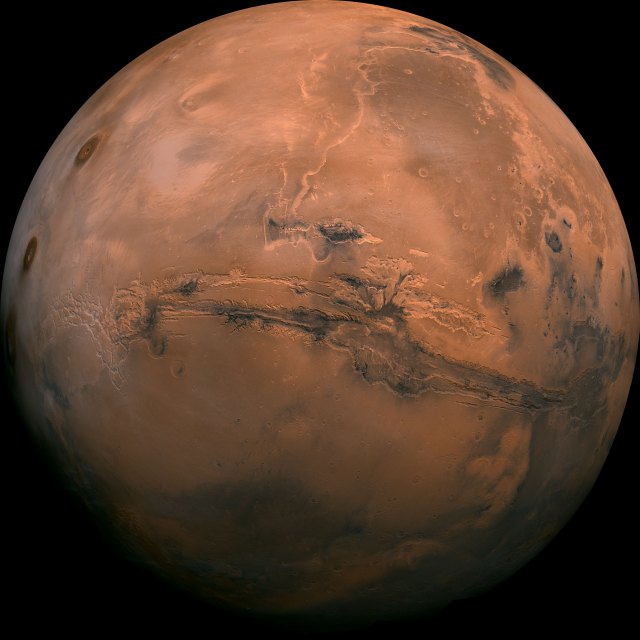

Now, I had this big passion for science as well. And my club had taught me that science was this ongoing endeavor and I could make contributions, because I was there in a field in France making contributions to science. Our data was used by professionals. But then I think what really changed things was January, 2004 when the Spirit rover landed on Mars.

Host: Oh really? Okay.

Geert Barentsen:This is before YouTube even existed, but the internet had evolved well enough that video streaming started to become pretty good. And on NASA TV, you could log in every day and watch the press conferences with Steve Squyres who was the instruments scientist [principal investigator] for the rovers. And NASA, you know, this is where NASA excels, right? NASA would be telling us, the general audience, exactly what was going on. They would share the images, share the pictures, share everything that was going on, be fully transparent. And I was so excited. The thrill of discovery was immense.

And then just a year later, in January 2005, second thing happened which is the Huygens probe arrived at Saturn with the Cassini mission. You know, Cassini’s still going?

Host: Still going, yeah.

Geert Barentsen:And landed in the, actually the, descended onto the surface of Titan. And so by that time, so I was still in university doing computer science, but you know, I was like on the internet, in this internet relay chat rooms, IRC chat rooms were the big thing back then.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:So I like, it was a bunch of friends there. And like, we had figured a way through connections, to get access to this data at the same time as the scientists because they were posted on some web server.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:So when the spacecraft came down, we were able to figure out how to open these binary files that came from the spacecraft and look at the images –

Host: Really?

Geert Barentsen:– before they were even in the news or before other scientists had seen them.

Host: Oh, that’s hilarious.

Geert Barentsen:But the thrill of discovery that this gave me was so immense that I was like, “Yeah, this is it. This is what I should do.”

Host: And so how did that leverage – for school – like how going from Belgium to the United States, how does that work?

Geert Barentsen:So I finished my degree in computer science and that all went well. I had the opportunity to do a Ph.D. in computer science, but it’s not what I wanted.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:So you know, by that stage, using like the shooting star science, I’d actually co-authored some papers, some scientific papers and I met some people. I went to these international meteor conferences where like amateur astronomers meet professionals and they, like, share their results. So I managed to end up in this traineeship program at the European Space Agency at the [indistinguishable] in Holland which is sort of the NASA Ames of ESA.

And so I got to work on this fabulous project. One of them was for Venus Express which was in orbit around Venus, which orbits Venus very closely and which really was taking close-up images of Venus’ atmosphere. They wanted to know what was going on, on the larger scale. They wanted to get the big picture of the atmosphere of Venus. And you could only do that from Earth using like a small telescope and a –

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:– and a web cam to actually get the whole atmosphere image. And amateur astronomers are actually very good at this. And with my background, I was able to set up this website and rally the amateur astronomy troops to like upload their images of Venus in real time to ESA.

Host: Oh wow. You’re crowdsourcing before it was a thing.

Geert Barentsen:Crowdsourcing citizen science.

Host: Yeah, really.

Geert Barentsen:And that is what I’ve – that’s been the team of my life. I’ve always been very interested in how normal people can sort of be part of the scientific endeavor, which I think is important.

Host: And then how does that end up all the way in California? It’s a long flight, yeah.

Geert Barentsen:So then, you know, that was great. I was doing more and more results. So I managed to get some Ph.D. offers. I went to Ireland to do a Ph.D. on star formation.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:So again I got the thrill of discovery of discovering new stars that had just formed in the last few million years, analyzing big data sets. I got to live in the city of Belfast in Northern Ireland which has some of the most beautiful and warm people on this planet.

Host: Oh, awesome.

Geert Barentsen:And I loved it. And you know, on sunny day, Ireland is this lush green hills –

Host: On a sunny day.

Geert Barentsen:– with, like dotted with white dots which are sheep it turns out.

Host: Nice.

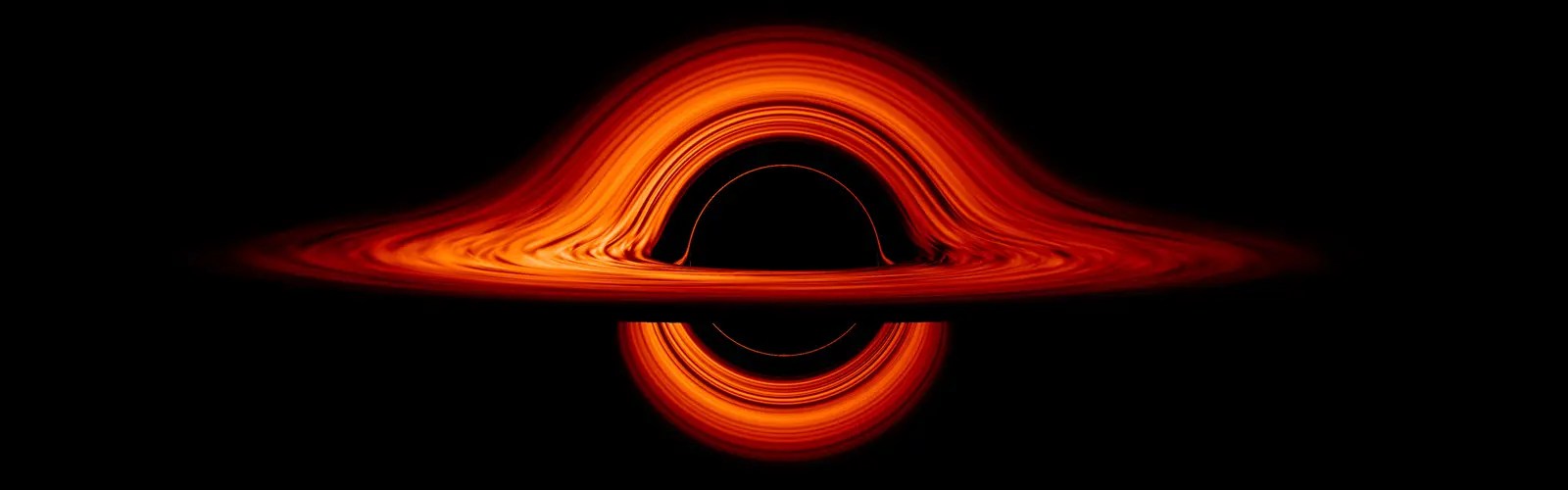

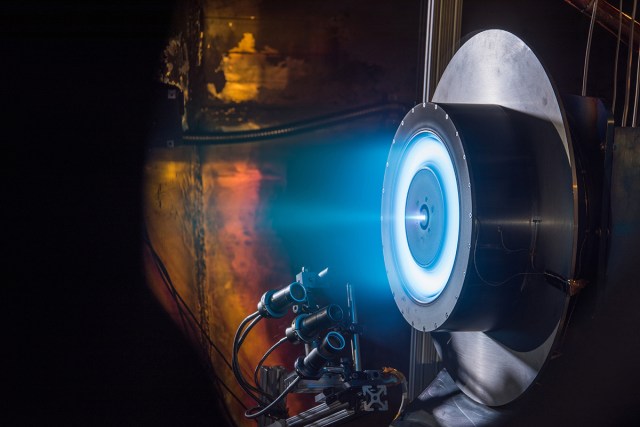

Geert Barentsen:You know, this led into a postdoc in England where I was still working on these data sets. But you know, academia can be pretty lonely. I was having lots of fun working with big data sets. We were measuring all the stars we found in the galactic plane toward the galactic center doing like these big surveys, big data. Again, that’s my computer science background. Mixed in with my Ph.D. in astronomy. And I was having lots of fun, but then something happened at NASA, which is that the Kepler mission – which is this incredible and perhaps one of the most transformative missions NASA’s ever done by discovering, you know, 5,000 planets orbiting other stars – suffered a malfunction. So back in 2013, it lost a second of its four stabilizers, reaction wheels.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:And if you look at headlines from that time, it says, “NASA gives up on the Kepler mission.”

Host: Oh, wow.

Geert Barentsen:And you know, Kepler had been a fantastic success at that point.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:It had changed the way I look at the sky because it had discovered –

Host: It rewrote, you know, textbooks.

Geert Barentsen:Right.

Host: It changed everything.

Geert Barentsen:Like suddenly we knew that there’s more planets than stars in our galaxy which means hundreds of billions of planets, right?

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:But so it suffered this malfunction and people thought it was over. But – and this is a fantastic feature of the people that built and operate Ames over at Ball Aerospace in Colorado and at NASA Ames here in Silicon Valley – they figured out a way to make it work.

Host: Wow.

Geert Barentsen:And this is insane. Because now we’re at the stage… So we have a new mission called K2 which uses the Kepler, this spacecraft – despite its malfunctions with the stabilizers – uses it in a new way. And has been incredibly successful. We are now at 250 publications. We’ve discovered, you know, 150 confirmed planets. We’ve done all this astrophysics with it. And we’re almost at the stage where people have forgotten how impossible this mission was.

Host: Yeah, like it shouldn’t exist.

Geert Barentsen:Just if any other two combination of reaction wheels had failed, or you know, the fact, where the antennas are on the spacecraft and all these things.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:You know, if you would go to the… You know Kepler was designed to look for four years to this one field in the sky to find, you know, Earth-like planets. Suddenly we were still able to use it, but we had to look at a different field every three months. We had a spacecraft that was less stable because our stabilizers had broken. This is like asking the astronauts on the ISS, on the International Space Station, to suddenly start orbiting the moon, paint the station pink and only eat chicken waffles.

Host: Yes.

Geert Barentsen:And it’s a bit hyperbolic but like… And so, it’s such an incredible testament to the NASA’s agility and like the agileness and incredible talent, the skills of the engineers on this project that they were able to make it work. Now this is where I come in. It’s that we had this brand new mission. And NASA, again to their credit said, “Okay, you seem to have a way to make this work. You have no results yet, but sure, here’s money for two years to make this work.”

Host: See if it can happen.

Geert Barentsen:And so Tom Barclay who you have interviewed at the time –

Host: Yes, for the fans of the podcast, this is one of our earlier interviews.

Geert Barentsen:He was right in the middle of figuring out, you know, “How are we going to make this work? Which targets are we going to observe? Which stars are we going to look at? How are we going to fund scientists to then use this data? How are we going to process the data?” Because the pipeline, you know, was made for a different type of data and everything.

And so he got money from NASA to run this mission along with the project scientists and so on. And so he needed a few people that would be able to hack this mission. Because the K2 mission is like this massive hack.

Host: Yeah, exactly.

Geert Barentsen:It’s really like, you know, Apollo 13 was a big hack. You know, saved people’s lives. You know, K2 is almost as big a hack. Because all the procedures we had in place for Kepler no longer applied.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:Procedures that were written over years and years in advance of the mission. So me with my computer science background, I was able to do programming. And with my broad view on astronomy of different kinds.

Host: I was going to say, your experience rallying the troops.

Geert Barentsen:Rallying the troops, you know, get the community to work together to make the best of the data even if it’s not, you know, the same quality as Kepler. It’s almost the same quality. So he tried to get me to join and I said, “No,” actually because my postdoc had just been extended for three years.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:But then he sat me down and he said, “You know, Geert, you know that in California, people have avocado trees in their garden.”

Host: Nice.

Geert Barentsen:“And by the way, this mission is going to be great because the reaction wheels that we have left, are going to survive.” He had this engineering data showing that.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:Like everybody was thinking that K2 might just live for six months or something. It was a huge risk, you know –

Host: Yeah, they didn’t really know. It was completely new territory.

Geert Barentsen:It was a huge risk to join this mission.

Host: Wow.

Geert Barentsen:And he convinced me. And he was right. He knew. He had this incredible feel for making it work. He stayed up, you know, 24/7 at certain times when the spacecraft was testing the new operations.

And so I took the risk and I joined. And it’s paid off tremendously because K2 is this incredible project which has now, you know, benefitted so many junior astronomers’ lives. Because here’s the thing — with K2, we were able to make all the data public straight away.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:Because we had these new operations and we needed everybody’s help to make this work and figure out how to analyze this data. And that was perhaps the biggest argument for me to join. Because I then thought back about the Huygens probe landing on Titan.

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:And you know, NASA allowing me to witness Spirit’s, you know, the Mars rover, exploration of Mars. And being able to work for a mission that would put all of its data public straightaway, would be such a great opportunity to be on the other end of this and inspire other people.

Host: Well, that’s the thing because it’s like, the Kepler telescope, space telescope takes in so much data, like it doesn’t make sense for NASA to hoard it for itself. Or even for our own astronomers to look at it. It’s just once you open it to the scientific community, you get results faster. Papers are written faster. You learn what is hidden, what knowledge is hidden in that data, like so much –

Geert Barentsen:We should never underestimate the creativity of humans.

Host: Yes, absolutely.

Geert Barentsen:Not just professional scientists, but everyone.

Host: And now, you glazed over it, because Tom has since moved over to Goddard, I believe.

Geert Barentsen:Tom did such a good job that he is now trying to make the TESS [Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite] mission a succession the NASA side. So TESS is this new mission that’s going to look at the brightest stars across the entire sky to find more planets. And I think part of K2’s legacy is that the test data is going to be fully public as well, instantly, which is so exciting.

Host: Excellent. And so, and then you’ve basically moved into that role.

Geert Barentsen:I moved into Tom’s role and I also, what I do as the Guest Observer Office director to use NASA English is to, you know, make sure we observe the right stars. So we get people to observe, to write proposals saying, “This is why we should observe this and that star.” We rank them using peer review. We then figure out which pixels we have to downlink to observe those stars. We’re limited on bandwidth. And then we make sure those data end up in the archive.

We give people the tools to work with that data. And we try to rally the troops. We go to conferences, tell them, you know, “We have this and that data. You can do this and that with it. Please, you know, join the fun.”

Host: So I remember when we first met, it was actually through a phone call. And I don’t know if you remember, but it was a while back. It was a journalist was asking, I believe it was about planets or planetoids like in our solar system, for some reason Kepler had picked up on –

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, with K2 we do –

Host: So K2 found some of the information about it.

Geert Barentsen:We do whatever the community tells us is the highest priority.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:So one thing, we’re now looking at the ecliptic plane which is the plane of our solar system. One thing that happens is we have these interesting distant objects called trans-Neptunian objects.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:Which are bit, bodies like Pluto, often a bit smaller but like in those far regions of the solar system. We look at them and we get this amazing space-space data from them which tells us the exact rotation periods. And from the rotation periods, we can infer something about their history. We can infer if they might have a moon or not. And indeed this object actually after the press interview you did actually turned out to have a moon.

Host: Oh really? Okay.

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, this is something we, I didn’t even tell you yet. Because the rotation period of this object was very slow, we had something that’s very common for bodies with a moon because moons tend to slow orbits.

Host: And is this all a part of like the Kuiper Belt? It’s that far out? Or how…?

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, pretty much. Yeah.

Host: Is it just, and it’s not discovering something new. It’s just understanding more about it like rotations –

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, these are objects we know. Like now since our last conversation, maybe a year ago?

Host: Yeah.

Geert Barentsen:Actually Kepler has discovered brand new Kuiper Belt objects. Just because people having been going through all the pixels we download and they say, “Hey, there’s this thing moving. I wonder what it is. Hey, it’s not in any database.” And so this thing now has a number which means that it’s sort of being followed up now by other telescopes and it’s a brand new object in the solar system. You know?

Host: And we alluded to it previously, but perhaps go into a little bit of detail if anybody is just joining the podcast, this is their first one that they’ve ever listened to. Talk a little bit about the difference of what, the point in the sky that Kepler looked at, versus what K2. You said the elliptic [ecliptic], but explain a little bit what that means.

Geert Barentsen:So the Kepler spacecraft looked for four years toward the constellation of Cygnus the swan – which you can see with the naked eye quite easily in the summer night sky – to find planets on Earth-like orbits, around Earth-like stars. And you need to look for several years to see them because like our Earth only orbits every year.

Host: Yeah, yeah, 365 days. You know, you have to wait.

Geert Barentsen:You have to wait. So if you, we want to see like three transits, so three times watching the star pass in front of the – sorry – watching the planet pass in front of the star. If you see that sort of three times, that starts to give you a pretty good idea that it might be real and not noise. So you have to look for three or four years to get that data.

Now with K2 we can no longer do that. We can only look for three months at a time at a field because of the new way that we are using solar radiation pressure to balance the spacecraft.

Host: And that field changes.

Geert Barentsen:And that field changes every three months. So like right now I have to deliver the targets, the stars, the pixels that we want to downlink for the next campaign by next Thursday for example. So that’s part of my job. In fact we’re going to start a brand new field which has a really cool object in it. It’s called Wolf 359.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:It is the fifth closest star system to Earth. It’s eight light years away which is incredible close for [stars].

Host: Yes, considering.

Geert Barentsen:You know, finding a planet around Wolf 359 would be fantastic. Because having planets really close to our own sun gives us the best opportunity at using NASA’s other facilities like the James Webb Telescope in the future and the Spitzer Space Telescope to really try to understand the atmospheres of those planets by looking at light passing through the atmosphere of those planets for example.

Host: Talk a little bit about the campaigns. How do campaigns get formed together? How do you guys decide what you’re looking at? What you’re not going to look at?

Geert Barentsen:So we have to –

Host: I mean, how often are the campaigns, even?

Geert Barentsen:So we do campaigns, as we call them, three months at a time which is the maximum amount of time we can stare at a field without the sun starting to shine either on the electronics at the back or on the inside the tube, the telescope tube, at the front.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:So we can do for three months. We have to look in the ecliptic plane. Because if we orient our spacecraft just in the right way towards the sun that the solar radiation pressure is balanced on the solar panels – this kind of complicated geometry – it yields us with a field. At a given time, we can only look at that one field.

So we just look. You know this, “We’re in this time of the year, this is where we are going to look.” We announce this field to astronomers and then they’ll tell us, “Oh, you know, these are the objects we want to look at.”

Host: Oh, cool.

Geert Barentsen:And so this is a very careful process. We want to make the best use of this unique space telescope. And so we, like a year in advance, people start writing proposals. We send them out to other astronomers who rank them and we make a ranking of the highest priority things to observe. And that’s how we get these campaigns.

So every three months we have a new campaign. And it takes us about three months to then process the data and publish them online for everybody to use.

Host: All right. So this might be a little bit in the weeds, but I’ve seen some of the illustrations and things that the Kepler team has put out. And you think of like the space in the sky that it looks at. It’s not like it’s, “Here’s a big square or a big circle where we’re looking at.” Sometimes they have it, like the design is like, there’s like a couple squares. It’s almost like —

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Host: Why? Yeah, it almost looks like a Rubik’s cube but with missing corners or something. So why is it like that?

Geert Barentsen:So you can think of the Kepler space telescope as a really big DSLR – like a really big digital camera that you can buy in a shop. Except ours is like really big. You know, it’s many meters high. So our camera has 100 megapixels.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:Now, it’s in deep space. This spacecraft is 1 AU [astronomical unit], or indeed, 150 million kilometers away from Earth. It’s the same distance as the Earth is from the sun. At those distances, it takes huge antennas to get the data back. And even then we only do like a few megabits per second. And so we cannot downlink 100 million pixels –

Host: All at once.

Geert Barentsen:– for like, you know, some pixels we observe with one minute cadence. So every minute, we observe the intensity of the light in that pixel. We cannot download all those pixels. Because we have to turn the spacecraft’s antenna to Earth and it would take months to download all those data.

So what we do is we figure out, “Which are the most interesting pixels?” So for maybe 20-30,000 stars that we think are the most interesting, we download the pixels around those stars. And so that’s why, when you look at the actual data from K2, you see all these small like postage stamps where we just have collected the light from those, you know, 20-30-40,000 stars. Because the community, the astronomers in universities have told us that those are the stars that are most interesting for their [faraway] science cases.

Host: Wow. And as you mentioned how far Kepler is from us, basically the way it works – and correct me if I’m wrong is – you know, the Earth circles the sun and it’s almost like Kepler kind of follows behind the Earth.

Geert Barentsen:That’s right. Kepler’s in this Earth-trailing orbit.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:What that means, it is on an orbit that is very similar to Earth’s around the sun except it’s on a slightly longer orbit.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:So Earth revolves around the sun every 365.24 days. Kepler has something like a 370 day orbit.

Host: Okay.

Geert Barentsen:That was launched eight years ago, so over time it has started drifting away from the Earth. And so now it’s about, you know, 40 days behind the Earth, trailing the Earth, which leads to this big distance. It keeps going, getting more and more and more. And eventually it’s going to disappear behind the sun. And it’s actually going to come back and eventually the Earth will catch up again with Kepler.

Host: Oh, wow.

Geert Barentsen:It will still be quite far, but Bill Borucki who is the original principal investigator of the mission actually is trying to convince young people that they should step up and try when Kepler goes back in our vicinity in the 2040s or something to actually go and get it and put it in the Smithsonian.

Host: Absolutely. That just seems like an obvious thing.

Another thing that is very exciting about this mission as I said is all the data is public. So we’re able to do really cool and new things. For example, last month I travelled to Australia, to a big observatory there.

Because the BBC which is a British public broadcast, it has this format called “Stargazing Live.” It’s a live TV show that goes out three nights in a row, and for one hour they put real astronomy on primetime television. It’s a fabulous concept which –

Host: Oh, wow.

Geert Barentsen:– and it’s actually made by astronomers. Actually, I can’t believe they get away with it in primetime but it’s in part because it’s live. So they actually sold this concept to Australian television now. So for three nights in a row, we made a show on Australian television where a million viewers were educated about astronomy. They showed the constellations and so on.

Now as part of the show, which is presented by a professional astronomer, we did this project where we set up a website called Exoplanet Explorers. With help from scientists at the University of Santa Cruz near Silicon Valley. And we told the viewers, the Australian public, “Hey, why don’t you help us out? This is what we’re doing. This is the light signal we’re looking when a planet transits in front of the star. We’re looking for this signal. We have just downloaded data for 30,000 stars two weeks ago using antennas in Australia which is part of the Deep Space Network. Please help us figure out where the new planets are.”

So that’s what we told the viewers for like five or 10 minutes live on air. Then the next show, we give them an update, “Oh, this is so far what you’ve been finding. We’re looking into your results.” So on the third show, the third night of this live TV show, we were able to announce the discovery of a new solar system, 200 light years away, with four planets in it. And the first person to have classified that system, to have pointed out that that system existed was a car mechanic from Darwin.

Host: Oh that’s hilarious. Awesome.

Geert Barentsen:And so the TV producers actually rushed a TV crew to him.

Host: Well of course. That’s golden.

Geert Barentsen:So they interviewed him live on air, “How do you feel about having discovered new planets?” And so on. So now I have this paper in my hand. So this is just last month, right? So in the meanwhile, we’ve written up this paper announcing this exciting discovery. And so Andrew Grey who is this car mechanic from Darwin, Australia is on this paper.

Host: Oh, that is hilarious.

Geert Barentsen:And so we are trying to do this thing where we try to really open up the process of scientific discovery.

Host: Absolutely, yeah.

Geert Barentsen:Because you know, in my grand moments, I really think this can have long-lasting consequences. And so we’re playing, I’m personally very interested in the coming months and years to really figure out how we can do more of this type of thing.

So I started going around Silicon Valley giving this talk called, “How to find a planet,” where I go to people’s houses, often, you know, engineers. But usually no astronomical experience. And I tell them, “Here’s the code you need to find planets.” And I let them, I show them data and we go through it together and maybe 30 minutes later they have discovered a planet.

Host: Excellent.

Geert Barentsen:So.

Host: But for anybody who’s listening, if you have questions, anything for Geert, we are @NASAAmes. Also, the Twitter handle @NASAKepler is another, is one of our sister Twitter feeds that we always share information back and forth. And we’re using the #NASASiliconValley so you can send any questions our way, we’ll flip it on over to Geert for responses.

Geert Barentsen:Yeah. And specifically for the K2 mission, there’s a hashtag called #K2Mission.

Host: Oh excellent.

Geert Barentsen:And what’s going on right now today is like people have been finding this star with strange behavior. People are discussing that star in the recent data right now. And it happens all the time on this hashtag. Whenever there’s new data coming down, people are using, astronomers are using this hashtag to share in real time what’s going on.

Host: Is that a reference to the Tabby’s Star?

Geert Barentsen:Tabby’s Star right now is doing weird stuff.

Host: Oh, because we have some stuff in the works for that one. But no spoilers.

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, yeah. No spoilers. But it’s exciting.

Host: Excellent. Well, thank you so much for coming over.

Geert Barentsen:Yeah, it’s fun.

[End]