Apollo 17 - Eugene Cernan working at the Rover.Image Credit: NASA/Jack Schmitt (assembled by Mike Constantine)

- Before Apollo -

Kennedy’s Decision

Image Credit: NASA

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced before a special joint session of Congress the dramatic and ambitious goal of sending an American safely to the Moon before the end of the decade. Kennedy felt great pressure to have the United States "catch up to and overtake" the Soviet Union in the "space race." Yuri Gagarin had become the first human in space on April 12, 1961, greatly embarrassing the United States. While Alan Shepard became the first American in space on May 5, he only flew on a short suborbital flight instead of orbiting the Earth, as Gagarin had done. Kennedy wanted to announce a program that the U.S. had a strong chance at achieving before the Soviet Union. After consulting with Vice President Johnson, NASA Administrator James Webb, and other officials, he concluded that landing an American on the Moon would be a very challenging technological feat, but an area of space exploration in which the U.S. actually had a potential lead.

Video Excerpt from an Address Before a Joint Session of Congress, 25 May 1961

Starting from Scratch

There was no known way to the Moon. NASA had to learn everything about it. As Robert Gilruth, head of the Space Task Group and later NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, wrote in “Apollo Expeditions to the Moon”:

Flying man to the Moon required an enormous advance in the science of flight in a very short time. . . . Rendezvous, docking, prolonged weightlessness, radiation, and the meteoroid hazard all involved problems of unknown dimensions. We would need giant new rockets burning high-energy hydrogen; a breakthrough in reliability; new methods of staging and handling; and the ability to launch on time, since going to the Moon required the accurate hitting of launch windows. Man himself was a great unknown. At the time of the President's decision we had only Alan Shepard's brief 15 minutes of flight on which to base our knowledge. Could man really function on a two-week mission that would involve precise maneuvers, including retrofire into lunar orbit, backing down and landing on the Moon, lunar take-off, midcourse corrections on the way home and, finally, a high-speed reentry into Earth's atmosphere, performed with a precision so far unknown in vehicle guidance? . . . . Not only would all these things have to be done in the short time available, but many would have to be worked out at the beginning, during what I have called "the year of decisions."

Project Mercury

At the time of Kennedy’s announcement, America’s first human spaceflight effort, Project Mercury, was already underway.

At a press conference in Washington, D.C., on April 9, 1959, NASA introduced the Mercury Seven to the public. The press and public soon adopted them as heroes, embodying the new spirit of space exploration. During the five-year life of the project, six human-tended flights and eight automated flights were completed, proving that human spaceflight was possible. Once Shepard’s flight was successful, Kennedy made his decision and Mercury focused on initial objectives needed to get to the moon.

Mercury astronauts, the “Original Seven.” Front row, left to right: Wally Schirra, Deke Slayton, John Glenn, Scott Carpenter; back row, Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, and Gordon Cooper.Image Credit: NASA

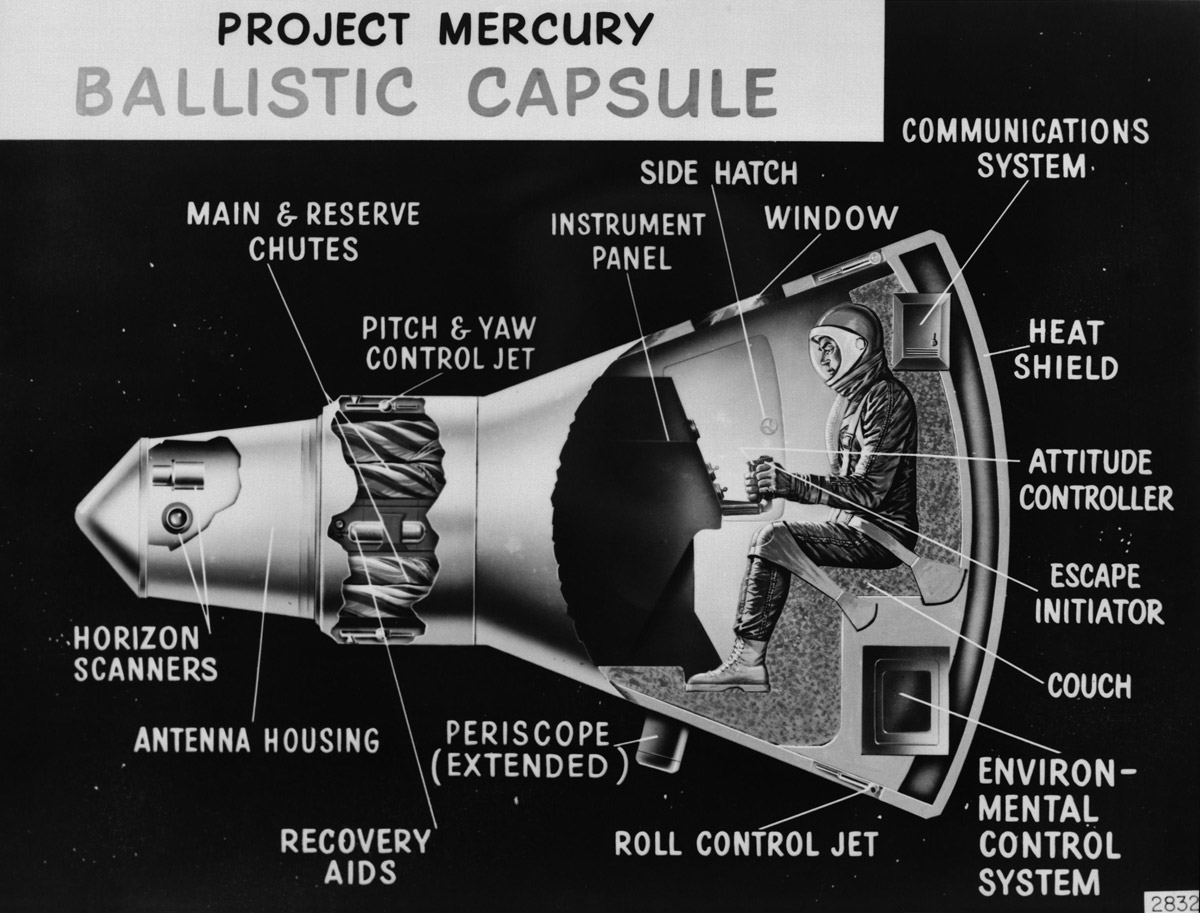

This cutaway drawing was used by the Space Task Group to explain the Mercury ballistic capsule to visitors at the first NASA inspection.Image Credit: NASA

Astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr. is rescued by a U.S. Marine helicopter at the termination of his suborbital flight May 5, 1961, down range from the Florida eastern coast.Image Credit: NASA

Project Gemini

Just as Orion and the International Space Station are helping NASA learn how to go to further into space for longer missions, the Gemini program defined and tested the skills NASA would need to go to the Moon in the 1960s and ‘70s. Gemini had four main goals: to test an astronaut's ability to fly long-duration missions (up to two weeks in space); to understand how spacecraft could rendezvous and dock in orbit around the Earth and the moon; to perfect re-entry and landing methods; and to further understand the effects of longer space flights on astronauts.

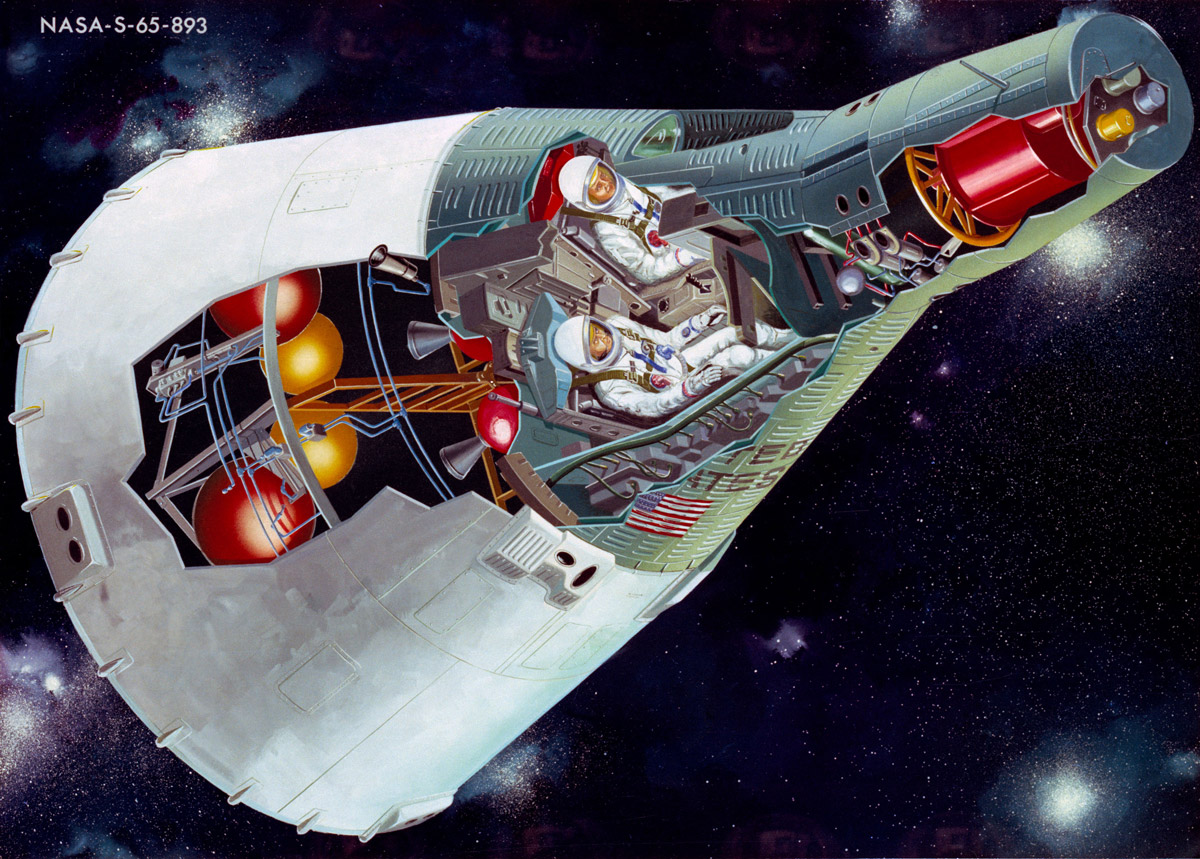

This artist's concept of a two-person Gemini spacecraft in flight shows a cutaway view. Gemini paved the way for Apollo, and had four main goals: to test an astronaut's ability to fly long-duration missions (up to two weeks in space); to understand how spacecraft could rendezvous and dock in orbit around the Earth and the Moon; to perfect re-entry and landing methods; and to further understand the effects of longer spaceflights on astronauts.Image Credit: NASA