By Brian Dunbar, Internet Services Manager

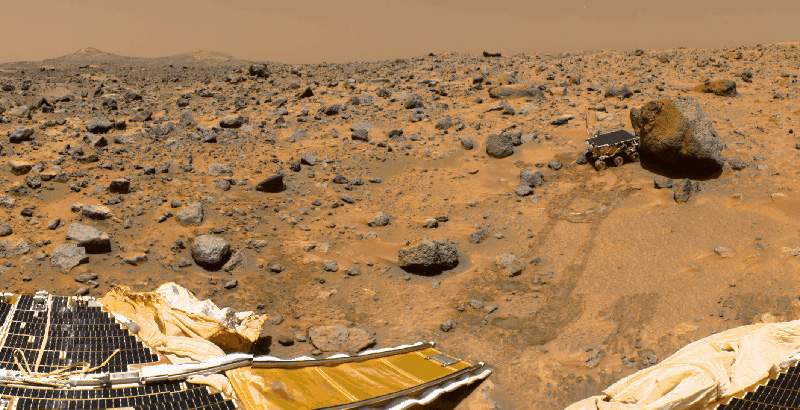

Twenty years ago, NASA landed a little rover on Mars . . . and blew up the Internet. As people clamored for pictures – overwhelming servers and bringing network traffic to a standstill – it became obvious that something fundamental had changed on how people expected to get information about NASA missions.

Image Credit: NASA

NASA, through its Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, had begun to release information online following Voyager’s encounters with Uranus and Neptune in the 1980s.

“When I arrived at JPL in 1985, I was already active in some of the online networks of the day such as CompuServe, so distributing pictures and information about NASA missions that way seemed natural,” said former JPL public information manager Frank O’Donnell. “Also, Ron Baalke at JPL was very active posting information to Usenet, the Internet-based system of newsgroups. At the end of the '80s, I established a dialup bulletin board system at JPL, which members of the public could dial into directly to download pictures and text files.”

Then, in 1993, came the discovery of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, and astronomers’ realization that it would hit Jupiter in July 1994. By then scientists were communicating by e-mail, transferring large files around the world and posting their work for discussion on the nascent World Wide Web. Now they were using those tools to plan worldwide campaign to observe the collision

NASA’s public affairs office followed suit, scheduling briefings throughout the encounter. (The comet had fragmented into numerous pieces that would arrive at Jupiter over several days.) The schedule published the time images were expected to be received and when they would be discussed on NASA TV.

Naturally, Internet users started banging on NASA websites a few minutes before the pictures were scheduled to be downlinked, unable to wait until the scheduled release time. As Philip C. Plait wrote in “Bad Astronomy”, “. . . the web nearly screeched to a halt due to the overwhelming amount of traffic as people tried to find pictures of the event from different observatories.”

The excitement wasn’t limited to the public. Scientists found themselves doing their work live on NASA TV, as this clip from a National Geographic special shows. By coincidence it was also around this time that NASA’s Office of Public Affairs announced that it would no longer mail news releases to reporters, but would instead distribute them online.

Shoemaker-Levy made it clear to JPL they would have to prepare for something even bigger with Mars Pathfinder. Webmaster David Dubov told the New York Times shortly after the landing that he estimated the site would be receiving 25 million hits a day. (A “hit” is a request for information from one computer to another. On the web, a hit can represent the transfer of a picture, text or other page element. In the case of Pathfinder’s deliberately stripped-down site, each web page comprised a few hits.)

Dubov and JPL engineer Kirk Goodall would later revise that estimate to 60-80 million hits a day, traffic that would crash JPL’s networks if the servers were hosted there. Goodall set out to build a network of mirror sites that could take the traffic off JPL’s networks. Working with other U.S. science agencies, and ultimately corporations and Internet “backbone” providers, he did just that. (In other words, JPL crowd-sourced their solution a couple of decades before anyone knew crowdsourcing was a thing.)

And the solution worked. The site took 30 million hits on landing day, July 4. On July 7, the first weekday after the landing, the site got 80 million hits. In comparison, the year before, the chess match between Gary Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue computer peaked at 21 million hits, and the Atlanta Olympics website had topped out at 18 million hits on one day.

“One of the biggest changes with Mars Pathfinder was that it was the first mission that fully embraced the Internet as a primary way of getting out information to the public,” said O’Donnell. “Before Pathfinder, the prevailing thinking was that eight-by-ten photo prints were the product needed for the public at large.”

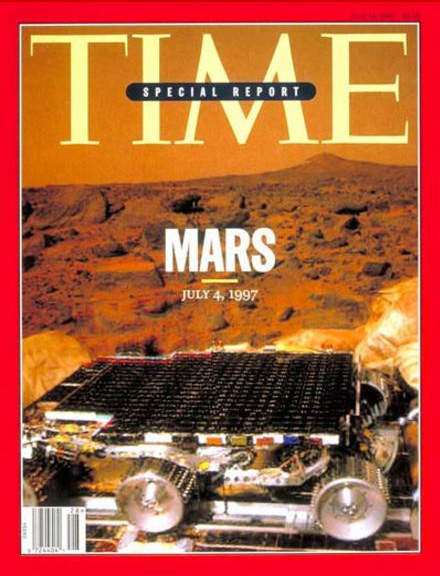

It’s worth remembering how the public got to see NASA images before the Internet era. NASA teams would review the raw images, select a few and distribute them as physical prints at news conferences. Media had to be in attendance at the conference to get a copy. Most newspapers and TV stations had to wait until a wire service had scanned the image and sent it out over their proprietary network.

Most people might see a new image every day for a few days. A week later there might be a few more images published in weekly news magazines. Maybe six or eight months later, a magazine like National Geographic might publish a long story with a dozen or more additional images. Most people never saw more than a handful of pictures from NASA missions.

Image Credit: NASA

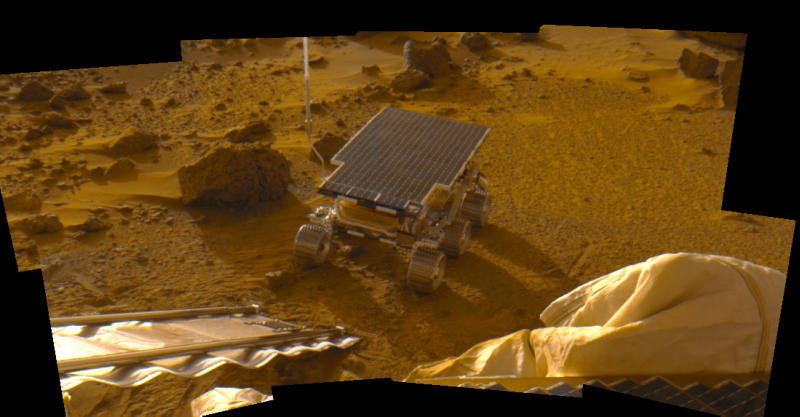

The Pathfinder team had to take “photo prints and scan them in order to post digital files online,” said O’Donnell. “Pathfinder's teams committed to releasing direct-to-digital files very quickly.”

“And the public loved it.” he added.

“I remember sitting at my desk clicking on picture after picture,” said Bob Jacobs, now NASA’s deputy associate administrator for communications, but then with the Associated Press. “I could see so much more from this mission than it ever had before, and I came back day after day.”

Not everyone was happy. IT staffs around the world found themselves dealing with unprecedented amounts of traffic on their local networks, sometimes to the breaking point. In France, where the same networks were carrying telephone and Internet traffic, the government took the unprecedented step of asking people not visit the websites, since it was affecting phone service. At NASA Headquarters, which had an indirect Internet connection through a NASA center handled traffic to its web servers through the same “pipe” as business services, saw very slow performance for e-mail and other business operations on July 7.

Mars Pathfinder changed forever how the public expected to get information on NASA missions, and on any other live event. Instead of waiting for news reports, the public expected to join in as the event happened and see results in real time. By the time NASA’s next rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, landed on Mars in 2004, NASA had moved its web infrastructure to into a commercial data center and added a commercial caching network. The change allowed NASA to handle even more traffic, 109 million hits in 24 hours, including having 50,000 people watching NASA TV’s coverage of the landings via webcast.

NASA online offerings continue to evolve. Now nearing the end of its mission, Cassini has been sending back raw images from Saturn and its moons since 2005, and they have been made immediately available to the public. NASA’s Mars missions have similar sites. The Hubble Space Telescope has made thousands of images available online. With the advent of social media, people can share and talk about images immediately.

Image Credit: NASA

It isn’t just pictures that are available immediately. When the Mars Science Laboratory landed on Mars in 2012, more than 1.2 million people watched NASA TV’s coverage live over the Internet. For February’s announcement of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets, more than a million people watched the press conference, and there were more than 500,000 social media mentions from outside NASA. We’re expecting similar numbers, if not more, for the Aug. 21 solar eclipse.

Social media has become the new communications frontier for NASA. When the Mars Phoenix lander arrived at the Red Planet, JPL’s public affairs team took to Twitter and started posting updates in the voice of the spacecraft. "We created the account, known as Mars Phoenix, last May with the goal of providing the public with near real-time updates on the mission," Veronica McGregor, manager of the JPL news office and originator of the updates, said in 2009. "The response was incredible. Very quickly it became a way not only to deliver news of the mission, but to interact with the public and respond to their questions about space exploration."

The excitement of space exploration is now available more quickly to more people more directly than it ever has been, and that trend seems only like to accelerate. For the solar eclipse, NASA will deploy television cameras, scientists and communicators across the United States, allowing anyone around the world to participate. For an agency with the mission to make the results of its missions known “to the widest extent practicable” – as required by the law that created NASA -- these are very exciting times. Who knows? Maybe one day we can make the Internet stand still again.