If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

On Episode 148, Felix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphael, co-founders and creative directors of Felix & Paul Studios and the International Space Station Experience Virtual Reality film, go into the details of how they are working alongside NASA to create a 360-degree, virtual experience with immersive views of space station life and research. This episode was recorded on February 20, 2020.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 148, “Space Station in 360 VR.” I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight. We’re coming up on 20 years of continuous human presence on the International Space Station, an orbiting platform that has provided countless insights into living and working in space. It’s brought us more of an understanding about the universe, about the effects of gravity, and about the benefits that research can bring to all of humankind. The International Space Station has taught us what humans are truly capable of and inspired so many more to pursue great things. And how people are inspired has come in many different forms. I’m sure a lot of us can name a movie or a book that inspired our love of spaceflight. Those who were lucky enough to grow up during the Apollo program may have been inspired watching history unfold live. Many remember watching or rather feeling their first launch and were inspired to take part in it. I get a chance to talk to astronauts a lot on this podcast. Sometimes they’re flown astronauts, and I always get a sense of their perspective from space. What is it like? How are they feeling when they look down on Earth? They talk about pictures and how it really doesn’t do justice to the true experience. But that might change soon. Part of NASA’s charter is to educate and inform audiences about space station life and research. A new initiative called the ISS Experience brought a specially engineered virtual reality camera onboard the International Space Station to transport audiences inside the laboratory. I’ve seen a small clip of it. It’s wild, like you’re actually in the space station. And you have a better sense of the scale of things and where things are way more than just looking at photos. So, coming on the podcast today is Felix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphael, co-founders and creative directors of Felix & Paul Studios and the ISS Experience VR film. They discuss the journey of making this film from designing the camera and operating on space station to working with TIME magazine, astronauts, and NASA, and what it takes to put it all together. So, here we go, the International Space Station in Virtual Reality with Felix and Paul. Enjoy.

[ Music]

Host: Felix and Paul, thanks for coming on the podcast today.

Felix Lajeunesse: Thank you.

Paul Raphael: Thanks for having us.

Host: Alright, this is a very interesting topic for this ISS Experience, a brand-new way of showing the International Space Station. Even just before this, I got a chance to look at the VR clip that you guys have put together. It’s like you’re there. So, I’m excited to see how this came about, starting with a little bit of background about you guys. Felix, we’ll start with you. What’s your background? And how did you get into the world of VR?

Felix Lajeunesse: So, I’m a director. So, I come from a traditional directing background. So, I directed documentaries and fiction, commercials, and music videos. I eventually met with Paul, and we started doing work together, co directing commercials and films, and we realized that we wanted to gradually move away from traditional practice of cinema and explore immersive installations, immersive cinematic installation, so we started to implement in our work holography and 3D stereoscopy cinema and projection mapping and live actors inside of the cinematic installations that we were creating, trying to move away from the paradigm of the screen and enter into the world of full immersion. And that was a process that we were on that was sort of a journey that we were on for a couple of years. And that eventually led us to virtual reality. So, it’s been a real kind of transgression from traditional cinema to fully immersive cinematic virtual reality.

Host: So, Paul, what attracted you about the, this immersive experience versus what you had historically done, just working with stuff that you would see on a typical screen?

Paul Raphael: I think it was, I mean, I’ve always been interested by what technology, how technology can enable new forms of storytelling, new forms of art, for one thing. The other really was about, you know, whenever I experienced something, it was a very different thing than being told a story. And you can, you can certainly feel emotions, and being told a story is an experience in and of itself. And I mean that as much as an oral telling of a story or a film or anything that is more showing you something rather than putting you in it. But being a part of an experience kind of opens up certain valves in your head that are, you just can’t, you just can’t open those in any other way. And I think that’s one of the things that really drew me in, and I think Felix as well, into the immersive realm. It’s, OK, well, we can make people feel things that they’ve never felt before by making the stories we tell immersive. And that’s been, you know, a big, a big reason in why we’ve been exploring this for the past few years.

Felix Lajeunesse: It’s like in real life, we are used at the concept of presence, right? We are present in real life, and so we feel the world through our consciousness, we feel it through our senses and through the impression that we have that we exist in this world. Right? And so, we are very sensitive to physical reality as human beings. And when you watch a film, generally you switch to spectator mode. You know? So, you shut down a lot of those valves that Paul talked about, and you enter in a mode of receiving something. You’re no longer in this kind of interaction with the world. You’re no longer feeling the world around you. You’re watching something that’s separated from you. It’s like —

Host: It’s almost passive, like you’re just, you’re just kind of, it’s a one-way communication. You’re not, you’re not, you don’t want to explore, you don’t want to look around.

Felix Lajeunesse: Exactly.

Host: Yeah.

Felix Lajeunesse: There is, there is that. And you can tell extraordinary stories through that. You know? Passivity is not necessarily a bad thing. But it’s something, we wanted to kind of explore beyond that and try to see, can we recreate through a media experience something that feels like the experience of the physical world? Can we sort of trigger inside of audiences the same kind of response and sensitivity and awareness and all of the things that make reality, the experience of reality what it is, can we actually replicate that inside of a media experience? And that was sort of the quest that we were on. That’s what led us to, you know, virtual reality. And it’s a quest that continues today, because virtual reality is not a finite medium. It’s an evolving technology. And so, we continue our exploration to push that further and further.

Paul Raphael: And, you know, I’d also say that, you know, virtual and augmented reality, or any form of immersive medium, really feels like what all mediums have tried to be, you know, but they just couldn’t be that before. You know? We started with cave paintings and oral stories and eventually, you know, photography and film and all sorts of I mean, certain, obviously I’m not saying it is the best medium and trumps everything else. But certainly, you know, when you think about our experience as humans, like as Felix said, it isn’t full immersion, it is volumetric, it is in all directions. Every other form of storytelling is an abstracted form, you know, for us. And that’s really interesting in and of itself, that there’s things you can do through abstraction that you can’t do through, you know, something that looks, that is more life-like in its representation. But it feels like after, you know, hundreds, if not, you know, thousands or millions of years, we finally have a way to tell stories in a way that really emulates reality. And then you can also take that beyond reality. But at least the baseline is a lot less alien than watching a flat rectangular image, or, you know, that is really a very alien thing. We’re so used to it, and it seems like the normal thing, and that VR is this exotic thing.

Host: Yeah.

Paul Raphael: But to me, it’s more like we’ve kind of come full circle and can finally use, you know, a medium that more corresponds to the way we experience reality.

Host: So, experience reality. You’re trying to tell a story through this immersive filmmaking, the way that you’re telling the story, and the way that you have to approach this has to be different than traditional filmmaking. What are some of those differences?

Felix Lajeunesse: Yeah, well, if you try to tell a story traditionally through virtual reality, what might happen is you might hinder the sense of presence and the sense of immersion. If you care more about the story construction and the efficiency of the storytelling from an, in terms of pacing, you know, compared to what you could watch on television, for example, compared to what you could watch on mainstream cinema, if you start to apply those principles, then what will happen is you will not nurture at all this sense of immersion and this sense of presence for audiences. And it will not make the medium bloom into, you know, and the experience bloom and become what it should be. So, it’s kind of a balancing act between trying to create sufficient space in sufficient time in each of the shots for audiences to truly find their footing, feel immersed, connect to the protagonists, or the characters, connect to the environment, discover, you know, their own place inside of that environment. So, that is a process of immersion, and it requires time, and it requires a certain set of spatial configurations. Let’s call it this way. And then the storytelling, very often what we do is we try to do it in a very kind of soft way. So, sometimes we will rely on voiceover narrations to kind of transport the viewer into the story without disrupting its immersion into the moment. Do you see what I mean? And we will try to, you know, navigate very slowly from one scene to another scene. And so, it’s a form of quiet storytelling in a way where you are definitely telling a story, but you’re doing it not in a loud way that prevents the viewer from feeling that state of immersion.

Host: Yeah, it’s different from the traditional storytelling where you’re trying to, you have a rigid storyline and you want people to follow that, and there’s a sense of focus. But it sounds like this is more of like a gentle guide through, through an immersive experience.

Felix Lajeunesse: You could say that, yes. And, you know, and if you watch a project like “Space Explorers” that we did, you know, no one explains that there’s not a story. There is a story. You are following the journey of these astronauts. It’s very compelling. But the way we’re doing it, it’s not by, you know, sort of taking the hand of the viewer and telling them how to think and telling them how to experience each moment and where they should look and how they should feel. We’re not directive with them. We’re giving them a lot of space to actually process what they’re watching and feel, complement what they’re watching with their own thoughts, with their own imagination, with their own sensitivity. And that’s, that’s how it works in the real world. You know? And that’s how human interactions work. So, we’re kind of trying to replicate that, bring some of that in our experiences, in our, and they’re a still narrative, you know, they still tell a story, but they just do it in a way that is more subtle.

Host: So, this is obviously something that’s you’re very passionate about, you’re very interested in telling stories this way, so you both created Felix & Paul Studios. Tell me about the genesis of that, how that came about.

Paul Raphael: Well, it really started when we tried the first Oculus prototype. I mean, we’ve been, we had already been exploring the immersive storytelling, as Felix mentioned. In fact, what we were doing around that time was very similar to virtual reality, even though it wasn’t with a headset. We were using 3D projection, you know, the same thing you do in a 3D movie, but we were using it in more of an installation format where we controlled all the variables of the viewing setup. So, the size of the screen, the distance from which the viewer was watching the screen, you know, it was a sweet spot, these were installations more than films. And really, they were kind of like narrow field of view VR, because you can look behind you, although I suppose we could have surrounded the viewer with screens and created something even closer to virtual reality. But this is what we were really exploring. And then dropped the Oculus Kickstarter. And the day we tried that, and if it wasn’t the day, it was within a matter of days, it became clear to us that if we could find a way to adapt the technology we had developed for our installations into, for the virtual reality format, this would probably be a complete game changer, not just for ourselves, but for, for storytelling in general. It’s worth mentioning that when the Oculus, when Oculus, you know, was selling the idea of virtual reality, their focus was really at the time on video games. And I don’t think they were narrow, that narrow minded that they thought that that’s all virtual reality was going to be for. But at the time, that was kind of their initial target. They’re like, you know, gamers are the most likely people to buy this at this point. And then, you know, probably people on the periphery, training, and, you know, all sorts of industrial applications, education, things like that. But, you know, we took this, this developer’s kit, we adapted the technology we had developed, and little by little within a matter of months, we got to, you know, a first demo of a virtual reality, a filmed virtual reality experience. And we started showing it around, and people were just completely blown away, as we were when we did it, and we were just incredibly excited. We started showing it everywhere. And eventually to Oculus themselves. And they had never seen anything like it. And that kind of triggered a very tight partnership with them, and really the genesis of the studio as we were able to build our team up, raise some funding, further advance the technology, and the technology is, you know, it was, it was hardware, it was software, it was process, post production process. And, of course, creative development of a brand-new language, which is telling stories in full, in virtual reality.

Felix Lajeunesse: Yeah, and maybe to add that we didn’t come, it was not the start of an exploration, it was an exploration that had started many years before that, prior to that. So, we had been doing a couple of years of immersive cinematic installations, as we mentioned earlier, and so when we created our first virtual reality experience, we approached it with a set of hypothesis from a creative standpoint as to what we wanted to achieve, what we wanted to investigate.

Host: Because it’s so new.

Felix Lajeunesse: Because it’s so new. And the one thing that we felt this medium would be extraordinary for is a sense, creating a sense of human connection, to just be with someone who is there at the real scale in a space with you, tricking your mind into actually thinking that that person is not beyond a screen, that person is sharing a space with you, and how that will make you react as an audience, how that will trigger something inside of you that’s very visceral, that’s very profound, you know? And the first experience that we ever created was just a one on one with a musician. So, he is sitting behind his piano, and he’s not performing, he’s just writing music, and so it’s a real scene. It was unscripted. We came in the studio. We placed the camera as if the camera was a friend visiting the artist. So, we placed it at a comfortable intimate distance from him, not too invasive, not too far, where a friend would sit. You know? And then we just filmed what happened. And we preserved these six minutes. We kept a continuous six-minute shot. And it’s just him goofing around, playing piano. He smokes a cigarette. He takes the phone at some point. He talks to his wife. And it’s just a moment in his life. But six minutes of this is not enough. You’re in it with him, and you’re feeling this, it’s so real, he’s so there, you’re so there, like there’s something going on in that moment that is really powerful, and, from a human standpoint. And so that was kind of the foundation, the first exploration that we did in virtual reality, and it worked out really well. And that was before we started asking the question of how we will articulate a narrative. It was just about getting to the fundamentals of what this medium can provide in terms of an emotional experience.

Host: Yeah, you saw, you saw the power that, of immersing yourself in just a moment, but you realize that to really, that that wasn’t enough time maybe to immerse. So, to fully tell the story, we’re talking about a longer period of time for you to really get into it.

Felix Lajeunesse: Yeah. And so, it’s like building block. It’s like any new medium that you want to play with, it’s like a building block. You will learn something and something else and you will start, you know, constructing something more complex with time.

Host: So, tell me about when the idea of telling a story about space, your interest in space, tell me when that started coming along.

Felix Lajeunesse: So, I think that it’s one of those things that from the get go when we started to play with virtual reality and became more and more enthralled with the medium and the possibilities of the medium, one of the early conversations we had was we need to do this in space. We need to actually recreate our sort of leverage, this immersive power of the medium, to transport audiences in the environment of space and make them feel that. And this is something that we wanted to experience personally. But we thought that this medium would be just a perfect marriage with space exploration. It feels, to us, and it felt to us at the beginning that space is something that you want to experience. You can talk about, you know, the journey of space exploration. You can say a lot of things about that. But you will always feel as a viewer, that it’s happening in another reality in a way. And so if we can sort of bridge that gap and bring audiences at the heart of this journey and make them feel like they are a part of it and make them feel like they can really, you know, not just look around, but feel like they are an astronaut to a certain extent, you know, and have more of a physical connection with that world, we felt that that was something we had to do as a studio and as artists from the get go. It took us a couple of years to get there. But we set out that goal from the very, very beginning of Felix & Paul Studios.

Host: Yeah. Well, tell me about that journey, where you said this is something that we have to do, this is a story we absolutely have to tell, and then eventually getting to the point where you’re starting to tell these stories with the “Space Explorers” series?

Felix Lajeunesse: So, one thing led to another in this journey. So, after we created the first experience that we talked about, which was called “Strangers,” which was this intimate one on one experience with a musician called Patrick Watson, we then met with Steven Spielberg’s team in Hollywood, and Colin Trevorrow, the director of “Jurassic World,” told us, “hey, I love this experience. So, what you did with Patrick Watson, this musician, can you do inside of the world of Jurassic World with a dinosaur,” which was an extraordinary brief, and so we did that, so we created that piece, we did a project with Fox Searchlight, with Reese Witherspoon and Laura Dern, which was our first fiction piece. And we also explored interactivity inside of that piece, gaze triggered interactivity. Depending on where you look, certain events will happen or not in the unfolding of the story. So, all of these early experiences were very short. They were below four minutes. But we were exploring different ways to articulate a story within immersion. And eventually we started collaborating with “Cirque du Soleil.” So, we created an adaptation in virtual reality of some of their shows. So, we’re not talking about film an existing show. We’re talking about restaging the show completely for virtual reality, for a one-person audience, and trying to scale a big spectacle down to an experience that will feel very intimate, that will make you feel like you’re one of the protagonists of this piece. And that eventually led us to work with President Obama. So, we got contacted by the White House because they were interested in outreach and finding new ways to communicate with younger audiences, and they were interested in that medium. So, we created two projects with the Obama administration. One was a tour of Yosemite National Park for the National Park Centennial, and the second project that we did was a virtual reality tour of the White House, guided and narrated by Barack and Michelle Obama. So, we did this. We also did a project with President Clinton. And so, you know, one thing leads you to another. And the project started to grow in duration. So, they were very short at the beginning. Very often, it was just one shot when we started. One project was one shot of three minutes, or six minutes, eventually started to get more and more elaborate and complex. And so, the format that we landed with was about 20 minutes, more or less, for our productions. And eventually we felt that we had all of the learnings, and from a creative standpoint and from a technology standpoint, to go out and approach NASA and say, “hey, we now want to tell the story of space exploration through virtual reality. Here’s what we’ve done, you know, and here’s what we want to do next.” So, we approached NASA initially with that desire to do this when we felt ready to do this.

Host: Wow, that’s quite a journey with a lot of very recognizable names, for sure. So, moving on from there, you approach NASA, you say, I want to do this. Now, I’m sure from there, it was quite a process to just get your foot in the door. And now we’re having the challenge of telling a story about space. Now, I know some of the story that you tell through the “Space Explorer” series is something here on the ground. So, that’s a little bit more tangible. But I know that your goal was to send a virtual reality, a 360-degree camera to space.

Felix Lajeunesse: Yeah, I mean, so, the first thing we did when we started to, you know, visit JSC and meet different NASA executives and different people that we had to basically convince that this was worth everybody’s time, was showing them the work that we had done already. And just that spoke in itself expressed a lot. And you could, you could extrapolate from that and think about, you know, how will space exploration translate through this medium? It was kind of relatively easy to make that, that projection, that translation from the work that existed that we had done to what we wanted to create. And then something that happened that was very important is that we started to meet with astronauts, and they became excited, and they wanted to be a part of it. And so, and that was a game changer. That was when things started to really accelerate, and we found real momentum within NASA to go out and do these filmings and do these recordings. And then one thing leads to another. When we started to process the shots, even before the final product, we started to show it to some folks, and people got very excited about what we were doing. And then when we finished Episode 1 of “Space Explorers,” which was launched at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018, then we came back here, and we showed it to everybody. And so, we went from department to department to show the 20-minute episode. And then we really started to build, I think, support for the medium and the pertinence of using this, this medium to tell the story about space exploration. And then more astronauts saw it and more NASA executives saw it. And eventually we became people that were no longer, you know, the newcomers with the new medium, but we were, you know, part of the family to a certain extent.

Host: Integrated. Wonderful.

Felix Lajeunesse: Integrated, yeah.

Host: So, you know, this is, part of the family you want to tell these stories, what are you trying to tell with “Space Explorers?” What was, what was the immersive experience for those that may have not heard of the series?

Felix Lajeunesse: Well, I think that, you know, “Space Explorers” is humanity’s journey. It’s a journey that’s about everybody. And it might sound like a cliché to say this, but it is true. All the discoveries that we’re making in space are ultimately about understanding who we are as a species, you know, better understanding the biosphere, better understanding our place in the universe and where we’re headed. And I think that that’s a very profound and important quest. And it’s really about everyone on this planet. And so, we felt that, you know, only just a few people get to go to space, a few hundred people have visited space. But we felt that their journey truly matters, and that it’s important to broaden the access to that journey to as large an audience as possible through that medium. And so we’ve been interested from the get go to the full story arc of the astronaut’s journey, from how they train here on Earth, you know, how they get to learn the fundamentals of what it is to be an astronaut, how they learn to fly, and then their missions on the ISS, how they adapt to the environment of space station, how do they do all of the science, the work, how do they experience the overview effect, how do they live the human collaboration of being with astronauts from all those different national space programs all around the world? How do they prepare for a spacewalk? And then documenting the spacewalk and the post EVA. And so and sharing with them thoughts and regards to the future of human spaceflight and the next step. So, every step of the way, it’s a very exciting journey, but it’s a journey that I think everybody can feel involved into, because ultimately the purpose of that journey is about everybody. So, it’s a story that we feel has a real universal appeal.

Paul Raphael: You know, something that I think of it like we’re at this incredibly rare moment where humanity is almost in a state of metamorphosis. Right? Like if you think back at when, you know, there were no ground-based creatures, and everyone lived underwater, and then at some point some creatures made it out there, and, you know, there was no way to record that. In fact, the only recording of that is DNA and fossils and biology. And that’s the record of that.

Host: Yeah.

Paul Raphael: And now we’re making our first steps, even though it started over 50 years ago, there is kind of an acceleration right now in humans becoming, you know, extraterrestrials, you know, basically it’s almost inevitable, unless we destroy ourselves before we get there, that humans become interplanet, an interplanetary species. So, that seems to me like one of the most important and fascinating things you could possibly document today. And to get a glimpse as an earthling of what it is to take those first steps off of the planet, I mean, how amazing is that, you know?

Host: Yeah. And, you know, just from the clip I’ve seen of the just in space, the one with David Saint-Jacques was the one I’m thinking about right now. But he just looks so comfortable in that environment. And you talk about a metamorphosis. It’s, you know, you’re transported to this moment, but it’s like, you can see there is an established life there that he’s very comfortable. And to be a part of that is, that’s an experience in and of itself. I want to talk about how we got to that point, how we got the camera up to space, what it took to make that happen, to tell this story, to get people to immerse in this particular location has its own difficulties. So, what were those challenges? And how did that happen?

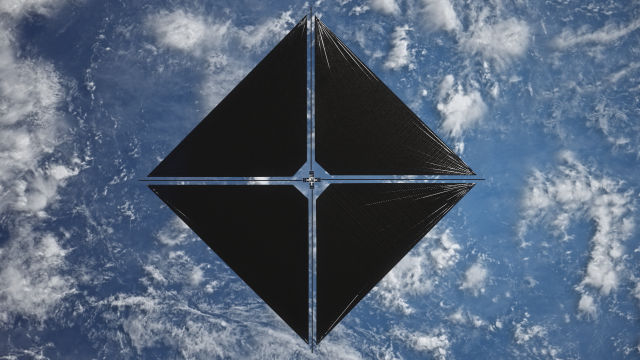

Paul Raphael: Well, you know, we built the first VR camera now six or seven years ago. And since then, we’ve been iterating on that design, and we’ve built four, we’re at the fourth generation of our land-based camera, and we’ve built countless variations and special purpose cameras for shooting in different situations here on Earth, or underwater, or in the air. For this particular project, we kind of had to take a step back and look at not sending one of our own cameras, because they’re so custom designed, and they’re not [Federal Communications Commission] FCC-certified, and all, you know, at the time that we had to get a camera up there and with all the requirements, we decided let’s look at all the cameras that are out there, let’s pick the one we think best suits what we’re trying to do, and let’s, knowing what we know about virtual reality cameras, both on the hardware, software, processing and playback, how do we make that camera do things it could never do before, right? So, we started with a preexisting camera. In this case, it’s a Z CAM V1 Pro. And we, first of all, modified it to, for to, adhere to the specifications of being sent to the International Space Station. And we modified it and upgraded it in ways that allowed it to do things it couldn’t do before. And, yeah, that’s basically how we, how we got there.

Host: What are some of those specifications and modifications that made it a space worthy camera?

Paul Raphael: So, one of the things that was always very important for us, just the virtual reality in general, is proximity. Right? And that’s the hardest thing to do with a VR camera, because you’re essentially, when you’re shooting in VR, you’re trying to do two things that are fundamentally incompatible. You’re trying to shoot in 360 degrees without any distortion, which is usually done shooting with a nodal rig. You could put a single camera on a nodal rig, spin it around with, you know, from a single point, and then you stitch all this together. And the closer you are to the lens’s nodal point, which is basically where all the rays of light converge, the less distortion you have when you get, when you take all these different pictures and put them back together. On the other hand, when you’re shooting a VR, you want stereoscopy, you want 3D images, you want to be able to see a different image from each eye. So, you need to shoot two different images that are approximately 65 millimeters apart. So, between one requirement being all the images need to be shot from a single point that’s as small as possible, or the other requirement being they all have to be 6.5 millimeters apart, this is, this is kind of, you know, it’s impossible.

Host: Yeah, yeah.

Paul Raphael: Unless you do, unless you find the right way to bend light, so to speak, it’s just a fundamentally incompatible equation. So, our cameras have always been designed with that, you know, how do you, how do you best cheat that with, you know, with the express intention of being able to shoot objects that are closest? Why objects that are closest? Well, VR is a medium of intimacy and presence. You know, the closer something is, without being too close, the more you can feel that thing or that person’s presence. Most cameras that are designed are designed as general-purpose cameras, and they want to make them as easy to use as possible. And, you know, for as many people to just grab and go. So, they’re actually, you know, they’re not optimized for any specific thing. Whereas our cameras have always been really focused on proximity. But if you can get proximity, you can also get distance. Right?

Host: Yeah.

Paul Raphael: So, one of the things we had to do, starting with the Z CAM, is kind of make up for the fact that it isn’t expressly designed to shoot things in close proximity. When we’re shooting in a space that is extremely small, I mean, there is no angle in the ISS that isn’t in proximity. And not only that, we wouldn’t be up there to have complete control, and even if we were, we wouldn’t always have the freedom to put the camera anywhere we want, you know, we have all sorts of restrictions on where and how a camera can be placed for any given shot. And so, we knew we would probably end up with things that would be way closer to the camera than we would even do with our own cameras here on Earth to, you know, to facilitate post production and to keep things comfortable. Right? So, we had to, you know, find ways to make up for, for that. And one of the ways we do that is we created a motorized base for the camera to rotate and kind of capture a, what we would call a slit-scan of a scene. So, what, you know, even though the Z CAM has eight lateral cameras and one to get the top or the Zenit, by spinning the camera, we get the equivalent of an infinite amount of cameras. For a still frame, right? And that gives us kind of a baseline, a calibration of the actual geometry of a space. And then we only have to deal, we only have to make sure that the astronauts don’t get too close to the camera, because then we know how the good, you know, kind of a perfect image everywhere else. Right? So, that’s just one of the ways that we do that. The other way is, you know, even though we’re shooting with a camera that isn’t, wasn’t designed at the studio from scratch, we did adapt our customized software and pipeline that we did build from scratch for that camera. So, all the benefits from the software and post production side are now applied to this camera as well. So, these are just a couple examples on how we took an external camera and kind of made it our own.

Host: A couple examples, but that was, that’s a tremendous amount of work. It really is. I mean, this is, you’re designing this camera for a very, very specific need. And I’m sure, you know, you’re talking about requirements for the filming requirements too. But there’s also the fact that it’s going to space. There’s also the fact that this thing has to launch on a vehicle with intense vibrations. So, designing a camera like that has a significant amount of challenges. And I’m sure you put a ton of work and a ton of thought and a lot of intricate design into this camera. But eventually you’ve got to package it up and you’ve got to put it on a launch vehicle and you’ve got to see this thing go up into space. Did you see it launch into space? Did you see the camera? Were you there for it?

Paul Raphael: Absolutely. Well, we were watching, you know, we were watching the live broadcasts.

Host: OK.

Paul Raphael: You know, along with hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people, but it was definitely an amazing emotional moment. We did pop some champagne that day.

Host: Well deserved. There’s a lot of work that went into that.

Paul Raphael: Absolutely.

Host: Yeah. Alright, so, tell me about what it takes to actually, you talked about the intricate design that it takes to think about ahead of time what goes into this camera. Tell me about actually filming, the operations, what is it like to work with the astronauts, to work with the footage? That has to be a tremendous amount of footage that you’re, that you’re getting. And not only a tremendous amount, but just like it’s coming in, yes, large I guess quantities, but the files themselves have to be enormous. So, working with all of that on a day to day basis, maybe not day to day, but very often with the astronauts.

Paul Raphael: Mhmm. So, this is a three-part question.

Host: A lot of questions, yeah, yeah, yeah. I guess what it takes to work, I guess if you’re filming on a day, take me through, take me through a day where you want to film with the astronauts and it’s time to set up a camera and start that work, what’s that like?

Felix Lajeunesse: Yeah, so generally what we do is we identify ahead of time what we’re going to film. So, whether it’s an interview, what we call an astronaut log, or whether it’s science that we’re going to film, or some operations, satellite launch, or something else, so we know ahead of time, sometimes two weeks, three weeks ahead of time what’s going to happen. And then in which module it’s going to happen. And then more or less where inside of that module it’s going to happen. And so, from there, we sort of run a topology study. We imagine or envision where the camera could be based on preexisting studies that we have made before. And sometimes we make adjustments to that. And we say, no, we want it in that access or in that orientation. And then we produce documents that are submitted to NASA. And then eventually it gets approved. And then on the day, it turns into documents of operation that the astronauts can actually read on the day and say, oh, OK, well, this is where they want a camera. Great, OK. Oh, it’s in the way of this. What about if I put it there? And so, there’s always some adjustments. But that’s the general flow of operation. It is done with some pre-planning. There are other types of shots that we call crew autonomy, where we’re basically deferring to the crew to decide where the camera will go, especially when we’re capturing certain scenes that are more private, for a certain extent, where they will be doing like some interactions between each other, like a crew meal, for example, or something like that. So, they will sometimes place the camera on their own. So, it’s a, it’s one approach or the other. But generally, I would say that things are very well planned ahead of time. And, yeah, and on the day of the operation, our team is there to support everything that is happening. And so, we can validate the camera placement, make sure that technically everything is fine. We’re working with NanoRacks to do that. So, they are like our sort of intermediary. And then once everything is ready, then we start to roll. And then, you know, we are waiting a couple of weeks after that to see the final result, because everything is shipped to us through the form of low-resolution proxy files. So, think of it as an unfolded sphere in a way, just like when you open those books as a child and see an unfolded world map. So, that’s kind of what we review as offline footage. And then we make selections. And we will send back to space station an [edit decision list] EDL time code to basically say, OK, we would request high resolution files for that time code, that time code, that time code. And then we will download that. So, it’s a process that helps us not asking for too much bandwidth from space to ground. And so that’s, that’s the kind of workflow.

Host: OK, yeah, you’re basically scanning for what you want, and then they send that’s where the massive amount of data comes through, because you’re just, you’re trying to pick your moment. Because you know, it sounds like everything is thought about ahead of time. So, you know about your shots a few weeks in advance. But ultimately, you’re trying to package this into a story.

Felix Lajeunesse: Right.

Host: Right? You want to, you want to say something. You want people to experience something when they’re there. And what is that something for filming on the International Space Station? What is that something that you’re trying to tell?

Felix Lajeunesse: So, there are a few things. First of all, the story follows the dramatic arcs of the astronauts. So, for example, we document our mission from the moment that they arrive on station, and then their process of adaptation to life in space. And then getting to be part of the family of astronauts. And then the work that they do on station, but also their perspective in regards to their work, and the meaning of what they do, their relation to planet Earth, the future of human spaceflight. And so, and eventually the departure back to Earth. So, these are the dramatic arcs that we follow with multiple astronauts over the course of a year. And then through those dramatic arcs in that sort of, let’s call it the network of characters, right, we are exploring different themes through that. So, we want to learn about the adaptation of life in space of the astronauts. We want to know more about all the different science investigations that are happening on station. We want to know how it’s like to run a space station, which is this giant flying machine. So, what it takes to actually run this. We want to understand better the relationship to planet Earth, you know, the overview effect and all that. And so, there are different ways to explore that question. But we are making space for that in our story. We want to better understand the nature of the international collaboration and the way it plays out out there in space. And ultimately, we want to also really document everything around the spacewalks, from the way they get sort of prepared, all the steps of preparation that lead to spacewalk, and then taking the viewer outside and following the astronauts during a full spacewalk from egress to ingress, which is something that we will film later this year.

Host: Oh, that’s exciting.

Felix Lajeunesse: So, it’s a combination of those story arcs that we’re following and those themes that we’re exploring basically.

Host: Wow. Now, you know, we talked about all the work that it really took to get to that point where you’re filming and you’re thinking about these stories and it’s a story you want to tell. Tell me about when, you know, you were first hooking up that camera and you got those first 360 images, 360 video from space looking at that. How – what were you thinking that you were expecting? And then what, you know, how did it actually turn out to be?

Felix Lajeunesse: Man, we were excited. It was very phenomenal. The first filming day that we did was with David Saint-Jacques in January 2019. Everything about that moment felt extremely stressful. It was the first time that we were testing the whole production pipeline.

Host: Yeah.

Felix Lajeunesse: The first time that we saw an astronaut manipulating the camera, putting it in place, starting the recording, all of that, every step of that felt extraordinarily precious. And then downloading the data, getting the data in the cam, being able to review it, all of that was like a miracle in a way. And once we processed the data and watched it in virtual reality, we were blown away, just like the audience that watches this for the first time. We were there. Even though we had been working for a long time to prepare this, we had never had that experience of being on the space station through virtual reality and experiencing microgravity and having an interaction in a way with a human being that is in front of you, but that is floating and that is changing orientation as they talk to you, and this shock of being with someone in the microgravity environment through virtual reality. You feel it, you know? Maybe not as strongly as you would feel if you were there with your real buddy, you know, but you still feel it. And so, we got all of those emotions. We got all of those, you know, it was a completely new phenomenon for us as well. And so, it was a very emotional beginning of production, I would say.

Host: Yeah. Now, you know, you’re working with this footage to put it together. You’re looking at it. Tell me, tell me what it’s like to actually work with the footage, for those that might not know about what it takes to put a VR experience together. The, you know, the stitching and the editing and working with the files and processing, rendering, that sort of thing. And then from there what we can ultimately expect in terms of a finished product and where to go get it.

Paul Raphael: Well, you know, this was the first time we were working with a camera that wasn’t our own fundamentally.

Host: Sure.

Paul Raphael: So, there was that hurdle of, and that worry of, you know, all the, we had done tests on Earth. But, you know, as much as you want to test for the unpredictable, it’s kind of impossible to test for the unpredictable. And so, we were getting the footage and we were, you know, the cameras were always a little closer than we would have liked to a wall or cables were protruding and all over the place. And, you know, luckily, like what I mentioned earlier, the slit-scan technique that allowed us to get kind of a perfect geometry of the scene for at least everything that was static, combined with, you know, adapting our tools to be able to work with footage that was not as optimal, at least geometrically, as we were used to. It all worked out. It took a bit of adaptation. And at some point, we kind of got a little worried at how much time it would take us to process the footage, both in terms of the manual labor and the automated processes, because the data was much higher, it was much high resolution than we had worked with in the past, which is, that’s a great side effect, but came with, came with its downsides. You know, ultimately, though, the results that are coming out are very similar to what we’re used to getting, which is incredible, because we’re in such an uncontrollable environment that’s so remote and that comes with so many restrictions and hoops, you know, that you kind of have to jump through to get anything, you know, and I’m not saying that as a criticism on anything, but it’s just the reality of such a sensitive environment. You know? But, yeah, we’re, we’re, it’s all working —

Host: A lot of work, but, but it’s, and it has its challenges, but it’s coming together. So, what can we expect? Where, what’s the finished product, and where is it going to be available? How will it be distributed?

Felix Lajeunesse: So, we’re producing actually many different outputs out of this. So, on one hand, we are creating a cinematic virtual reality, four timed 25-minute episodes. And that’s going to launch on all virtual reality platforms across the world. We’re also producing a traditional 2D 16 by 9 version of this. So, we’re looking at a 60-minute television format. Because we’re filming at such a high resolution that it actually allows us in post-production to animate a camera. And the final result looks like you had a very skilled cameraman, you know, in space, filming the astronauts, and never missing anything. And so —

Paul Raphael: You’re basically animating a camera with as much control as you would have in a Pixar film, or, you know, a CG film where you can totally animate the camera with perfect control, which is better than any astronaut could do if they had like the best cinema camera in the world with them.

Host: Yeah, because then you’re trusting the camera operator that you’re trusting.

Paul Raphael: Yeah, and they don’t have time. I mean, instead of one astronaut setting up his camera and then doing what he’s got to do, he or she’s got to do, they just put the camera down. And we are, we can direct, we can do the cinematography in post, and eventually in real time, but that’s for later in the conversation. And it’s, it’s kind of amazing. It’s like we weren’t even expecting that when we first started this project. And we kind of stumbled onto that realization and were like, wow, we not only have the most immersive footage ever shot in space. We may have some of the most trippy and immersive two-dimensional footage, and that’s where this started becoming a project that we’re now in discussions with some of the major networks and streamers about distributing to a much wider audience. And I think somehow many of the qualities of the full VR experience get, get ported over through this Zero-G cinematography that can only be enabled from a 360-degree image.

Felix Lajeunesse: And then so that is for the at home distribution. And then out of home, we are also producing a version of the ISS Experience for domes and planetariums. So, for large scale events where you can bring thousands of people to have a communal experience projected inside of those very large circular spherical screens. And we’re also creating a large-scale traveling exhibition in partnership with TIME and a company in Canada called Phi Centre. And that large-scale traveling exhibition is going to tour the world and it’s going to feature the virtual reality content that we have captured in space.

Host: Wow. Yeah, so, this is going to hit every, every channel you can think of. That’s incredible.

Paul Raphael: You won’t be able to avoid it.

Host: That’s the hope, right? Alright, so tell me about, let’s end with your, with your ambitions. You know, you talked about what’s coming up is filming a spacewalk. That’s very exciting. And I know you have even ambitions beyond that to tell the story about space exploration.

Felix Lajeunesse: Yeah, I mean, we want to make virtual reality the default way to document space exploration moving forward. We think that everything that was created so far demonstrate that it’s a perfect medium to be part of this journey. And we want to continue to document the advancements and the next steps in human spaceflight through virtual reality. So, we’re looking forward to the upcoming missions. The Moon mission obviously is an important next step for mankind. And then Mars and beyond. And we want to be a part of this every step of the way.

Host: Wow. Yeah. And you can, you already talked about the value from even the 2D perspective, being able to just mount a camera and leave it there, but not miss a moment.

Paul Raphael: Exactly.

Host: And have that and have that freedom to kind of look wherever you want.

Paul Raphael: Yeah, I mean, if that’s, if that’s a useful thing to have on the ISS, just imagine on the Moon, you know, where you can literally just plant a camera, a VR camera on a tripod. Not only are you putting humanity on the Moon, but you can now film any shot without any input from the astronauts. You could get multiple shots from a single point perspective. You could get both a shot and a reverse shot at the same time. You can animate the camera remotely in real time. I mean, it’s kind of a super camera. You know? And we’re thinking, you know, yes, they’re definitely going to have normal cameras —

Host: Sure.

Paul Raphael: –up there. But we think that putting a camera, a VR camera up there wouldn’t just be a bonus. I think it could be a fundamentally upgraded experience on many, many levels.

Host: See, what I’ve really enjoyed talking to both of you today is really just the whole breadth of what this project is. It’s a, it’s a completely different way of telling a story. It’s immersing. It’s this way of getting people to experience what it’s like to be on the International Space Station. But, and, again, I’ve seen, I’ve seen this myself. I’ve put on the goggles and I’ve looked around. And I’ve even had a chance to look at astronauts put it on and take it off and be like, “yeah, that’s it, that’s the space station, that’s what it looks like.” And so, it’s something that you can’t, you can’t replicate otherwise. So, appreciate what you guys are doing. But also, the technology demonstration and the applicability of working and creating a camera that’s specifically for that, and what may be used and applicable for future missions to the Moon and Mars. Absolutely incredible. Appreciate what you both do. And thank you for coming on the podcast today. Really appreciate it.

Felix Lajeunesse: Thanks for having us.

Paul Raphael: Thank you.

[ Music ]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. Really fascinating conversation we had with Felix and Paul today about everything that’s really gone into working on this film, the “ISS Experience.” Make sure you keep up to date and look for that experience, and then maybe even invest in some virtual reality goggles so you can do the experience its full justice. You can find updates on NASA.gov/ISS on that and the many other experiments and initiatives going onboard the International Space Station. If you like podcasts, there’s a lot of episodes of Houston We Have a Podcast you can listen to in no particular order. Go to NASA.gov/podcasts to find those and the other podcasts we have across the agency and any topic you’re interested in. You can follow us on social media. We post on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea to the show. Just make sure to mention it’s for Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on February 20th, 2020. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Norah Moran, Belinda Pulido, Jennifer Hernandez, Kelly Humphries, and Gordon Andrews. Thanks again to Felix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphael for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us how we did. We’ll be back next week.