Name: David Content

Title: Payload Project Manager, Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST)

Formal Job Classification: Physicist

Organization: Code 448, WFIRST Project, Flight Projects Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

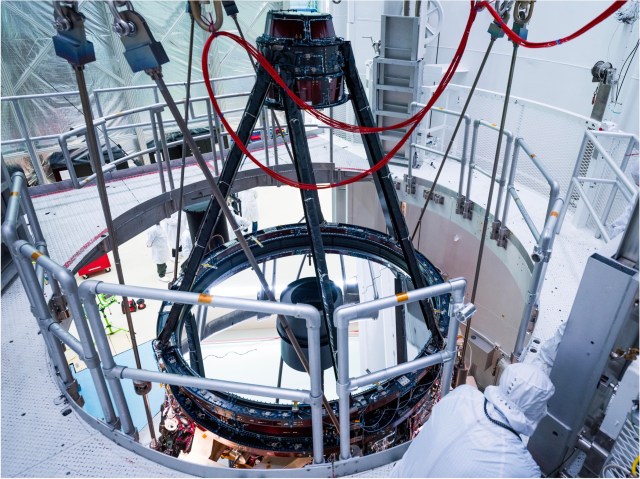

I manage the payload for the next large astrophysics telescope, the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), which is scheduled to launch in the mid-2020s. The payload includes the telescope, two instruments and the structure that holds them all together.

The telescope is 2.4 meters in diameter, or Hubble-sized, and includes a primary mirror and other components transferred from another government agency. The wide-field instrument will produce Hubble-quality pictures with 300 million pixels. The coronagraph will demonstrate technologies for imaging planets around nearby stars.

Why did you become a physicist?

I knew I had a mathematical brain very early. I am the third of five brothers, all spaced out two to four years apart. When my younger brother was 5, I asked my mother if she was pregnant. She said I would be some kind of math whiz when I grew up.

A pure mathematician is very theoretical, and I am more practical so I became a physicist. I got a physics degree from Hamilton College and then a master’s and doctorate in physics from Johns Hopkins.

How do you think a liberal arts background helped you at NASA?

Once you are at NASA, thinking, writing and communication skills are critical for a successful career. The liberal arts background gave me those skills. I minored in philosophy, which also taught me critical thinking. I also took public speaking. A liberal arts background made graduate school a little harder, but it made my work at NASA much easier. The people skills and understanding about non-science subjects have really made a huge difference for me at Goddard.

How did you come to Goddard?

My thesis advisor had NASA and other grants and told me about a job here. My job title is engineer, but my training is in physics.

What is your subject matter expertise?

Optics. My Ph.D. project was building a spectrometer to study fusion plasmas, so I had a background in optical instruments that gave me the job in Goddard’s optics branch which is one of the best in the world. I became an expert in diffraction gratings, which split light into colors. I also helped build several instruments including the Hubble Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS), which is still working on Hubble today.

After Hubble, I learned how to build space telescopes. I worked on several other projects including one for sounding rocket telescopes.

What have you worked on for WFIRST?

I started as the lead optics engineer and ended up making the first optical design for the 2.4 meter telescope. I then became a systems engineer for the payload. The project manager asked me to switch into project management and manage the whole payload which I have been doing for the past five years.

What makes WFIRST so exciting for you?

WFIRST is exciting because of both the fundamental science and the exceptional team.

In short, we are answering these questions: Are we alone? How did we get here?

The mission is going to measure the history of the expansion of the universe better than any other ground or space measuring instrument has done or is in planning currently. The coronagraph is going to demonstrate technology that will let us plan future missions to look for earth-like planets around nearby stars.

From the beginning, the project has had the benefit of excellent leadership from Jeff Kruk, the project scientist, and Mark Melton, the mission systems engineer. Project managers Kevin Grady and Jamie Dunn are among the best leaders at Goddard. Their dedication helped set up the project for success.

The project also involves working with the science team, which is composed of brilliant astronomers from all over the country and abroad. I get to interact with them which is both exciting and demanding.

I have met several Nobel Prize winners and some who might win them in the future. Knowing that you are working on the same project as them is very exciting. Eating dinner with them feels like a graduate seminar in astrophysics. I feel very fortunate to have this job.

What is the difference between working as an engineer and working as a project manager?

A project manager is also responsible for costs and schedule. Also, project managers are dealing with all the staffing and personality issues. As a prominent scientist once said, “At least half the problems we deal with in building large space missions are carbon-based.” So we often say, “Oh, I have a carbon-based meeting.”

Engineers can dive deep on the engineering. But project managers have to see the big picture. I have always been a big picture guy. To me, that is the point of physics. I always want to see how what I am doing fits in the big picture.

If you are not curious, you will never look for the big picture.

How do you handle carbon-based issues?

First, I talk one on one with the people. You never criticize people in front of others. I try to model the behavior I expect from others. I try to be direct with people and give them specific feedback when needed. Communication skills are essential. The soft skills of reading emotions through body language and the subtexts of what people say are crucial. This is an entirely different skill set from engineering.

What is a common management issue?

Getting busy people to meet deadlines can be challenging. Engineers often strive for the best, most perfect solution. As the saying goes, “Sometimes ‘better’ is the enemy of ‘good enough’.” These are judgment calls that you sometimes need to help people make.

How do you delegate?

I have a wonderful deputy, Roman Kilgore. Parts of the payload are located in Rochester, New York; at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California; and Boulder, Colorado. My deputy and I usually alternate trips, which number a few each month.

To delegate, you have to aware of the work and the skill sets of the people you have. You also need the self-confidence that you don’t need to do it all yourself. I have observed that a failure to delegate reflects a lack of self-confidence. At first, you may need to follow up to make sure everything is going smoothly. With good people, that quickly becomes unnecessary.

When you mentor, what advice do you give?

Not everyone is equally emotionally intelligent and it can sometimes show up in job performance. I tell them to follow through in what they commit to do, enable your team to succeed by organizing the work and communicating and delegating effectively, and listen to each other.

What do you do for fun?

About five years ago, I had quintuple bypass surgery. My doctor told me not to run any more marathons. I had only run one. I had to do something to stay fit, so I started hiking mountains. I have hiked the Appalachian Trail from West Virginia to southern Pennsylvania through a series of day hikes. I also bike to work occasionally.

Who is your favorite author?

I have been a science fiction buff since I was a kid. Most recently, I read a book by Robert Silverberg.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center