It was early morning – just after 7:30 – on April 23, 1966. A heavy mist clung to the ground. A voice was heard counting down – 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 … Ignition!

Suddenly, a loud sound – described by some as a “crack” – broke the morning silence. A bright blast of color overpowered the mist – an explosion of flame that lit up the early morning.

“We have fire in the bucket!” someone shouted.

The space age had arrived in a most unlikely place – the lowlands of southern Mississippi, near the banks of the meandering East Pearl River. And for a nation struggling to gain its footing in the modern technological world, it came just in time.

No one would have predicted such a development a few years earlier.

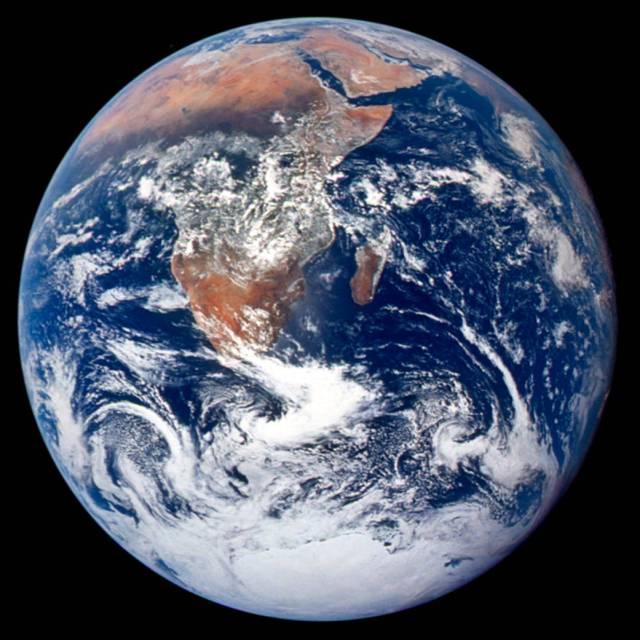

Russia’s launch of the world’s first artificial satellite into space signaled the start of a frenetic space race. Suddenly, travel beyond the gravitational pull of this planet was a possibility, not just fodder for Buck Rogers comic books.

American leaders responded by establishing the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1958. Three years later, President John F. Kennedy set forth an unimaginable dream for the nation – for humans to safely travel to the moon and back by the end of the decade.

The race to the moon had begun.

There was a lot of groundwork to be done, including the selection of various sites to implement a space program. By early fall of 1961, NASA officials had chosen three of the four needed locations – a launch site in Cape Canaveral, Fla., a manufacturing site near New Orleans and a spaceflight laboratory site in Houston.

All that remained was the selection of a site for testing the new powerful rocket engines that would be needed to propel astronauts some 238,000 miles to the surface of the moon.

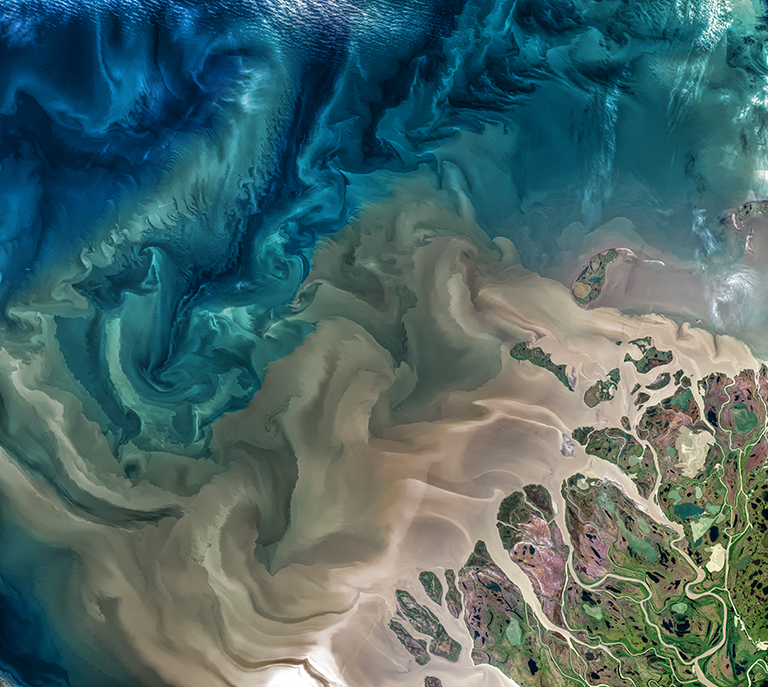

There were several criteria to consider, such as proximity to river navigation and isolation from populated areas. It came down to six sites – all of which were visited by a committee of decision makers. NASA officials settled on a relatively unknown area in western Hancock County, Miss., not far inland from the Gulf of Mexico – an area not so far removed from its swampy, uninhabited natural state.

In the past, the area had been populated by Indians, pirates and soldiers. At the time of the site selection, there were a few small sawmill towns had occupied the area. However, by the 1960s, the lumber industry had declined – and the towns of Santa Rosa, Westonia, Napoleon, Gainesville and Logtown were suffering. Now, the government needed this land for a new purpose, a national purpose. For a year, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers negotiated with residents and land owners, relocating the area population.

By May 1963, 138,000 acres of land had been acquired. Of the total, 13,000 acres were deemed necessary for actual testing facilities. The rest of the surrounding acreage was a practical acquisition – to buffer the surrounding community from the noise and potential hazards of firing the huge rocket boosters.

Finally, as summer descended on the region in 1963, trees in the area were once again cut down, but this time for a new reason – to make room for the modern age.

The work began with difficulties and a tight schedule. In 1963, a record manifestation of mosquitoes plagued the first workers at the site. In 1964, torrential rains delayed progress. A new year dawned in 1965 amid concerns that the initial schedule could not be kept. Indeed, time was running out for America to reach its moon goal. Test stands still had to be completed for test firing the Saturn V rockets to be used in the Apollo program. Canals still had to be dug. Facilities still had to be built.

The work was comprehensive – leading to the creation of 9,000 new jobs with an annual generated income of $65 million for the surrounding communities. NASA officials poured personnel into the area and even sent famed rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun to the site to lead the charge toward completion.

Von Braun understood the critical nature of the work. “It will be at the S-II stand now under construction that (the Saturn V second-stage) will receive its only full-duration firing before a lunar mission,” he told workers in late 1964. “If our program slips one year, it would cost $1 billion. This kind of money is not available from Congress just for the asking.”

In other words, this was it. A delay would cost dearly and could mean the nation would lose the race to the moon, something no one wanted to contemplate.

The pace turned frantic. Soon, more than 6,100 persons were on site. Nearly one-fourth of them worked for General Electric in technical and base-support functions. North American Aviation and the Boeing Co. also were on site. Those three companies were the largest among 30 prime and 250 sub-prime contracting agencies working to meet the deadlines of 1965, even as NASA officials were upping the ante.

Mid-summer, they announced a truly ambitious goal – the first real test fire on Jan. 2, 1966.

Two months later, Hurricane Betsy roared ashore in the area, slamming the Gulf Coast region, killing 76 and gaining notoriety as “Billion Dollar Betsy,” the first $1 billion natural disaster in American history. Betsy did not damage the new test site but it wrecked work schedules as personnel and equipment ended up scattered throughout the area to escape the storm.

However, workers regrouped-and persevered. Crews worked desperately to complete the test stands, while engineers finished designing a canal-and-lock system that would enable them to barge the rocket engines from the Michoud Assembly Facility in nearby New Orleans, through the Intracoastal Waterway, across a stretch of the Gulf of Mexico, up the Pearl River and right to the foot of the test stand. To do so required deep canals and a lock system for raising the barges as much as 20 feet from the level of the Pearl River.

The workers and engineers did not meet the initial Jan. 2 test date. But it was just a few months later that success was achieved with the first test of a Saturn rocket stage on April 23, 1966.

Less than a year later, when a Saturn V first-stage booster was fired for the first time, the noise and blast from the most powerful rocket ever built in America shattered a bank window in the town of nearby Picayune. It also shattered any doubt that the site – then known as the Mississippi Test Facility – was prepared to fulfill its mission.

Overall, the Mississippi site was used to conduct a range of Saturn rocket tests. The hard work paid off on Oct. 11, 1968, when three astronauts on NASA’s Apollo 7 mission made the first manned orbital flight aboard a craft whose engines had been tested at the Mississippi site.

Eight months later, on July 20, 1969, Kennedy’s dream became a reality, as astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. Six more moon missions would be conducted before the Apollo program ended in the 1970s.

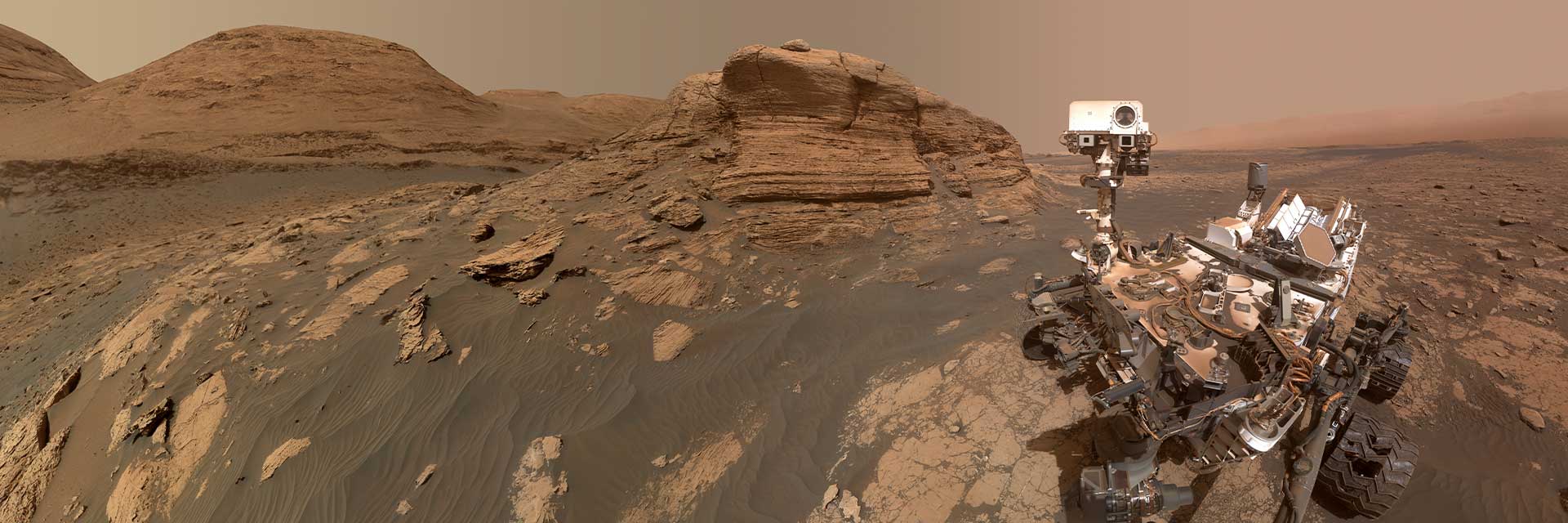

For the Mississippi Test Facility, that ushered in a time of change as its facilities were modified to test engines for NASA’s new launch vehicle, the space shuttle. Testing space shuttle main engines has remained the primary business of what is now Stennis Space Center. However, in 2004, President George W. Bush announced a new vision for NASA, which called for the space shuttle to be retired by 2010 and astronauts to return to the moon by 2020.

In 2006, one of the historic test stands at Stennis was modified again, to test the J-2X engine that will be used for the next stage of America’s space program designed to carry man back to the moon, with eventual journeys to Mars.

So now, 50 years after the national space program began, the section of Mississippi lowlands now known as Stennis Space Center has grown into the America’s largest rocket engine test facility. And 42 years after the first “fire in the bucket” was ignited, the site continues to fulfill its overriding mission of ushering in the future of space exploration.

For information about Stennis Space Center, visit: https://www.nasa.gov/centers/stennis/

Related Multimedia:

+https://www.nasa.gov/centers/stennis/news/releases/2008/CLT-08-042-cptn.html

– end –

text-only version of this release

Paul Foerman, NASA News Chief

NASA Public Affairs Office

Stennis Space Center, MS 39529-6000

(228) 688-1880

Paul.Foerman-1@nasa.gov