When you think about what astronauts do in space, you probably don’t picture them taking out the trash.

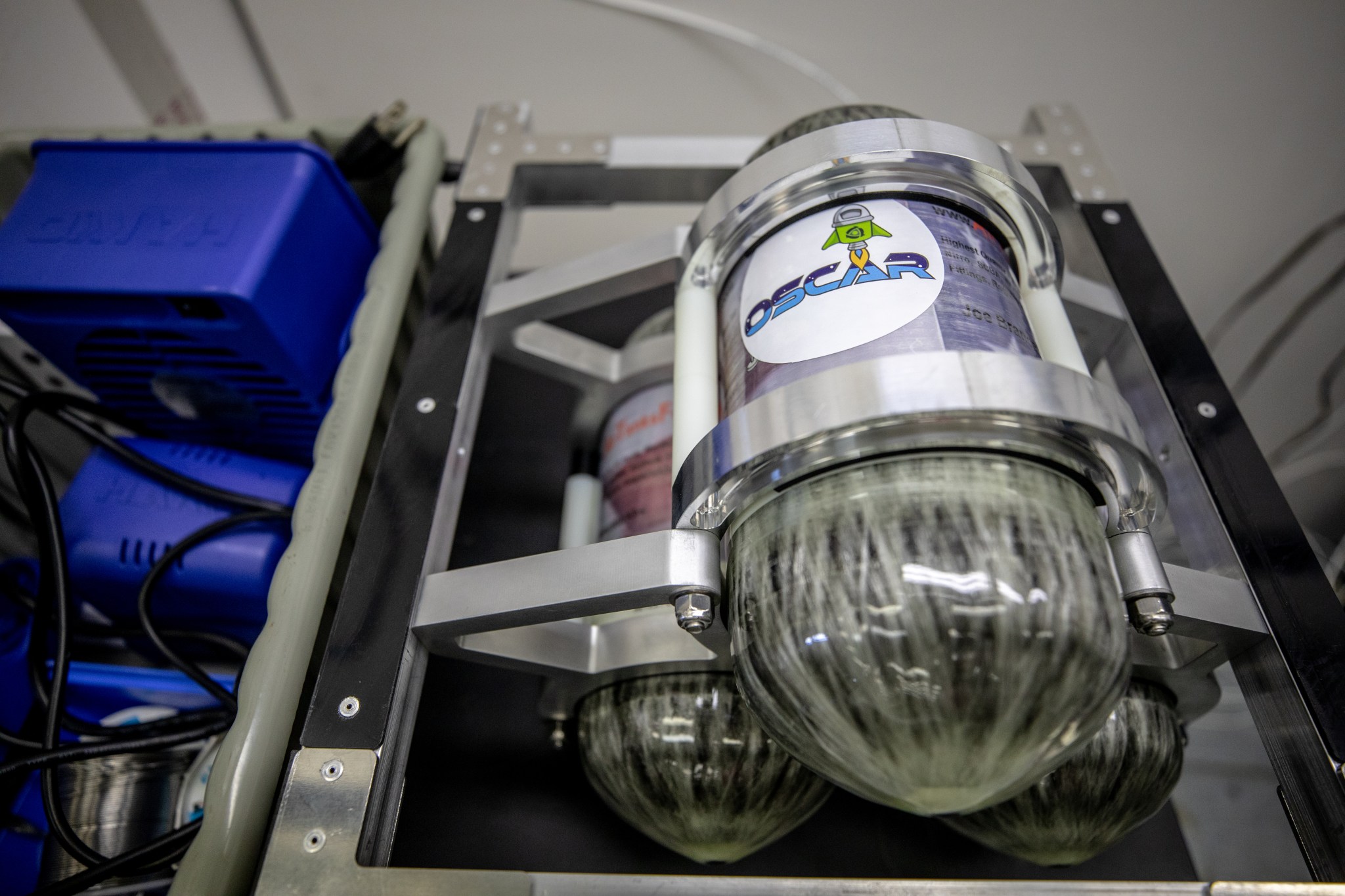

As NASA prepares to return astronauts to the Moon and then venture to Mars, a lot of planning goes into how to keep crews safe and healthy and enable them to do as much science as possible. One of the challenges is how to handle trash. The Orbital Syngas/Commodity Augmentation Reactor (OSCAR) project, is an avenue to evolve new and innovative technology for dealing with garbage in space.

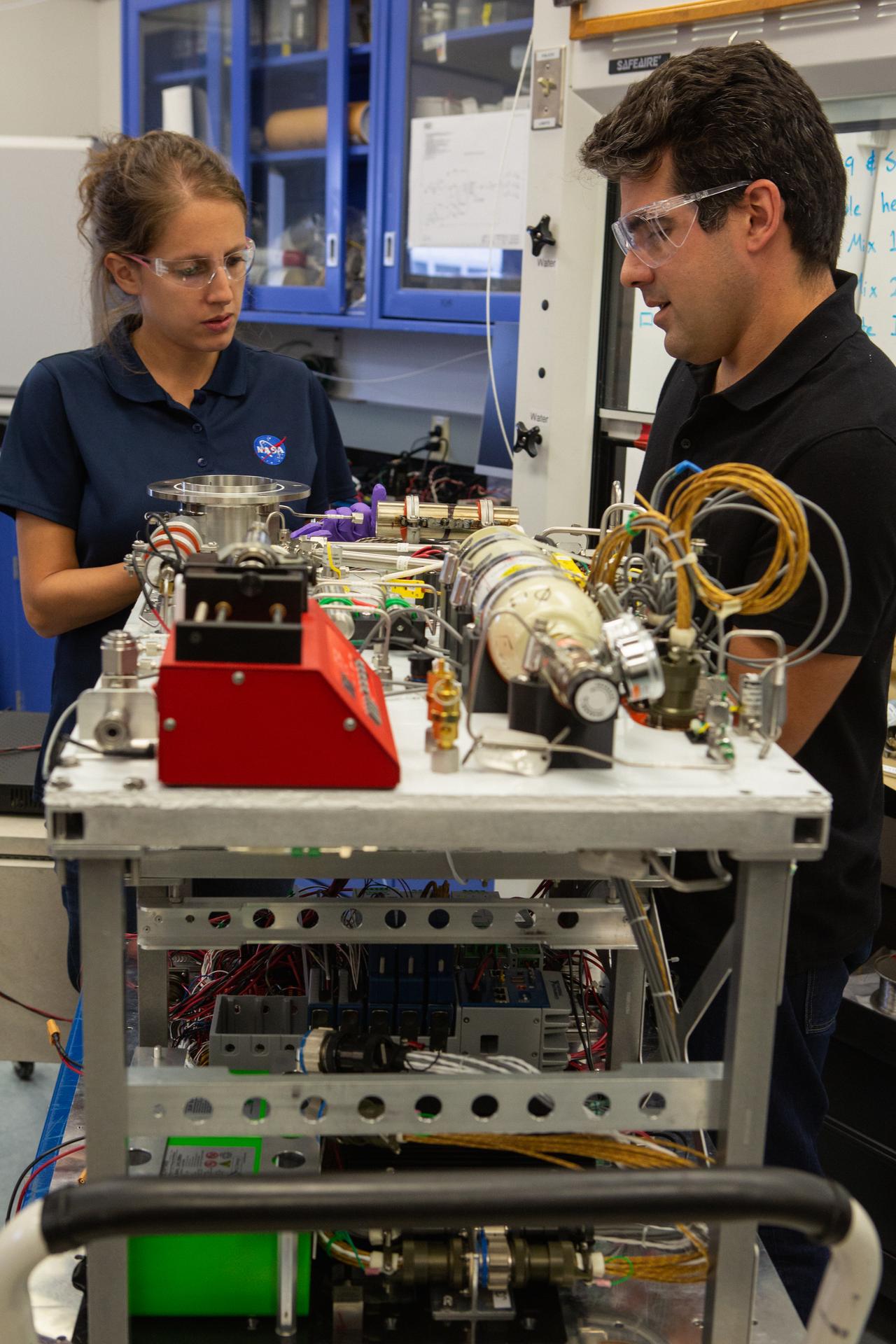

OSCAR is managed by principal investigator Annie Meier who leads a multi-disciplinary team of early career researchers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The recycling technology could boost deep space human exploration missions.

By processing small pieces of trash in a high-temperature reactor, OSCAR’s technologies could enable reuse of discarded materials on long duration, deep space missions. This would reduce overall mission mass, increase usable spacecraft and habitat volume, and improve mission reliability and robustness.

From idea to implementation

The OSCAR payload has some history, starting from a sketch on a napkin.

Several years ago, NASA funded a study of different trash conversion technologies. Building on this “trash to gas” concept led to further work funded by the Early Career Initiative within NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD) — an effort that provides technology development opportunities to the agency’s best and brightest early career employees. Through the initiative, the OSCAR project proposed to study how to convert trash and human waste into useful gases such as methane, hydrogen and carbon dioxide — a synthetic gas blend, or “syngas.”

“With the OSCAR project we took a step back and charted an incremental approach, to develop technology and space hardware that may eventually go where humans are,” said Meier.

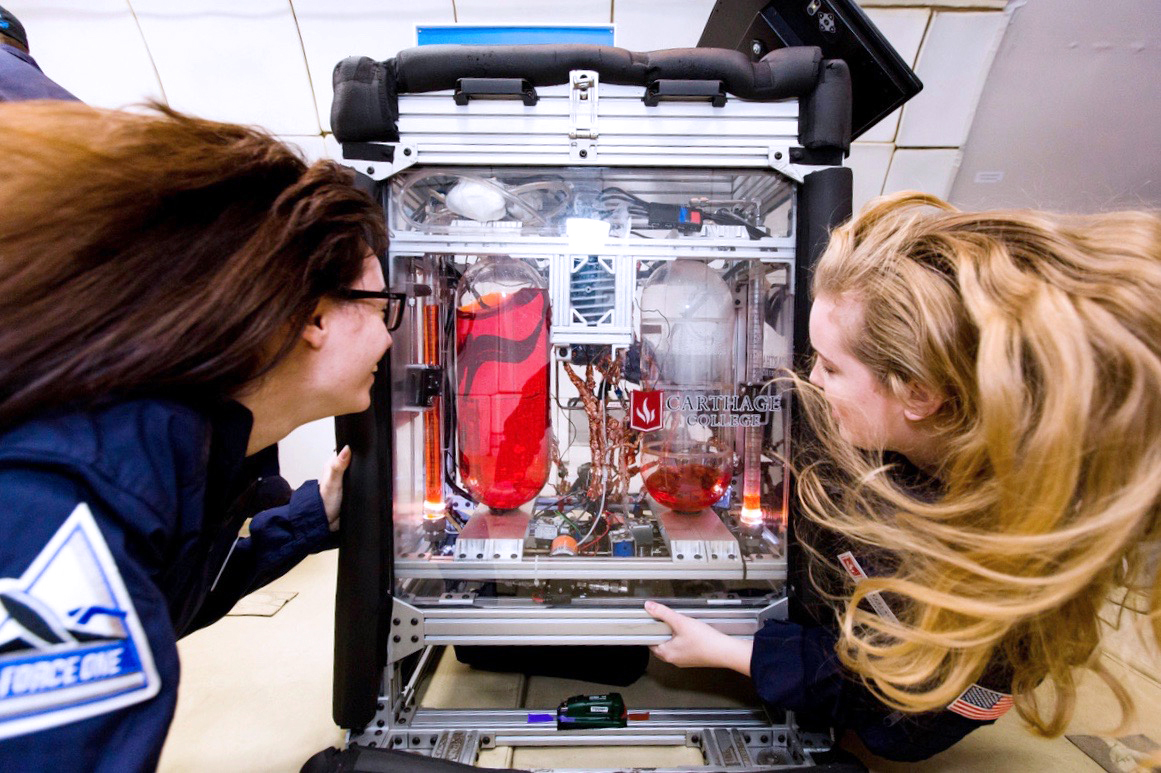

First, there were drop tower experiments at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, where the team tested an early OSCAR prototype for about two seconds in microgravity as it fell nearly 80 feet at Glenn’s 2.2 Second Drop Tower. Then, the team moved to a 5-second test at Glenn’s Zero Gravity Research Facility. OSCAR benefited from the drop tower appraisals, allowing the hardware to be optimized, with a better understanding of the gear’s combustion science. The project team even learned what types of trash the reactor handles best.

“Those early tests gave us confidence in the gravity versus microgravity design of OSCAR,” Meier said.

First microgravity flight

Years in the making, OSCAR’s recycling abilities got a taste of space.

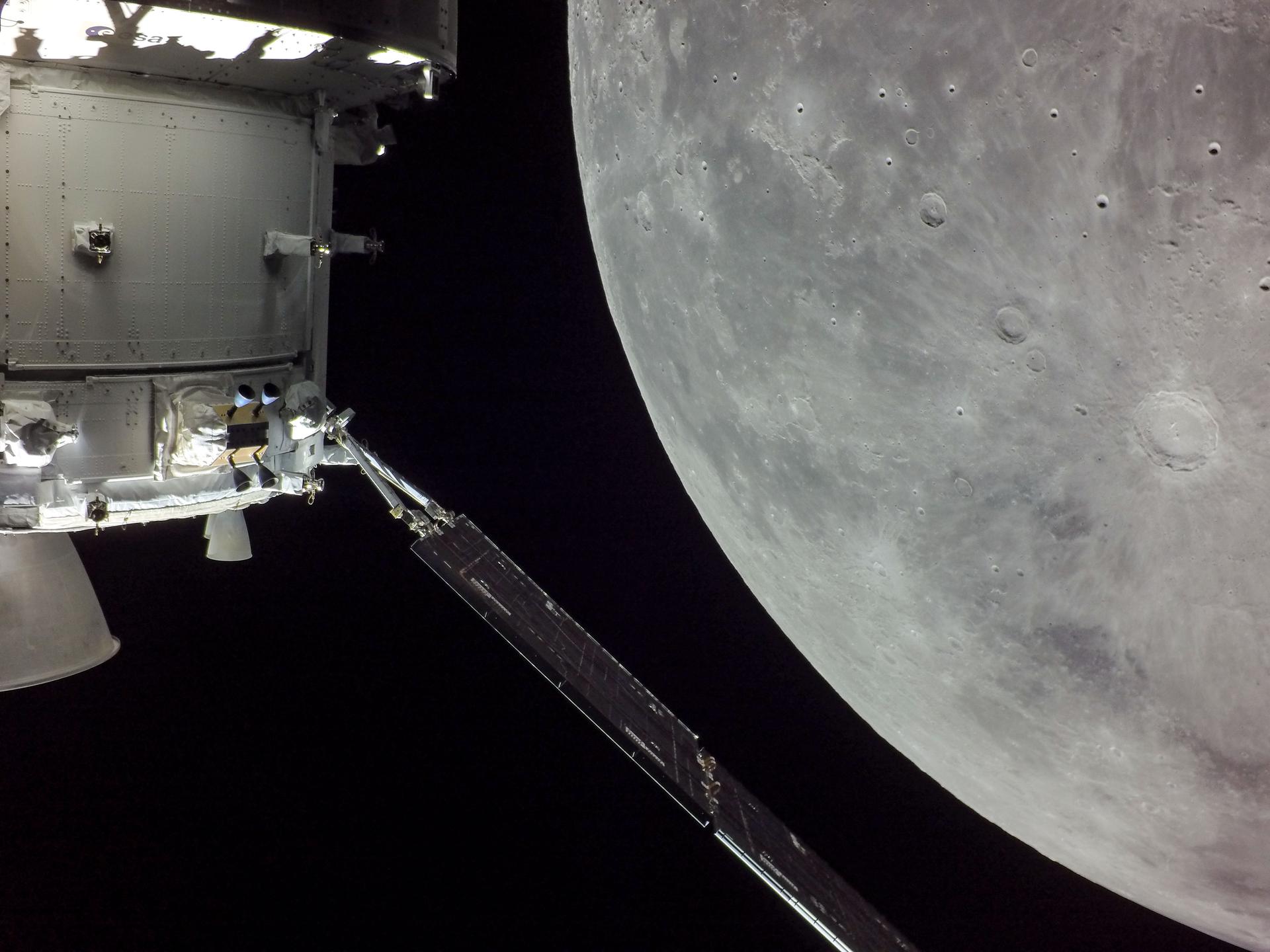

On Dec. 11, 2019, OSCAR was a payload on Blue Origin’s New Shepard suborbital rocket. It was the company’s first full-stack payload, meaning OSCAR was able to have the space it needed to do complex studies in microgravity flight.

During the suborbital flight test, backed by STMD and its Flight Opportunities program, the rocket lifted OSCAR and other payloads onboard more than 64 miles above Earth’s surface, where OSCAR experienced about three minutes of microgravity to show off its features.

“Because OSCAR was fully automated, there were moments of terror on takeoff, hoping it would work. It was able to run through all of the operations. Now, with all the data taken during flight in hand, this suborbital test was a real confidence builder,” Meier said.

Logistical waste

What type of trash is there to deal with in space?

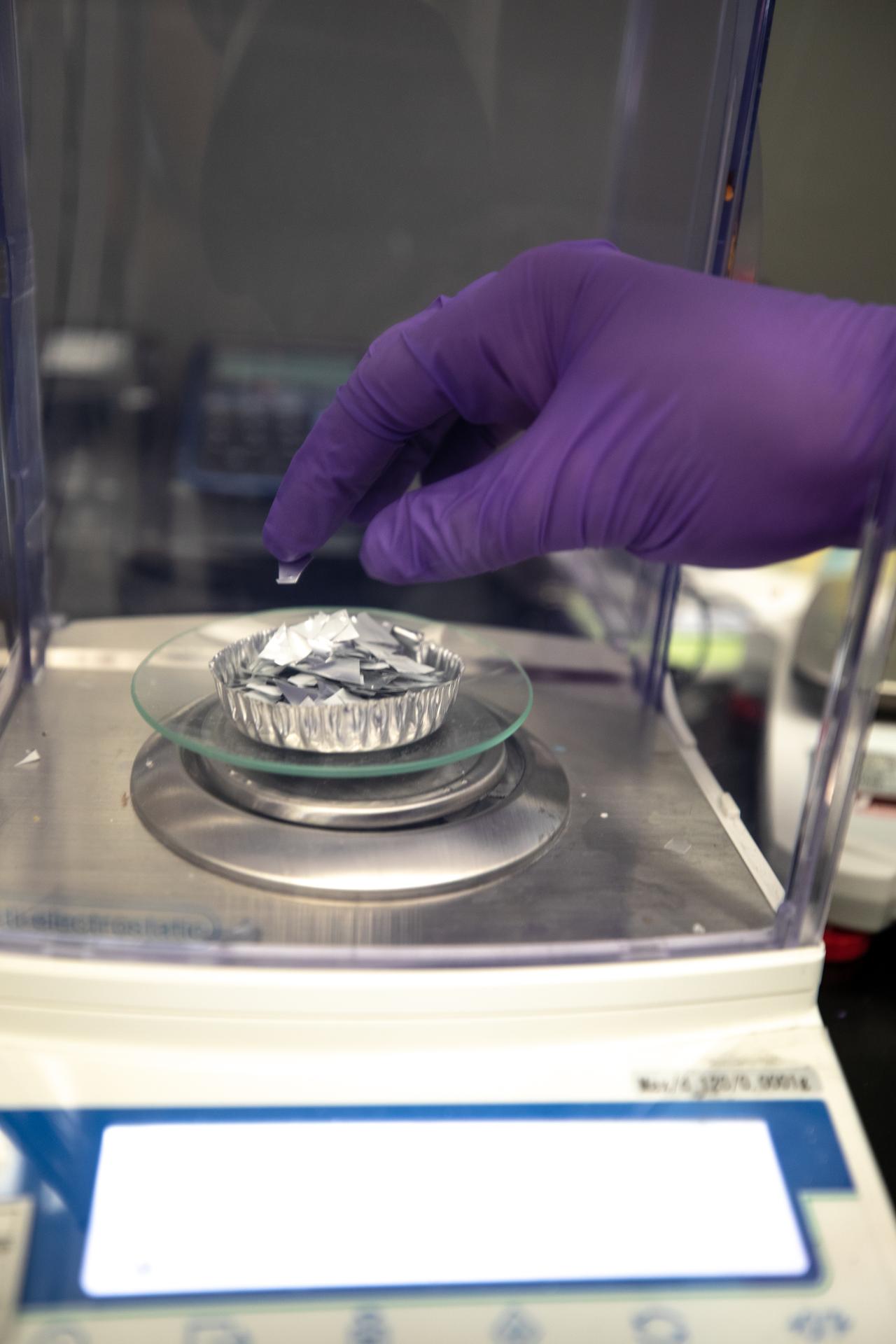

On a one-year mission, a four-person crew will produce over 5,700 pounds (2,600 kilograms) of waste. “We call it logistical waste,” Meier explained. It includes hygiene items like wipes, toothpaste and bristles on a toothbrush, food packing, and even clothing because astronauts don’t have a washing machine.

“We also have a recipe for fake poop,” Meier said. “It’s a mixed-waste simulant OSCAR can process.”

OSCAR would allow for safe trash disposal by venting repurposed waste in the form of an inert gas off of a spacecraft. OSCAR could also enable astronauts to recover useful materials from the trash including fuel, metals and water.

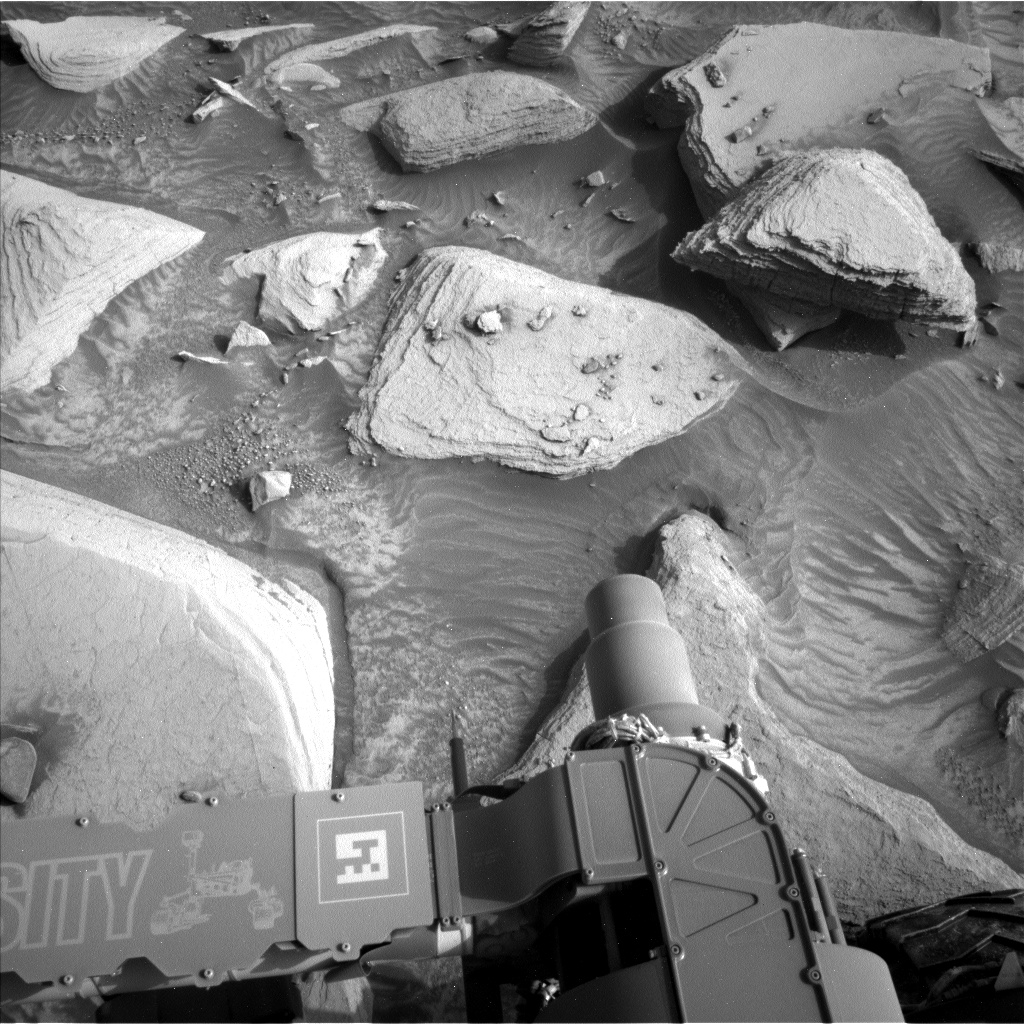

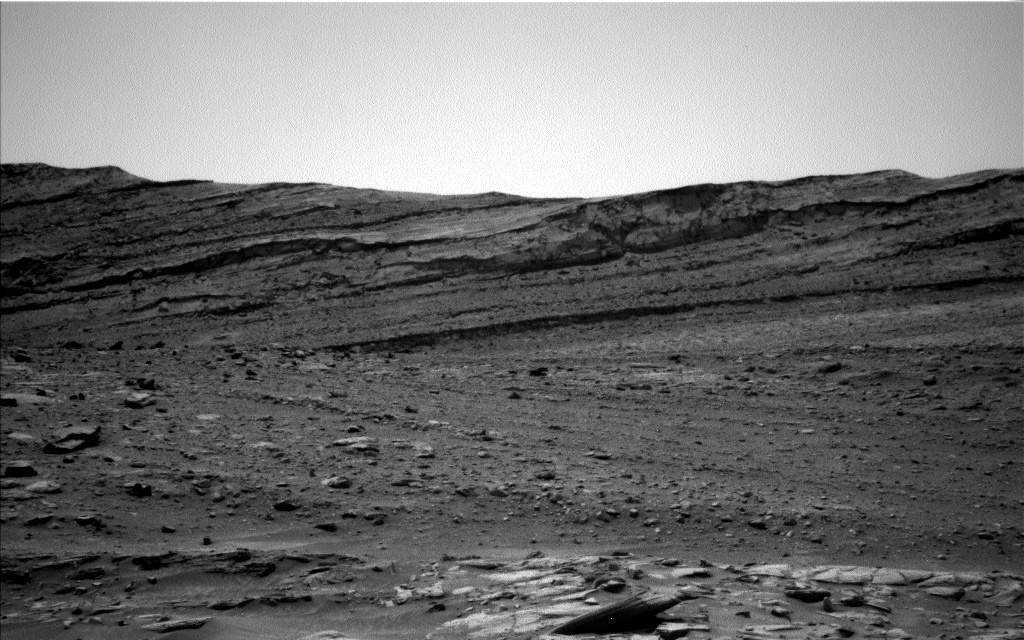

Deep space missions, from the Moon to Mars

At present, along with OSCAR, Meier is engaged in trade studies of other space trash handling technologies, comparing them in an “apples to apples” way to discern their relative strengths and limitations, be it weight or power consumption levels.

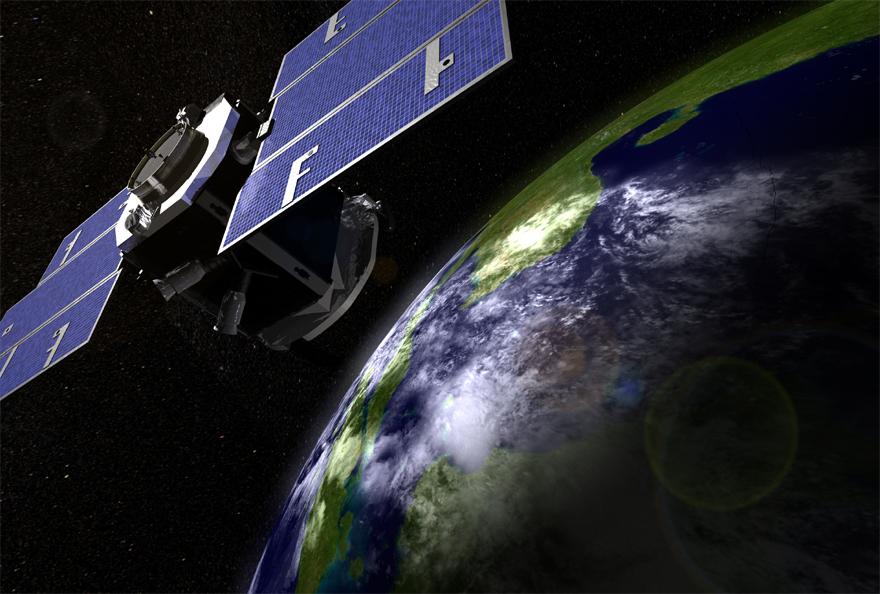

The intent of this work is to discuss demonstration hardware for locations like NASA’s Gateway – a small spaceship, part of NASA’s Artemis program, that will orbit the Moon and consist of living quarters for astronauts, a lab for science and research, and a port-of-call for visiting spacecraft.

“The sooner we can get this type of hardware demonstrated in a true long duration microgravity location, like Gateway, the sooner we can ready this technology for other deep space missions,” said Meier. “Demonstrating the hardware and learning how it operates in microgravity over a long period of time would be extremely useful when planning for crewed missions to Mars.”

Benefits on Earth

While working on the issue of trash in space, Meier believes the OSCAR project is useful here on Earth and could benefit isolated communities, hospitals or college food cafeterias. “Hopefully, the things that we learn can help improve waste energy technology and make it more efficient.”

Seeing OSCAR take to the skies aboard Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, Meier said, was an unforgettable experience.

“Being based in Florida, I am very fortunate to see rocket launches often. But I’ve never personally had such a huge part in one payload before. It was my first time ever for sending anything into space. It was fun, rewarding and an awesome opportunity,” Meier said. “Suborbital flights with our commercial partners are a great chance to test technologies and move them forward. Doing so can help so many researchers, so many scientists, to develop their technologies faster.”