5 min read

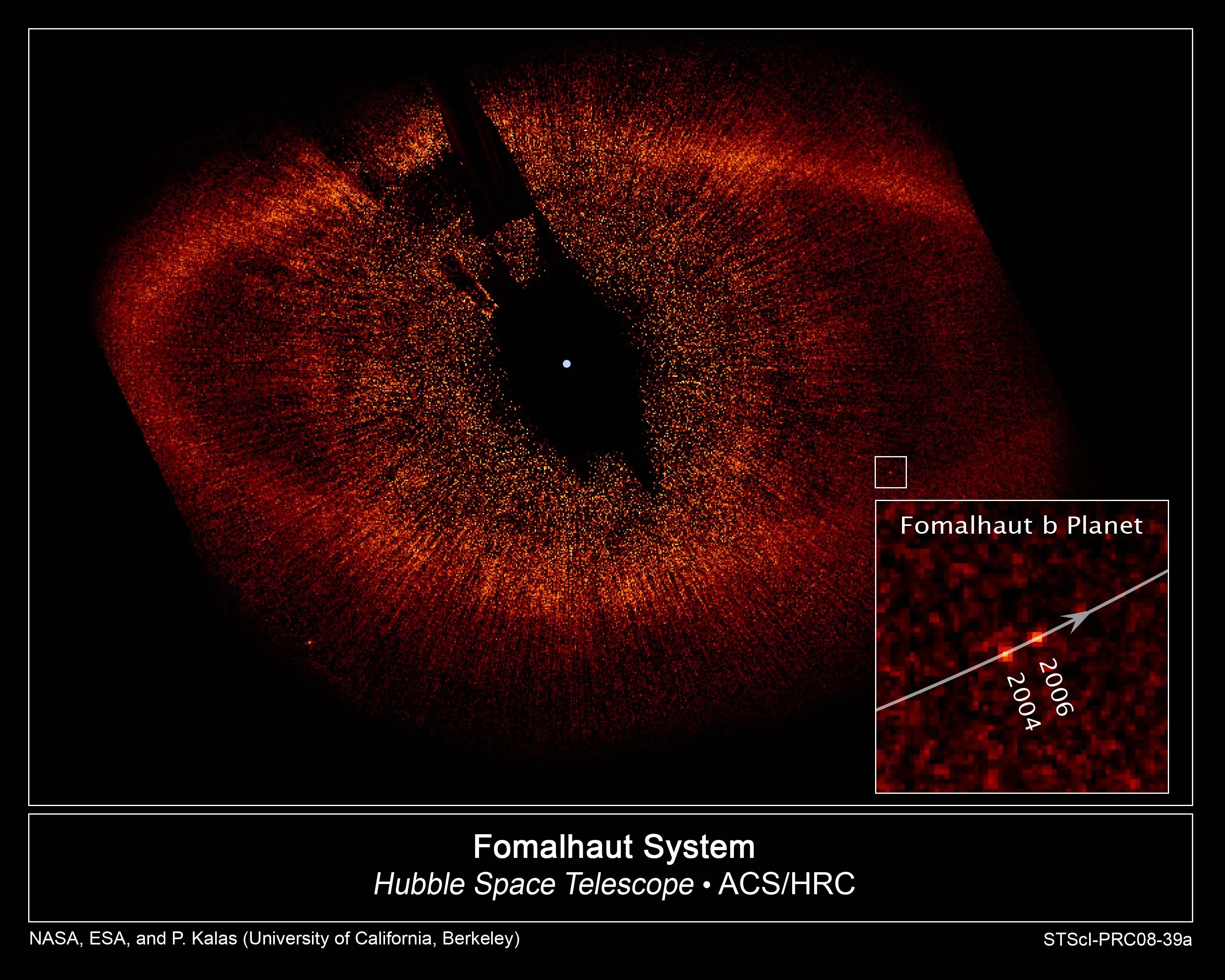

This visible-light image from the Hubble shows the newly discovered planet, Fomalhaut b, orbiting its parent star.

Credit:

NASA, ESA, P. Kalas, J. Graham, E. Chiang, and E. Kite (University of California, Berkeley), M. Clampin (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.), M. Fitzgerald (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, Calif.), and K. Stapelfeldt and J. Krist (NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.)

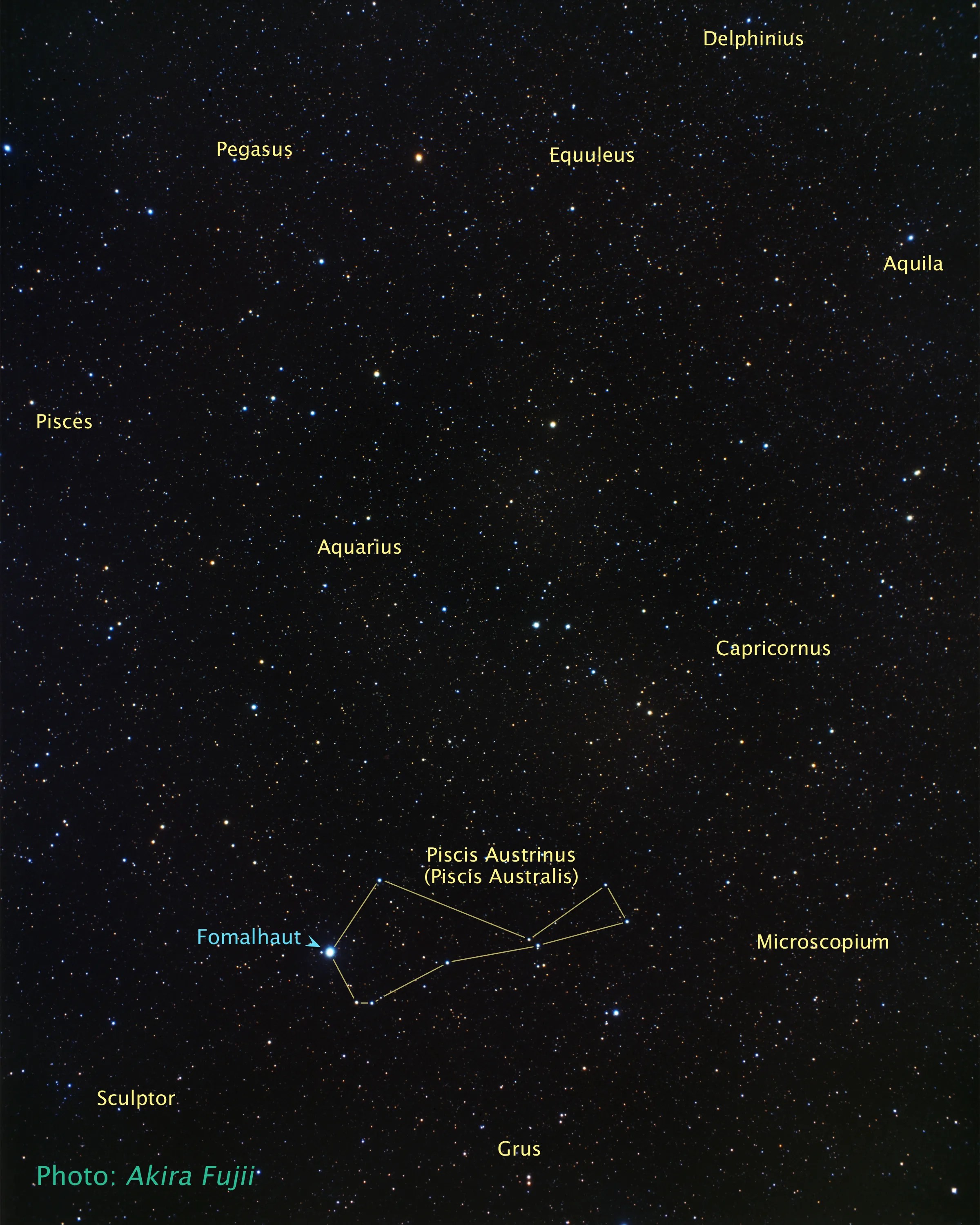

Ground-based image showing Fomalhaut's location.

Credit:

A. Fujii, NASA, ESA, and Z. Levay (STScI)

This animation simulates Fomalhaut b's path around its star. The red dot represents the planet, the white dot represents the star, and the brown ring represents the debris disk.

Credit:

NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI)

In 1846 German astronomer Johann Galle discovered Neptune when he peered through one of the Berlin Observatory’s telescopes. Galle spotted Neptune at almost exactly the same spot where scientists had predicted a new planet would be. The prediction was based on unexpected changes in Uranus’s orbit that scientists believed were due to the gravitational pull of an unseen object.

Over the past 13 years, present-day astronomers have found more than 300 planets orbiting other stars. But none of those worlds has been viewed directly. To detect most of those extrasolar planets, astronomers have measured slight wobbles in the parent stars caused by the tugs of unseen companions.

Astronomers cannot see the alien worlds because they are too far away and too dim -- about one-millionth the brightness of their stars -- to be seen. It’s like trying to see a fly fluttering around a streetlight.

Now, astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope have taken the first visible-light snapshots of a planet orbiting another star. The images show the planet, named Fomalhaut b, as a tiny point source of light orbiting the nearby, bright southern star Fomalhaut, located 25 light-years away in the constellation Piscis Australis. An immense debris disk about 21.5 billion miles across surrounds the star. Fomalhaut b is orbiting 1.8 billion miles inside the disk’s sharp inner edge.

"Fomalhaut b sits in a frigid location, but it's not too different from that of Neptune in our solar system," says team leader Paul Kalas of the University of California at Berkeley. "Fomalhaut b is four times more distant from Fomalhaut than Neptune is from the sun, but Fomalhaut is a star that is16 times more luminous than the sun. This means that Fomalhaut b receives the same radiation as Neptune does from the sun."

Like the hundreds of other known extrasolar planets, Fomalhaut b is a gas-giant world, estimated to be no more than three times Jupiter’s mass. But astronomers suspect it might have one striking characteristic that separates the newly discovered planet from its extrasolar brethren. It may be surrounded by an immense Saturn-like ring system.

"The planet is brighter than expected for an object of three Jupiter masses," Kalas says. "If we’re seeing light in reflection, then it must be because Fomalhaut b is surrounded by a planetary ring system so vast, it would make Saturn's rings look pocket-sized by comparison. The ice and dust reflects starlight."

Perhaps the ring will eventually coalesce to form moons. The ring’s estimated size is comparable to the region around Jupiter that is filled with the orbits of the four largest satellites in our solar system.

"Fomalhaut b may actually show us what Jupiter and Saturn resembled when the solar system was about 100 million years old," Kalas says. Astronomers have long considered the Fomalhaut system as a potential breeding ground for planets because of the star’s vast debris ring.

Kalas and team members proposed in 2005 that the disk was being gravitationally modified by a planet lying between the star and the ring’s inner edge. This disk is similar to the Kuiper Belt of comets that encircles our outer solar system. The Kuiper Belt is our solar system’s attic, containing a range of icy bodies from dust grains to objects the size of dwarf planets, such as Pluto.

Circumstantial evidence for their planet theory came from Hubble’s confirmation that the Fomalhaut ring is offset from the star’s center. The disk’s sharp inner edge is also consistent with the presence of a planet that gravitationally "shepherds" particles within it.

Observations taken 21 months apart with Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys show that the object is moving in an orbit around Fomalhaut, and therefore, is gravitationally bound to it. The exotic world is 10.7 billion miles from its host, or about 10 times the distance between Saturn and our sun. The planet is unlikely to harbor life because it is too young and too hot. Fomalhaut is a relatively young star, only 200 million years old.

Kalas and his team plan follow-up Hubble observations in 2009 to further study the Fomalhaut system.

"We hope those observations will greatly refine what we know about Fomalhaut b’s orbit," Kalas says. "New measurements of the brightness at various wavelengths also will help in deciphering the physics that makes Fomalhaut b shine."

Perhaps future observations will turn up more planets. Fomalhaut b may be the outermost planet in a whole solar system of planets, just as Neptune is in our solar system.

Astronomers, however, may have to wait for the James Webb Space Telescope, slated to launch in 2013, to find out whether planets in the Fomalhaut system could sustain life.

"We'll probably have to wait for the James Webb Space Telescope to give us a clear view of the region closer to the star where a planet could host liquid water on its surface," Kalas says.

Donna Weaver

Space Telescope Science Institute