NASA’s Jon Olansen, Jenny Devolites and Ben Asher share technical stories and discuss storytelling technique with Storytelling Strategist Johel Brown-Grant.

Johel Brown-Grant: Technical stories are about humans working with technology, and we want to make the story more about the human experience with the technology and not just about the technology itself.

Deana Nunley (Host): Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps – a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast featuring interviews and stories that tap into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

Storytelling is considered to be one of the best ways to capture and share organizational knowledge and lessons learned. This is the second segment in a two-part series on technical storytelling, and today we get to hear a couple of stories from members of NASA’s technical workforce. At the conclusion of their stories, the NASA storytellers will get feedback from our guest expert on storytelling.

The first story comes from Jon Olansen and Jenny Devolites at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Jon currently serves as the Production Manager in the Gateway Program and Jenny is the Systems Engineering and Integration Lead for the Gateway Production Office. They previously held project management and systems engineering and integration positions for the Morpheus Project and Orion’s Ascent Abort-2 flight test. Let’s listen.

Jon Olansen: Our story today is set amongst the backdrop of two in-house NASA flight projects that we had the opportunity to lead to successful conclusion — the Morpheus Project and Orion’s Ascent Abort-2 flight test. Through both, we gained substantive insight into effective implementation of lean development strategies and management techniques, and we got to work with rockets.

Jenny Devolites: I like how it makes us sound like actual rocket scientists when you say it that way.

Olansen: Indeed, it does, but I’d really rather give that moniker more directly to the hard-working members of our teams. Any case, to begin our story, consider what we set out to accomplish. As you as a project manager start your project, first, know your mission. For our first mission, we pursued capabilities necessary for a human base on Mars. If you’ve seen the movie, ‘The Martian,’ you may picture a base on Mars with a lab and a habitat and rovers and an ascent vehicle.

Devolites: And don’t forget an astronaut marooned there.

Olansen: Too true, but all located in close proximity to each other on the surface. In reality, how will we get them there, along with the humans to live and work there? The two projects we highlight today advanced our knowledge of some of the technologies, hardware and software we need to get there. But just as importantly, we evolved our understanding of what it takes to lead a team who is designing, building and testing all of these capabilities.

Devolites: So, Jon, we started working together back in 2010.

Olansen: Wow. Has it really been a decade already?

Devolites: It goes fast. So, back then we had the opportunity to learn how to develop and test an autonomous lander from the ground up on a project called Morpheus. And this project had all the elements of an exciting adventure. We had high pressure systems. We had cryogenic fluids. We had flames. We had powerful lasers. We had cranes. We had mosquitoes. We had failure modes. And we even had a big red button to abort the flight and drop the lander out of the sky. So, that was all very exciting, but this project wasn’t just about developing a lander, but also about learning how to bring together a group of smart, motivated, passionate engineers, and turn them into a high performing team, under challenging circumstances and in a short period of time.

Olansen: And with almost no budget, really.

Devolites: Right. So, with that background, we were chartered to explore how we could apply lean development approaches to this activity with an eye towards learning how we could find ways to move projects along faster on the path to Mars exploration.

Olansen: And then, after Morpheus, we continued to evolve lessons of lean development, applying them to the design, development and integration of a test version of the Orion crew module for the Ascent Abort-2 flight test. So, for this second mission, we were actually going to launch on a booster built by Northrop Grumman that was used to carry the crew module and the Orion Launch Abort System up to 31,000 feet and execute an abort flight test with millisecond accuracy, by igniting a powerful abort motor to pull the crew module away from the booster and then allow it to splash down in the ocean. A critical safety test that would demonstrate the ability to save the crew, if needed, during ascent. That flight test was accomplished successfully just a little over a year ago in July of 2019.

Devolites: 2019. Right, so we really have been working together for a decade, Jon. Wow.

Olansen: Unbelievable.

Devolites: And still going. So, over the course of these two fantastic projects between Morpheus and Ascent Abort-2, we noted, as many others have, that there were a number of attributes that were necessary to success, such as a competent workforce and management support, funding, all of those things. But what we found is that there were three important keys to how we achieve success. So, first one was iterative systems engineering. The second one is balancing risk and rigor, and then the third one we want to talk about today is team culture.

Olansen: So, the Morpheus Lander was envisioned to be a full-scale robotic lander prototype. It was to have a flight control team and a pad crew like any typical rocket and then be commanded to launch, soar straight up 250 meters into the sky, and then fly an approach and landing trajectory similar to a planetary approach, and approaching a hazard field that we had set up to look like a part of the Moon, with boulders, dust, craters and all, and do it all with a completely autonomous flight trajectory.

So, there was no remote piloting, and instead there was a built-in capability to detect and avoid obstacles on the surface, thereby creating the ability to land components in relative proximity. We had these key technologies that needed to be matured into capabilities, that could be then incorporated into future missions. So, with Morpheus we started off working with the motto, ‘Technologies offer promise, but capabilities offer solutions.’ This meant that we were seeking to take these individual technologies being worked in labs across the agency and integrate them into a relevant environment, and work out the kinks across a high-capability system. We designed and built the first Morpheus Lander vehicle on a minimalist budget in only seven months, and then spent another year and a half incrementally adding capability and testing it. We did cold flow testing, static hot fires, tethered flight tests.

Devolites: Lots of tethered flight tests. Yeah. So, what Morpheus gave us, all of that gave us the opportunity to do, was integrate technologies together into a fully functioning flight system, and then refine them by learning about the system interactions. So, for example, managing center of mass of the vehicle was critical to maintaining stable flight performance, and then the distribution of propellant between the tanks affected that center of mass. And another example, the ability to provide flight control under windy conditions was completely tied to how well the LOX methane attitude control thrusters stayed on, and the longer they stayed on the hotter they got. So, we had all of these integrated system issues that we only found by testing these together. So, we learned to balance these technology capabilities across the integrated system. And we learned these things, not by long periods of requirements development and analysis, but by prototyping and testing, and then repeating that cycle until we had reached our goals.

Olansen: And then on the AA-2 crew module, we had no opportunities at all for flight testing, but we applied that iterative systems engineering to our integrated hardware and software development, using a lab that had increasing fidelity of not only the hardware components, but also the software development and simulations.

Devolites: Can you believe we ran over a thousand tests in that lab with our little team?

Olansen: It is amazing that over time we ran over a thousand tests. And that lab is really where we got the bang for the buck on iterative systems engineering. Each test cycle we had, had specific objectives. So, it was very much a build-a-little, test-a-little environment, and as a result of that iterative systems engineering approach, our flight software was actually 90 percent complete at our Critical Design Review, well ahead of the norm. And that allowed NASA to accelerate the launch date of AA-2. We ended up actually delivering the crew module completed and certified, as well as a separation ring it was mounted to, six months ahead of schedule and several percent under budget.

Devolites: I hear you say that, and it sounds like such an accomplishment, just that part because it’s very hard for any project to deliver ahead of schedule and under budget. So, that truly felt like an accomplishment for us. And so, that leads into our second key lesson, which was about risk versus rigor, because that fed so much into how we were able to achieve that. So, we have a couple of examples we can talk about. The first one I wanted to talk about is from an early team activity that we used to evaluate the scale of rigor for Morpheus.

And I’ll always remember the lesson we learned at this early team retreat that we had. We got the leads together and we were trying to establish how much rigor we should put in for all kinds of topic areas across the project, like how much paperwork should we do, how much rigor and requirements development, how much test documentation? So, I drew an illustration on the white board, and we had low rigor on the left and high rigor on the right. And we just asked everyone, ‘Go plot your initials based on how much rigor you think we should have.’ And so, it turned out to be this unexpected teaching moment or learning moment. We ended up with initials all over the map. And so, our big takeaway was that no matter what point we picked, we would have some team members who thought it should be more rigor and some who thought it should be less. There was just no central number. And so, knowing this made it really apparent that we would expect to have a push and a pull as we went across the project life cycle, and that it would take a lot of work to get the team on board with any given decision that we made about project rigor.

Olansen: And so, it was a continuous effort, Jenny, as you say, to really guide the team forward in the approach that we wanted to take relative to rigor, and yet our selective approach was always rooted in our risk posture. And there was a zero-based approach that we would do in all of the areas that you referenced, in deciding what we would implement on the project, but it was all done with our risk posture in mind. So, the second example that we talk about in this arena is risk. And we had numerous opportunities to learn and improve from test failures as we would test with the vehicle and then make changes and test again, but none were more spectacular than when we had our first opportunity to fly Morpheus at our specially built hazard field at the north end of the Shuttle Landing Facility at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Natural sound: Abort, abort, abort.

Olansen: So, abort is not what you want to hear in testing, but for us on our 27th test with a live rocket engine and our second attempt at a free flight at KSC, while streaming the test live for thousands of followers to watch, we had a failure that caused our vehicle to crash and burn. Two years of work and it could have been all for naught. The loss of a Morpheus vehicle was a pre-declared risk, consistent with the low-budget R&D approach that we had employed, but still it was disheartening.

So, we gathered at the crash site that day. I pulled the team around and talked to the team, told them that we were not done. We would persevere. We would pick up the pieces and come back to fly again. We had management’s backing. We, again, overtly addressed balancing risk versus the amount of rigor we would employ in building the next Morpheus vehicle. We would increase rigor in some areas, but not across the board. We were still very judicious in using risk to identify where we would improve our risk posture, our robustness, our redundancy, in order to get the most value out of flying the Morpheus vehicle. In another seven months, we did rebuild the Morpheus vehicle and between the two vehicles we flew a total of 63 times, including 13 fully successful free flights over the Shuttle Landing Facility at KSC.

Devolites: Well, and even now we hear about a number of LOX methane engines being developed, and also the addition of precision landing instruments to future Moon and Mars landers. And so, I know we, and the rest of our team are also so proud that we could help contribute to that knowledge base and technology advancement across the board. It’s so great to hear about those achievements. So, we took those lessons on risk versus rigor into our AA-2 crew module development and testing. And this time we knew we would need to increase the level of rigor during development and weigh the risks differently, given that the Ascent Abort-2 flight test was critical for enabling future crewed Orion missions. The process we followed was the same as on Morpheus. We just adjudicated the risks differently based on that mission. And so, we still had daily decision making based on risk, and we enabled a leadership team that could quickly adjudicate risk and maintain aggressive decision velocity.

So, that leads into our third key to success, which was establishing and maintaining a specific team culture. When we bring together any team, every individual will come from a different background, and have a different set of experiences and perspectives to bring to the table. So, on a large scale, we may look at merging cultures across international boundaries or different NASA centers, but organizational cultures are different even down at the individual level within a branch or a division. And so, a critical part of bringing together a team is merging those cultures so that the group has a more common set of expectations for how we will behave, how we will do business and how we handle conflict. And we saw some of that when we talked about scale of rigor earlier and trying to get the team on board with any specific decision that we make.

Olansen: And so, for both projects, we worked hard to create an environment of open communication up and down the chain. We established at the beginning and throughout those projects a set of tenets that we would follow as a team to ensure that we continued to address the behavior and the culture within the team as it was executing both projects. Both projects were multi-center, where we led work from three different NASA centers on AA-2, and actually eight different NASA centers worked some for Morpheus. That’s a lot for small projects.

Devolites: We instilled a belief that the team members could take the risk of failing forward, like what happened on Morpheus, without putting their careers at risk.

Olansen: We created a mindset where we all own system performance, breaking down stovepipes and encouraging ownership at every level. It is not lost on us that for both of our projects, the designers were also the flight control operators. So, owning responsibility for flight performance was a very tangible driver.

Devolites: We also would not allow finger pointing. Every subsystem would have a bad day at some point in the design cycle, so it was important for everyone to recognize that.

Olansen: And we pushed decisions down to the lowest appropriate level, so people had authority commensurate with their responsibility.

Devolites: Jon, I think we could go on and on.

Olansen: Which I have a bad habit of doing.

Devolites: But to wrap up this short story, so these two projects, the Morpheus Lander and the Ascent Abort-2 crew module, reinforced three key lessons for success on the road to human spaceflight: the benefits of iterative systems engineering, balancing risk versus rigor, and creating a united team culture all in a manner consistent with meeting the defined mission.

Olansen: And we are bringing these lessons forward and now implementing them within the Gateway Program, as we speak, and we look forward to continuing to apply these lessons on the journey to the Moon, Mars and beyond.

Host: Jon and Jenny, thank you for sharing this story and your experiences with us.

Olansen: Deana, thank you very much for the opportunity. It was great to be able to try a different format to tell the experiences that we’ve had over the past several years.

Devolites: Yeah. Thank you. It was a really, really fun opportunity for us to talk about things that we love.

Host: Yes, that passion for your work really comes through. And we’ve got another fun opportunity. Storytelling strategist Johel Brown-Grant with the U.S. State Department joined us in the first segment of this two-part series on technical storytelling and has graciously agreed to offer feedback and share his expertise. Johel, what are your observations of the story we just heard?

Brown-Grant: Well, Deana, this has been a great experience to listen to Jon and Jenny’s story. There were many things that they did that were really commendable. I had a great experience listening and getting into the world that they were creating with their stories. I would like to share a few points of feedback with Jon and Jenny to kind of give them a little bit of an idea of things that they might want to consider for future stories.

I want to start off by saying that one of the things that I liked about the story that they brought forth is how exciting and action-packed it seemed. What I liked about this story was that there was a lot of things that were happening, different moving parts, so it made this story very engaging and very exciting to follow. There was something happening at every turn.

Another thing that I liked that they did was that they started right off the bat naming the audience. Identifying the audience, especially in technical stories is really good because it allows those audiences that are listening to kind of figure out, well, where do I place? How do I place myself within this story?

And the other thing that I liked about their story was that you could tell when they were telling this story that it was the result of their own experience, their personal experience going through all of these events, all of these problems and issues they were trying to solve, and that’s another thing that is very important. To have your experience reflect in this story is an important point to make that connection with the audience.

Also, one thing that was really great, and I actually enjoyed about this story, was the banter between Jon and Jenny and the use of humor. There were humorous moments in this story and that made it really, really interesting.

And then, finally, one thing that I love that they did was that they included special effects in one of the stories, and that made it really interesting because the story, it takes you from not just listening to their words, but listening to the effects, and that helps the listener to create a movie in their mind of this story they’re creating.

I just want to end my observations here with a few other things that I wanted them to consider. I think that maybe one thing that they could consider for next time is maybe having a shorter story or consider the overall length of this story. Their story was very interesting because it had three important sections and each section, I consider it to be its own story. There was the section on the iterative system engineering, the balancing risk, and the team culture. For each of those sections, they really had what I consider a contained story, so my suggestion would be that they maybe look at that as a way of having separate vignettes that are part of a larger story.

I think that the story was very interesting. There were a lot of parts that were moving in the story, but that also added to the complexity of this story. So, one thing they might want to consider is try to simplify this story, and in shortening the story or chunking the story in segments, they can achieve that simplicity.

So those are some of the things that I noticed in this story that were really appealing to me and some of the things that I think they might want to take a look at for either a revision or for further stories that they might do.

Olansen: Johel, that is fantastic feedback. I really appreciate you listening to our story and critiquing it, providing us some insights on how we come across and things that we can consider. A question for you in just what you’ve laid out thus far. You talked about the audience, knowing the audience, and talked about trimming the story, cutting it down both from a length and a complexity perspective. For us in trying to tell this story, talking to project managers, systems engineers and people who are also building complex systems, trying to tell the story of our experience and how it evolves through multiple projects, there is a complexity to it and a length to it. Can you give some more feedback on how we might take that information and shrink it down and actually accomplish the suggestions that you’re making?

Brown-Grant: Thank you. That’s a really good question. When I was listening to this story, Jon, I noticed that for example, one of the stories is about the Morpheus lander. One suggestion that I was thinking that you may want to consider is when you are working on your story, take the Morpheus lander as its own story. One thing that would be interesting would be to sort of just tell that story from your perspective and her perspective, bring your emotion into it, make it exciting, and then when you finish that story, you could say, ‘These were the lessons that we learned from that experience.’ Or you can do it the other way. At the front of the story, at the beginning, you could say in this story, ‘We learned the following things,’ and then you tell this story. So that allows you to packet that story as its own unit.

In a situation like the one that we’re talking about now, I would say, then you could have a pause and then announce to your audience, ‘OK, we have a second vignette or a second story that illustrates this particular concept’. Then you get into that short story, and then you end that story with a reference back to the points you were trying to make. For example, the second story was about balancing risk, so you could talk about the story only from that perspective. This achieves a number of things. One, it helps the audience in terms of their mental models of what you’re trying to set up, and this is very important with technical audiences. When you deal with technical audiences, it’s all about mental models, whether it is for processes or for procedures that you’re trying to put forth. So when you shorten the story like that, and you make the story its own unit with its own sort of narrative world, you allow the audiences to develop a mental model for that specific issue, in this case, the iterative system engineering that you were talking about.

The last point I want to make about this example that you have is that the story has to be very targeted, very specific to an issue, and you do accomplish that in each story.

Devolites: So, a couple of the takeaways, Johel, that I got right away from your feedback were that we went a little too long and overcomplicated it. I just thought that was fitting only because like Jon mentioned, in terms of how we apply this to actually interacting and communicating with our teams and how important that is, those are two things that engineers have a bad habit of doing, and so it’s interesting. We really tried to take a look at this, and this was a new format for us to talk about our experiences and our lessons learned, and so trying to figure out how to package it so it’s good, it’s good feedback to know that we need to go even further that direction in terms of simplifying it and breaking it into chunks.

I think one of the things that we tried to do in planning for the story was reach the audience through multiple examples. And so part of how the story got more content in it is just like when you learn to write an essay and you have a topic sentence and you have supporting material, and so I think that was part of how we went about it was to try to provide multiple examples for each of the type of themes that we were covering. And so that requires more introduction and it requires more interleaving of the stories, but it sounds like what you’re saying, though, from a receiving side, we would still be better off by breaking those into separate chunks and then bringing them back together at the end.

Brown-Grant: Yes, Jenny, you’re right. That makes a lot of sense. It’s better to chunk the stories, and then in the end you give a summary of the points that you were trying to make with each one of them.

One of the things that I wanted to talk about that I mentioned briefly a second ago is the use of sound effects. One of the things that you guys did that was really interesting was adding a sound effect in your third story. That was really helpful because it allowed the audience to not only listen to your words, but also to get an idea of what the experience had sounded like. So if you could do more of that, put sound effects in other parts of the stories, maybe not a lot of them, but a few to kind of illustrate, to give folks a way to even enrich that image that they’re creating in their head of the story, that would be really helpful because since we’re in an auditory medium, you want to bring as many elements to help people form an idea of the story. So, using different sound effects in your story will allow this story to come alive and it would breathe new energy into this story and make it even more exciting for the audiences that listen.

Olansen: I really like that comment, Johel, that we talked quite a bit about whether or not to include the sound effect that we did include and weren’t sure how that would come across. Thinking back now, there are so many different sounds, rocket engine firing.

Brown-Grant: Yes.

Olansen: The crash itself.

Brown-Grant: Absolutely.

Olansen: Things like that that absolutely could be added and I think get that feel out of the story that you’re talking about.

Brown-Grant: Yes. That will take your story to a whole other level. So, you do want to consider that for the future. That would really make it interesting.

Devolites: Yeah. I like that. I’m trying to figure out how I can get more sound effects into my presentations at work. You think that’ll be OK, Jon, if I start putting some Morpheus and AA-2 audio in the background?

Olansen: I think that’d be fantastic.

Devolites: I like it.

Olansen: So, one other area, Johel, that I’d like to discuss with you. You talked about emotion tied into the story, and again, we do talk about our experiences in different forums and it’s usually longer, but we talked preparing for this about the message that we wanted to send. There is absolutely a passion that we both have for the work we do and why we do it and what we’re trying to improve as we do it, and so from your feedback, I take that that passion kind of came through. But my question for you is, are there different ways or better ways we could word some of the things that we said or that we could approach telling the stories that would even be more effective in conveying that emotion, that passion?

Johel Brown-Grant: Yes, that’s a great question, Jon. I think that one of the things to consider when you’re trying to bring the emotion into the story, the first thing is to keep in mind that if you can tell this story from a first- person perspective like you did, talking about it as your experience, what happened to you, that is very important.

Then the other thing about emotion is to talk about feelings. Feelings are an important part of storytelling because that’s where you allow the audience to connect with you. They will connect their feelings to your feelings when you tell this story. For example, when you talk about the third story where you talk about the flying Morpheus and how at one point during the test flight, I think it landed and crashed. What would make that story really interesting from an emotional perspective is for you to talk about how you felt or how the crew working with you felt, talking about what you saw in their expressions, their faces, things that they said, bringing forth that human experience, that feeling of happiness, excitement, sadness. That enriches the story because it makes the story, especially from a technical perspective, which is what we’re talking about, it makes the story more human.

Technical stories are about humans working with technology, and we want to make the story more about the human experience with the technology and not just about the technology itself because the technology itself doesn’t have the human properties. The human properties come from our experience using it. So I think that if you can talk about more about how you feel, how you felt before, what you were expecting when you began, how you felt when you were able to achieve or not achieve the goal, and insight in your mind as you’re going through the experience as you’re telling people what happened to you, that’s what makes the story really rich and really exciting for the audiences, and it helps them to, like I said before, connect to what you are saying from a human perspective.

Olansen: Thanks, Johel. I’m actually taking notes now on how to give feedback to my employees. This is great, very specific, tangible feedback that we can use in the future.

Devolites: And I just want to echo what Jon said. Thank you so much for listening to our story and for giving us some very specific feedback. I definitely got some good takeaways from that in terms of how to use that in the future.

Brown-Grant: Well, I really appreciate the opportunity to talk to you about your stories, and I want to commend you for the work that you have done. I had a great time listening to this story. I had a great time listening to the experiences you brought to this story and I really want to encourage both of you to keep telling stories because talking about your experiences in a storytelling format enriches what you do and it allows you to discover connections with your audiences that you might not have been able to make before.

Host: And now let’s listen to a story from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Following the story, Johel will join us again to share his observations.

Ben Asher: Hey, so my name’s Ben Asher and I’m a Trajectory Analyst supporting NASA’s Launch Services Program. My job is to help get NASA’s robotic payloads from the ground up to orbit. I’m kind of the Google Maps for space.

What I want to share with you today is how I help come up with the best route to where the satellite wants to go, and I’ll do that by also planning a road trip to Disney World at the same time. There are a lot of similarities between planning a road trip and spacecraft trajectory. Usually though, a lot of decisions you need to consider are already made for you when you go on a road trip. For example, if you already have a car, you’re not going to buy a new one for this road trip, right? But for our satellite missions, that’s not necessarily the case. So, for simplicity, we’re going to start from scratch. What are the things you need to consider for a road trip? We’ll start with the who, what, where, when and why sort of questions. I’ll start with why or what. So obviously, you want to go Disney World because it’s fun, right? ‘Happiest place on Earth.’ But for our satellite missions, you want to do some sort of specific science. You want to collect some certain data and you need to go to a certain place in order to do that, right?

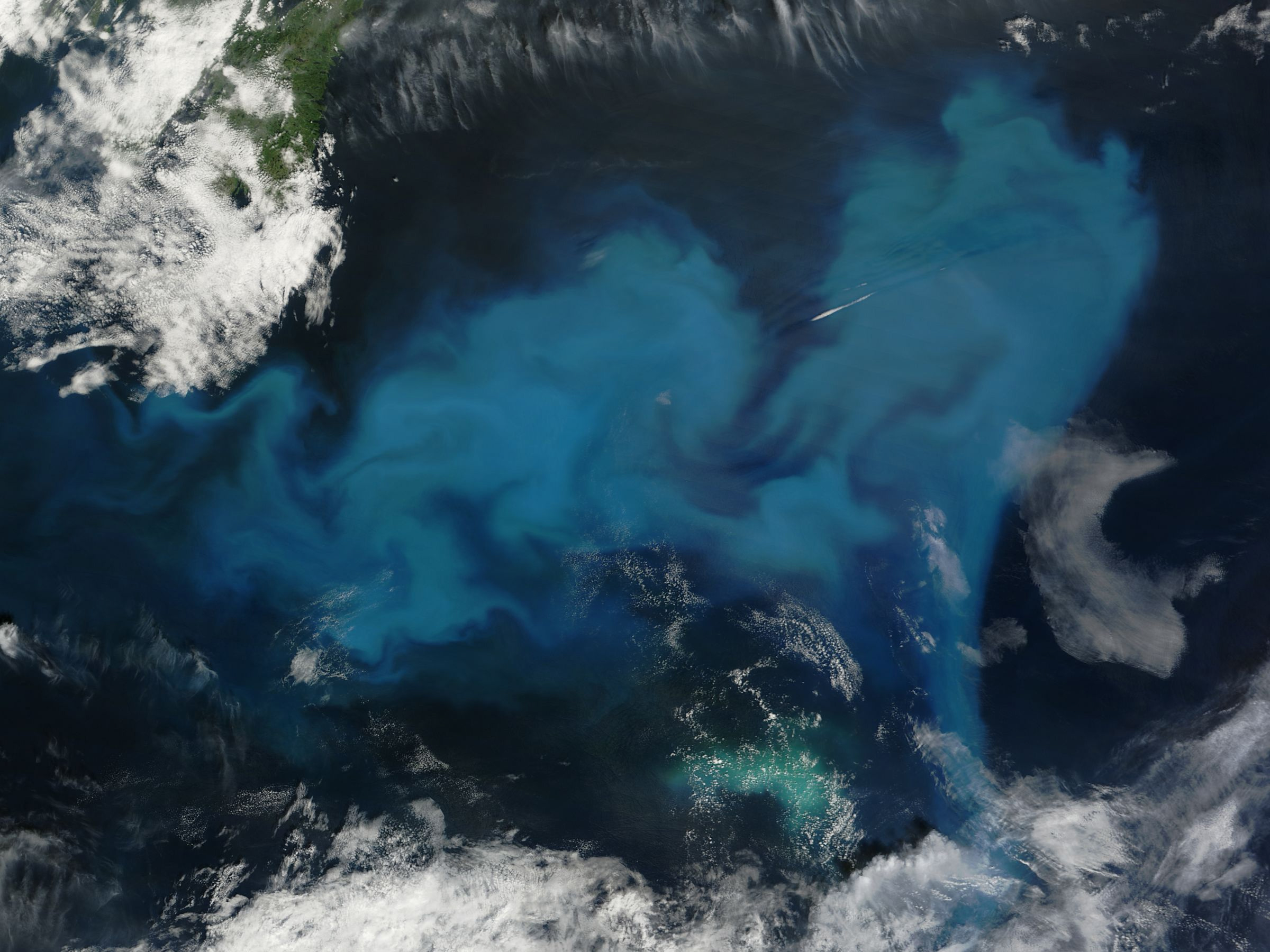

If you’re doing, I don’t know, looking at Earth’s oceans or land, you’re going to be probably in a low-Earth orbit. We have some weather satellites in a geostationary orbit. We have science that we want to do at Mars. Then there’s other things in Jupiter, so on so forth. Next thing to consider is where you’re starting from and where you want to go. Obviously, we want to go to Disney World for our road trip but where do we start from? Right? To make it simple, I’m just going to say we’re going to start from the Kennedy Space Center.

For our spacecraft mission though, where we’re going dictates where we launch from. We have two launch pads that we mostly work with, Kennedy Space Center for launch sites as well as Vandenberg Air Force Base. From Kennedy Space Center, you can mostly only launch east and from Vandenberg, you can only really launch south or west. And we use that for our polar orbiters, and I’ll get into that a little bit. For our example, for both cases, we’re just going to start our road trip from Kennedy Space Center as well as our space trip.

Next thing to consider is, who’s going? Or also what, in this case. Is it just you going on the road trip? Is it your family? Is it the entire sixth grade class? That decides the size of the vehicle that you need to go on the trip. The other thing that dictates the size of the vehicle is how far you need to go. The trip from Kennedy Space Center to Disney World is really not that far. But if you’re going from Kennedy Space Center to Disneyland and you needed one tank of gas, you might need a much larger vehicle, even if you’re driving just yourself because you need to take all that extra gas with you. Right?

Similar to a launch vehicle, we have different payloads, different sizes and they’re going to different places, right? Even though you’re going to Jupiter and you might only weigh a thousand, 2000 kilograms, which is more than enough for some of our smaller rockets, in a low-Earth orbit because you’re going so much further, we need to buy these bigger rockets.

Another thing to consider is how sensitive or risk-adverse a payload is. For example, if it’s just some bunch of bros going over to Disney World, they could maybe rent the Jeep, have the top down, doors off, wind blowing. It’s loud. It’s uncomfortable for some, but they don’t mind. But what if you have a sensitive payload like a baby? Baby would be very unhappy in the Jeep in that scenario, so you probably want to get a nice, quiet ride, tinted windows, healthy air conditioning, right? Maybe even a TV in the headrest for some spoiled toddlers, yeah.

And so again, the same thing with our satellites. We have these different payloads that are taking really specific measurements and it’s high accuracy, high precision and it’s very sensitive to the ride up to space, right? Because our launch vehicles, it’s almost like a bunch of explosions channeled out the back of the vehicle so that the rest of the vehicle goes up. Can shake the spacecraft quite a bit. Those are all things to consider.

Next thing to consider is when, right? And we can break this into two portions. We can talk about what time of year and then what time of day. For our Disney World trip, if you’re going with a family, for example, you probably need to consider the kids’ school schedule, right? You can’t just go in the middle of the school year. It’d be irresponsible. I mean you can and maybe it’s not irresponsible. I’m not judging, but in general you would want to try to go in maybe the summer or winter vacations. There’s a brief period of spring break and fall break but you have a little more wiggle room in the summer and winter, right?

What we call that is the launch period. The time of year. For example, if we’re going to Mars, there’s kind of a specific time where Earth and Mars line up to make it possible. And you think about that as a football player, like a quarterback throwing to a passer. You have to lead the passer so that the ball and the passer get to the same spot at the same time. Right? So that’s kind of what dictates our launch period is that specific timing.

Then for launch window, that’s kind of the time of day. For a Disney World trip, you don’t want to get to the park at 10 p.m., right? You show up, get there for the fireworks and then have to turn around and come home. That’s not a whole lot of fun or in our spacecraft scenario, not a whole lot of science, right? So yes, we can go during the summer, but we also in the summer want to get there maybe at park opening at 9 a.m., so that kind of dictates our launch time on each day within our launch period.

And so, you’ve probably heard of launch window and a launch window can be instantaneous. So that means you want to get exactly there at 9 a.m. or you can have some wiggle room, right? Maybe little Timmy is throwing a fit in the morning and you’re 15 minutes or so behind. Well, are you going to just scrap it and wait till the next day? No. You have some wiggle room. You can put up with that 15 minutes. So, you just show up 15 minutes later. You still get a lot of good fun, or science, right?

There are some external factors to consider as well. Like weather, heavy traffic or construction on route and then of course the rules of the road. Let’s start with weather since that’s pretty straightforward. Eventually the rocket gets up to space and weather doesn’t matter. But along the way, you can have really powerful upper-level winds. They can push you off course or even break the rocket. Also, Florida is the lightning capital of the U.S. and that’ll affect both our Disney World trip as well as our launches. And there are some other weather things to consider as well but those are kind of the main ones.

If you’re considering traffic or rush hour, they may move your departure time a little bit, right? It doesn’t make sense to drive for two hours and get there an hour late if you could just wait at home for an hour and then drive, right? Similar to launch vehicle, we have to look at where all the other satellites are, right? So, it’s not necessarily rush hour, it’s more of a merging onto the highway sort of problem because imagine, in your drive to Disney World, you can’t touch the brakes. So, you’d have to know where all the other cars are at all times at all intersections and when you get onto the highway and you have to time it perfectly and thread the needle between everyone. That is obviously very challenging but luckily space is a lot bigger and a lot less populated than our roads. But still, that is something we have to consider. And if you have, say, a 30-minute launch window, you may have a couple 30-second blackouts where you can’t launch because you could be getting close to other satellites.

Sometimes you’ll have construction on route. And what that does is block off the route you’d rather take, or maybe puts you on a slight detour, or maybe it narrows it down to one lane so you’re kind of stuck going a certain way for a bit until you can get back on track. And generally, it’s not the most optimal route, right? To end up at Disney World but sometimes it’s something you have to deal with. Again, similar to launch vehicles, we have to consider where we’re flying. I kind of alluded before we have the two launch sites in Florida and Vandenberg, but we don’t really have anything in the middle of the country. That’s because we care where we’re flying over, right? We don’t want to fly over populated areas. And so that’s why we launch east from Kennedy Space Center a little bit north, but not too far or else we start flying over Newfoundland, Canada, Maine, or we don’t want to fly too far south because then we start running into the Bahamas. And similar at Vandenberg, it only launches south or west, but they do have to worry about the Channel Islands to the southeast of them. We call those IIP constraints, instantaneous impact points. So, if the rocket were to have a failure at any point in flight, we want to make sure it doesn’t land anywhere populated.

You also need to obey the rules of the road along the way. Instead of driving rules, the launch vehicle is more driven by the laws of physics and the capability of the rocket. One example here is the speed limit sign, right? So, it might be a recommendation to some, but it is a limit, especially for the launch vehicle. But instead of a speed limit we have this Max Q constraint. You might’ve heard the announcer on launches. They’re very focused on if we made it through Max Q. That is the portion of flight that has the maximum dynamic pressure pushing on the rocket. And that’s when the rocket has the most forces exerted on it. And that happens generally around the time where it starts going transonic or transitioning through supersonic speeds, transonic. And that’s a very important constraint. What the rocket will do is they’ll let off the gas a little bit and not go as fast through that portion of flight and then once they get a little higher in the atmosphere, it starts getting a little thinner, they can put the foot down on throttle and keep going.

Our rocket doesn’t get us all the way to our destination. It’s more like getting us onto the highway. The satellite has to plan its whole trajectory all the way from ground to its final destination and the launch vehicle’s really only a small portion of that. But it’s a very complicated portion because driving on the highway is much simpler than navigating all the twists, turns and rules leading up to getting onto the highway.

Once we consider all those points, we can then map out our trip wherever we’re going. Whether that’s Disney or space. When it comes to the day of launch, we’ve considered every possible scenario that could affect our trajectory because once the rocket lifts off, there’s no more changes to be made. The flight computer knows its course and will follow it to a T, and it’s our job to make sure the mission is successful.

Host: Ben, thank you for sharing your story.

Asher: Hey, no problem. I love sharing this stuff.

Host: Let’s bring storytelling strategist Johel Brown-Grant into the conversation. Johel, what’s your reaction to Ben’s story?

Brown-Grant: Hi Ben. This was a wonderful story. I really, really liked what you talked about. Your story is very interesting because it’s a journey, and that’s one of the types of stories that you can talk about when you’re doing storytelling. The story of the journey is always very interesting because it takes the listener from one point to another, and that was what you were doing with the story. So, I was on the journey with you in that story. And I thought that was really, really interesting and really, really cool.

One of the things that you did that I liked was that you were very engaging when you were telling the story. And I could tell that this was something that was not only important to you, but very near and dear to your heart. So, that was really, really nice – that level of engagement that you brought to this story, I could tell that is something that you were very invested in.

I think that one thing I would suggest to make the story even more interesting and more attractive is that, Ben, if you could maybe tell this story or a story like this in the future more from your point of view like, ‘This is what happened to me.’ For example, when you’re telling this story, I think what you could do if you want to retell this story in the future for another audience, is to say, use the I pronoun. This is what happened to me. This is how I went about on this journey.

If you tell the story from that perspective, then when you’re talking about the different things that you did along the way, that will actually make the story even more compelling. Because then I as the audience will be listening and going on that travel with you, but with you experiencing it. And I actually wanted to pause for a second before I give you some additional feedback. I wanted to ask you, is this for a purely technical audience, or is it an audience that is technical and nontechnical? Could you give me a sense of that, Ben?

Asher: Yeah, I can do that. I guess when I was putting this together it was for both. It was part of a tech talk series that we’re doing in our program. And, essentially, we were going around the program and talking about each individual group and what they do and how they contribute to the larger picture.

Brown-Grant: OK.

Asher: In addition to the normal engineering roles, all the different disciplines, you also have administrative or business folks also listening. And so, I was trying to appeal to everyone. And that’s funny that you said to include yourself in the story and to make it more immersive, because I was focused on the audience so much. I was trying to jump into their world like, ‘Well, how could this apply to you or you or you?’ And sometimes you just need the human connection.

Brown-Grant: That is very cool. And here is one thing Ben, that you’re thinking is spot on. How do you get the audience to become a part of this story and to take this story and make it a part of their own. But the thing about that is the way to do that is to make it your experience. Because for them to make it a part of their own, they need to see, they need to latch onto your experience. If you tell this story as your story, then every audience that you tell that story to, they will find something in that story that applies to them, but they need to hear it as your experience. Of course, you can tell a story that is more like a testimony of something that happened to somebody else. But stories that are more powerful are the stories that are our first-person accounts. And the way you were telling this story, I kept thinking, ‘Wow, this is very interesting.’

I wonder as I listen to this story, what were those moments in this story where you felt doubt, where you felt excited, where you felt that that, ‘Man, I’m actually getting something done here.’ So, if you could bring – and this is what I mentioned in the previous conversation – a little bit of that emotion of how you felt as you were going through this. If you bring that more into this story, that provides even more of an opportunity for the audiences to then connect with you. The connection comes in many ways from that emotion, from that emotional part. I as a human being, I experience feelings and you experience feelings. And if you’re talking about those feelings in this story, then it’s easier for me to connect to your story and say, ‘Wow, that happened to you could also happen to me,’ or ‘Would I have reacted the same way if I had gone through what you were going through?’ So, I think that is really interesting and really important.

The other thing that I think that I wanted to give you as a feedback is, and this is why I asked about the different audiences, because I thought, well, if it’s an audience that is highly technical, it’s a good idea to maybe use the example of Disney, but I would probably not carry it through the entire story. Because then the question is, is it a story of Disney or is it a story of the experience that you were going through? And when I say, ‘Is it a story of Disney?’ it’s because when the listeners are listening to your story, they’re trying to create a picture in their mind, a mental model of what it is that you’re talking about. So, I think mentioning Disney at the beginning does help, but I think that just for the cognitive engagement of the listeners, you want to keep them on one path. The examples that you give can be sporadic, but especially because you’re telling this story from your perspective and what is happening to you, you don’t have to use as many external examples. Those are good sporadically, but I would probably not include quite as many. What do you think about that, Ben?

Asher: That’s interesting, because it’s a hard balance, right?

Brown-Grant: Yes.

Asher: I’m working with highly technical jargon, I guess.

Brown-Grant: Yes.

Asher: And not everyone knows what all that means. I’m very intimate with all of the trajectory analysis and everything, but not everyone is. And I try to step back and think like, ‘All right, well, this is how I think of it. How can I relate that to someone who doesn’t know what this term means?’ And yeah, I definitely could have gone down the rabbit hole a little bit.

Brown-Grant: Well, I think that’s a good point. And what you’re saying is the kind of tension that people in technical storytelling face. The ideal scenario is that you tell a story to an audience that is purely technical, but as we know, there are nontechnical audiences that may listen to the story. So, what I was thinking is that it’s not that you don’t use the examples, but they don’t have to be interspersed with every single example in this story. I think that one of the things that you did really well was the definitions, where you defined the terms. And the reason why I asked what kind of audience you were working with, it was because I was thinking that if you have a nontechnical audience, for example, you can as a person telling the story, you can mention a term and say, well, so this term, you can ask yourself, ‘So what does this term mean?’ Ask yourself the question and then give the answer, kind of modeling a dialogue with the audience that does not know the term. Because you were thinking or you may be asking yourself, ‘What does this term mean?’ And then you go ahead and describe it, and then you continue this story. In other words, you have that monologue/dialogue with the audience, where you’re teaching and telling them the story at the same time. But then if it’s a technical audience that may not work, that particular style of defining the term may not work because you don’t want the audience to think that you’re being condescending to them. So, your story is interesting because you have those two audiences, and you have to find a happy medium. Does that help?

Asher: Yeah, that helps a lot. And I think some of that comes from, I was putting it together. It was a visual presentation. So, I had a lot of visuals accompanying what I was saying. So, it was very easy to show Disney on one side and the spacecraft trajectory on the other. But in talking, I see more now how that can interrupt the whole story.

Brown-Grant: Absolutely. Now that you’re saying that, that’s a really good point. So, if you’re doing this visually, it works perfectly as you’re saying, if you have the Disney example on the side. Because then you can literally show everything that you’re talking and use a travel-to-Disney illustration. And I could see where that would work really well. Now, the equivalent of that, I don’t know if it would actually work, but I’m thinking the equivalent of that then would be to insert some sort of an audio effect that would allude to a trip that you’re going on. I don’t know if technically it would work. But one of the things that we’re finding out in this conversation is that, that kind of telling the story in a visual way for an audience might not always translate to an audio format where you have to imagine everything.

The thing that I was trying to convey is that when you were telling the story, I was trying to put that picture in my head of what you were talking about. But then at the same time, I had to stop and try to picture it in my head, the Disney experience and the travel through Disney. So, I kept moving back and forth between thinking about, well, how would this look like in my head in my story of going through Disney, and especially for people maybe that have never been to Disney. And then how does this story look in my head from the point of view where you were telling what was happening to you. Do you see that tension?

Asher: Yeah. I understand that. And I really appreciate the feedback. This has been a great learning experience for me.

Brown-Grant: Yeah. I think the final thing I would say on your story is, the one thing that I would probably say that you may want to take away from this is that, just make this story, change the point of view. I would say that’s the main thing. If you do one thing, just tell this story from, it happened to me, and this is what happened to me when I was doing this or when I did this. I think that would be, if there was one change you’d make, if you made that change, that will take your story even farther. But this is a very interesting story. And congratulations, you did a really good job.

Asher: Thank you. Yeah. I learned a lot and I hope you learned something, too.

Brown-Grant: Oh, of course I did. I absolutely did. And I didn’t know that actually this technology existed. So, this was not only entertaining, but also a learning experience for me. Which is, if you get to do that when you tell a story, you entertain and you get people to learn something new, you’ve done really, really, really well.

Asher: Well, thank you.

Host: It’s been so much fun getting to hear the two of you go back and forth, talking about the story and dissecting the technique. Thank you both so much. Ben, thank you for sharing your story. And Johel, for coming in, listening to Ben’s story and giving us your expertise, and letting us know a little bit more about how we can be better storytellers.

Brown-Grant: Thank you.

Asher: Thank you.

Host: Links to topics discussed in today’s storytelling episode along with Ben, Jenny, Jon and Johel’s bios and a show transcript are available on our website at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast.

If you have suggestions for future topics, please let us know on Twitter at NASA APPEL – that’s APP-el – and use the hashtag SmallStepsGiantLeaps.

As always, thanks for listening.