Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. Join NASA astronauts, scientists and engineers on a new adventure each episode — all you need is your curiosity. Learn about lunar mysteries, break through the sound barrier, and search for life among the stars. First-time space explorers welcome.

Episode Description:

As humanity sets its sights on longer term life in space, we’re going to need ways to sustain ourselves. That’s where plants come into play! Take a tour of Kennedy Space Center’s lush Plant Processing Area with Ray Wheeler, Ralph Fritsche, and Gioia Massa – the scientists studying how to grow food in space!

Subscribe

Ray Wheeler

If you think about going into space, if you have humans, you need to provide life support.

[Song: Buttercups Bloom Instrumental by Dury]

Ray Wheeler

Humans need oxygen, we need food, we need clean water. Through photosynthesis, plants can generate oxygen, they can remove carbon dioxide. They’re always evaporating water so you can help them in purifying water if you design the systems. And of course, if you choose food crops, you can grow food.

Ray Wheeler

But there’s sort of less tangible things that could be really important. If you see things, other Earthly organisms, like plants – the smells, the odors, they’re living things, you watch them grow, you get a sense of time. These could be important in terms of the crew’s wellbeing and mental health and things like that. This is something that’s innate to our being. It’s part of the human condition.

[Theme Song: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. I’m your host Padi Boyd and in this podcast, NASA is your tour guide.

HOST PADI BOYD: You might be familiar with the idea of “astronaut food” – prepared meals and snacks we send up to space to feed our explorers. But NASA scientists are also figuring out how to grow our own food in space, so we can supplement those prepackaged portions!

HOST PADI BOYD: There’s a whole lab at Kennedy Space Center devoted to it! The “Plant Processing Area” studies what astronauts need to stay happy and healthy…and what specialized habitats, tools, and even plants, we can use to garden in space!

Ralph Fritsche

So when we look at astronauts’ health and performance, really the first line of defense for crew health is their food system.

[Song: Flowering Tree Instrumental by Dury]

Ralph Fritsche

My name is Ralph Fritsche. And I’m the space crop and exploration food system project manager for NASA. And I’m based out of the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

HOST PADI BOYD: Ralph helps run the laboratory devoted to plants in space. Right now, all our cosmic gardening is done on board the International Space Station. Ralph and his team are working hard right here on Earth so that we can eventually take plants beyond… onto our next great journeys through the solar system.

Ralph Fritsche

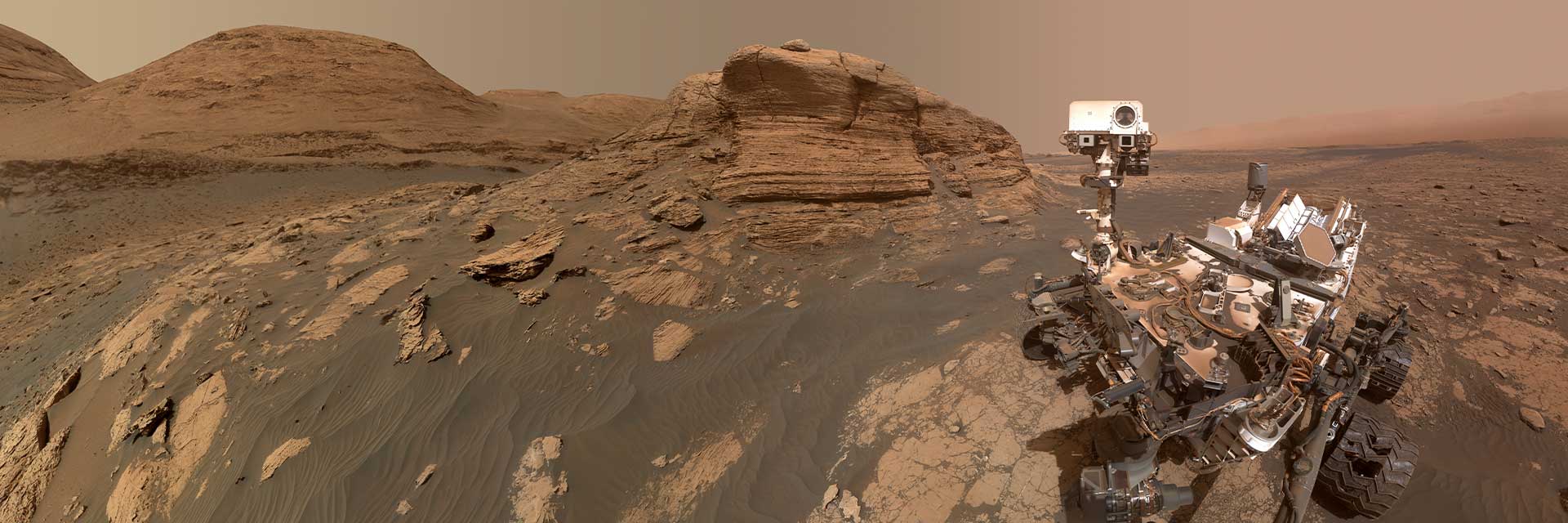

When I talk about long duration exploration missions, especially to Mars, the food that we take with us has a shelf life just like food that you get in the store on Earth. And we start to see degradation after about a year and a half on certain key nutrients. We may lose a little bit of flavor, texture, as well.

Ralph Fritsche

When I look at crop production, that is a way to provide fresh nutrients. We try to target the specific areas that we think the prepackaged food system might begin to show some negative effects with and that gives something fresh for the crew. It has aromas, smells, sensation, textures that you don’t necessarily get in the prepackaged diet.

HOST PADI BOYD: The Space Crop production team is small and mighty, taking on the exciting challenges of sustaining life in space…with the power of plants!

[Song: Zero Hour Instrumental by Dury]

Gioia Massa

My name is Gioia Massa, and I’m a project scientist in space crop production at Kennedy Space Center. So I’m a plant scientist by training.

HOST PADI BOYD: The first step in any scientific process is asking questions. And when we think about how to grow crops in space – there are a lot of questions to consider.

Gioia Massa

How do we grow the plants really well? How do we water the plants under different gravity levels? That’s a really big challenge actually. Figuring out what crops are going to meet the needs of different missions, and which crops are suitable for space. So we have to test a lot of different crops and see how they grow. And try to imagine how they’ll grow in space. Understanding the ecosystem and the humans, the plants, the microorganisms going on in these closed spacecraft. And then of course, there’s all the human factors: understanding how people and plants interact, how plants might be important for their psychological or behavioral health on these long missions? What activities they want to do with the plants and which plants we should grow for them at which specific times and how many? So there’s a lot of different factors that we think about. Trying to kind of answer these gaps and challenges is really our goal.

HOST PADI BOYD: This plant research lab is maybe not what you might picture when you think of a NASA laboratory. It’s a big area, full of all kinds of lush greenery and plant growing technology. And they study lots of kinds of plants – from fruits and vegetables to flowers and vines!

HOST PADI BOYD: Gioia, could you take us on a bit of a tour?

[Song: Blackthorn Instrumental by Blythe Joustra]

Gioia Massa

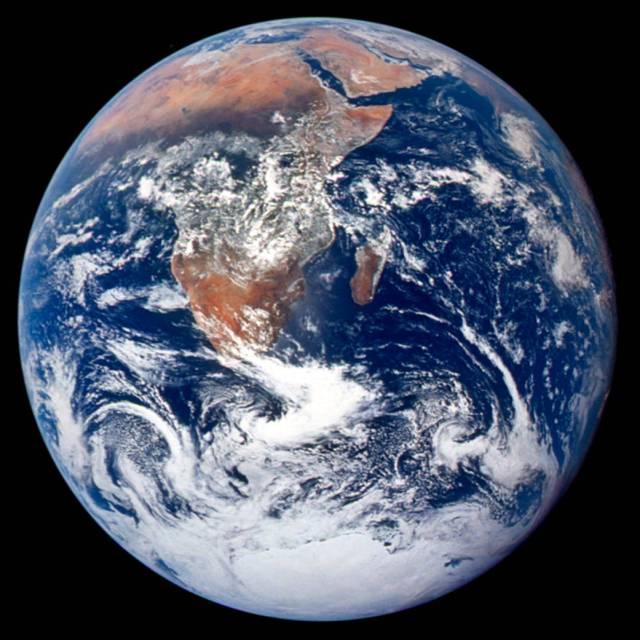

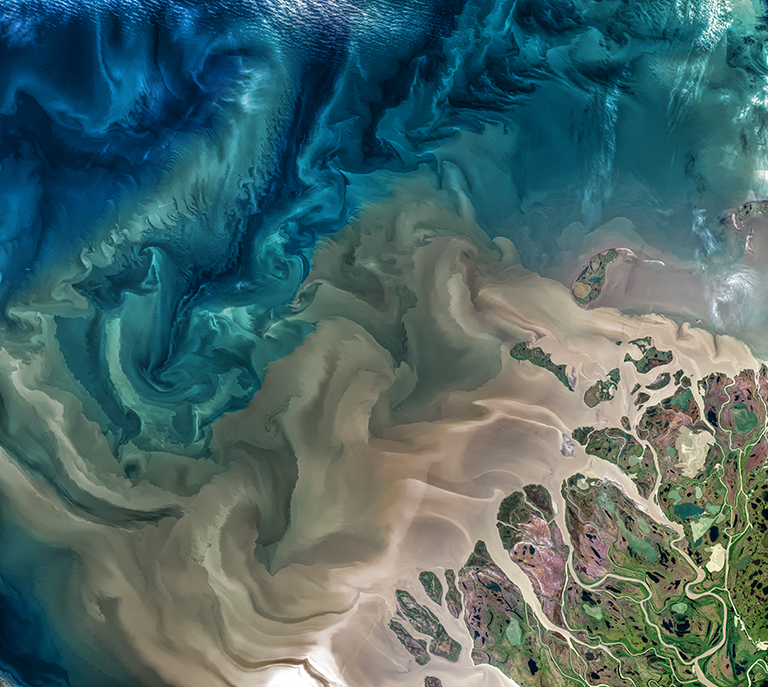

So our lab is in the Space Station Processing Facility, which is a pretty big building at Kennedy Space Center that was originally designed to test out all of the different parts of the space station. We now have a space crop production area, which consists of, kind of a big open area. And you go in through these really tall doors, I think they’re about 12 feet tall. And we have this actually beautiful artwork on the doors. There’s one with Earth and kind of a cornucopia and a rocket launching. The second one is the space station. The third door is the lunar surface with a depiction of a lunar surface greenhouse. And then the fourth door is a martian surface with a depiction of what a greenhouse on Mars may someday look like.

HOST PADI BOYD: The lab is broken up into sections, for different areas and timelines of experimentation. In order to learn about various growing factors, scientists have to be able to control various aspects of plant growth, including things like temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide, light, and more.

Gioia Massa

We have some very large controlled environment chambers, which look like really big coolers. We have an experiment with strawberries and we’re testing strawberries that grow from seed. And so you open the door of this chamber and this smell of just strawberries fills the air, it’s like you just wandered inside a carton of strawberries at the grocery store. We may have a chamber with herbs in there, similarly, where we’ll have, you know, basil or dill or mint. We’ve even tested some novel crops like kudzu and dandelion to see, could these be a good candidate for space?

Gioia Massa

We’ve done a lot of work with leafy green crops, mustards and lettuces and pak choi and kale and Chinese cabbage. We also do a lot of work with a crop called microgreens, which are baby plants, essentially, very, very small plants that are super nutritious, super flavorful. And we’ve tested a lot of tomatoes and peppers, and some of them grow really, really well.

Gioia Massa

We want plants that are compact and high yielding, some just get too leggy, you know, their branches just grow everywhere. And they’re just too big for the space environment. So we have to really grow them under our conditions of temperature, of high CO2, like we would find on the International Space Station, to see how they grow.

Ray Wheeler

We’ve been doing work in this area for oh gosh, 30 years or more. Twenty-five years ago, we focused on larger scale production systems with field crops, things like wheat and potatoes and soybeans. Now, I would say in the past 10 years, our focus has been more on supplemental food crops like salad crops.

[Song: Peonies Season Instrumental by Dury]

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s Ray Wheeler, a plant physiologist with the space crop team. Ray has been at NASA since 1988 and he’s studied a lot of plants. Some are better suited for life in space than others!

Ray Wheeler

We do have sort of a checklist you might say, of criteria. For example, we don’t want really tall plants in space, you don’t want to grow, say, an eight foot tall corn plant in space because you just don’t have that kind of room or volume. So we tend to think of shorter growing plants, even dwarf varieties of things like tomatoes and peppers. If they’re a salad or a supplemental crop, we target things like vitamins and antioxidants, things like that. You won’t get a lot of calories, maybe, or protein out of the lettuce plant, but you can get fresh food that you add to the diet. You want them to taste good. You want them to be appealing in appearance. So those things are important if you’re living in a confined space like a space station or you’re off to Mars, you want the astronauts and the crew to like the plants that they’re eating.

Ralph Fritsche

The standard thing you hear back is that they like things that are more spicy, more flavorful, because you kind of lose a little bit of that sensation.

HOST PADI BOYD: Living in space comes with a lot of challenges, and one of them is a lack of flavor. Astronauts have reported back that food is missing some of the punch we can find here on Earth. So scientists like Ralph think carefully about how to make their meals tastier.

[Song: Beyond Boundaries Instrumental by Heber Suffrin]

Ralph Fritsche

One of our most recent experiments was growing peppers in space. And the crew really liked them when they made tacos out of them. You’re looking for flavorful items, you’re looking for things that have some sensation.

Ralph Fritsche

Part of what we do in the validation process is doing screening to make sure that people even on the Earth think that these things that we grow are flavorful. We don’t want to bring something that’s highly nutritious, but nobody wants to eat! We look for flavors that are pleasing, some that are intense, so that we can kind of work with the crew’s palette in that spaceflight environment.

HOST PADI BOYD: But how do you grow plants in space? It’s not exactly like a garden – there isn’t a backyard to the International Space Station, after all. So engineers had to create special chambers for plants to thrive. Here’s Ray…

Ray Wheeler

You need a plant growth chamber. That’s a pretty broad, ambiguous term. But in essence, what it refers to is some containment or area where you can control the environment. You can provide light, and we typically use electric light sources like LEDs.

[Song: Driftwood Underscore by The Infinity Orchestra]

Ray Wheeler

You can manage the temperature, if it’s desirable to do that. You can manage the humidity. And then you have a system where you can allow the plant roots to establish. Maybe it’s in a solid media, maybe in the future, it’ll be in a hydroponic system for space. And then you can provide the water and the fertilizer and things that the plants need. So you sort of need all these basic, what are called controlled environment needs, that you have to meet.

HOST PADI BOYD: Plants need certain factors to grow – including water, light, carbon dioxide and nutrients like nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus. But without the regular patterns of day and night on Earth, Gioia and her team have found that space plants need extra attention, and can reap interesting benefits from manufactured sunlight.

Gioia Massa

Plants are incredibly responsive to light. And as lighting technology has advanced, we can now use the ability to give a very specific color pattern of lights to change how plants grow. You can use the colors of light to impact how much the plant grows, how fast it grows, how big it is, how nutritious it is, perhaps, how the flavor of the plant changes, and even how the plant responds to disease.

HOST PADI BOYD: The facilities in Kennedy’s Plant Research Lab are only half of the equation. The other major laboratory for studying these plants is onboard the International Space Station. So NASA’s plant biologists test as much as they can on the ground and then send their experiments on a rocket up to space! With limited room to transport cargo up to the astronauts, let alone grow it on station, it can be tricky deciding what to send.

Gioia Massa

The first thing you do is what’s called a science verification test. So that’s really testing the science in NASA’s hardware for the first time.

[Song: Trekking the World Underscore by Heber Suffrin]

Gioia Massa

See how the plants grow. How long should the experiment run for, you know, when are the tomatoes going to be ripe? Like if you’re doing a really early rehearsal for a play.

Gioia Massa

Then once you’ve answered all those questions, you develop crew procedures, and a very clear plan of what you want to do on spaceflight. And once you have that plan, and you have these procedures, we run the next step, which is called an experiment verification test. This is your full up dress rehearsal for flight, this is your practice of the play the day before opening with all your costumes on and everything.

Gioia Massa

Once you get all the way through that process, you get approval to go to flight. You basically build up two sets of whatever you need: one set launches to the space station, the other set stays on the ground. And when the astronauts have time to do your experiment on the space station, we start the same experiment on the ground. And we run it usually a day or two later, just so we can make sure we do everything that the astronauts did.

Gioia Massa

So we get data down directly from space station on the environment that the plants are in: the temperature, the humidity, everything that’s on space station, so that we can mimic the space station environment except for the gravity. At the very end, you’ll get samples back from space, you’ll get photos, all the data back. And you, as a scientist, can compare! We’ll look at the chemistry of the plants and see how much potassium is in the lettuce and how much calcium and iron and magnesium. We want to understand the food safety: was that lettuce different bacterially or fungally, than the lettuce that we’re growing on the ground? So those are the types of questions we ask and how we learn answers that can get us to the next steps for crop production.

HOST PADI BOYD: By controlling nearly everything except gravity and location, scientists like Gioia can zero in on the effects of space and microgravity on plant biology. That’s why they run the experiment twice – to try and keep everything else the same.

HOST PADI BOYD: And according to Ray, there are a couple major differences about growing the same plants on Earth and in space.

[Song; Chamomile Dew Instrumental by Hearson]

Ray Wheeler

There’s no gravitational orientation for plants in space. We do know that plants have evolved in a gravity environment just like humans. So the stems, the shoots as they’re called botanically, tend to grow up, they grow away from the direction of gravity, and roots tend to grow down. You don’t have that in space!

Ray Wheeler

Plants also respond to the direction of light. For example, if you put a plant on your windowsill, it kind of bends toward the window. That’s a light driven response. And so in the absence of gravity, we use light to orient the leaves and the stems. The roots, you just sort of contain, and you let them grow in the medium or however you’re containing them, because they don’t really have any clues. They will go where water is and so you can use that.

HOST PADI BOYD: There are other mysteries of space that are impacting plants, one’s we’re still trying to figure out solutions to!

Ray Wheeler

There’s more radiation in space. So you know, there’s subtle things like that you have to pay attention to.

HOST PADI BOYD: Right now all of the resources astronauts have on the space station were brought there from Earth. But there might be a time in the future when we return to the Moon or journey to Mars, and can use some of the natural resources there for food production. This is called, “In Situ” or “on the ground” gardening and it could be a possibility once we know more about these future farm sites.

Ray Wheeler

When you get to Mars, is there water ice? That would be a huge asset, if there were. We know Mars has carbon dioxide. Plants need carbon dioxide, so you have both carbon and oxygen in terms of elements, so those would be available. Can you get some nutrients and fertilizer? Maybe, from some of the surface rubble and regolith? Maybe. Probably, you’ll have to take a lot of that with you and sort of prime the system and maybe even with the water, you prime the system, but then you’ve run it in a highly closed mode where you’re recycling as much as you can. And so you create sort of a closed ecosystem.

Ray Wheeler

Mars and the Moon are really the near-term objectives. And Mars is sort of the ultimate for now. There’s interest in going to say some of the large moons of Jupiter like Europa. There’s very large moons around Jupiter and they might have water ice, but you’re going to have a lot less sunlight there.

HOST PADI BOYD: As a project manager, Ralph thinks about the long-term applications of these programs – how will crops be utilized or even necessary – as we plan our next explorations into space? And how can we create food systems that allow us to travel even further from our home planet?

[Song: Harvest Season Instrumental by Dury]

Ralph Fritsche

On a mission to Mars, we’re going to need something to supplement that crew system. Early missions to the Moon are just short in duration. We’re not going to be there long enough that we are going to have to worry about doing any kind of food production. But then when I start talking about putting out bases or outposts, now I’m looking at: how do I begin to cut the cord to Earth?

Ralph Fritsche

A big part of that will be food because food, and the logistics that food requires, the support, that’s a big part of the mass that I’m taking with me when I go places. So, we want to be able to cut down on that.

Ralph Fritsche

You really have to go knowing that you need to take care of yourself, resupply is something that will be very challenging, you’re not going to be able to go like we can now to the International Space Station. And so everything we do is to try to get to that point of: what, from the food system perspective, can we grow and produce locally so that we don’t have to rely on Earth quite so much as we do now.

HOST PADI BOYD: Even on Earth, we think a lot about the food we put in our bodies – the nutrients, the taste, and even the convenience. But one thing we might take for granted is how impactful our proximity to nature, to plants, to growing, thriving organisms helps our day-to-day life.

HOST PADI BOYD: Up in space, on station or on another planet, we won’t have that same connection to plants unless we create it.

[Song: High on Hope Instrumental by Bastock Rogers]

HOST PADI BOYD: And already, scientists like, Ralph, Ray, and Gioia have seen the emotional difference a little bit of space gardening can make for our astronauts living and working far from home.

Gioia Massa

A few years ago, we grew Zinnias in space. Not as a food crop, but as an example of what you would need for a flowering crop like a tomato or a pepper. We had a problem. Power was cut off. And when power came back on, the lights came back on, all the indicators came back on, what didn’t come back on were the fans. And we didn’t know that. So the plants were very stressed, and they were showing all this weird growth. And then we got fungus. We got a call at four in the morning: there’s something funny growing on the plants, and we finally figured it all out.

Gioia Massa

Scott Kelly was the astronaut at the time. He cleaned everything up, he reset the fans, and he took over watering on his schedule. And then the Zinnias that survived, and they didn’t all survive, some died from the fungus. But the ones that survived actually started to flower. And it just went from being this stressful, difficult, really upsetting experience to being just wonderful. He made a bouquet for the final harvest and he took these photos of this bouquet and he was so happy with the flowers. And they were so important to him for his long mission, you know, he talked about them quite a lot. Being a part of that just made me feel like, ‘Wow, this is really important’ and we’re just, we’re learning stuff every day. So I think it’s a great, great thing to do.

[Song: Curiosity Outro by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. This episode was written and produced by Christina Dana. Our executive producer is Katie Atkinson. The Curious Universe team includes Maddie Arnold and Micheala Sosby with support from Caroline Capone and Juliette Gudknecht.

HOST PADI BOYD: Our theme song was composed by Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of System Sounds.

HOST PADI BOYD: Special Thanks to Derrol Nail, Leejay Lockhart and the Kennedy Space Center team.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you’d like to see Scott Kelly’s floating Zinnias, we’ve linked the photos at NASA.GOV/CURIOUSUNIVERSE.

HOST PADI BOYD: And, remember, you can “follow” NASA’s Curious Universe in your favorite podcast app to get a notification each time we post a new episode.

Producer Christina Dana: What did you think about the movie ‘The Martian’ – is Matt Damon a good space farmer?

Ralph Fritsche

In a way, we thank him for getting the publicity that he did for the whole idea, but the how he went about it is just not something that would really work. Even from the standpoint of how potatoes would grow in that environment. They would be challenged to use Martian regolith or Martian soil and to grow like they did. There are chemical components of that material that just are not conducive to plant health and performance, let alone how you would fertilize them.

Ralph Fritsche

That movie came out and the book came out right about the time that Veggie was really starting to do things where we were growing plants and astronauts were beginning to consume it so it was one of those positive perfect storms where everything came together at the right time.