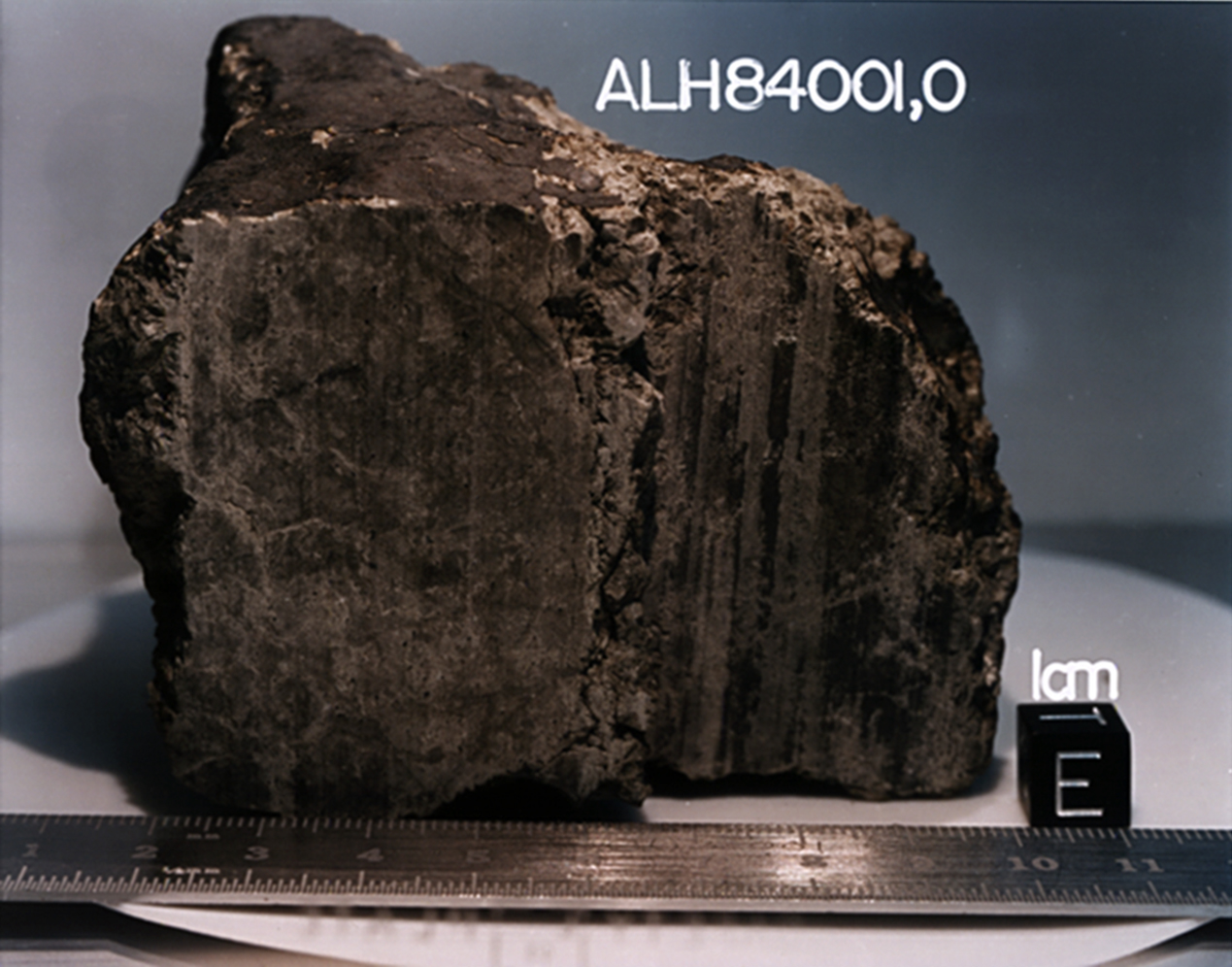

People have long wondered whether there is life beyond Earth, but it is only recently that scientists have been able to apply the tools of space exploration to go after this question. In 1996, the Allan Hills 84001 Meteorite shook the world as scientists debated whether it had tiny fossils inside of it that came from Mars. The consensus is that this rock does not contain Martian fossils, but the questions it raised energized many researchers. Today, the field of astrobiology is looking at how life arose on Earth and where else in the solar system and beyond life could exist. Beyond these scientific investigations, there are also philosophical questions one could ask. Would we be ready as a society for such a groundbreaking discovery? Astronomer and historian Steven Dick tells us there are many approaches to consider and many questions we should ask ourselves to get ready, in case extraterrestrial life is found.

Jim Green: Are we ready as a society to discuss what the next steps are, if we find life beyond Earth? Hi, I’m Jim Green, Chief Scientist at NASA. And this is Gravity Assist. On this season of Gravity Assist, we’re looking for life beyond Earth.

Jim Green: I’m here with Dr. Steven Dick, and he’s an astronomer and author and historian of science, most noted for his work in the field of astrobiology. Steven also has served as Chief Historian for NASA. And he’s been the Bloomberg Chair at the Library of Congress in astrobiology.

Jim Green: Today, we’re going to talk about the societal benefits, or not, about the discovery of life beyond Earth. If and when that happens. It’s all about changing our worldview. So, Steven, welcome to Gravity Assist.

Steven Dick: Glad to be here, Jim.

Jim Green: Well, you know, as I mentioned, you’ve been the NASA Chief Historian. And I’m sure many of our listeners don’t know that NASA even has a History Office. So what do historians at NASA really do?

Steven Dick: Ah, we do a lot of different things. We do a lot of book projects on various aspects of NASA history. We do a lot of conferences, on various aspects. And we do special projects that the administrator wants us to do. And we do our own research also. So it’s a it’s a very full job. We have a big archives, at NASA headquarters, and several archivists. So people are always calling in and asking questions about NASA history, whether it’s the media, or, or other people. There’s been a historian at NASA from the very beginning. So NASA realized that it was going to make history and it certainly has and will continue to make history.

Jim Green: Well, I see you’ve got the perfect two loves, and that is science and history. I mean, I’m really caught up in history. And when I think back about that early days of what we call the birth of astrobiology, of course, the 1996 announcement from the Allan Hills meteorite really stirred up a lot of controversy. Can you give us a little background on what that was all about?

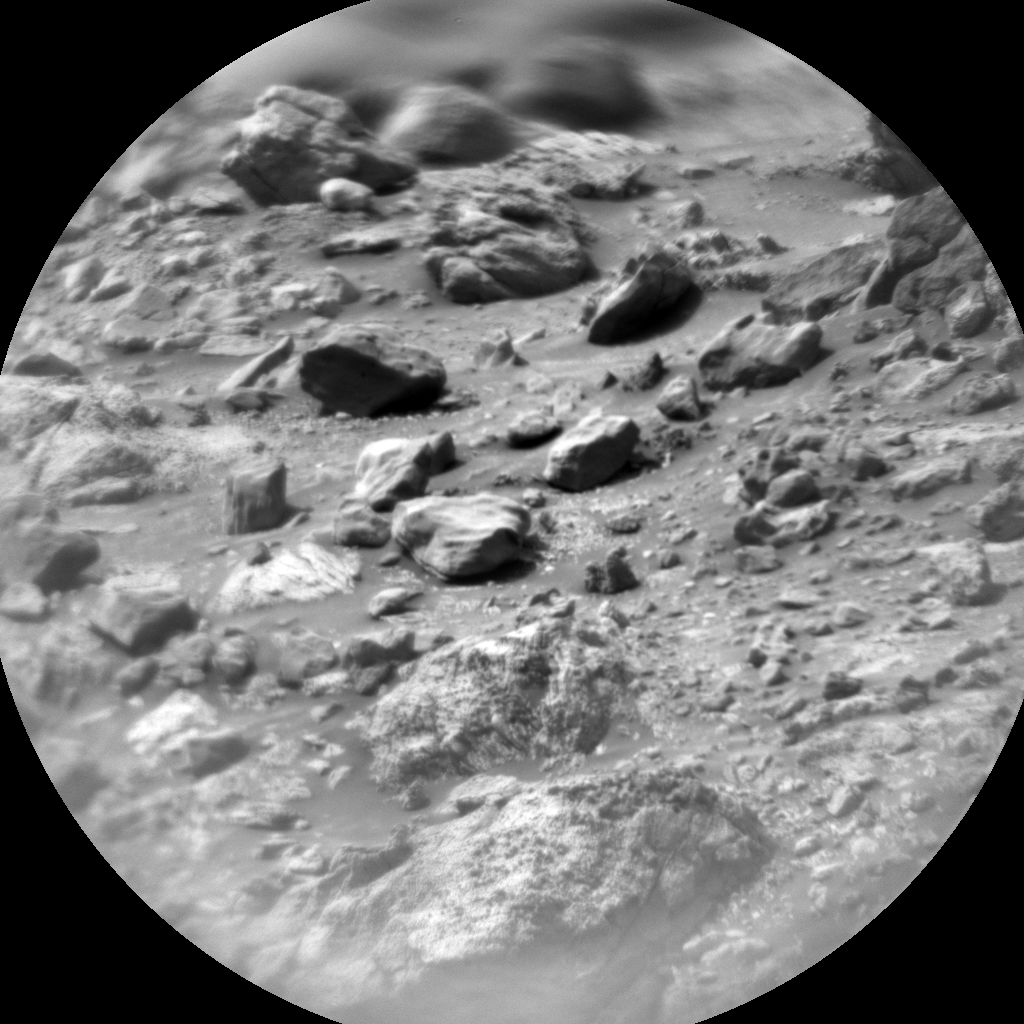

Steven Dick: Well, I write about that in my book. People are surprised that there are actually Mars rocks on the Earth. They do, though, the Earth intercepts rocks that have been spewed off of Mars. And usually they’re found in the Antarctic, and the Allan Hills, what’s called the Allan Hills 84001 meteorite, was found and recognized as a Martian meteorite.

Steven Dick: Scientists studied it very carefully especially down at Johnson Space Center. And then after three years of that kind of work, they made the announcement that they thought that there might be nanofossils, extremely small, fossilized life in that, in that Mars rock. So they made the announcement, I was on the beach. And my nephew came out and said they found life on Mars! And I said, “No.”

Steven Dick: But that was the beginning. That was the beginning of the controversy. And it was a very interesting press conference that was held at NASA Headquarters with the people who were making the claim, but also some skeptics.

Steven Dick: I use it as a kind of analogy to what might happen if we find extraterrestrial life, you know, in the future. You saw the, you know, the announcement and all the controversy that went on for weeks and months and, and years even. And you had congressional hearings, and you had symposia about this. And I myself was involved in one really interesting meeting with Vice President Gore, who called call the meeting to talk about the implications if this were true. And this was a small meeting with about 20 people. The NASA Administrator Dan Goldin was there and the director of Office of Management and Budget, and other people and… Stephen Jay Gould was there and Lynn Margulis, and some of the scientists who had made the announcement.

Steven Dick: Bill Moyers was there, there some theologians were there. So it was a real chance to talk about the implications. And this went on for two or three hours, going around the table and talking about what the implications might be. So that’s also the kind of thing that will happen in the future, I think at very high levels when we’re trying to figure out what the impact is going to be.

Jim Green: As you said, Mars meteorites do fall on the Earth and we go to the Antarctic, because blinding white sheets of ice are there. And if you see these dark spots, then they had to come from somewhere. And that’s typically from above. And at the time, the time the Allan Hills meteorite was found, we only had in our collection of 11 Mars meteorites that we could identify. Today we have about 170.

Steven Dick: Wow.

Jim Green: So, So indeed, we still have been collecting them. And it’s really been a wonderful cache. In the case of Allan Hills meteorite and looking at what looked like fossilized microbes, how did that resolve itself? And how did we determine that perhaps that wasn’t the case?

Steven Dick: Well, it’s a fascinating problem, both scientifically and philosophically, because you had three or four independent lines of evidence, in that, you know, leading to that conclusion that it might be fossil life. And the… some people said, well, if you have three or four weak lines of evidence that makes a strong argument, and other people said no, four weak arguments don’t make a strong argument. So they went back and forth over that. But in the end, it was just, you know, some of those lines of evidence just didn’t, didn’t pan out.

Steven Dick: And it goes back to, I think, what… something that Carl Sagan said were extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, right? And the evidence, there was evidence, but it just wasn’t extraordinary enough to make that claim, which is certainly an extraordinary claim. It’s possible things will change. You remember, the Viking experiments showed that there were no organic molecules, parts per billion on the surface of Mars. And so people would go, well, if there’s no organic molecules you can’t have life.

Steven Dick: Now, they’re thinking a little differently about it because of things called perchlorates. And, and all kinds of other things that maybe, maybe they did find life, or maybe they didn’t do the right experiments, you know, that gets back to the to the definition of life. Maybe they didn’t do the right experiments. And so that’s still open in the eyes of some people.

Jim Green: Yeah, indeed, Viking just scratched the surface in one location.

Steven Dick: That’s exactly right.

Jim Green: And Mars is huge, with a very complex geological history. And, you know, we’re finding by going to certain places, like what perseverance is going to do, land in an ancient Delta, where water spewed into the ancient ocean, leaving material from hundreds of miles. Wow! What, what are we going to find in those rocks? And we’re going to bring them back.

Steven Dick: Yeah, I can hardly wait for the results.

Jim Green: Me too.

Jim Green: You’ve written about the history of the way people think about life beyond Earth also. And so, are these all key moments that change the way people thought about the possibility of, of life beyond Earth? Or are there some other really important milestones in that area?

Steven Dick: Well, there have been at least a half a dozen cases where, you know, throughout history where people have thought that they might have discovered extraterrestrial life. You can go all the way back to Percival Lowell, you could go even further back than that to Kepler, and Galileo. Galileo in 1610, pointing his telescope to the Moon saw what looked like a perfectly round crater and Kepler, who was a very imaginative kind of guy said, “This must be artificial, built by the inhabitants of the Moon.”

Steven Dick: And then, of course, Percival Lowell of the late 19th century had this idea, which, based on observation, although very controversial observations, that there might be canals on Mars, and that these were the artifacts of a dying planet that the inhabitants were building canals and trying to get the water to where they, where they needed to be.

Steven Dick: But especially with the especially with the Mars rock, you started to see, you know, what the implications might be. It wasn’t… just not just the scientific facts, but the newspapers at the time, were filled with questions about what does this mean? You know, does this mean that there might be life all throughout the universe? And what would that mean for theology and philosophy and all kinds of different areas? So the idea of the impact of astrobiology on society also really picked up with this discovery of the Mars rock, even though in the end, the consensus now I think, is that those are not nanofossils, they’re probably, you know, not biogenic but it certainly precipitated a lot of a lot of different areas in in what we now know as astrobiology.

Jim Green:Yeah, I really love that history part of it. In fact, as you mentioned, Percival Lowell, really looking at Mars thinking, that there were canals with water being moved on this what may be a drier planet than then Earth, of course, really spurred the imagination and a few years after he, his first book came out, called the “Abode of life on Mars or something on that, or HG Wells wrote War of the Worlds.

Steven Dick: That’s right. And he knew about Percival Lowell.

Jim Green: Yeah. And so, you know, our science affects our culture. Just like in science fiction, we like to think of things that we write about the future and how we might be able to make things happen. So it works both ways.

Steven Dick: That’s right. I was a big science fiction fan when I was a youngster. So I think that when I was at NASA, I found that when I asked a lot of the scientists, they many of them were influenced by science fiction. And people, of course, like Carl Sagan was, so that’s right, it really fires the imagination to go out there and, and really see what you can find.

Jim Green: Well, you’ve said that intelligence is key to cultural evolution. What do you mean by that? What is the intelligence principle?

Steven Dick: Well, there’s this the Drake equation, I think a lot of people know about the Drake equation, which is Frank Drake in 1960, you know, was searching for, made the first search for signals from, from a possible extraterrestrial intelligence, and came up with the Drake equation, which was just the number of technological communicative civilizations in our galaxy. And it has all these factors in, and one of them has to do with a fraction of planets that might have intelligence on it.

Steven Dick: The intelligence principle to get to your question, is the idea that any society any civilization that can improve its intelligence will improve its intelligence. And so my claim is that extraterrestrials out there are highly likely to be post-biological, artificial intelligence. Because you’re, you know, the brains inside of our heads are limited. And with artificial intelligence you can do, you can do a lot more. And that would affect your SETI search. If you’re looking for post biologicals, rather than biologicals, like us. They’re not going to be like us.

Jim Green: Wow. So that really elevates you know, the possibilities of different kinds of life. So let’s say if we find life beyond Earth, what do you think will be the reaction by the public and what will happen next?

Steven Dick: Well, I wrote a whole book about that. So it’s hard for me to condense it all. But I usually put it in terms of, uh, worldviews I think our cosmological worldview would change, our philosophical and theological worldviews would change and our cultural worldviews would change.

Steven Dick: by cosmological, I mean, that we will, we will know that we no longer live in a physical universe, entirely physical universe, where we are the only kind of freak biology, the freak intelligence, that we live in what I call a biological universe. And that, you know, that that makes a big difference for, for our future, our sort of human destiny if you have a biological universe where we have to interact with intelligence.

Steven Dick: So there’s the cosmological aspect, then there’s the philosophical and theological aspect. If we engage with extraterrestrials, we will find out something about our own knowledge. Do they know the same things that we know? Do they see the universe the same way that we do? Do we have objective knowledge? Will our knowledge be the same as their knowledge? So that’s a huge question in philosophy. And when you go to theology, people have been arguing about this now for 500 years since Copernicus, but in the last few decades, it’s really, really picked up as the possibility of life as has increased, what the theological implications might be. And of course, there are all kinds of threads to that. And it depends on which theology you’re talking about. And every religion has its own questions that will arise in that case.

Jim Green: Yeah. Well, you know, a couple years ago, I was at a meeting, it turned out was in Europe, and a reporter asked me absolutely out of the blue, if we discovered life, is society ready for it? And it took me back and I said, “No, I don’t think so.” And that was the hot, that pretty much got the headlines everywhere. I was getting emails from all over the place, people saying, “Of course, we’re ready to, you know, to find life beyond Earth. What was I thinking, right?”

Steven Dick: I don’t think we’re ready.

Jim Green: I don’t think we’re ready, either.

Steven Dick: That’s one of the reasons that I think we need to prepare for discovery because you can have a better outcome if you’re if you’re prepared. One of the points I like to make is it very much depends on what the discovery scenario is, you know, it’s almost, it’s almost meaningless to say, what’s the impact of discovery life? Are you talking about microbial life, or intelligent life or intelligent life with a signal, or the signal that’s deciphered and what do they say? Those are all different scenarios that you’re having to consider when you’re talking about what’s the reaction going to be?

Jim Green: Well, you know, you’ve written also about ethical issues involving the discovery of extraterrestrial life. What kind of ethical questions should we be asking each other?

Steven Dick: Well, that’s, that spreads all the way from the spectrum of microbes to intelligence. If you find microbes on Mars, there’s immediately an ethical question: Is Mars for the Martians, even though they’re just microbes? Should we interfere? And you have scientists and ethicists on both sides of that question.

Steven Dick: And then, of course, when you get to intelligence, things are really multiplied, because you may have to actually interact with that intelligence. And, and, you know, it depends on what your theory of moral status is, we have enough trouble on the Earth with, you know, in terms of dealing with animals and that sort of thing. But the, the theory of moral status, if you have an anthropocentric theory of moral status, that’s probably not what you want to do if you’re talking about extraterrestrials, because everything would be focused on what’s best for us, not what’s best for them, and, and vice versa.

Steven Dick: Who knows what their ethics would be? And, you know, if you get a an example of some ethical questions, if you get a SETI signal, who answers? If it’s if there’s a decipherment? Who answers? Another question is, there’s this thing called METI, messaging extraterrestrial intelligence, where we actually send signals ourselves in a more proactive way, should people be doing that? And what should we be saying? And who speaks for Earth? All those kinds of ethical questions. Yeah, they’re very important. And I think that’s why we need to be talking about them now. And not just when that happens.

Jim Green: Wow, a lot to consider. Well, Steven, you know, we’re making all kinds of progress, you know, who knows what would happen? Maybe somebody tomorrow will announce, we have found life? What would be the first thing you would do?

Steven Dick: I would say, yay! I’ve spent a lot of my career on writing the history of this debate, and writing about what the impact might be. You know, you would have to go through several stages. Follow the evidence and have follow up research, we would live in a much more fascinating universe if we have other intelligence out there. I mean, it’s still possible that we are, you know, the only intelligence in the universe, but it seems very unlikely to me. And so, I think that, that’s one of the great unsolved questions in the, in the history of science, maybe the greatest unsolved question, if you’re looking at a very broad point of view.

Jim Green: Yeah, I agree with you entirely. You know, it’s that level of confidence that the whole scientific community’s got to get there. Right. And that takes time. No matter how you present the evidence, and what evidence you have available, it has to be interrogated. It has to hold up the scientific scrutiny. And that’s what makes it very fascinating.

Jim Green: Steven, I always like to ask my guests to tell me what was that event or person, place or thing that got them so excited about being the scientists they are today? And I call that event a gravity assist. So, Steven, what was your gravity assist?

Steven Dick: Well, I’m a, I’m a farm boy from Southern Indiana. So we had dark skies on that farm. And all you had to do is look up and see all those stars and wonder

Jim Green: Wow.

Steven Dick: I remember asking how many are there? And what? What do they like? And oh, and are there planets around those and that sort of thing. And, of course, I grew up during the time of the early space age, you know, when Alan Shepard and John Glenn and I followed that all very closely. And I also was in contact with NASA already. NASA used to put out something called NASA Facts. And I always waited for this big brown envelope to come with NASA facts about various things. And so I was very much, you know, I think the initial spark was that dark night sky. But then it was the space program itself. And these NASA Facts that kept coming in from, from NASA Headquarters and firing my imagination even more.

Jim Green: Wow, you know, that beckons back to also why you’re, you’re very much into history, because, indeed, with clear skies at night, our ancient ancestors looked and marveled at the sky, and looked at the wonders, even the Greeks looking at things that wander called planets. You know, and so indeed, that’s true inspiration.

Steven Dick: Let me say one more thing, and that is that when I was getting my bachelor’s degree in astronomy, I was at Indiana University, which is one of the few places that it also has a history and philosophy of science department. And so I would take courses over there because I always wondered, how do we get to know what we know when I’m learning about this astronomy stuff.

Steven Dick: And so I actually then after I got my bachelor’s in astrophysics, went to get my Ph.D. in history and philosophy of science. And the interesting thing is that I suggested doing a dissertation on the history of the extraterrestrial life debate. And they said, well, there’s two problems with that, in the history of science department. First of all, it has no history worth writing about. And it’s not science.

Jim Green: Wow.

Steven Dick:This was, well, this was back when, when exobiology was still somewhat, you know, a not, not so reputable, sort of taboo subject, so to do the history on something like that was considered very, you know, sort of far out. But I actually stuck with it. I had to switch advisors to do that. But I did a dissertation on the early history of the extraterrestrial life debate from Democritus, all the way up to Kant.

Jim Green: Wow.

Steven Dick: And yeah, and then, and that came out as a book by Cambridge University Press, way back in the early 1980s. And then somebody else picked up there and went up to Percival Lowell. And then I wrote the 20th century history with a book called The Biological Universe. So it turned out to be a pretty good, I think, dissertation, and I always tell graduate students to stick to your guns. Don’t let your dissertation advisor try to change your subject.

Jim Green: That’s right. Yeah. Well, Steven, thanks so much for joining me in discussing this fascinating topic.

Steven Dick: It’s been a lot of fun, Jim, thanks. It’s good to see you again.

Jim Green: Well, join me next time as we continue our journey to look for life beyond Earth. I’m Jim Green, and this is your Gravity Assist.

Credits:

Lead producer: Elizabeth Landau

Audio engineer: Manny Cooper