The Moon doesn’t have WiFi; neither does Mars. When future astronauts explore the surfaces of the Moon, Mars, or beyond, they’ll have big challenges communicating with Mission Control back on Earth. Darlene Lim at NASA Ames Research Center has been organizing expeditions on Earth that simulate science operations on other planetary bodies. Her team demonstrates how astronauts, scientists, and mission operations specialists can collaborate on expeditions, despite communication delays and location differences. She also discusses her role on VIPER, a rover that will explore ice deposits on the Moon and drill in shadowed craters colder than Pluto.

Jim Green:How does an astronaut know what to do when they are walking on the surface of the Moon or Mars?

Jim Green:Let’s talk to an expert who helps the astronauts do their job.

Jim Green:Hi, I’m Jim Green. And this is a new season of Gravity Assist. We’re going to explore the inside workings of NASA in making these fabulous missions happen.

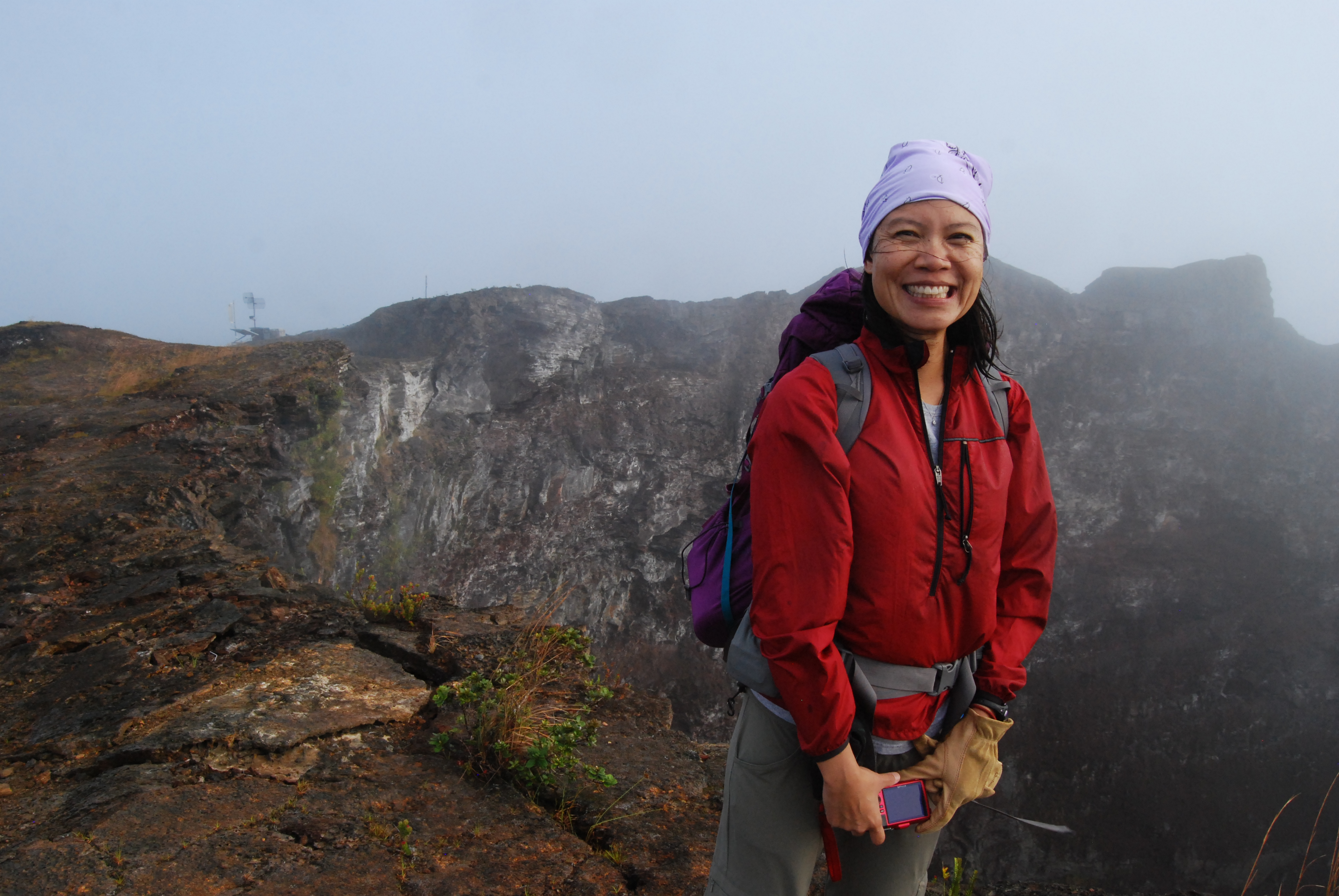

Jim Green:I’m here with Dr. Darlene Lim. Darlene is a NASA geobiologist and exobiologist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, out in Mountain View, California. Darlene works on preparing astronauts for scientific exploration of the Moon and Mars. Her expertise involves Mars human analog missions. And analogs are places that we go to here on Earth that are extreme, and have the physical attributes for the harsh environments that we’re going to send humans to in space. Welcome, Darlene, Gravity Assist.

Darlene Lim:Thank you so much for having me here. It’s such a joy, such a privilege. Thank you, Jim.

Jim Green:Oh, my pleasure. Well, we’re gonna have fun talking about analogs, you know, and you’ve, you’ve really done some fantastic work in using places here on Earth for these analogs that represent other worlds. How do you identify those sites here on Earth to go to?

Darlene Lim:Well, we start with the question, you know, what is it that we’re trying to answer? What are we interested in as a team? What’s driving us forward?

Darlene Lim:And then we’ll actually look for environments on Earth that are suitable in terms of allowing our teams to answer the particular questions that we’re interested in.

Darlene Lim:And then we look at the safety associated with going with to those regions, the accessibility of those regions, and then we look at the cost and so forth. So we’re very disciplined about how we select for the analog that we want to explore. And I think that’s a really important process to put forward because, you know, a lot of times the public will see us operating in fairly exotic, you know, extreme locations, but there, but we don’t just go to those areas because they look cool, because they’re on somebody’s bucket list. It’s because they help us answer very specific questions, research questions, as well as applied questions that will help us eventually get us to a place where we can design science teams that will support missions, human missions to the Moon, onwards, to Mars.

Jim Green:Well, you run a project called BASALT. Now, what does BASALT stand for? And what is its goal?

Darlene Lim:So BASALT, the acronym stands for Biologic Analog Science Associated with Lava Terrains.

Darlene Lim:I’ll tell you something funny. You know, the in-joke is that we select the project name, and then we, we put that out to our team, as we’re writing our proposals to say, okay, can somebody come up with a good acronym for BASALT?

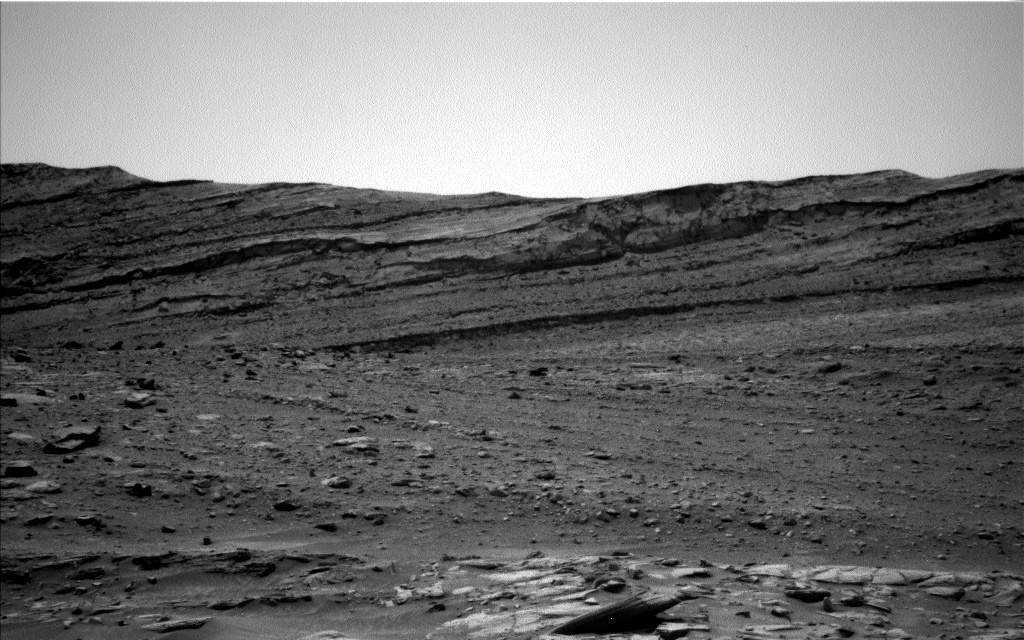

Darlene Lim:So the goal was to really have a merger, an integration of, you know, natural science, social science goals, as well as exploration goals. And we did so with the aim to answer the question: How do we support and enable scientific exploration during huan Mars missions? And so to do this, we took our team into two different analog sites, one in Idaho at Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, and one on the Big Island of Hawaii in the, in the Hawaii Volcano National Park. And what we did is we conducted scientific expeditions that were geared at answering astrobiologically relevant questions. But with a twist: We conducted all of those expeditions under simulated Mars mission conditions.

Darlene Lim:And we really wanted to do that so that we could figure out how best to enable science teams to interact with future astronauts that are going to be conducting science on our behalf, on humanity’s behalf.

Darlene Lim:Could we affect these EVAs, extravehicular activities, where the astronauts were out on the surface of Mars, exploring scientifically relevant areas? Could we affect those EVAs while they were happening? And the prevailing thought in the community was that no, in fact, because of the distance and the speed that it takes, or the time that it takes from a signal and a communication to go from the Earth to Mars, it’s too long, it’s anywhere from like 3 to 20 minutes one way, it’s too long to actually affect an EVA. While it’s happening.

Darlene Lim:Well, we actually wanted to test that. So we came into the process with a hypothesis that actually, if we did our jobs, right, if we attended to the devil in the details, if you will, we could set up support mechanisms, software, hardware capabilities, processes, architectures, that enabled science teams to actually interact with the astronauts while they were on EVA. And we found that this, you know, to cut to the punch line, this was possible. And if like, fact, that’s a major finding of our project, and in the process, you know, so much in terms of peer-reviewed scientific publications also came to, to, to fruition, even though the scientists were removed from the actual collection of the samples. And they enabled a small subset, you know, of people who were the astronauts, if you will, to collect and to do their science for them. So it was a really remarkable journey.

Jim Green:Now, there’s another project that you’ve led, and you mentioned it earlier. It’s called SUBSEA, I guess, right?

Darlene Lim:Right. You got it.

Jim Green:What does that stand for? And how did that project get started?

Darlene Lim:So it stands for Systematic Underwater Biogeochemical Science and Exploration Analog. How it got started is really through conversation between myself through partners that we have at NOAA, learning about the Ocean Exploration Trust, which is a not-for-profit organization that helps to manage one of the two federal exploration ships that we have in the United States, one of them, this one in particular, called the Nautilus, and starting to understand the infrastructure that they use to conduct ocean science.

Darlene Lim: What was fascinating to me, you know, in terms of like, how this particular project got shaped is that I started to hear about telepresence in the realm of how the oceanographers will have a small group of individuals go out to sea, but start to, you know, they always work to link a broader set of scientists on shore into the expedition.

Darlene Lim: And I’m like, “Hey, you know what, we, this is exactly what we’re trying to work towards in the scientific exploration realm when it comes to spaceflight. And what happened is, is, you know, we very fortunately found a wonderful group of scientists found partners in the Ocean Exploration Trust, as well as NOAA to come together write a proposal and eventually get it funded through NASA. We also had, you know, at, at our core, some natural science questions related to exploring hydrothermal systems that have analogous components to what we anticipate finding on Enceladus as well as Europa. So, so many pieces fell into place, so quickly, Jim, it was just, it was a joy to write the proposal, in fact, I know, it sounds a little weird. But it really was a joy to see it come together. And then, you know, of course, to go to sea a couple years in a row, and to see the work that’s coming out of that at this point in time.

Jim Green:Well, what’s it like to be on the boat when your, when your robot is exploring underwater?

Darlene Lim:It is intense, Jim. Like, it really is, we’re on four-hours-on, eight-hours-off shifts. So you’re, you know, any given moment in time, you’re either up or you’re trying to sleep or trying to grab a quick meal or, you know, exercise or catch up on work or whatever. And the whole time, the ship is holding station. So when we’re operating, we can be down, you know, a kilometer, a few kilometers down underwater, on a cable, on a tether. And at the end of it, as you explain it, there’s not one but two robots conducting our science and exploring these incredibly beautiful extreme areas deep in our, you know, on Earth’s oceans. And so the ship has to stay still.

Darlene Lim:We have to really be very disciplined about our communication. We cannot, you know, communicate via FaceTime with our families, because that draws on our bandwidth when you’re sitting in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. And we really have to be disciplined about how we run our lives so that we are awake, we’re alert when you’re actually on shift. So there’s a lot that’s going on, in any moment in time to enable this extreme, extremely difficult and complex exploration.

Jim Green: In the SUBSEA expeditions, what are you learning?

Darlene Lim:Ah, that’s such a great question. So actually, we’re at the point right now of our research program, where the publications are coming together, we have one that’s recently come out, that was led by Vincent Milesi, as well as Everett Shock out of Arizona State University. And what they put forward into the literature is a process for uptaking geochemical information as it comes in from the ship as we’re exploring the hydrothermal systems that we were exploring, and actually, you know, synthesizing that information and putting forward some decisioning around where they anticipate we should go next, that would best answer the questions at hand.

Darlene Lim:And there are several more that are coming out in terms of the microbial populations that we found associated with these hydrothermal the seamounts and hydrothermal systems. And there’s one as well, which examines the science operations, the integration of scientists at a remote setting in a distributed setting, and how that pertains to spaceflight missions. And, you know, both with robotic systems as well as human and robotic systems. So I think you’ll really start to see all those publications come out in the next 12 months or so.

Jim Green:Well, what’s your favorite story about SUBSEA expeditions?

Darlene Lim:From a research standpoint, it was watching the progression from our first year at sea in 2018 to 2019, when we use the first year to understand how the telepresence system was working, what components were, were being utilized by the oceanographic community. And then between, you know, the end of that particular expedition out to sea, where we went actually to the Lōʻihi Seamount, which is just off the coast of the Big Island of Hawaii.

Darlene Lim:From that moment, you know, forward for the next year forward, there was a lot of research a lot of data processing that went into place to create new infrastructure for the 2019 expedition when we went out to a place called Gorda Ridge, which is just off the coast of where California and Oregon meet. And what happened is that we created a process for a science team to be co-located at the University of Rhode Island where they have something called the Inner Space Center, which is basically a mission control. And we created software as well as process, you know, capabilities that enable the science team to really be interactive, in a manner which was, which was very much akin to what we anticipate certain exploration conditions to be like going back to the Moon, moving on to Mars, with robotic and human elements, you know, in play.

Darlene Lim:But then from a personal standpoint, I think, when I would have to get up right on the cusp of where the sun was coming up, and sleepily come out, get my coffee, climb up this couple sets of stairs to go to the mission deck, Mission Control deck on the ship. And I would see the sun just kind of come up over the Pacific. And there were always those moments where I was there by myself, and it was so beautiful. And just very, I felt very grateful in that moment to be in the line of work that I’m in, to have had all of the support mechanisms in my life in place, so I could be there in that very moment in time. And that was extremely special for me and will always, you know, be embedded in my fiber.

Jim Green:Wow. Yeah, I understand. Those. Those moments indeed are so precious.

Jim Green:So when you’re out in the field and things don’t work, right, I’m sure you get frustrated. What happens when that occurs and how do you overcome it?

Darlene Lim:That is such a great question because every day something goes wrong. And the only thing that we can be certain about when we plan for these missions is that something will go wrong. And so you can think about every single contingency possible. But inevitably, you know, there will be something that pops up that is a little bit different than somebody had thought about. So I think the key thing is to in the pre-expedition season, to build camaraderie, collegiality, and trust between the humans that are involved with the mission. That, it sounds like a very simple thing to do. But it really is difficult when you have a lot of people coming together for the first time from different disciplines. And, but if you if that trust is built from the get-go, then when these very difficult moments pop up, then you know, everybody trusts their colleagues to come with the right answers at the right moment and solve them.

Darlene Lim: Now, there have been other circumstances where weather has come in just sudden inclement weather, and affected our communications, architecture and so forth, and you know, we’ve had to, of course, fix things on the fly. Our engineers are very capable, very ruggedized human beings. But we also had process[es] in place to say: Everybody’s got to stand down, everybody’s got to head back to these safe areas, because number one is the safety of our humans out in the field. And I think that is very high fidelity as well, for when we send humans back to the Moon and Mars. Their safety comes first, above and beyond anything else.

Jim Green:Well, I know you’re involved in another really exciting mission to the Moon, and it’s called VIPER. So what does VIPER stand for? And what is it supposed to learn?

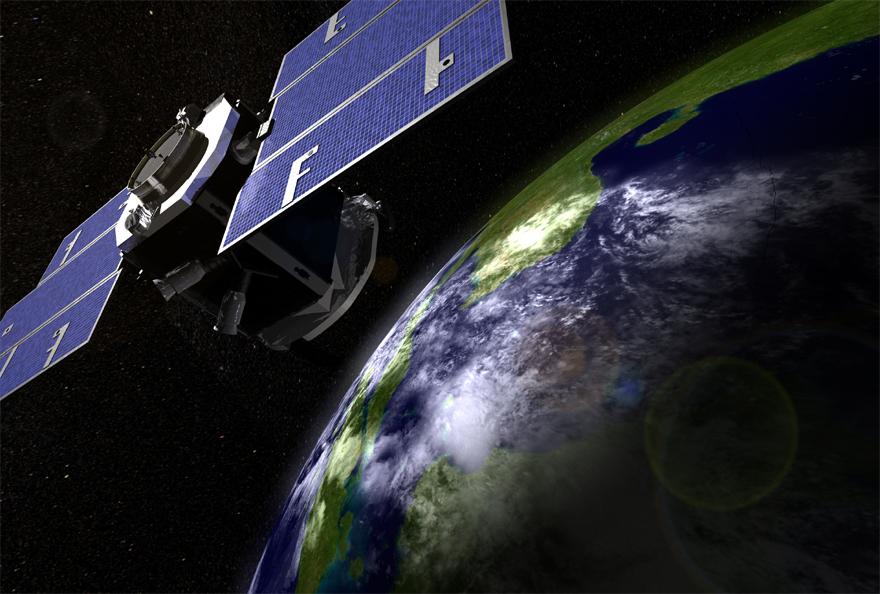

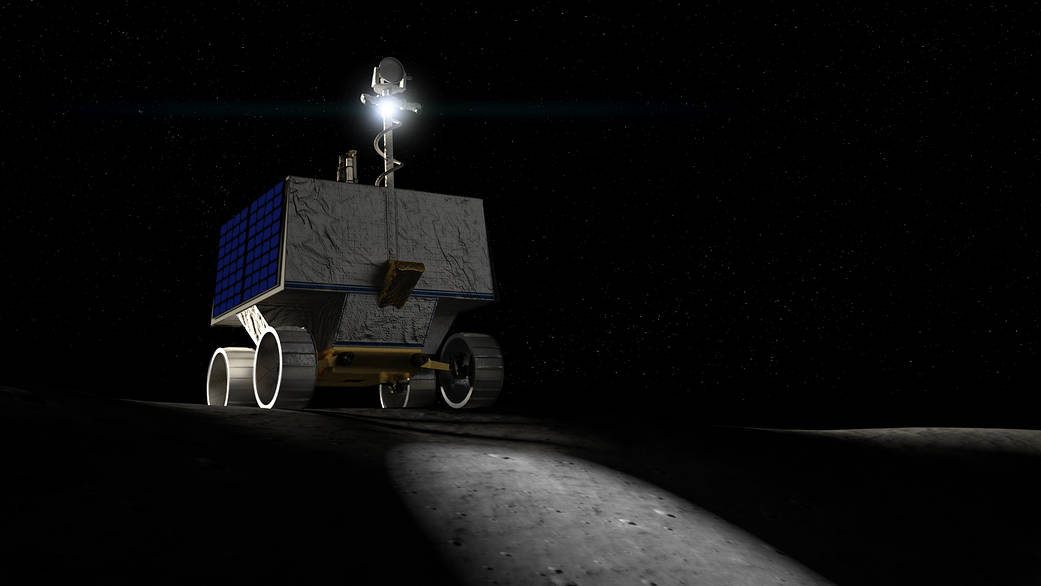

Darlene Lim:So VIPER stands for Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, or VIPER. And, you know, as it as it is written out, it’s a mobile robot, it’s going to go to the south pole of the Moon. And it’s going to prospect it’s going to explore it’s very exciting. It is looking for, for volatiles, it’s looking for water resources, that we can finally you know, really map extensively and then understand, characterize, because this has implications for, you know, near-term missions back to the Moon, as well as human missions back to the Moon, that we’re anticipating as well coming online.

Darlene Lim:And so it’s very exciting to be a part of this really groundbreaking project. And my role in it is actually to help lead the science operations as well as the science integration with the broader engineering efforts. And what this is, is, you know, really a labor of love for me, because all of the many years, the 20 years of working in analogs, and you know, really starting to take that knowledge, which, you know, as I mentioned, has been focused on understanding how to integrate science and science decisioning into any sort of exploration endeavor is now you know, in, I’m now in a position where I get to apply that knowledge firsthand to a mission a flight mission. And that is, you know, a dream come true from any which way you look at it.

Darlene Lim:But what’s cool about VIPER and what we have to innovate on is having a science team which is going to be able to make near-real-time decisions that will affect, for example, where we select a drill site. So we’re going to be drilling with this, with this rover as well. And, and the science team will actually have the capability of providing feedback to that process of where we actually drill. And, so because of the capability for us to receive information from the Moon fairly quickly, we’re actually going to be receiving quite a lot of data that the science team has to synthesize, has to analyze and then has to, you know, make decisions on and push forward to the Mission Operations Center in a way which is you know, quickly can be quickly uptaken by those that have to drive the rover and make some really important tactical decisions.

Jim Green:Well, you know, Viper as a rover on the Moon, it’s going to the south pole. And it’s going to be in areas where the Sun doesn’t shine, what we call permanently shadowed areas, is Viper designed to go in, get a drill full of material and analyze it and come back out?

Darlene Lim:Well, that’s, yes, exactly. And it is, it’s, I’m so happy you brought it up, because it really is non, nontrivial, right? I mean, this is a very difficult thing to go into an area where you will be in a very cold area, you will be without light. And so what’s fascinating about the way that the VIPER mission is being run, is that we are, you know, going to be nominally operating for three lunar days. So, you know, a lunar day is about 28 days. But within each of those lunar days, there, there are going to be about two weeks where we don’t actually have a line of sight to the rover, that will enable us to conduct near-real time activities. And so there’s like a two weeks on, kind of, two weeks off cadence that we’re going to be experiencing as a science team. And indeed, as you mentioned, there are moments where the where the rover is going to dip into these permanently shadowed regions, very difficult operational environments to work in.

Jim Green:Well, these areas on the Moon, where the sun doesn’t get to, we call the permanently shadowed areas, and they are some of the coldest places in the solar system. In fact, they are colder than the surface of Pluto. So being able to get in, get your drill going, get a sample, analyze it, look at it, and then get back out, is really going to be difficult to do. So I really appreciate how hard this is.

Jim Green:Well, Darlene, I always like to ask my guests to tell me what was that event or person, place or thing that got them so excited about being the scientists they are today? I call that event a gravity assist. So Darlene, what was your gravity assist?

Darlene Lim:Well, I am so grateful for you to ask this question. Because I tell you, it’s taken a village to get me to where I am. And I will answer your question with two answers. First, it’s people, many people there are the colleagues that have believed in me, there are my parents who have showed me what hard work is, gave me an appreciation for the natural world. They were immigrants to Canada, and they really wanted to embrace their new country. And we spent a lot of time camping and fishing and so forth, that gave me such a love of the natural world and you know, imbued me to this day with that love. And my mom, you know, my mom, she, she, came to help care for my kids, when they were young, I have two children, so that I could go into the field, so that there was that possibility, and I couldn’t have done anything without her. She was a huge gravity assist in my life. There’s my husband, who’s a true partner in every sense of the word.

Darlene Lim:And then there are my kids who inspire me to be better to work smarter, to be more focused every single day. There is not a spare moment because I want to be present for them too. So as a collective, I see all of these people as being so intrinsically part of the gravity assist.

Darlene Lim:And then the second thing I want to mention is that event-wise, every single failure that I have been through in my life, every single anxiety, moment of difficulty, I wouldn’t be here in this, you know, place speaking to you if it wasn’t for all of those failures that we don’t see captured in our CVs that we don’t see captured in, in even these types of conversations, but they’re there. And they’ve helped me understand how to be better at my job, how to be more thoughtful, how to be more inclusive, how to, you know, get through difficult things and know that it’ll be okay on the other end. And that’s such a big part of learning to work with other people.

Jim Green:Well, Darlene, thank you so much for joining me in discussing these fantastic things that you do to help make this agency successful.

Darlene Lim:Thank you so much for having me on this wonderful program, Jim. I really appreciate it.

Jim Green:My pleasure. Join me next time as we continue our journey to look under the hood at NASA and see how we do what we do. I’m Jim Green, and this is your gravity assist.

Credits

Lead producer: Elizabeth Landau

Audio engineer: Manny Cooper