Award-winning journalist, space historian and author Andrew Chaikin discusses the Apollo Program, almost 50 years after the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

Andrew Chaikin: When Neil and Buzz stepped onto the Moon. I was sitting in my parents’ bedroom with them, watching it on the old black and white Zenith. It’s just indelible.

Apollo, to me, is an adventure that deserves telling and retelling again and again.

It’s just one of the great gifts to history that humanity has ever had.

Deana Nunley (Host): You’re listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps – a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast featuring interviews and stories, tapping into project experiences in order to unravel lessons learned, identify best practices and discover novel ideas. I’m Deana Nunley.

It’s been almost 50 years since the Apollo 11 lunar landing. Award-winning journalist and space historian Andrew Chaikin joins us today to discuss Apollo legacies and lessons learned. He’s the author of “A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts,” the 1994 book that was later made into the Emmy-winning HBO miniseries, “From the Earth to the Moon.”

Andrew, thank you for being our guest on the podcast.

Chaikin: My pleasure.

Host: When you consider the greatest achievements in history, where does Apollo rank?

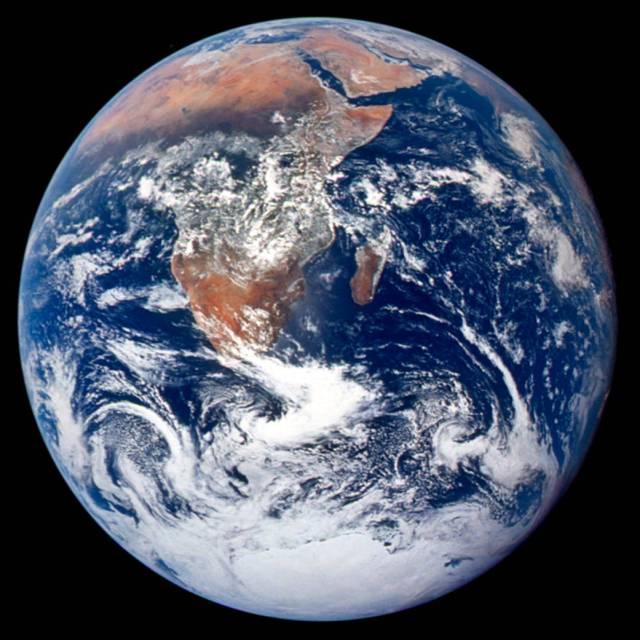

Chaikin: Well, Apollo certainly has to be among the greatest achievements in human history because it really stands on a level that is beyond the history of any one nation or the history of any one group on the Earth. It really is an achievement, a milestone on the level of the human species. I mean we’re talking about the first time that humans left the planet of their origin and journeyed to another world. So, that’s monumental, no matter how you think about it.

Then as you delve into Apollo the way I have, you see what a magnificent achievement it was on so many different levels — on a human collaboration level, on a scientific level. All of these things just place Apollo right up there at the pinnacle of what humans are capable of doing.

Host: What do you see as the primary enduring legacies of Apollo?

Chaikin: Well, to me, there are three main legacies of Apollo that continue to endure 50 years later, and I think will endure as long as there are human beings, really. The first is the human collaboration. If you think about it, Apollo employed 400,000 people at its height, at NASA and its contractors, just an enormous number of people to kind of marshal and get going in the same direction, and focus their efforts on all of the daunting problems of sending humans away from the Earth and to the Moon.

That was a phenomenal exercise. It’s almost as if the government funded an experiment in how to do hard things with extremely large groups of people. We certainly stumbled along the way. The Apollo 1 fire that killed three astronauts on the launch pad was a terrible tragedy, but NASA recovered from that brilliantly, and the execution of the program from that point on is really quite mind-boggling in how successful it was, how flawless it was, for the most part.

I mean nobody would have imagined that Apollo 11 would actually be the first landing attempt. There were so many chances for things to go wrong on the previous missions. But there we are. We get to July of 1969 and, lo and behold, every previous mission has gone just about flawlessly, and Apollo 11 did, too, not that there weren’t close calls, of course.

So, I think the first, really maybe the greatest legacy of Apollo is this human collaboration piece, which really stems from what I would call a success culture of spaceflight that was created at NASA.

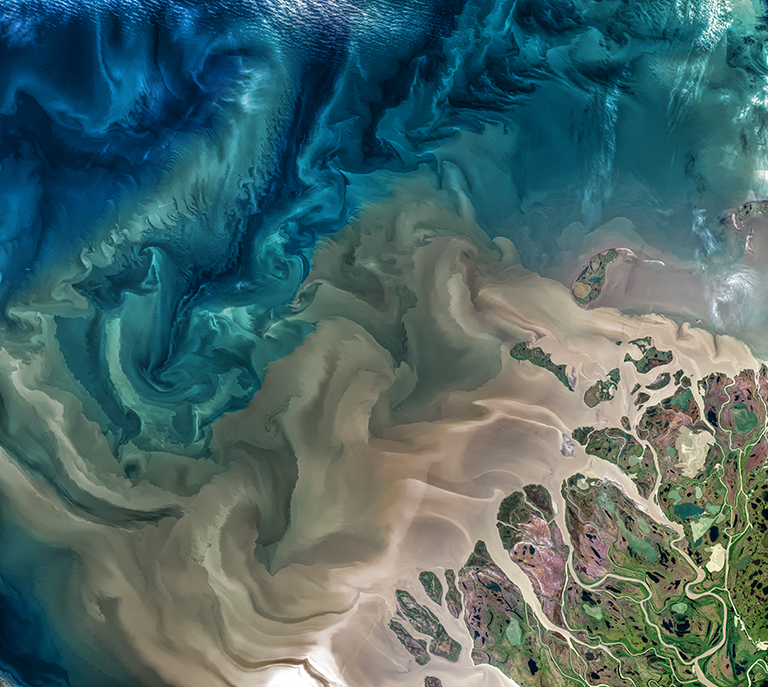

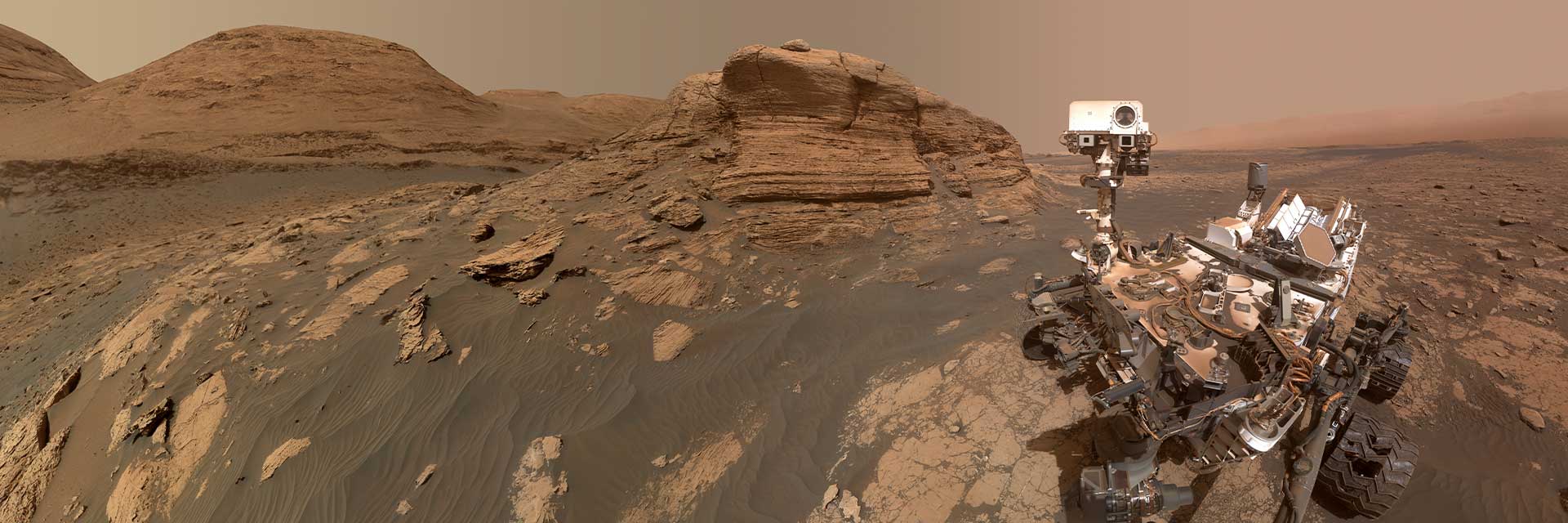

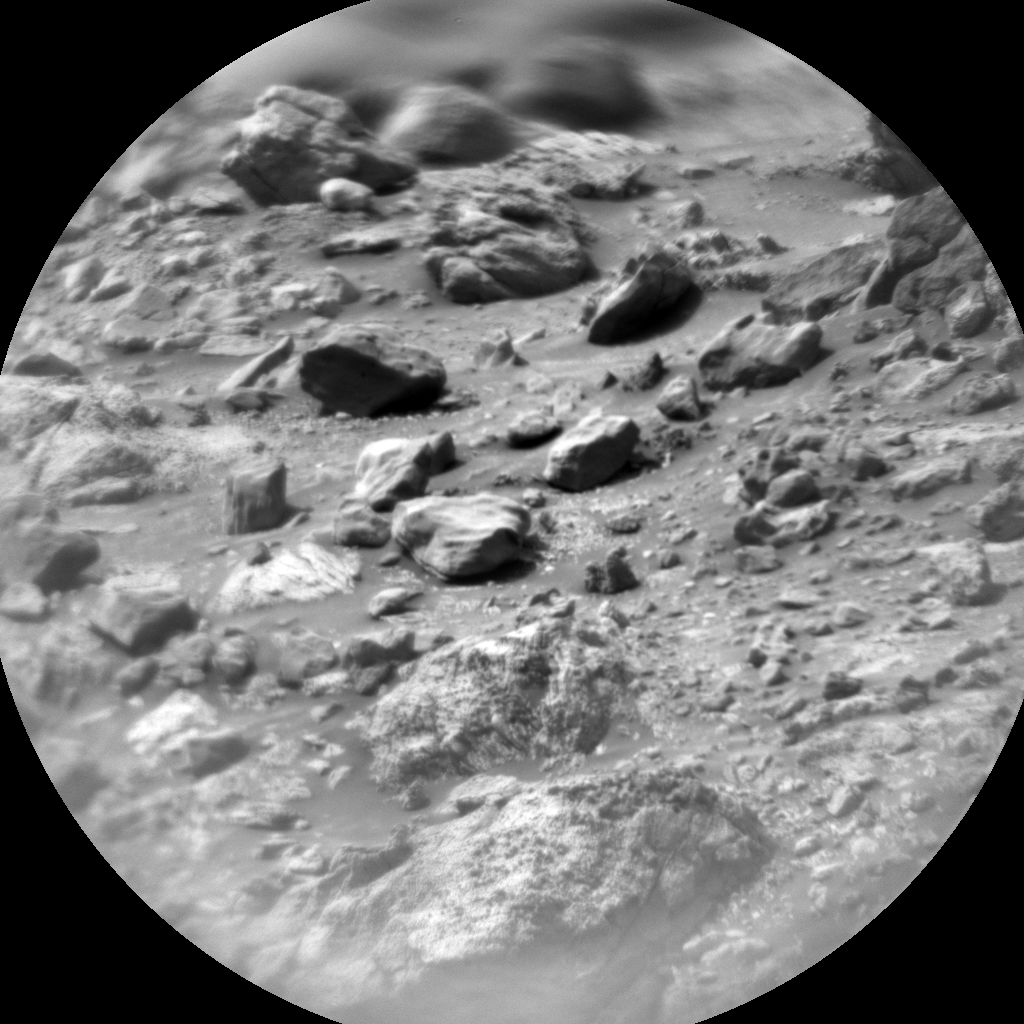

Number two, I would say is the scientific legacy, the fact that the Moon really became – because of the Apollo samples, the Moon really has become the Rosetta Stone for deciphering the earliest history of the solar system. It really is the place that preserves most clearly the earliest chapters in solar system history, and we got so much from the Apollo samples that we then used to figure out what happened to the early Earth and to planets like Mars and Mercury and Venus and so on. So that’s number two.

Number three I would say is the change in awareness that we got from going out to the Moon and looking back at the Earth from almost a quarter of a million miles away, and the profound awareness that we got from that, that the Earth is really quite precious and deserves to be protected. It’s, as Jim Lovell called it, the oasis in the vastness of space. So, to me, those are three enormous legacies, which I think will continue to endure.

Host: When we look at the Apollo program, what was the mindset of the NASA workforce that led to success?

Chaikin: First and foremost, I would say it was an absolute devotion to the physics of the problem. In other words, the physics doesn’t lie. You cannot get around physics. So, your engineering has to reflect that. So, it was a culture that was devoted to engineering truth. That rose above any considerations of ego. You had to kind of check your ego at the door to be successful in this business. Not to say that there weren’t some very strong personalities. There were. There were lots of knock-down, drag-out discussions, arguments about engineering questions, but everybody understood it wasn’t personal. So that would be one of the elements of the success culture.

Another element of this culture is trust. One of the Apollo flight directors, Gerry Griffin, said to me recently that, in his mind, one of the reasons Apollo succeeded was that decisions were made at the lowest level possible rather than the highest. That meant that people trusted each other, upwards and downwards. The managers had inherent faith and trust in the people they had hired and the people that were working under them.

So, for example, if you look at mission control, look at the people who were in mission control during Apollo. The average age was mid-20s. I mean these were very young folks, who were handed enormous responsibility, and they recognized that and they still talk about how amazing that was. Glynn Lunney, one of the Apollo flight directors, said to me, “We were in awe of what our leadership team allowed us to do.” So that was another element.

Then I would say we have to talk about the ability to learn from mistakes, the ability to discuss mistakes openly. Chris Kraft has made this point, that when they made a mistake they talked about it when it happened. They talked about it openly and they talked about how to fix it, and they all understood that failure is the best teacher.

Not to take anything away from Gene Kranz, who has been associated with motto, “Failure is not an option,” although he never actually said that. He didn’t have to say it because everybody knew it. When human lives are at stake, as they were with Apollo 13, yes, failure is not an option. But when you are in development, you must fail in order to succeed and you must learn from those failures. I could go on and on about this. I mean this is a very deep and rich subject, but I think if I were going to take a first cut, that would be it.

Host: And, so, when we look at the NASA of the Apollo days, and then we look at NASA of today, what are some of the differences and what are some of the similarities between the two?

Chaikin: Well, I’m afraid the differences have existed for a very long time. Right after Apollo succeeded with Apollo 11, the very next year, 1970, was the time frame when NASA was really feeling that it was almost in a survival situation. The budget had already declined drastically since the peak of the Apollo years. Now, this is understandable if you think about the fact that Apollo was created as a battle in the Cold War. Kennedy’s goal was to show the world the strength of our free society by putting humans on the Moon, and winning the battle for hearts and minds that was at the heart of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

So, Apollo was funded like a war. So, it’s not surprising, if you consider that, that the funding didn’t stay at that wartime equivalent level. It did come down. It came down even before we reached the Moon, but by 1970, NASA was feeling the pinch.

I think this is something that NASA has had to live with, that we can never go back to Apollo. We can never go back to the 1960s. And every program that has come up since Apollo has had to deal with very real financial constraints and, by the way, political constraints. There is an influence of politics that even has come to affect the engineering choices that NASA makes. One of the shuttle veterans called it political systems engineering. He said, “It’s a fact. We have to live with it.”

So, I think, when I look at NASA today versus NASA in Apollo, I would say those are some of the biggest differences, that NASA does not enjoy the same freedom, both economically and politically that it had during Apollo. Of course, NASA has always done what the executive branch has told it to do. NASA is an executive agency, but you see what I mean. It’s like we didn’t have Congress looking over NASA’s shoulder during Apollo and dictating engineering requirements.

So, I think those are some of the biggest hurdles today. NASA has a lot on its plate, keeping the International Space Station going, the SLS Orion program, Commercial Crew. All of these things cost time, money, energy. Then to add on to that, the return to the Moon brings yet another challenge to NASA’s plate. So, I think it’s a very daunting situation, and I hope that it goes well.

Host: In terms of challenges as NASA prepares to send the first woman and the next man to the surface of the Moon by 2024, what are you seeing as the biggest challenges?

Chaikin: I’m very much focused on the human piece of the equation. As a historian, for the last eight years or so at the request of NASA, I have been delving into success and failure through the lens of human behavior. What I’ve discovered is that even though the engineering is extremely challenging – I would never minimize that – the rocket science is very tough, but it turns out that it’s not the toughest piece. It’s not the rocket science that trips you up. It’s the human behavior piece.

So, what I’ve done is gone back to Apollo and looked at the behaviors that got us to the Moon, and the behaviors that got them off-track and led to the Apollo fire, and then again, the behaviors, the attitudes, beliefs and assumptions that allowed them to recover and ultimately succeed. It all comes down to mindset.

I feel very strongly that one of the biggest challenges is to get people who are not really focused on human behavior – I mean engineers, after all, that is not their comfort zone. But the challenge is to get them to focus on it and to really make it part of what we talk about on a day-to-day basis because, otherwise, we’re vulnerable to patterns of behavior that are sort of hardwired into us.

I’ll just give you one example. In my presentation of success and failure, one of the things that I talk about is false perception of risk. That’s something that has come up again and again in NASA’s history. It’s basically when you have a behavior in your system that isn’t what you expected. It isn’t what you thought you were designing, but the problem comes up and yet it doesn’t cause a catastrophic failure. So, you keep flying.

Think, for example of the O-rings in the shuttle solid rocket boosters that eventually led to the Challenger accident. People knew about the problems, but they said, “Hey, we’re okay. It doesn’t seem to be biting us. We’re okay.” The little voice in your head says, “It hasn’t bitten us yet, so we must be okay.” And you keep flying, and you don’t even see how close you are to the edge of the cliff because you’re under pressure. You’re under political pressure to keep flying. You’re under schedule pressure. You’re under cost pressure. And those pressures literally distort our perception of where we are in the real world.

So, that’s something that we should be talking about on a day-to-day basis. Hey, are we falling into the trap of false perception of risk because of these pressures? I would like to see that become part of the process that we do in order to be successful, as part of a whole framework around human behavior that I’ve been trying to spread at NASA and elsewhere.

Host: What are some of the other key lessons learned from Apollo that the NASA technical workforce needs to be reminded of as we get ready to return to the Moon?

Chaikin: Well, I think, again, nature doesn’t lie. Physics doesn’t lie. If you start to see signs that things are not going the way you expected, you better pay attention to that. You better make sure you don’t get rushed into flying because of schedule pressure and political pressure, and minimize a problem that’s on your radar screen, because you can’t escape the realities of the physics. The engineering has to be reality-based.

So that to me is one of the great lessons of Apollo, that when they tried to go too fast, as they did before the fire, they paid the price. To me, that fire was a wakeup call to NASA. It was a message to NASA saying, “You guys need to step up to a new level of rigor if you want to pull this off.” And they got that message and they did step up. That’s why, after the fire, they were able to go from tragedy in January of 1967 to triumph in July of 1969.

Host: You mentioned earlier about patterns of behavior. I want to talk about patterns in terms of timing. I believe you’ve mentioned intervals between accidents. When you look at the time between accidents, where are we now and how does NASA need to look at that?

Chaikin: I think the main thing that I want to say is if you look at the history of NASA, you see three major human spaceflight accidents: the Apollo fire in January of 1967, and then 19 years later, almost to the day, it’s really 19 years and one day after the Apollo fire, the Challenger accident happened, and 17 years and, what, three or four or five days after that was the Columbia accident. So, what this is telling us is that human awareness, conscious awareness has a shelf life, that we are always in danger of forgetting the lessons of the last accident. We are always in danger of falling back into patterns of behavior that got us in trouble before.

So, we have to be a little bit paranoid, actually. One of my heroes, Gentry Lee, an engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who I first met when I was a college intern on the Viking Mars landing, he’s now one of the senior engineers at JPL, and he says, “You have to bring to the work proper paranoia,” which means being scared to death that it won’t work. You have to have that to succeed.

So, if you look at the periodicity of that, the meantime between accidents, it’s something like 17, 18 years. So, we’re just about due if you go by that periodicity. It doesn’t mean we will have an accident a couple years from now or three years from now, but we should be aware of the fact that the more time that goes on, the more turnover there is in the workforce, the harder it is to preserve the lessons that we’ve learned at such great cost.

We have to pay attention to those lessons and we have to talk about them. It has to be part of the way we do business. It’s not enough to just put up a database. As much as I really applaud the lessons learned databases and so forth, it’s not enough to just put up a database with case studies. We have to be talking about the lessons of the past, the mistakes of our predecessors and how they recovered from them if we want to be successful.

Host: From your perspective and talking with a lot of people across NASA, how do you think the agency is doing in that regard?

Chaikin: I think it’s mixed. I think that there is a lot of recognition of the importance of lessons learned, and that’s become a very often-heard phrase at NASA, but in terms of actually living by them, that’s much harder. People who are under pressure, it’s very, very hard to resist those pressures, political pressure, cost pressure, schedule pressure. It’s very hard to stand up to those pressures and do what you know in calmer moments is the right thing.

It’s a real challenge and it pushes us out of our comfort zone. I think one of the lessons of spaceflight is that we can’t afford to live in our comfort zone. For example, one of the things that engineers tend to want to do is to just look at the piece of the system that they’re directly involved in. They say, “Let me stay in my swim lane and I’ll meet you at the end.”

We don’t have that luxury in spaceflight because it’s such a complex system. Everything is so interrelated, and tiny little changes over in one area can have unexpected consequences in another area. I can give you so many examples of that.

Do you know why the Apollo 13 accident happened, the oxygen tank that exploded on the Command Service Module? It happened because of a seemingly minor change in voltage in the operating system that they used on the launch pad years before the mission, and that change in voltage was never communicated to the manufacturer of the thermostat inside the oxygen tank. So that ultimately led to the thermostat being fried by the voltage on the launch pad during a prelaunch test. Then in flight, it didn’t protect the tank from overheating inside – actually, that had happened before flight. The wires had gotten baked because the thermostat hadn’t protected them. Then in flight, when they operated the fans inside the tank to stir the contents, the wires, which were now damaged, caused a spark with led to the explosion.

So, we have to be conscious of the playing field we’re on. Ultimately, I feel that spaceflight is a high wire act. If you think about it, a high wire is so unforgiving that you cannot lie to yourself about whether you’re on top of everything, whether you’ve done all the preparation that you need to do to be successful. You know when you’re on that high wire that even the tiniest of slips can lead to your demise.

It’s much harder to retain that awareness when you’re sitting in a conference room and having a conversation about requirements or about how many tests you can do because of budget limitations, that sort of thing. But we’ve got to keep that in the front of our minds, that we’re all walking on a high wire. Furthermore, we’re all wearing blindfolds because we all possess patterns of human behavior that are hardwired into us, that can lead us away from success. So that’s how I like to think of this.

Host: You just talked about Apollo 13. I’m just curious. Where were you and what do you remember about Apollo 13 and also the Moon landing in 1969?

Chaikin: Well, I was a died in the wool space fanatic long before Apollo started flying. When Apollo 11 happened, I had just turned 13. I had told my parents, “Don’t even think about sending me to summer camp because I will be in front of the TV for Apollo 11.” They knew to believe me when I said that.

So, when the mission happened, I was there in front of the TV every day, with my maps of the Moon and my models of the spacecraft. I even had a press kit that one of my parent’s friends had managed to get for me about the mission. So, I was doing everything I could to make myself a vicarious participant in what was going on.

Of course, I didn’t understand it nearly as well as I do now. The lunar landing itself was rather mysterious to me, and I didn’t understand what I was hearing over the radio as Neil and Buzz made that incredible descent to the Moon. But I certainly remember it vividly, and of course I remember that evening when Neil and Buzz stepped onto the Moon. I was sitting in my parents’ bedroom with them, watching it on the old black and white Zenith. It’s just indelible to me. All of the missions, really, are just an indelible part of my growing up and so precious to me.

Apollo 13, as I look back on that one, I don’t think I really appreciated the drama at the time. It just didn’t really get through to me, until I was an adult, what those astronauts had actually gone through and how close they came to not making it back. But, Apollo, to me, is an adventure that deserves telling and retelling again and again, because every time we revisit it, we appreciate it in a new way. We learn more from it. It’s just one of the great gifts to history that humanity has ever had.

Host: 50 years after the Moon landing, what’s your favorite Apollo story?

Chaikin: Right now, my favorite story is one that was told to me by Max Faget, who was the Chief Spacecraft Designer at the Space Center in Houston during the early years of the program. Max told me that one day in the 1970s, he and Bob Gilruth, who of course had been the Director of the Space Center at Houston, were walking along the beach at Galveston one evening. There was a big, bright Moon up in the sky and they were standing on the beach looking at it. Max told me that Bob Gilruth turned to him and said, “Max, some day people are going to try to go back to the Moon, and they’re going to find out how hard it really is.”

Host: Many thanks to Andrew Chaikin for joining us on the podcast today.

Andrew has conducted extensive research on the Apollo Program, including more than 150 hours of personal interviews with 23 of 24 lunar astronauts. He shared “Success Lessons from Apollo” during a recent NASA Virtual Project Management Challenge presented from the kickoff of Langley Research Center’s Safety and Health Awareness and Mission Success Week.

You’ll find a link to the VPMC and more about the Apollo 50th Anniversary Celebration at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast, along with Andrew’s bio and a show transcript.

If you have suggestions for interview topics, please let us know on Twitter at NASA APPEL, and use the hashtag SmallStepsGiantLeaps.

We invite you to subscribe to the podcast, and tell your friends and colleagues about it.

Thanks for listening.