From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

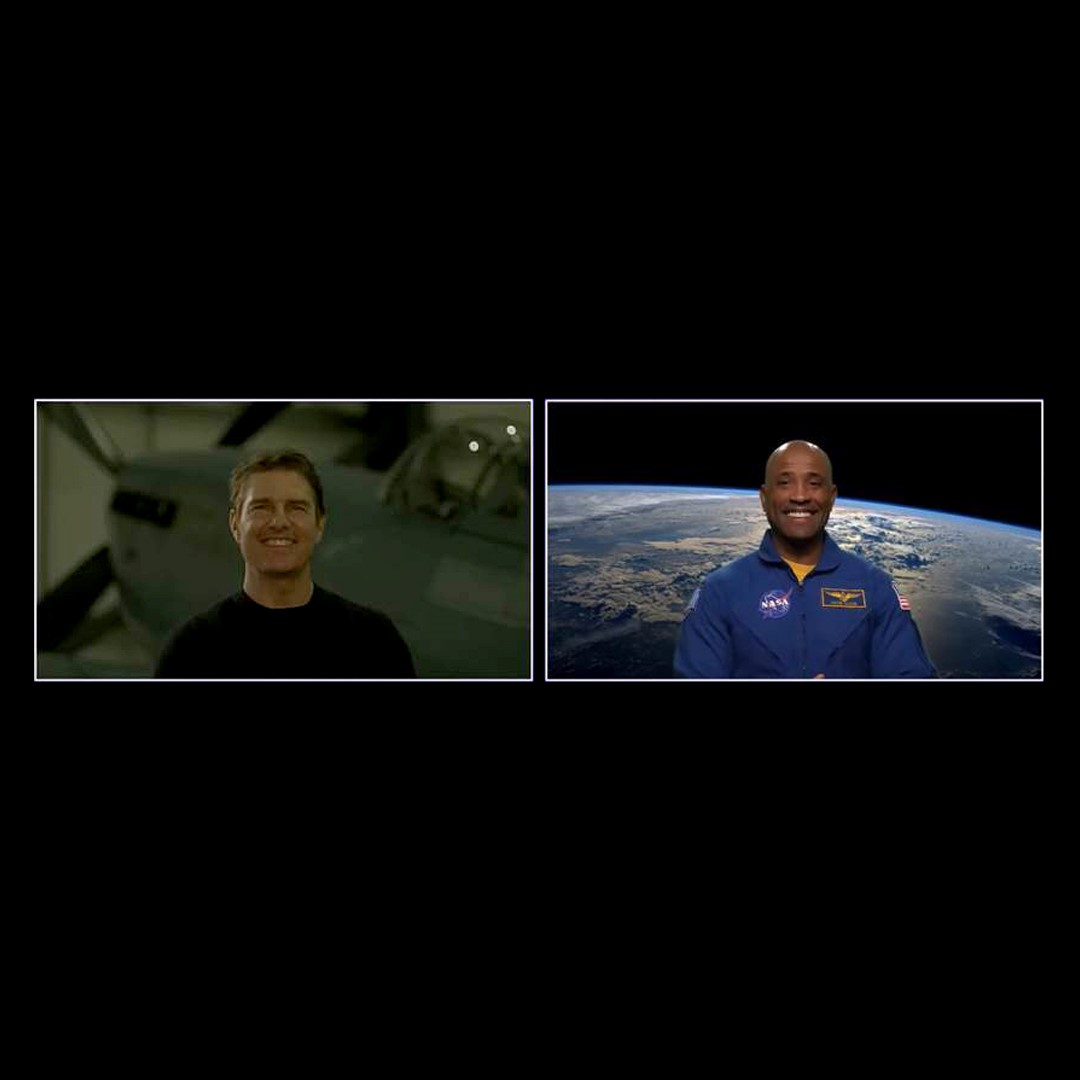

On Episode 229, Tom Cruise asks Victor Glover about what happens to the human body during a long-duration spaceflight. This discussion was recorded in November 2021.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 229, “The Body in Space.” I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be kicking off this discussion today. Listeners of this show know that the human body goes through quite a bit in space, things like bone, muscle, and vision, just to name a few, all change while a person is living and working in space. One of NASA’s goals of sending humans into space in the first place is to figure out what’s happening. From there, we can implement countermeasures to counteract some of these effects, like working out a lot to counteract bone and muscle loss, and we can conduct experiments to learn about the human body in an incredibly unique environment. What we can learn there in space can be applied on Earth and for exploring even deeper into space. Now, towards the end of last year, 2021, well-known American actor and producer Tom Cruise had an in-depth conversation with veteran NASA astronaut Victor Glover about these effects on the human body during the World Extreme Medicine conference. For about an hour, Cruise asked Glover about his experience in space, and they, together, explored some of these physiological changes. Glover discussed launching, spacewalking, the view from Earth, adapting to gravity after returning to Earth, and a whole lot more. It was a thoughtful and informative discussion, so we thought it would be great to bring it into this show for our listeners. So, on today’s episode, here’s Tom Cruise and Victor Glover. Enjoy.

[ Music]

Tom Cruise: Oh, it’s a privilege. Please call me Tom.

Victor Glover: Tom.

Tom Cruise: Victor, should I call you Victor?

Victor Glover: And the privilege is mine. It’s so amazing to meet you, even virtually.

Tom Cruise: It’s great to meet you. Congratulations on your extraordinary career thus far, it’s really, what you’ve accomplished, I have great admiration for.

Victor Glover: Well, thank you, and you know, the movie, “Top Gun,” obviously had a huge impact on me, and as much as I want to throw “Top Gun” quotes at you, I won’t. I’m sure you get a lot of that. So, thank you, because you had a part in that.

Tom Cruise: Boy, it’s an honor for me, and I can’t wait for you to see the next one, “Top Gun Maverick.” I can’t wait. It’s an honor.

Victor Glover: Oh, I can’t wait either, I’m ready.

Tom Cruise: Oh, man. [laughter] I’m ready to show it to you, I can’t wait, man.

Victor Glover: Awesome, I’m excited. I’m excited.

Tom Cruise: I have a few questions for you, if you don’t mind.

Victor Glover: Yes, sir. Let’s do it, Tom.

Tom Cruise: Because obviously you’ve flown, I guess, 40 aircraft over, as a test pilot, many different aircrafts, the F-18 as a naval aviator test pilot. Now, flying the Dragon, SpaceX Dragon, how does that compare to that, and what do you think, for yourself, what was the most exhilarating aspect?

Victor Glover: Awesome. You know, the, the Dragon is a touch screen, the displays are also where the controls are. And so that’s quite different than flying an aircraft with a stick and a throttle. And so, when I first saw it, I will be honest with you, I was like, I don’t know, guys. I need my inceptors. I need something to move around.

Tom Cruise: Yeah.

Victor Glover: But as I learned more about what the vehicle does and what its purpose was, the touch screen actually was wonderful. It worked great. And the most exhilarating part of it all was riding the Falcon 9 rocket. It is such a high-performing liquid rocket. It’s smooth, but it really leapt off the pad. And we got to the 100-kilometer point, and we were all smiles. It was just so amazing. You can really feel the accelerations and decelerations. And then once we got onto the upper stage, the second stage, and you just start building speed, it was – I’ve pulled g before in fighter aircraft, but to be able to pull g for almost ten minutes straight was just power like I’ve never experienced. Not even launching or landing on a carrier.

Tom Cruise: Really. I’ve been fortunate, I’ve got some launches, and I landed on carriers, on the Roosevelt, and that kind of g, that kind of force coming off there is pretty incredible. What was it like in the, with the Dragon? What did it feel like, the Falcon 9? I mean, how many g were you pulling, and I know you’re laying down; what was that like?

Victor Glover: Yes, and so it is different. In the fighter, the g go from your head to your toe, and that’s why we practiced these specific maneuvers, to, to keep blood flow to your brain so you stay conscious, and you don’t gray out or black out. The g in, on a rocket launch goes into your chest, and so, you naturally can, can sustain more g in that direction, and the g is actually lower. So, the maximum gwe saw was about four and a half, but what’s different in a fighter, you’ll experience, I’ve pulled 9 g in a fighter aircraft, but that was only for seconds. And, you know, I’ve sustained, so, 3 to 4 gfor maybe a minute or a minute and a half in a dog fight, in a turning fight. But, you know, on the Falcon, except for staging and throttle down, you are accelerating the entire way, for about nine minutes. It was about eight minutes and 50 or so seconds. I mean, and you’re accelerating the entire way because you wind up 200 kilometers above the Earth going 17,000 miles per hour. It’s an amazing amount of power. And so, we actually were above 3 and a half gfor about three minutes, which is amazing.

Tom Cruise: That’s incredible. That is absolutely incredible. I know I’ve had, I’ve been fortunate, you know, different aircraft that I’ve flown is, those gand feeling them momentarily, nine and a half is what I pulled, actually in the F-14, the first “Top Gun,” you know, we got nine and a half. And we, you know, in the new one we were pulling a lot of different g, but to sustain that, I was wondering, because I always wanted to know what that rocket, and feeling that acceleration, where you could actually feel that acceleration the whole time; you felt that the whole time, acceleration on the body? You could perceive it?

Victor Glover: The whole time, the whole time. Yes, you know, coming off the pad initially, it feels like a very high-speed elevator. You know, the first, the first move off the pad you’re not going very fast, and you’re actually not accelerating very fast, but it just continues to pick up. I mean the entire time, you’re moving, and at about one minute into the flight you get to, you’re in the region of maximum dynamic pressure, which you hear people say Max Q, and that’s where you’re in the thickest part of the air down low, but you’re also going really fast, and that could actually crumple the rocket and the spacecraft. So, they actually slow down, they throttle the rocket down, and you feel that. You feel yourself, it’s like tapping the brakes. And then, really, what stands out is the throttle up. Then they go back to full power, and when they do that it felt like lighting the afterburner in an F-18. I wish I would have been able to feel like it was like in an F-14, because I hear it is quite impressive, but I never got to fly that aircraft. But you definitely feel it the entire way up. And then, the first stage shuts down after about two and a half minutes, and then we ride the second stage all the way into orbit, and that one starts just at about 1 g. And so, again, it’s a very light push, but then you push for another six minutes, and about half of that time you’re above 3 g, and so, your chest is very heavy. And you have to focus on breathing, inhale, and then the exhale kind of works itself out, you know, because of the pressure. It is quite amazing. It was a truly incredible experience.

Tom Cruise: I did not know you had to work on that, that inhale. That’s incredible. That is extraordinary.

Victor Glover: Yeah.

Tom Cruise: Now, being a NASA astronaut, I mean, you require, you know, constantly pushing the boundaries, and what do you, you know, what is the most physically demanding task, both kind of before and, and after, like during, you know, during the spaceflight?

Victor Glover: Yeah, great question. You know, and I think it’s interesting to think about this. It depends on the time horizon you’re looking at. So, in the moment, the short-term, short-duration, most challenging part of what we do, I think, is training for and executing spacewalks. It’s six to seven hours of, of working and doing these very important things on the outside of the space station in the extreme environment of, of, you know, the vacuum of space, high temperatures, low temperatures, no air, and so that life support is critical. But it’s also very physically demanding. You’re moving around a suit that can weigh, with your body, as much as a thousand pounds, and you very rarely use your legs. It’s like running two marathons but on your hands the whole time. Your hands and fingers are very sore when you’re done with this. And so, that’s the most physically challenging thing. And training for it on the ground, you’re still in an extreme environment, in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab, our 40-foot-deep pool where we train for spacewalks. And so, it’s still, it’s still also physically demanding even under water. But when I think about the duration of a career and maybe something that has a huge impact on your lifespan, I think all the traveling and training and the stresses of this job, if you don’t have healthy ways to manage that stress it can actually affect your sleep. And then we also have to become comfortable sleeping in space, which is an extreme environment. We do lots of outdoor training, and you have to be able to sleep outdoors as well, so I think just looking at the way that these things, all of these stresses manifest in your life, you also have to have healthy coping strategies for the travel, all the different time zones we go in, and all the different stressors that come with the work. And then obviously then getting to space and being able to fall asleep and get the important rest that you need to accomplish your workday. That’s one, I think, is a very physically demanding aspect of training and living in space.

Tom Cruise: OK, Victor, there’s two things. One, from what I understand, and I’ve been fortunate enough to actually be fitted for a suit years ago, and just feeling the weight on Earth versus, I guess, in 0 g. But what people I don’t think understand also is what I understand, and you know this, is how hard it is opening and closing your hand, let alone – like, talk about moving the arms and moving the hands, the stiffness of the suit, because of the pressure differential, just moving your hands, the dexterity of that. Could you, could you, and then the next thing I want to ask you about is sleep, but could you tell us a little bit about that please?

Victor Glover: OK. So, yes. In that spacesuit, right, you’re in the vacuum of space. The pressure there is zero, absolute zero, so you need something to keep your fluids and your blood and to help you stay conscious and comfortable, it keeps your temperature in a comfortable range as well. And so, the suit is pressurized to 4, 4.2 pressure, pounds per square inch. 4.2 psi, and so, the entire suit is at 4.2 psi. And it wants to sit about like this. And so any time you move you’re moving against 4 pounds per square inch. And so, we have certain bearings. If you rotate your arm like this, you’re rotating a bearing. So that’s roughly, you have to overcome a little friction. But if you move like this, you’re pushing against the suit, the stiff fabric, the many layers that can maintain that pressure in the vacuum of space. And so when you close your hand, a great example, sometimes you’ll hear people say it’s like squeezing a tennis ball, but squeezing a tennis ball, if you squeeze it, it’s work to squeeze it, but then to let it go, you know, opening it, it pushes against you and helps you out. What I like to say is moving around in the suit is like putting your hand in rice: if you open your hand very wide, you’re pushing against that rice; if you close your hand, you’re closing it against that rice. And there are some athletes that use buckets of rice to train their grip strength. And I think that’s a little bit more of an accurate comparison.

Tom Cruise: Did you do things like that to increase your grip strength? Because even dropping your arm, you talk about pushing it up, but dropping your arms and moving in that way. I mean what, did you do anything physically to increase your strength with that?

Victor Glover: Absolutely. We have a great team of, we call them Astronaut Strength Conditioning and Rehabilitation Specialists, ASCRS for short. And our ASCRS craft very specific workouts to help us, like I said, training for spacewalks is also physically rigorous. And so they actually develop those workouts to help us be safe in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab where we train, and obviously to also help benefit while we’re in space. And we do very specific exercises for our grip as well as for our shoulders. Those are two of the areas that you really tax when you’re doing spacewalk training or an actual walk in space. And so, and the other thing is they give us suggestions on how to work out. For example, when I do my shoulder exercises, I originally started using dumbbells, and I would hold the handle and do my shoulder exercising, rotating and, you know, doing things to exercise my rotator cuff and all those small muscles around your shoulders. What I started doing, because of the suggestion of my strength trainer specialist, was to use plates, the same weight but in a plate, and I would pinch them so that during my exercise I was also increasing the challenge on my grip and therefore getting a better grip workout while I was exercising my shoulders. Things like that are the kinds of things that our astronaut strength, conditioning, and rehabilitation specialists help us with.

Tom Cruise: Did you feel…that’s incredible…did you feel the longer you were up there, because I want to just, just a little question on this also is, that you were there for so long, and the time when you got there and when you did the spacewalk, was there, is there, what level of depreciation of bone and muscle density is there, and did you feel a difference? Like is there, what happens to your metabolism with the Krebs cycle, with the mitochondria, did that effect the spacewalk? Could you tell the difference in terms of your strength on the ground that you built up? Is there a diminishing, is there a diminishing effect the longer that you’re in space is my question, ultimately? And how’d that affect your metabolism, your BMR (basal metabolic rate), you know, with calories and nutrition? Did you have to think about that?

Victor Glover: Yeah, great question. Oh wow, there’s a, yeah, there’s a lot packed in there. And so, I’ll, you know, that is definitely something we work hard to mitigate. You’re going to lose bone and muscle, you know, muscle due to potential atrophy from just, you don’t, I weigh 200 pounds, and I’m not carrying that 200 pounds. It’s like taking off a 200-pound backpack when I get to weightlessness. And so, I’m losing that, that effort every day, and so I have to make it up in my workout. And also, your bone density, we have this condition called osteopenia. It’s like space-induced osteoporosis. The enzymes that encourage bone growth, you know, our bones are constantly being reclaimed or eaten and then reconstituted. And in space, for some reason, the process that eats the bone or takes away bone, continues, but the part that reforms new bone slows down. And so we try to mitigate that with our strength training and also with medication. And so, the effects there can be, it can have a huge effect on you. But the workouts that we do are one of the biggest mitigators. And so, I actually started working out before the mission, and then when I got into space I continued to work out. We get two and a half hours every day to do exercise. Strength training, cardiovascular training, and then also time to clean up and get ready for the workday, and that was extremely valuable. Now, when I first got to space, my body is going through so many changes, I lost about two kilograms, and I was only eating about 2200 calories. It took me about 45 days to get used to the environment, to come up with some, you know, strategies for me to eat like I did on the ground, like keeping snacks in my pocket at all time. And when I started snacking and eating in space more like I did on the ground, I got up to 3300 or so calories, 3200 calories a day, and I was also working out very hard. So, overall, in space, I actually felt stronger than I did on the ground. I was able to work out really hard. In fact, I told myself before flight I wanted to make sure I didn’t get hurt. I didn’t want to hurt my back or my shoulders because I wanted to always be ready for the spacewalks and all of the other work on the space station. And so I felt like I could have lifted even heavier and ran harder on the treadmill, but I just didn’t want to hurt myself. But the strength training and cardio training are excellent in space.

Tom Cruise: Incredible. So, that when you were doing your spacewalks, you didn’t feel like you had lost strength.

Victor Glover: Not at all. By the time we went out the door, I felt stronger, actually. And over my mission, I did lose a little bit of bone mass. I lost about 2% of my bone mass, and they say I’ll have that recovered in about a year. Muscle mass, I actually gained. So, I told you, I lost two kilograms in the first two months. At the end of the mission though, after the complete six months, I was four kilograms heavier. So, I gained back that two and then put four more on. So, I came back with more muscle mass than I launched with.

Tom Cruise: That’s incredible. And so, you feel like that had a reflection on your metabolism overall, increased your metabolism as a result?

Victor Glover: If, I think it may have been an increase. I took a test when I got back to check our VO2 max, and so, what the VO2 max is, is a great example of how we’re doing metabolically. And so, I was in family, I was close to when I launched, and that’s what our ASCRS also are focused on helping us reacclimate to Earth and getting us back to what we were like pre-flight. And so, my strength numbers, my bench press squat, my VO2 max, we do that by getting on a cycle and going until we fail, pretty much, and they measure our gases that were inspiring and expiring, and that tells them our VO2 max. And my number was a point or two different than what it was pre-flight. And so I would say overall I was able to maintain my metabolism, and that’s pretty impressive considering all of the things that your body is experiencing.

Tom Cruise: That is impressive. Did they test your BMR after the flight to understand what that was? Did that change at all, that number?

Victor Glover: We don’t normally do that for, for crew members. I think that’s something you can get if you want to, but I was involved in an experiment called Myotones, which is studying not just muscle mass but the quality of your muscle, and it’s really looking at this device to see if we can use a very simple external device without having to do like biopsies to determine muscle tissue quality. And so, that experiment actually takes ten measurements all around your body over the course of the mission, and you also have pre-flight and post-flight numbers to compare it to. And so, I actually was able to get those kinds of measurements. But like I said, before flight, in-flight, and after.

Tom Cruise: Yeah, because you were there for six months. What was the difference? Because when we talk about going to the Moon, we talk about going to Mars; was there, was there a large difference as time went on with those numbers?

Victor Glover: Actually, I lost a little bit in the beginning and gained muscle over time, and so, I think my overall proportions stayed the same. And being able to maintain what you start with on Earth is great, that’s a great standard, but that’s very much because of the amazing exercise equipment. And if you’ve never seen it, the ARED, the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device, one of the most important technologies on the space station in my opinion. It allows us to do all kinds of exercises: bench press, squats, curls. And that machine, though, takes up almost half a module, the space for the machine plus the range of motion for the body that you put on it. And so, when we go to the Moon, we won’t be able to do that kind of workout in transit. And that’s very important to understand. We’re going to have something smaller like a rower, like an erg[ometer] that you would see on Earth. But when we get to the Moon or to lunar orbit, we’re going to need some type of a habitation module where we can get exercise, because that bone and muscle health. And also, it was a part of what I enjoyed most during the day. So, it’s also a part of mental well-being, but it’s very important to our physical well-being.

Tom Cruise: Boy. So, you feel like when we go to Mars, obviously on the planet there will be a whole module for it, but on the way to Mars, you’ll feel like we’ll need a separate thing. I mean because there was, you know, when you see “2001” we’re talking about do we put a, you know, a force of gravity, we talk about what the difference of gravity on Mars versus the Moon and on the way there. I know there’s been a lot of talk and evaluation as to what is, you know, .6 gravity on the human body, you know? We’re all, we don’t really know until we get there, and it’s done for an extended period of time. So, you feel like will we have a separate module just on the way to Mars, that’s what they’ll have.

Victor Glover: I think so because with current propulsion technology, right, we need to get better propulsion technology, because if we can shorten the duration of the trip — right now it’s going to be six to nine months — if we can shorten that trip, that means less radiation exposure and less time for your body to degrade in weightlessness. But, you know, trying to create artificial gravity by spinning one module, that creates guidance and navigation and control challenges due to gyroscopic effects, so it would actually be a little, it would be really complicated to do that, so you’re going to need to exercise. You’re going to need basic exercise. And something I try to encourage our scientists and our exercise specialists to think about is, you know, ARED is a fantastic machine, a wonderful contraption, but we also need to remember basic things. I wrestled in college and in high school, and so, I think the most amazing exercise device there is in history is another human body. That’s my opinion. But, you know, also doing calisthenics or just basic isometrics where you push on a structure. And so, maybe just getting in the corner of a module and putting your hands and feet against different sides and pushing statically against something, or using another crewmate and you both kind of do squat presses where you’re pushing against each other: those are the kinds of things we need to think about and find ways to incorporate so that we not only have the ability to do strength training, but we also have a backup in case a machine breaks. Because again, on the way to Mars, you’re not going to be able to stop off at the hardware store and get parts to fix it. And so, we need to have a way to back up those exercise devices, because it’s such a vital, a part of physical and mental well-being.

Tom Cruise: That’s a very good point. That is a very good point. You know, it’s interesting because we know what 0 g is, you know, have a great idea, I think, of what, how the body behaves under 0 g over extended period of time and, of course, on Earth, but all those experiments in terms of the Moon and on our way and when we get to Mars, how is the body at .6, you know, those different forces of gravity, how will the body develop? Are these things that you guys spoke of, and as you were preparing for this flight, did you evaluate any of that?

Victor Glover: No, we didn’t, but I do know that people are thinking about that, the scientific and the medical communities. I know that the crew that just returned, so we just launched a crew to space, you were there for that launch.

Tom Cruise: I was there. It was amazing.

Victor Glover: Well, just prior to that, we returned Crew-2 —

Tom Cruise: Yes.

Victor Glover: The crew that flew to space station after us in a Dragon, and when they got back, they actually had an activity just after launch — I’m sorry, just after landing, just within hours after they landed, we had activities where they had to climb up a contraption and move some, some large masses. That simulates being able to throw out the emergency equipment into the water, if you landed in the water in your capsule, after being deconditioned from being in space for an extended period. The Moon missions, our Apollo astronauts, they say that the worst period of deconditioning was after a 14-to 21-day mission in space, somewhere in that third week of being in space, and that’s what our Moon missions will be like. And so, coming back deconditioned, landing in the water, and maybe landing off target, we need to know that folks can operate and function in that environment. And so, we think about it, but for missions to the station we’re going to be in weightlessness for an extended period and then have to recondition to 1 g. And so, our focus is on 1 g, but I do think we need to find ways in that construct to, to evaluate things like this, you know, coming back from the Moon or being on Mars, because it’s amazing — I was just writing an email to the folks that just went up there to Crew-3, and one of the things I encouraged them to do was to learn the lessons that space is going to teach you. I used the example of the Apollo astronauts, the hop they would do on the surface of the Moon: they weren’t taught that, they innovated. They figured it out because the environment, it made sense. In that, you know, one-sixth of Earth’s gravity, they realized it was easier to hop than to try to ambulate, to try to walk like you do on Earth. And so, sometimes you just need to be in that environment. Like you said, you need to experience .6 g to understand how your body wants to operate. And, you know, the physical sense, there’s a little genius to the body, and we need to be good at listening to what our bodies tell us.

Tom Cruise: Boy, that’s incredible. I know that hop, I was always thinking, you know, you don’t want to fall, do you know what I mean?

Victor Glover: Right.

Tom Cruise: Because you can’t damage that suit at all. One thing I just want to ask, like when you did your spacewalk, what happens if you have an itch on your nose? What do you do? You’re thinking, like you start sweating, you’re going oh, my gosh, are you, one of these? I mean what’s, you can’t get your arm out to just scratch that. Did you ever have, you know —

Victor Glover: Right.

Tom Cruise: — have an itch somewhere where you’re like, man, I can’t wait until this is over, I’m going to have a good scratch here.

Victor Glover: Well, yes. I think as soon as you put the suit on and you know you’re going to pressurize it, that’s when everything does start to feel, you start, oh, is that an itch coming? But so, we actually have a device inside the suit that is for Valsalva: just like in airplanes as you start to descend and you feel the pressure build up in your ears, we have a small foam block that we can push our nostrils against so that we can force air and then expand air into our eardrums, to Valsalva. But that device is used mostly — I think I can speak for the entire astronaut corps to say — its number one use is to rest your chin on, so that you can rest, and then number two is to scratch your face. [laughter] And so, there is a way to scratch certain itches depending on, if it’s in this area, you can scratch it. But when you take the suit off —

Tom Cruise: Yeah, and the only, the only reality I —

Victor Glover: You’re — yeah.

Tom Cruise: When you take the suit off, oh, I didn’t mean to cut you off, I beg your pardon.

Victor Glover: Yeah, you’re definitely looking for some relief when you take it off. There’s all kind of little itches or aches and pains. And so, you know, interestingly, I also had, I had a situation that I almost couldn’t do anything about. So, we have this anti-fog on the inside. We dab just a few drops, wipe it on the entire visor, and try to get rid of it. And there have been other instances of astronauts experiencing that anti-fog getting in their eyes. And I don’t believe it was the anti-fog I applied to the suit. There is actually an investigation going on to find out where it may have come from. Maybe it was sucked up into the life support system and then pushed back out later, but I had three spacewalks where I felt — I did four total – -and on three of those spacewalks I had something in my eye that caused a burning sensation. And one of those happened while I was working on a pretty important piece of hardware. And so I actually had to just stop and hold still, and I just kept blinking, waiting for my eye to water, and it did, and again, my body took care of itself. And so I just kept blinking, and my eye watering, over time, it dissolved whatever that was. But it took time. It wasn’t just a small thing that the liquid pushed out. It had to dissolve something, and I could feel the burning sensation slowly decrease, and then I was able to see and finish my activity. But it felt like I was standing there out on the mast, on the very end of the space station — I was on the solar array on the space station, and I was way out there waiting for this burning sensation to go away. A pretty interesting experience.

Tom Cruise: I think that’s an understatement, isn’t it? [laughter] Pretty interesting, it was like, OK, wow. That’s intense. That is, congratulations to you. I’m glad you made it through.

Victor Glover: It was, it —

Tom Cruise: Did they figure out what that vapor was?

Victor Glover: They think it is the anti-fog solution, but there’s other things in the suit. You know, we wear a harness that can take biometric measurements. It sees our heart rate, and they can figure out respiration and understand how quickly we’re going through our oxygen and CO2 scrubbing systems. And so, we have those leads stuck to our body with an adhesive, but underneath that there is a, they call it the — electro gel, and it’s this gel that we put on before we stick them to our chest and cover them with tape. Well, that gel could have potentially leaked out as well, and I’ve never put it in my eye to see what it feels like but I imagine it wouldn’t feel very good. So, there are a few things within that sealed volume of the spacesuit that are culprits, and I’m actually waiting to get the results of the investigation, because I’d love to understand that more. At this time, I’m not sure what it was. It definitely wasn’t water, and it wasn’t my own sweat: I’ve had my own sweat in my eyes plenty of times at the gym, and it didn’t feel like that.

Tom Cruise: Incredible.

Victor Glover: Yeah.

Tom Cruise: Well, congratulations with that. Let me ask you something. You also, you had, you gave advice to, you know, to the ISS and the group that just took off; did you get any good advice as you were a trainee that you applied that you, when you were up there, you thought, you know what, I’m glad they told me this?

Victor Glover: Oh, so, so often. Before flight and even in-flight and even now after flight, you know, some of the things that really resonated. Before flight, so in training, someone said to me, actually several people said it…one of the primary things that we have to do as astronauts is to understand how the training isn’t the same as the reality. It’s our job to integrate all the training and to know how it’s different than doing it in weightlessness. And that is just so true. You get there, and everything has this one theme, weightlessness. And being in orbit can change everything. The way you brush your teeth, go to the bathroom, eat, drink, and then, of course, maintenance, science, and spacewalks. Waking up and going to sleep and waking up again in weightlessness, it’s just something that you can’t train for on Earth. And so you have to learn how to live like that and work like that once you get there. It’s on-the-job training. Another piece of advice, before my first spacewalk, was to keep your world small. That was such a great thing to think about on your first spacewalk, just going out there and focusing on one thing at a time, because it’s really easy to just want to look at the Earth, but that could be overwhelming, and since I had never done it, I didn’t want to take a chance at, you know, putting myself in a situation where, you know, the anxiety or the nerves took over. You know, I think of myself as a steely-eyed fighter pilot, but I’ve never been 260 miles above the surface of the Earth and been able to look down and see nothing under my feet. So, I didn’t want to take any chances, and I slowly opened up that view and then was able to take in the Earth in all its glory. And it was amazing, but I took my time getting there by starting small. And then, I would say my favorite piece of advice was something someone wrote on the space station. We have a sheet of paper taped to our exercise device, that ARED I was telling you about, and it actually has an acronym, PLEASE, written down the side, which tells you what to do to turn off the machine when you’re done exercising. But someone wrote a small message at the very bottom of it. It says, “nothing is more important than what you’re doing right now.” I took a picture of that and I sent it to my family, and I sent it to my friends, and I also suggested the crew that just got up there, I didn’t tell them what it was, I just told them go look at the machine and the piece of paper. I meditated on that daily. Every time I passed by it, I read it, and even sometimes hourly I would tell myself that, because it’s really easy to focus on a spacewalk, but you know what? When I was repairing the toilet, I thought, it was just as important as going out into the vacuum of space. Nothing is more important than what you’re doing right now, because everything that we did in space was so vital.

Tom Cruise: That’s, that’s words of wisdom for life down here on Earth, too. It’s an incredible thing. You know, when you talk about space, when you were talking about your purview or your view expanding, my question is, have you skydived before? Have you gone through skydiving and scuba diving? Did you do a lot of that prior to this?

Victor Glover: You know, I’ve never been skydiving, and I would love to. I would love to do that, and I hope NASA can integrate that into our training. Our cosmonaut colleagues do that as a part of their training, and so, maybe I need to go evaluate the cosmonaut training program so that I can do some skydiving. But I did learn to scuba dive. I actually learned to do it in Guam while I was on a Navy deployment there and before I became an astronaut. And then as a part of this job, when we train in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab with the full pressure suit on, that’s considered full pressure suit diving. But sometimes we’ll do a practice run without all the other divers and the cameras, by ourselves just with our buddy, and we’ll go down in scuba the run before so we can see where things are, how we’re going to attack the problem with the tools, and how we’ll get out and back from the worksite as a team. And so, we do lots of scuba diving in this job. And that is, flying and diving are two of the parts of this job that I love the most.

Tom Cruise: That’s a great job. I’ve got to take you skydiving. I’ll take you skydiving. I’ll teach you.

Victor Glover: Yes, yes, please.

Tom Cruise: I’ll take you. We’ll do that.

Victor Glover: OK.

Tom Cruise: We’ll do that, OK. I’ll call you after, and I’ll figure it out. That would be fun. That would be really fun.

Victor Glover: Awesome. [laughter]

Tom Cruise: So, when you’re up there on the spacewalk, was that the most astonishing view that you had? Was that the moment for you? You know, everyone talks about inside, obviously the Cupola, we’ve seen those shots and film of that, but outside and looking back at Earth or, you know, what other things, what was, did you see anything else? Or just share a little bit of that with us, if you don’t mind, please.

Victor Glover: Wow, absolutely. You know, because you’re inside the space station, the windows there, you know, it is a great view out of the Cupola, and we have other windows, but when you’re outside on a spacewalk, that visor wraps around you so that you can, you actually have peripheral view. And so when you can see the Earth, there’s nothing besides that visor between you and the Earth and the vacuum of space. And so, that is just the most unique way to see the Earth from orbit, and it is truly breathtaking. That’s why it’s important to keep your world small. If you walked out and the first thing you do is just stare at the Earth, I mean, you may be stuck in that for several minutes, and you’ve got work to do in those first few minutes. And it’s also important to keep your heart rate low in the first few minutes. I can tell you more about that later. But that view is very special. It is extremely special. But I think the view that impacted me the most was the first time I saw the Earth from orbit, and that was after launch. We got to orbit safely, and now, we had 27 hours before we were going to catch up to the space station and dock. And so we had time to take off our suits and eat and go to the bathroom, and I went to the window and looked out. And first of all, the orientation of the Earth, I thought, you know, that I was just used to seeing the Earth like you see it in this picture, you know, horizon there and the Earth down. And it was like sideways, and I felt like I was underneath the Earth and I’m looking out, and I was just amazed at the view, how much detail that I could see, but then how much of that detail. And so, I just grabbed my iPad, and I started recording a video. And it wasn’t that I wanted to share the imagery with people. I wanted to capture the feeling that I was just awestruck, and I wanted to share that with people, how, how it impacted me. And so, that really was a powerful moment. And you know, I think the, the Overview Effect, if you’ve heard about that, seeing the world without borders, without labels, just as it is; seeing the magnitude and the majesty but also the fragility of the planet, has an effect on most people who get the privilege of flying to space. But it also, since I’ve been back for a little over six months now, I realize that it’s important, and it is amazing, and it’s a privilege to see it, but one of the reasons that it’s so powerful and it’s so impactful is because of what you build up over your life here on Earth. Seeing an entire ocean, an entire body of water from space is amazing. I could see the entire ocean, but it makes you still want to stand on the beach and walk in the surf. And so, it’s the fact that it connects to your experience on Earth. Being in space just accelerates that and makes you appreciate the planet and appreciate the life that it supports, the fragility of the Earth, and the preciousness of human life. And so, it’s one of my missions now to try and remind people of that right here on Earth, that we already start the overview process — The Overview Effect starts right here in 1 g on the surface of the Earth with each other.

Tom Cruise: That’s spectacular. That’s really amazing. Thank you. It gave me new images of what that experience must be like. That’s amazing, absolutely amazing.

Victor Glover: Thank you. It’s powerful. The Earth is amazing, it’s amazing.

Tom Cruise: [laughter] It really is. Well, you know, when you came back, did anything, you know, in terms of, I know we talked about, physically, calories and nutrition, was the food, did you pick your food ahead of time? I mean these are like, did you, you know, physically what were you going through? What was it like eating the food there? Did it change? Was it different eating it in 0 g than it was on Earth? Did you change your calorie count? Did you change your diet specifically for it? Did you, you know, did you get advice from nutritionists saying how it changed, or was it pretty much the same on Earth as it is in the space station?

Victor Glover: Yes. A topic that I really care a lot about. I love to eat, and, you know, the food on space station is great. We have great variety, and that’s because we’ve spent years improving it, sort of going from like MREs (Meals, Ready to Eat) like we have in the military to reducing the salt, increasing variety and options. We do pick a little bit of the food. There’s a standard menu up there that we all share, and then we are able to pick about 10% to 20% of our food, and they can even go, depending on the packaging and if it will last long enough, because your food is up there for a year or years before you get there, and so, it has to have safe packaging and be shelf stable for long enough. And so, I had lots of advice. We had nutritionists in a food science lab where we can taste the foods, and the value in that is you know what the entire menu is like, but it also gives you a chance to start thinking about ways to combine and recombine the food to add even more variety to it, or using one, like I used a lot of tomato basil soup as sauce for other things, putting it on the chicken breast, for example. It just added a little bit of flavor. And so, those kinds of things are very important. I also got lots of advice from my crewmates. And in fact, I don’t think I took that advice well enough when they told me, really think about the stuff you can choose — I picked one or two things, and I was really happy that they had these dry fruit strips that I really like. And so, I was like, OK, great. And I’ve got my coffee. And I wish I would have spent more time and like gone to the store and dedicated some time to looking at different things and seeing, hey, I could get that, I could have a few of these, and adding even more variety, just maximizing variety and taste and textures. Because of six months of eating the same things, it is really easy for it to become boring and routine. And so, we constantly are finding ways to — adapt and keep it interesting. But yes, eating in space, you adapt. You know, utensils; you don’t use utensils like you do on Earth. You don’t scoop out your soup. Honestly, you cut the corner off — not all the way off, because now you’ve created a little piece of trash that’s going to float away that you have to go chase — you just cut the corner open enough so that you can get the soup out, and you just, you kind of suck it out of the bag. We do a lot of eating like kids do, like toddlers drink and they eat their food out of pouches. We do that often, and so you don’t need utensils as much as you do on Earth. Drinking water, you know, you need to be careful because the water floats, or all of your drinks float, and so, you have to really be intentional. When I first got there, I was trying to have a drink, and I was talking to one of my crewmates, and I briefly choked. And was like, whoa, OK, no more talking and drinking. I’m just going to focus on one at a time because this is a new challenge. And so it definitely changes the mode in which you do those things. And there’s just things that you have to learn in space, and you have to learn the lesson space has to teach you. Hot things. Hot things can be really interesting. You know, on Earth, when something is warm, like your coffee in a mug, the warm air is less dense, and so it wafts up, and you can smell it. And you don’t have that sense of smell in space. You have fluid shift, which makes you feel a little more congested, and you also don’t have gravity to create that differential that makes warm things rise. So, your foods don’t smell as strong, and it affects the taste. And so, we use a lot of condiments to, to make things taste better. But also, you don’t have the sensation of heat. When you pull a hot package out of the, the food warmer, if you’re not holding it, you don’t sense the heat like you do on a hot plate of foot with the warm air rising up to you. So, you really need to check the temperatures of your food. When I ate my first bag of warm tomato basil soup — my first one in space was cold — the first time I heated it up I cut the package open, I made a big cut, too big, and so soup was starting to come up out of it. And I put my face down by it, and the soup, as soon as it touches your lip, surface tension and capillary action take over, and it wants to spread over your face. And so, that’s how I found out that it was really hot. And so, I grabbed it off my face with my hand, but it was really warm, and I surprised myself. And so, that’s not something you think about on Earth, because you can sense the heat, and then you can get a spoon out and sort of slurp it and check it, and in space, you just have to really be careful about your hot foods. And that’s just true about everything. Space requires constant attention. It is mentally fatiguing because everything you do requires constant attention.

Tom Cruise: Yeah, the temperature inside the ISS, I mean obviously, it’s closely monitored. How did that feel for you? The atmosphere inside, the, the air, the smell of the air being different. Was there any other things in terms of the electronics of the ISS, and did you feel a difference being in that space? I mean just the EMFs (electric and magnetic fields), or you talk about radiation, you know, those things in terms of being surrounded by so many electrical devices and the radiation, did you, could you tell and feel a different environment with that on your body?

Victor Glover: Yes, it’s interesting. The entire space station is controlled to about 22 degrees Celsius, 72 degrees Fahrenheit, and so, it feels very much like your home except for all the air moves in space station because of a fan. You know, there’s no natural circulation, and so, because of that, if you stand in one place too long and you talk as much as I’m speaking right now, you build up a bubble of CO2, you know, and that definitely has effects, one of the most common effects of high levels of CO2 are headaches. And so, you can also experience air hunger, kind of like the sensation just before you yawn. And so, those are things that happened that are kind of compartmentalized depending on where you are and the activity that you’re doing. If you’re working in one area for a long time, you may want to have an extra fan, bring a fan with you to blow air out as you’re sitting there breathing and adding CO2. But the temperature was very comfortable, but depending on where you’re working, sometimes I would go up on the overhead, and we generally would have inlets on the deck, and the outlets for the air conditioning were overhead. So when I would be working up on the ceiling, on the overhead, I would be really close to the airflow, and you know, with this haircut, it was easy to lose a lot of heat. And so, when I was working on the overhead I would grab a hat or a knit cap, and I would wear that. And even sometimes I would put on my hoodie just because if my head was losing heat it made my entire body feel cold. And so, it really was local-specific. The entire space station was very comfortable, but depending on where you worked, you may want to be in your short sleeves or you may need a jacket to stay warm. And then the smell, it’s very interesting. When you first get to space station is when you notice the smell the strongest because you kind of get saturated and you get used to it after, but it was an interesting combination. And again, it’s also local. When you go into the module that has the lifting, the strength training equipment, that’s also where the bathroom is. So, that’s the most odoriferous module. That one smells like a locker room. And so, the overall space station, it smells very much like a factory. It has this machine, sterile, metallic quality to it. It very much smells like a workspace. You know, when you walk into a hospital, you sense that, yeah, this smells like a hospital. It’s got this antiseptic, germ-free quality, and so, we work really hard to keep it clean. And it just, you know, between all the machines and the fans on the computers and the power boxes on all the hardware, there’s this hum, and there’s a smell. There’s a visual, and there’s a sound of the space station that kind of, it’s almost like a living thing, and it’s neat because if that ever changes, you know the ground did something or something broke, and all of us would hear something shut down and go, uh-oh, something just changed, and the ground would call you. So, you get used to all of those qualities of the space station. It’s almost like another crew member up there that you get used to the personality and the characteristics of ISS.

Tom Cruise: So, it’s always that electronic sound throughout. You just —

Victor Glover: All day.

Tom Cruise: — that never stops.

Victor Glover: All the fans and electronics, there’s a whir, a hum that just is continuous, and if that ever stops and it gets quiet, quiet would actually make us all go, uh-oh, what’s wrong? Did we just lose power? What happened? Because there is always some machine running, 24 hours a day, 365, 366 in a leap year, it’s always moving.

Tom Cruise: So, you feel the vibration when you’re sleeping. Was it hard to make yourself fall asleep and stay on a schedule with that? Did you feel the vibration, you’re hearing the noise? Did you have ear plugs?

Victor Glover: We have ear plugs. We also have, you know, sleep medication if you need it. If you wake up and you have trouble going back to sleep, we have lots of options there. I think I was very fortunate. I did not use ear plugs because I wanted to be able to hear if the ground called us or if there was an alarm in the middle of the night. And we actually had several, about a half a dozen times where we were woken up in the middle of the night. Once it was three times in one night, and you don’t ever want to discount them. You want to take each one seriously. And so, I wanted to hear, but I didn’t have trouble falling asleep, and a part of that is because we sleep in crew quarters. All of us except our commander. We increased the normal size of the space station crew from six to seven, and so, we didn’t yet have an extra room. We call them crew quarters, and they’re padded on the inside. So, when you shut the door, it has its own fan, and other than that fan and your computer, or music if you have music playing, you don’t hear much when you’re in your crew quarters. And that’s great; you can hop in your sleeping bag and for me, I didn’t like to tie my sleeping bag down very tight. Some people tried to re-create the sensation of sleeping on Earth, and they would put a pillow and try to squeeze themselves up against the wall and create the sense of pressure that would mimic laying down. And I just tried to embrace the floating. And so I tied my sleeping bag at the waist in two places, and the rest of it, I let it float. And so, I just slept out in the middle of the module, and my body was in whatever its normal, relaxed position was. And I slept great. I slept great on the space station, and I actually needed less sleep. I averaged seven hours a night, and on Earth I try to get eight hours a night. But at seven hours, my eyes would fly open, and I would be rested and ready to start the day. That was very interesting.

Tom Cruise: And did you feel a difference in your sleep on Earth from, when you came back? Did it, when you, the gravity, did it change any? Did you feel any physical effects?

Victor Glover: Coming back to Earth, I had to get used to lying down again, and then especially sitting up. My midsection was so weak, so weak compared to before I flew, that when I would sit up, it was a concerted effort, you know. And then, just getting stable and then standing up, that was an interesting thing, to lie down all night and then sit up. But overall, the sleep quality, I think my sleep, once I was asleep, was very much in space like it was on Earth. And that was nice, because sleep is very important to me. Just, food, sleep, flying, those are things that I very much love. [Laughter]

Tom Cruise: I appreciate that. By the way, speaking of flying, I’m talking to you now from England at a great, you know, airfield, Duxford, at the, it’s a restoration center. This is a Spitfire behind me right here. You know, so these guys, I don’t know if you can see it on the scene.

Victor Glover: And that is, I can, and it’s beautiful. Mark told me where you are, and that is, I’m jealous. This is a cool view —

Tom Cruise: I know.

Victor Glover: — but there’s no airplane behind me. That’s awesome.

Tom Cruise: That’s a very cool view. This airplane, you know, that’s what we’re doing. We’re flying a bunch of stuff, and you know, working on, we’re releasing “Top Gun,” and we’re working on mission. So, being a fighter pilot, I know —

Victor Glover: I’m jealous. I’m jealous.

Tom Cruise: I know, man, we’re going to — I’ll be flying this thing when I get off here, we’re going to go fly some Spitfires. We got Mustang here too.

Victor Glover: Oh, very cool. Wow. Well, fly safe.

Tom Cruise: If you’re ever in, where are you now? Are you in California? Where are you?

Victor Glover: I’m in Houston.

Tom Cruise: Oh, Houston, nice.

Victor Glover: Just south of Houston.

Tom Cruise: Well, tell me if you ever get to California. I have a P-51 out there. You can go have a flight if you want it. You just tell me —

Victor Glover: OK, so –

Tom Cruise: I’ve got a P-51. So we can go skydiving and a little P-51 stuff.

Victor Glover: In test pilot school — oh, OK. You had me at hello. Yes, sign me up. [Laughter] I flew 35 airplanes in test pilot school, and two that I never got to fly, that I always wanted to fly, were the F-14 Tomcat and the P-51 Mustang. The test pilot school wasn’t able to get a P-51 that year. Sometimes they do, but we didn’t get one. So, that’s on my bucket list.

Tom Cruise: Well, good, man. I’m going to get that bucket list for you. We got some good pilots taking you through it.

Victor Glover: Oh, deal. Awesome. Thank you, thank you!

Tom Cruise: We’ll get that done.

Victor Glover: Awesome.

Tom Cruise: Now let me see, we talked through your science experiments. I’m going to kind of look at the questions that we had written down. I want to make sure; you know…we went through the sleep, OK. And you know, one of the things that I’d like to discuss also is the team dynamic, the preparation for that. I mean being in such close quarters, you know, obviously, you went through the Air Force Academy, you know, you know the preparation. You know and understand the military teamwork and the flow of communication. Was that different with the ISS? Was that different with this team? Is there, you know, did you find in terms of, everyone under stress or personal conflict and how to resolve those conflicts when you’re there so that it’s, did you guys have to have, you know, that kind of training in terms of dealing with that, those situations when they arise?

Victor Glover: Absolutely, absolutely. And I think it’s time well spent. And that’s what I would say. It takes intention, and it takes time. You have to put in work for self-care, learning how to take care of yourself and understanding what gets you going and what makes you stop, and then also team care, how you fit into the role of a high-performing, high functioning team that has to work in this isolated, confined, and extreme environment. And so, I think the, the effort that we take on the ground in training is really to give you a tool bag, a set of tools that you can use when you need them, and it’s important to understand them as a suite of tools, because just like spacewalking and science you really don’t know what it’s like until you get there. There’s a part of your mission that is going to affect you socially and emotionally, and you don’t know how that’s going to affect you until you get there. For example, on Earth, I would consider myself an extrovert’s extrovert, a type A extrovert. I love being with people and communicating and telling stories and hearing stories, and that gives me energy. On the ISS, if I had a free moment, I wanted to be by myself, because you’re constantly engaged with things and people and getting instruction and giving a report, and there’s so much extrovertism that I needed to just be by myself to recharge. And that surprised me. And so, so it’s important to have your tools so that in space, in the moment, you can actually contrive something, you can use the basic building blocks that we study on Earth to create whatever it is that you need when you’re in the environment. I like to tell this story about, you know, working together. It’s important to train with folks on the ground so that you know them. And Mike Hopkins, our Dragon commander, he and I were together for three years prior to this mission, and over time we developed a couple of things. We would say, hey, if we’re ever talking to the ground, and you hear me say something and you think I’m being too pushy, you know, we both played college football and so we came up with this saying, “take a knee,” “take a knee.” And that was if we thought we were being too pushy with the ground or with each other, “take a knee.” And we agreed, we had trust in each other that if we ever heard that, it was an automatic stop, and then we would do whatever our other crewmates suggested. And we also came up with another saying over time that was if we were doing something that, you know, maybe seemed tedious or we had just done it, and the ground said, hey we need you to do this, and we could tell that that might be a frustrating item for each other, that we would say over the, over the intercom or if we were floating by, we would just say, “this is the mission.” You know, we’re both military officers also, and sometimes you just got to follow orders and salute and carry on. And so, we would say to each other, “this is the mission.” And over time, because the TV show “The Mandalorian” was out, and in that, they say, “this is the way,” “this is the way.” And so, we adapted it, because we loved watching “The Mandalorian.” We took a baby Yoda to space as our 0 g indicator. And so, we started saying, “this is the way,” and we actually used that one all the time. And it was mostly in humor. It was mostly a joke, you know. We’d hear something come up from the ground, and we’d be in a completely different module, and one of us would yell, “this is the way!” You know, and everybody would laugh because we understood what was going on. But the other one, the “taking a knee,” we never had to use that in space, but I think it’s important that we had to come up with that, and I think because we put the time to develop a system to hold each other accountable but also to build trust, to use that system of accountability, I think that’s one of the reasons that we never actually had to use it. And that’s a good thing. I think that’s a win. And so, overall, though, it’s important to intentionally take time to do self-care and team care training and then to have the time dedicated to doing it. And sometimes we’re going to have to do it in real time. We’re getting ready to launch a private mission to the space station, and as we do that, we’re going to have less time to be together on the ground. And I think it’s important for us to consider time on the space station that we dedicate solely to building team camaraderie and morale, so that those folks can be effective, as effective as they can be in space. Because again, it required intentionality, and it requires time.

Tom Cruise: That makes total sense. That makes total sense. That’s excellent. Also, just going on the journey, six and a half hours to the space station, what was that like? That’s six and a half hours. At a certain point, you’ve had the g. You’ve had the ride into space, and now you’re just, did you feel like, OK, I’m ready to get there, let’s, you know, what was going through your mind beforehand? Were you thinking —

Victor Glover: So, you know, it can be, it can be as short as about six and a half hours, or it can be much longer. Sometimes it can take up to two days. In the Soyuz, it used to take 48 hours; they can get there as short as six hours. And so, our rendezvous actually was in between, it was 27 hours. And so, after the exhilarating ride of about nine minutes into orbit, we had over a day before we could dock with the space station, and you know, it was, that’s when I had my first view of Earth from space. I had my first meal — macadamia nuts and cold tomato soup — and the first time I got to use the bathroom in space. And so it was fun, but after trying to go to sleep, that’s when I realized, OK, I’m ready to be on the space station. Because I slept in my chair so I could see the displays: if something happened, I would be right there at my workstation ready to, you know, get back to piloting Crew Dragon Resilience. And so, you actually don’t sleep well in the spacecraft. You really nap. It’s really — snacking, instead of having a meal, and napping instead of getting a good night’s sleep. And so, after just taking naps over a day, when I got to the space station I knew that that was where I was going to get my first good sleep, so I was ready.

Tom Cruise: Very cool. That’s very cool. Now, you are, also, you’re the first crew that landed at night since 1968, since [Jim] Lovell and [Bill] Anders and [Frank] Borman, the Apollo 8 mission. Now, what was that like? I mean how aggressive was the landing? What happened immediately after splashdown? I mean what, you know, what was it like coming back six months later, hitting the water? Did you feel, was it rocking? Did you feel the impact of the water? Was it, did they have some special system that carried you a little bit, that took some of the load in the chair?

Victor Glover: So, it is actually a really neat thing to come back to Earth after six months. You know, when we first hit the atmosphere, we do a deorbit burn, which decelerates the spacecraft so it starts to descend. And then it hits the atmosphere and the drag of the air starts to slow it down. In fact, that drag, you’re going so fast that friction heats up and it ignites the air around the vehicle, creating a plasma cloud. That’s why you come back to Earth in a fireball. And so, that heatshield is doing its job. But that’s also when you start to feel your first gagain. And so, as the g on the spacecraft builds up, you start to feel your weight again, and that’s really interesting after being weightless for six months. That’s the first sensation. Then when we got to about 18,000 feet, the drogue parachutes come out and so, the g has been coming up, and so, just like on launch, the g is into your chest because now we turned the spacecraft backwards to put the heatshield into the wind, so the pressure is still going into the chest, making it hard to breathe, you feel like your face is doing this, being stretched out. And so, you get to 18,000 feet, and then the drogue parachutes come out, and that is very visceral. The vehicle moves, and you feel it swaying. We call that a Dutch roll. It’s like rolling and pitching and yawing all at the same time, and then it stabilizes, and those drogue chutes start to slow you down and get you into the envelope where the main parachutes come out. And then those big parachutes come out, and they reef. They start off very closed, and then they open slightly and then open all the way over time. And so, you can actually feel that. It’s almost like hanging onto the end of a bungee cord. When they first come out, it jerks the vehicle, and you kind of bounce. You almost feel like you’re going over a bump in a car. I felt a little bit of a light sensation after feeling the first g. Then to feel weightless again was very interesting. And then they widen out and slow you down again, and so you feel again the same jerking sensation. And then, from about 6000 feet down to the surface, you’re riding under these big four parachutes, and we were, we touched down doing about 27 feet per second. If you sky dive, you know most parachutes get you between 20 and 30 feet per second, or seven meters per second, when you touch down, and that’s about what sport parachutes bring you down to the ground at. So, that’s about the same velocity that we hit the water with, and you know, the water is a nicer place to touch down than the land. And so, the touchdown was actually quite soft, because it gives; the spacecraft settles into the water a little bit and then rebounds and then bounces. And because it was night, and the seas were nice and calm, it felt like we were just gently rocking. You couldn’t see the horizon outside, so there wasn’t a sense of, you know, disorientation, which I was very worried about. It felt nice and calm, like I was sitting in a rocking chair just going back and forth. And it actually felt very good. It felt very comforting. However, it was at that time, I’m now back in 1 g, I feel my 200 pounds, and that’s when I noticed I had to pee. I could also feel the weight of my bladder for the first time, and it was a really interesting sensation…

Tom Cruise: Wow. Wow.

Victor Glover:…after not having it for six months. [laughter]

Tom Cruise: Wow. For six months you did not have that feeling at all?

Victor Glover: Well, not the weight, you know. It’s really interesting because you have to really go regularly and encourage yourself to go, because by the time you feel that it means your bladder is really full, because you don’t have the weight. It means it, you know, volume-wise, it’s filled up. So, yeah, to feel the weight again now, it was like, whoa, I’ve got to go now.

Tom Cruise: [Laughter] And what about your strength otherwise when you got up and started walking again. What was that like?

Victor Glover: Yeah. So, you have a recovery crew that gets you out of the sea, takes you out the hatch and gets you to the edge of the vehicle, once we were up on the boat, right? And so, we’re still on the ocean, you know, on the recovery ship, and things are swaying. And now, like I said, I’ve been working out, eating well in space, and I felt strong. I felt really strong. And we get up, and I’ve got two people helping me, and I get up, and I feel strong. Standing up, I can easily lift my weight. But then that ship motion, it rocks one way, and my head almost hit the person on my left. I mean my head felt so heavy. And then it goes back the other way, and my head feels so heavy. And I was really grateful that I had people helping me because had that rocking motion happened and I was standing up by myself, I would have tumbled over to the ground. I felt really strong, but I had no sense of balance. I was a 45-year-old toddler. It was really interesting because I know how to walk; it’s in there, the memory is there, but it was really difficult to ambulate. I could stand up, but I could not resist the rocking motion of the ship.

Tom Cruise: How long did it take for you to recover that?

Victor Glover: Interesting question. So, yeah, I wrote it down in my journal because it was interesting. Every hour I got a little more capability back. It became a little more comfortable, and it was about the four-hour point, we had flown a helicopter off the ship to Pensacola, and at Pensacola we had to go through a series of tests to sit down, stand up, lie down, and stand up to check orthostatic intolerance, to make sure our heart was pumping sufficient blood to our brain to keep us conscious. And so, doing that test is when I realized, OK, this is the point where I would be comfortable, you know, building a habitat on Mars or on the Moon. And so, if you fly to Mars, it’s going to take you six to nine months. I was on the ISS for six to nine months. You’re going to get to Mars, and you’re going to be in about a third of gravity of Earth, so that’s going to be different, but you’re going to be back in some sense of weight, and it’s going to take me about four hours to get to the point where I can comfortably move around and get myself out of the vehicle. That’s a data point that I very much wanted to know and to keep. So I wrote it in my journal, and those are the kinds of things I think we need to extract from ISS missions as they relate to going on, you know, our Artemis program is going to get us to the Moon to stay, and then eventually onto Mars, and we need to start capturing all of those lessons about how our bodies are affected.

Tom Cruise: Were your fellow astronauts, was it the same time period for them, those four hours, or was it…

Victor Glover: Just observing, you know, I’d just see them doing their thing, yeah. I think it was about the same, maybe some a little sooner, maybe some a little slower, but I think about that time we were all feeling good. And then a few hours after that we flew from Pensacola back to Houston, and our families were there to meet us at the airfield. And each one of us was able to walk down the stairs of the plane and walk to our vans to then go back to the crew quarters, the quarantine facility. And so, I think all of us were about on that same recovery pace.

Tom Cruise: So, how long before you felt, you feel you could fly an airplane or, you know, drive a car, ride a motorcycle on a racetrack. How long for that?

Victor Glover: So, the doctors evaluate us for about two weeks, and they generally won’t let you — even if you tell them, doc, I feel great, they make you wait two weeks. And so at about two weeks I felt like I could have driven a car. I probably would have waited a little bit, I did, I waited a little longer before flying. Actually, I waited even before driving. They let me have a driver for three weeks, and so, I took advantage and just kept the driver for three weeks. And I started driving at three weeks. I felt great. And so, it was about a month after that I started flying again, and I’m glad I got back into flying early, but I didn’t go too early. I didn’t want to have to worry. Flying is already hard enough and takes enough focus and attention that I didn’t want to add onto that now worrying if my ability, just because I had returned to Earth, was going to be there. So, I wanted to wait until I knew that I was ready.

Tom Cruise: That’s also another interesting thing to keep in mind in terms of when you land on Mars or the Moon, if you’re operating machinery, how long that period from, will it take to get there, that 0 g, to then before you’re able to start handling different kinds of machinery or, you know, how ambulatory can you be. What kind of stress can the body, and not just physically but mentally, can you handle once you get there.

Victor Glover: Right. And I had a special team. Those ASCRS that I keep bringing up, such an amazing group of folks, that I had dedicated two hours every day working on strength, balance. We were doing toe touches and bending down to the ground, standing on one leg, you know, standing on the BOSU balls to work balance. I had a professional working with me every day for two hours, seven days a week, to help get me back, and we did that for 45 days. So, again, you’re right, that is absolutely the kinds of things that we need to know so that crew members can do those things for themselves, because you’re not going to have, you know, this amazing training team with you there on Mars. You’re going to have to know what works and what doesn’t work, and you’re also going to have to know, I’m not going to drive a forklift right now because I would be a danger to myself and my crewmates and that forklift. So, it’s going to take me probably 45 days before I’m going to do the really high value, high risk operations.

Tom Cruise: Well, that’s really interesting. Now, Victor, I could talk to you, I could stay here all day, and we have a worldwide audience of Extreme Medicine…

Victor Glover: Me too. Me too.

Tom Cruise:…listening, listening to you, you know, and they want to use the medical training as a powerful force for good, pushing the boundaries of extreme medicine. Now, is there anything that you would like to say to them now, give them a message before we close?

Victor Glover: Absolutely. Yes, thank you. And thank you for this opportunity. That’s what I want to say is thank you, thank you, thank you. You know, as our planet is still, you know, experiencing this pandemic, I think all of us have healthcare workers and professionals and janitorial workers and professionals on our minds all the time, and then you add something to that, you know, in church, it really impacted me when I was young, and I heard someone say to me, you have to meet people where they are. You have to take your gifts to people. You have to meet people where they are. And I think of the extreme medical community as not only this great group of folks that provide healthcare, but you do it in isolated, confined, extreme, and hostile sometimes environments. You take this life-saving care and meet people where they are, and so, I just want to express my gratitude and my awe that you are able to do things that most people can’t even do so that you can provide healthcare to people in these extreme circumstances. Thank you. I think what you do is commendable, and I look up to you. And I really want to be like you. I hope to engage in more training for extreme environments and, you know, they say imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and I desire to be very much like you all. Thank you for your service.

Tom Cruise: That was excellent. I agree with you, Victor. You are impressive, and what you’ve accomplished thus far is absolutely impressive. Absolutely engaging, incredibly informative, and I’m grateful to be here, and I’m grateful also to all these people out there that are helping people and just want to thank you. You’re going to get your P-51…

Victor Glover: And Tom — yes, sir. Yes, please.

Tom Cruise: It’s ready to go, man.

Victor Glover: And it’s so amazing to talk to you. Oh, I’m ready to go.

Tom Cruise: I’m ready to go too, man.

Victor Glover: And thank you for this. It has been a treat. I showed up, I showed up here today, and you know, I saw this on the calendar, and I read the papers and stuff, but I still asked my public affairs team, this awesome group of pros, and I said, hey, guys, I just want to get this straight: so, Tom Cruise is going to ask me questions today? [Laughter] I just figured there was a typo somewhere. So, this has truly been a treat. Tom, thank you so much for the time, and I hope you enjoy flying that Spitfire. That is, that’s going to be amazing.

Tom Cruise: Thank you, man. We’ll get you the P-51.

Victor Glover: Awesome.

Tom Cruise: I enjoyed this immensely. Incredibly informative. I’m just very grateful to have this opportunity and thank you.

Victor Glover: Same. Me too, thank you.

[ Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. I hope you enjoyed such a great conversation today. We really enjoyed it, hearing Tom Cruise and Victor Glover chat with one another. They were both very excited. So, I hope you learned something today about the human body in space. We actually have a website if you want to check out more, if this has really sparked your interest. It’s the Human Research Program. They’ve collected a lot of different research that they’re working on now and some of the things we know about the human body in space. Just go to NASA.gov/hrp if you want to dive deep. We also have a number of episodes on this topic and others, just what’s happening to the human body. So, you can check out our full collection at NASA.gov/podcasts. You can find us there, Houston We Have a Podcast, our full collection, listen to any episode in any particular order, anything that really sparks your interest. There’s also a number of other shows all across NASA, the agency, that you can find there at that link. If you want to talk to us at Houston We Have a Podcast, we’re on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram under the NASA Johnson Space Center pages. You can use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea or ask a question. Just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This discussion was recorded in November 2021. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Heidi Lavelle, Belinda Pulido on the podcast team, as always; thanks to Megan Dean and Katie Spear at NASA, to Jack Wood and Professor Mark Hannaford and others from the World Extreme Medicine Conference, and to the folks at 42 West for helping us to share this conversation on Houston We Have a Podcast. And of course, thanks again to Tom Cruise and Victor Glover for taking the time to have such a wonderful conversation. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.