If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

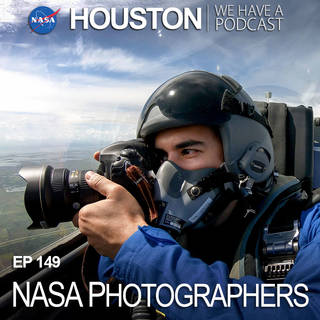

On Episode 149, James Blair, Robert Markowitz, and Josh Valcarcel are among the NASA photographers who find themselves in the second seat of a T-38 jet, or taking studio portraits, and everywhere in between, documenting history and the many facets of human spaceflight. This episode was recorded on February 4, 2020.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host):Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 149, “NASA Photographers.” I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight. You know you’re into spaceflight, if you have a rocket launch, an astronaut or a photo of Earth from space as the background of your smartphone. Imagery is just one of those things that’s hard to beat when it comes to how people engage in human spaceflight. Those famous shots of astronauts walking out in their spacesuits, those shots of celebration at Mission Control, astronauts training, flying jets, they’re iconic photos. But as you can imagine, these photos are among the few of the millions of images collected here at the Johnson Space Center. Helping to capture history, share technical data and more is a small team of photographers here at NASA. We’re bringing on a few today James Blair, Robert Markowitz and Josh Valcarcel. Each of these fine gentlemen are out and about almost every day capturing history. And to do so, they sometimes find themselves in some of the coolest places at NASA. So here we go, what it’s like to be a photographer at NASA with James Blair, Robert Markowitz and Josh Valcarcel. Enjoy.

[ Music]

Host: Robert, James and Josh, thank you so much for coming on Houston, We Have a Podcast today.

Josh Valcarcel: Thanks for having us.

James Blair: Good to be here.

Robert Markowitz: Oh, yeah.

Host: Alright. So, this is the first time we’ve done it with this many people. I’m excited to talk to you guys because I see you all the time [laughter]. Everything we’re doing, you know, we do events, we do mission commentary, and you’re always there. You’re always there documenting. And you have different roles and different ways that you approach these tasks. So, I’m excited to hear how that’s all done from your perspective. I want to get a little bit of backstory because I — the reason why we have you all here is because you come from different backgrounds, different levels of expertise in different ways on how to approach this. Robert, we’ll start with you. What’s your background? How did you end up at NASA?

Robert Markowitz: So, I grew up actually in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. And then after my first year of college at University of Oklahoma, decided to go to photo school and went to Rochester Institute of Technology up in Rochester, New York. And had a little job right after graduating from there in a little town outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and wasn’t really overly happy with that job. So, started looking. So, a lot of times it’s background, knowledge, expertise, as well as timing. The photo department here used to have — all the photographers used to be civil servants. In 1987 they decided to split them and make half contractors, half civil servants. And so, my supervisor right now, Mark Sowa joined in 1987, as well as several other photographers. And one of those decided after a few years to leave the group and go get a civil servant job over in the astronaut office. And so, it opened up a slot about the same time I was looking for a position. So, I joined the group in 1990. And have been here — this August will actually be 30 years as a photographer. So, kind of neat. You talk to a lot of people. You meet a lot of people out here. There’s tons of people that have worked here, you know, 20, 30, 40 years, but most of those have worked in various areas, various disciplines around JSC. So, it’s pretty unique to actually be one that’s worked here now for 30 years and being in the same job, same discipline, doing the same, same work. So, it kind of is a testament to how much I think we enjoy our work out here.

Host: Same discipline, but really, I mean, I’m sure things are changing all the time and of all the people you must know everyone [laughter]. Honestly, because you have so many different areas that you’re hitting right?

Robert Markowitz: Yeah.

Host: And you see some of the same people in different roles.

Robert Markowitz: Exactly. And you see them grow. Sometimes you see them come and go. Sometimes people will be out here for five, 10 years, leave do some different roles and realize how good it is here at NASA and then they’ll return. And so, it’s definitely interesting seeing the evolvement over time.

Host: Oh, look at that. Congratulations on 30 years. Quite an achievement. James let’s go on to you. What’s your background?

James Blair: I have a slightly different background from Robert. I started out — I graduated from [Southern Methodist University] SMU with a degree in anthropology of all things. But I worked at the school newspaper and was the photo editor there, had a fortunate enough to have a mentor from the Associated Press by the name of Eric Gay who, who was a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer. And he mentored me while I was in college. And he kind of showed me the ropes and led me to photo journalism. And after I graduated, I went to work at various newspapers around the country kind of hopped around at medium small newspapers as a photo journalist. Enjoyed it a lot. Enjoyed shooting people in sports. There’s a lot of adrenaline involved, and it was fun. Then I happened to be freelancing for the Associated Press in Austin and just heard about the job through a job at NASA opening through a friend of a friend. And I think I may have been the first photographer to submit a portfolio on CD-ROM [laughter]. That kind of dates me. So, and I was lucky enough to get picked and since then, it’s been great. There’s definitely a learning curve of going from a true photo journalist to working at NASA, doing a lot of studio portraits and production, photography. So, it’s been great.

Host: Yeah. So, what are those key differences if you had to sum it up into a paragraph of what it takes to go from the photojournalism from Associated Press to being a NASA photographer?

James Blair: As a photojournalist, you’re almost kind of a fly on the wall, you’re telling a story and you’re trying not to get yourself involved with the story itself. You’re just documenting it. And with NASA quite often, you are setting up imagery, setting up scenes, trying to show the public the capabilities of NASA and the hardware and the engineers. So, I had to kind of learn about positioning people and lighting people and where in photojournalism, there’s minimal lighting and you know, just trying to let that story happen in front of you. So —

Host: Yeah, you’re worried more about the moment when it comes to photojournalism because you want to capture that versus the artistic maybe —

James Blair: But I mean, that still happens here. Working for NASA you’re capturing just incredible moments of the crew returns and mission control and EFT-1 where you’re trying to capture emotion and the incredible, you know, experiences people are having here at Johnson Space Center.

Host: Yeah. Now Josh, are you in the CD-ROM era or are you a little bit afterwards?

Josh Valcarcel: No, I have a website [laughter].

James Blair: He has Instagram [laugher].

Josh Valcarcel: Instagram, yeah.

Host: Alright, so what’s your background?

Josh Valcarcel: Alright, I got started in the Navy. I had no idea what I wanted to do after high school. And I joined the Navy, like a lot of people do. And I saw that photography was an option. And I said that I wanted to do that. And there’s a whole story that goes along with this. They said that that was a, you know, a field that was filled up, hard to get into. A lot of people want to do it. And I chose two others as backups. I lied. I really only wanted that one job. I never intended to join the Navy if I didn’t get it. But there’s a long-delayed entry program. You know, they’re working with me for months, they take me down two hours, you know, to process. And at the last minute, they say, you know, that job photographer isn’t available. And I just looked at him, I was like, it’s going to be real long ride home [laughter]. So, he looks at me and then he goes back into the room. He comes back out. He’s like, it’s just, you know, it popped up. You know, you’re so lucky. So that’s how I got started. I called this recruiter on his bluff. It was the best decision I ever made [laughter]. I never had any experience with photography prior to joining the Navy. Went to boot camp after boot camp. They put you through a four-month crash course. At the time it was basic still photography. And I was one of the last classes to learn on film in the beginning, for about a month. And yeah, it was amazing. It was a joint service school. The Defense Information School is in Fort Meade, Maryland. And they just run you through the gamut, awards, ceremonies, grip and grins, documentation, combat photography, studio portraiture, everything you can imagine they just — that’s your life. And then they just spit you out into the fleet. And I was lucky enough to go to San Diego, at the Public Affairs Center Pacific there. And so, I basically worked a day job. But every year I would deploy on a different ship and augment their media department. So, I deployed on three different boats. I went to over 20 different countries in the time I was in the Navy, which is about five years. Yeah. And got a lot of experience. Unless you do something really stupid, they’re not going to fire you. So, I had lots of opportunities to fail confidently, which I still like to think that I do. And after the Navy, I went to college. I went to the Brooks Institute, which at the time was this legendary — I hope still now a legendary photo college. That is now extinct. It went away. It was unfortunately mismanaged. And, you know, it went under, but the time I had there and what I learned was just immense. I like to think that the Navy taught me how to take pictures, but Brooks taught me how to tell stories. And so that’s why I took leaving college. Timing worked out in such a way where in my last year of school, I really gravitated towards science. I felt that that was a subject that was — they just didn’t seem like a lot of photographers were gunning for shooting scientific subjects and I had this natural kind of inclination to it. And so, I decided to go that route. I really fell in love with Wired Magazine. I found a ton of Wired magazines in the school library, and I just kind of like, start checking a bunch of these out, love the style. And I decided I want to work for Wired Magazine in my last year. And there’s a whole chain of events that happened but as soon as I graduated, two weeks later, I was working there as an online photo editor and staff photographer. So, did that for three years. It was amazing. I got to help make a magazine every month. See how that process worked. It was super creative. It was super open. If you had an idea, you can take it across to another desk. And if they liked it, you can collaborate and synergize. I did stand ups for video. I wrote a few stories. I went to Comic-Con. I went to the Consumer Electronics Show. It was just a whole different world. And that’s where I really got into product photography. That was pretty much my world, was shooting products for reviews. And, you know, so I did well there. I was brought on as a contractor initially at Wired, then I got hired on as staff. And then in my third year I was laid off because, you know, publications are kind, like tumultuous industry. It happens. It was a really dark time. It was a really, you know, insecure moment. But I like bringing that up because the you know, the time of greatest doubt came right before, you know, the best time of my career which is getting my job here at NASA. It was just amazing. Again, fortunate turn of events. I looked and there it was. And I think it’s important to note that Robert mentioned earlier we’re all contractors. So, the job title didn’t say NASA photographer. It said, scientific photographer for my contractor, Analytical Mechanics Associates, which on the surface, what is that? You click on it, and it’s the job description. It’s just being a NASA photographer. And it sounded amazing. So, it was kind of hidden. I applied to that, you know, I had no idea how the system worked. Applied. didn’t hear anything back. Two weeks later, you know, my girlfriend and I looked on LinkedIn, we found out who worked here. We found, you know, Robert’s LinkedIn. We found our supervisor Mark’s. And I emailed Mark and I said, “Hey, I just want to reiterate my interest in this job.” It was a Sunday night. Following morning, he emails back saying, “We didn’t get your application.” I guess the company had stopped sending them to him. It didn’t open for like two weeks already or more. And so that’s how I got an interview that week and ultimately got hired. So, now I’ve been here for about two years and eight months now.

Host: A little bit of luck, a little bit of persistence. What a story.

Josh Valcarcel: For sure. Yeah.

Host: That’s awesome. I love your phrase “fail confidently,” that was —

Josh Valcarcel: Right on.

Host: Yeah, I like that a lot. That’s really good. That’s a great way to learn is to do and have that kind of freedom to express different ideas and themes. And if it works great, if it doesn’t —

Josh Valcarcel: You learn something.

Host: Yeah, you learn something. I wanted to go back, one thing that I kind of locked on was right in the beginning, you said you were going to the Navy and you wanted photography. And then the two others were lies, but you really want photography but had no prior experience with photography. What was it that drove you to that?

Josh Valcarcel: They had a magazine and it was a silly photo of just, you know, there’s something to do in the Navy where you man the rails — coming back into port after deployment. All the sailors put on their dress whites, and they line along the edges of the boat. And they had a picture. It was a panoramic and above each sailor they all look the same. That was the point. But they had jobs written above them and pointing down to each sailor so you can see what they all did. And one of them said photographer. I never thought that you can do that in the military. So, I was like — that’s what I want to do. That’s how it jumped out at me. That was the first step. I don’t know why I felt so — it just seemed like the fun thing to do. I like to draw. My brother is a cartoonist. So, I just like artistic stuff, anything I could do creatively. So, it just seemed if I was going to get through the military, I had to do something creative, to give myself the best shot at being successful, and just kind of getting through it. And so, I just kind of went on good faith. But I will say that the only epiphany I’ve ever had in my life was when I was — my first day of photo school, which was August 9th in 2005. I remember it, because it’s like a birthday for me. And it was the day we clashed up at DINFOS, the Defense Information School. And they show you your [single-lens reflex] SLR and lenses is the first time I’ve ever held one. And they take you on a tour of all the different rooms and aspects of the course that you’ll be introduced to. And they had print rooms, you know, you saw photos that students had taken up on the walls. And I just had this feeling, you know, I just had this feeling that very, you know, potent sense. This is what I wanted to do the rest of my life. Like I’d found something that I had somehow managed to go this long without getting exposed to this way directly. And I just felt like, “Oh, this is my thing. This is what I’m going to pour my heart and soul into.” And I’m 15 years in now. And I feel like it’s proof that that was real. That that sense, that feeling I had was absolutely authentic.

Host: Wow, that’s significant. It starts with just looking at a magazine saying, “Hmm, I want to explore that more.” And then next thing you know, you’re set. You’re rock solid. This is your life.

Josh Valcarcel:Yeah. It sounded fun.

Host: Yeah, for sure. Alright, so let’s kind of explore what being a NASA photographer is all about. Robert, we’ll go back to you. Thinking about what you’re doing. I don’t want to say on a day to day basis, because that’s probably not accurate, but a snapshot of all the different things you’re covering.

Robert Markowitz: Well, what’s funny is, Josh mentioned first picking up a camera in 2005. Was that correct?

Josh Valcarcel: Right. Yeah.

Robert Markowitz: So, I’d already been here for 15 years [laughter]. But I think you kind of, you know, hit the nail on the head with the key thing about being a NASA photographer is we wear multiple hats. And we basically do something different every single day. So, a lot of people, you know, you have food photographers, you have people that photograph furniture, you have people that photograph models, whatever it is, but they’re doing the same thing every day. And I knew in college, I was very interested in the corporate, annual report style of photography. So, I knew that early on that that’s the kind of photography I wanted to do. So, you know, after college, I went and applied for — I probably sent out 200 or more resumes across the country, just because I knew I wanted to do it. So, I send it to the Boeing’s and all those kinds of companies. And so, when I, you know, found this job, I knew it was the perfect fit. And so, the coolest thing is, is that, you know, one day you could be photographing the center director, you can be photographing his official portrait in our studio or in his office. You could be doing an award ceremony. But we also get into severe or high-end technical photography, where we do high speed photography, time lapse photography. Like James said, production shoots, we find ourselves in different environments. All three of us have actually flown and qualified on the T-38 aircraft. James and I have photographed in NASA’s Zero-gaircraft over multiple of years. Back in the day, we actually — my supervisor and I were actually trained and performed underwater photography. Back in the early days when we had the WETF here or the Weightless Environment Training Facility, both he and I actually got trained out here and then when our bigger pool got built to handle the space station assembly, Mark and I actually dove for a number of years, four or five years out in that facility. And, you know, we would document activities like the Hubble Space Telescope repair missions, the initial assembly of International Space Station. So it was that variety that has kept it unique and interesting over the years and it continues to do so this day.

Host: Yeah, yeah. One of the things that jumps in my mind is, what is, what is it about being a NASA photographer for 30 years that makes you want to continue to do that? It sounds like it’s just — it’s never boring. You have a different day, you have a different mindset, you get to learn new things. You get to be certified in all of these different things in aircraft, underwater, not in the same day, obviously. But [laughter] I mean, it’s just — it’s new. It’s a unique experience. Just said Zero gravity. This is incredible. James, tell me about some of those moments, like, you know, being certified for flying in the T-38 or what’s that like to go through that process and then start taking aerial photography.

James Blair: That was probably the pinnacle of my career here was putting on that flight vest and getting into a T-38. So yeah, that was a dream come true. As a kid always wanted to fly in a jet. I didn’t quite have the right stuff to make it through the Navy or Air Force. So, I just feel incredibly fortunate to be able to do it for NASA. And even better, I get to take photos while flying in the backseat of a T-38. It’s amazing. It’s probably also one of the most exhausting assignments [laughter] you’ll have. it’s exhilarating. So, you’re working with adrenaline plus you’re fighting with your harness that you’re in. And you’re trying to twist around and dealing with g-forces and it’s amazing. It’s a dream come true.

Host: So, Josh, what are you doing on those flights? Are you just taking, you know, nice cool photos of planes? Is there a technical aspect to it that helps pilots to learn or to understand how things working?

Josh Valcarcel: So, I’ve only flown twice. My first was a checkout flight, which was just, you know, getting adapted to the, you know, the craft. This is what it feels like. And the second flight was a video shoot to actually shoot T-38’s information. And it was a video shoot. And I can attest everything James just said, it’s exhausting. I had to take Dramamine so that you know, I wouldn’t get sick. And it was the first shoot I had that was, I had an assignment where I actually had to hold the camera up. And when the aircraft starts to move, you start taking g‘s and the camera weighs 60 pounds all of a sudden. And you’re trying to hold it steady out the window or you know, you know, pointing outside and it starts to just come towards your chest. And you’re pushing as hard as you can against it and it’s still coming towards your chest. Your body is shaking and you’re wondering, “How am I going to get a clean shot out of this?” Not to mention the canopy is wide open to the sunlight. It’s pouring in. There is reflections everywhere. You’re trying to look through your mask at the LCD screen. You have a limited range of motion. You can barely turn your shoulders. So, it’s just a really fun challenge to try and solve [laughter]. That’s my explanation of that.

Host: Fun. I don’t know why you pick that word fun. That sounds — yeah. I’m exhausted just listening to it.

Robert Markowitz: An important note to make is, especially in the T-38 environment, but whether it be in that environment, or almost any shoot that we go on, we’re in situations where you have one chance to get the shot. And so, it costs a lot of money to get those aircraft up in the air. It costs a lot of money to put us in the backseat. So, when we’re tasked to do a job, we need to make sure that we come out there with the best imagery that’s possible. So, you know, some of the environments that I was in, and some of my flying — so I mentioned earlier about the Zero-g plane. Well, it’s always nice to have photos and videos of the outside of the Zero-g plane performing its maneuvers. So, the public can see it, they can use it in videos and posters and things like that. So, we actually — one of the flights went into a T-38 and had to mimic the exact flight pattern of the Zero-g plane. And because T-38s really aren’t made to be in that type of environment. Yes, they can go you know, Zero-g, negative g’s, plus g’s, but it’s really not meant to be in a Zero-g for any sustained length of time. So, the Zero-g plane is usually about a 30 second period of weightlessness, where it’s going from 36,000 feet to about 26,000 feet for that Zero-g time. The T-38s aren’t really meant to be in that configuration for that amount of length of time. But usually what we did was do about four parabolas. We do two parabolas and do still pictures and then we do two parabolas and capture video. After that you’re done. So, you better make sure that you got those images during that time.

Host: That’s it, you have two chances for stills, two chances.

Robert Markowitz: Right.

Host: And that’s it. [multiple speakers].

James Blair: A lot of preparation involved for each flight.

Host: What kinds of preparation? What do you —

James Blair: You want to make sure you’re very familiar with your camera equipment you’re going to use. You want to make sure it’s the appropriate camera equipment for the job. Know your settings, know your lighting and you want to take as little equipment up in the T-38 as possible. You can’t bring two cameras. You can’t bring backups. Just because of the size constraint, there’s no stowage anywhere. So, it’s key to know your stuff when you go up.

Host: So, when you’re putting on — you talked about different hats that you have to put on. You have to put on your technical hat. You have to put on your artistic hat. Let’s put on the technical hat for just a second, Josh. When you’re putting on the technical hat, what is it that you are focusing on? What is it that you have to get out of this technical photography and deliver to who?

Josh Valcarcel: So, these guys taught me how to think this way. One of the things I had to adjust to was shooting something for engineering purposes, or for analytical purposes versus for outreach, or basic documentation. And sometimes they’re totally separate shoots and other times they’re happening kind of at the same time and you’ve got to switch hats on the fly. And one of the things that I learned and James, you helped me a lot with this early on was, sometimes you’ll just have an object. And you’ll go from shooting the event, you know, the training that’s unfolding, till they pull you aside, and they say, “Hey, take a picture of this thing.” And I’ve learned now that what they mean was, they’re not looking for a pretty picture, although I’m going to make sure it’s well exposed and visible, you know. But the primary purpose of that is to show information that then they can analyze and do science with or you make assessments from. And so, you know, I don’t need to make it perfect. I just need to make sure that it’s legible. And from certain angles, you know, probably get everything they need. I have developed a sense for, you know, trying to cover all the bases. That’s pretty counterintuitive to a photographer who’s thinking about composition most of the time, and aesthetics. All that goes out the window. And now I’m thinking about content and readability.

Host: So how do you know what to capture, James? What are some of the lessons you’ve taught Josh? How do you know what to capture? And then how do you know when it’s your time to go in during a test or during this moment and then take these photographs and what angles to take? And what would be most beneficial from the eye of an engineer?

James Blair: Sure. I mean, first is talking to the engineer and asking them what’s the key moment? What’s the key item? What should I be looking for? What gizmo, what action? You know, they, you know, are there scratches on the surface of the item, you know, you want to light it a certain way to highlight those scratches? Or bringing the proper lens, the macro lens and lighting it properly, getting close. And quite often they want you to get inside an item and piece of hardware and light up the inside and just knowing how to do that. Yeah, just communication is key when it comes to engineering. And yeah, it’s definitely different from public affair imagery.

Host: Yeah, and they’re not photographers, either. So, when they say, “I want that, and I want it well lit.” You’re like, “OK, I’m the expert here. And I have to figure out how to do that to get the results that this person is looking for.”

James Blair: Exactly.

Host: Robert, you mentioned some other stuff, too. You mentioned like time lapses and images over time, you know, stills, videos, everything. They want good data to make assessments.

Robert Markowitz: Right. So, the other side of the coin of that technical capability of knowing how to expose things well, know what the engineers are looking for, is to keep up with the technology. So of course, when I started, we basically only did still acquisition. So, we were still photography department. Video was actually accomplished from a different department. So, we didn’t have to worry — we only had to know, and of course, we didn’t have digital cameras then, and it was all film cameras. So, we just, you know, had to know our, you know, normal 35-millimeter still cameras, medium format still cameras. We also did four by five. So, you had to know that older technology. That’s all you need to know plus the flash equipment, everything like that. Of course, then when we transition to digital, you know, that technology became a little bit more difficult interfacing with the computers, the computer software. So, the learning curve, you know, became a little higher. And then a number of years ago, we actually acquired the video acquisition portion. So now we do both still and video. So now in addition to all of the, you know, standard, still photography equipment, we also have to keep up with all the video technology, the cameras, the audio, everything of that end. Plus, the technical — the other types of — all phenomenal types of acquisition, right? So, the time lapse, the high speed. So high speed photography, you know, 30 years ago, we also captured on traditional film. So, we used Millican cameras. They held 400-foot rolls and we shot mostly at 400 frames per second speed cameras. And now it’s all transitioned to digital. And so now you have to learn the new technologies of the new cameras. And of course, the frame rates now of these cameras go up to 10,000 20,000 50,000 frames per second. And that’s even still on the slow end of things that we’re capturing. So, you’re constantly keeping up with, you know, the changes, the technologies, how to utilize them, how to, you know, choose the best equipment to give the engineers exactly what they need.

Host: How do you keep up with that then? Are you getting a — signing up for a bunch of different magazines and reading them as you get the time? Do you set aside time in your job?

James Blair: It used to be magazines now find anything on the internet. And YouTube is a great source of information about new technology. So yeah, it’s transitioned. But yet we have to stay on top of the new trends. Absolutely.

Host: Yeah, that’s got to be big for it. Alright. Now, let’s put on a different hat. I know Josh, you talked about composition when you’re thinking — you have to switch away from your composition style of thinking to the technical. Now going back to that composition, what’s a moment as a NASA photographer where you have to think about that and use all those skills?

Josh Valcarcel: I would say most of the time from virtually everything you’re shooting. If it’s an award ceremony, you’re still thinking about aesthetics and composition, lighting. You’re trying to make everything look as good as it can, regardless of what you’re doing. If it’s an educational event, you know, children are engaged in learning. You’re trying to get them the best photo as possible for them. Or it’s an astronaut getting ready to suit up to go into the NBL. You know, you’re doing the best you can with the lighting available with the lighting you can bring in. And even if you’ve shot it tons of times, you’re still trying to give it the attention it deserves in the moment. Because this is pretty unique, you know?

Host: Yeah.

Josh Valcarcel: And yeah, we do, do things on a day to day basis, but history is still being made every single day. And I remember the first time I went to the NBL, James took me there. And it was an astronaut getting suited up. And I remember just getting so excited. I still get excited when I go over there. But I was just taking a ton of pictures and you know, James, I can’t even imagine how many times you’ve shot this. But I come out of there, I, you know, we leave, we go back to the office, I’m still there, but it’s like, they’re making history over there. You know, it’s just like I was so jazzed by it. And it’s just really important to, like, not lose sight of that. Because, you know, after 20 times of doing it, it’s still the same, that same feeling I had from that first moment. It’s the same truth, you know. So just I got to make sure that I hang on to it and apply everything that I know, everything that I’ve gleaned from my career so far, to making it as powerful and as impactful as possible as it is.

Host: Yeah. I know one of the key moments I’m thinking about some of those NBL photos. I like — there’s always one where they have to put the astronauts on this rig. They’re fully suited up. They got all their umbilical’s and they move this giant rig and they start dipping them in the pool. And there’s this moment where they just they’re just submersing. They’re going underwater and a lot of them do something. They throw up like they wave, or they throw out like horns or you know, thumbs up, whatever. They do something like that. That’s like a moment that you know is coming and you’re like, “I have to be ready to capture that.” Maybe one of the few that are a little bit predictable other than that you’re just looking for your moments.

James Blair: True.

Host: Yeah. So, let’s talk about going under the water. You talked about both of you went under the water and did some photography there. Now what’s it like to, you know, Josh described having to hold this camera against g’s and film in a plane. Now what are some of the techniques you need to film underwater?

Robert Markowitz: I think it actually when you ask the question, I think about it, it all has to do with trying to predict where you need to be to get the best shot. And I think no matter the environment you’re in, whether it’s, you know, voting on the Zero-g plane or capturing imagery in mission control or at the NBL or underwater, you always want to try to be in the best position to capture the most interesting, the picture that will tell the story the best. Give the engineers the information they need, but also be cognizant of your location to make sure that you’re also not getting in the way. You don’t want to be blocking flight director’s view of the front screen. You don’t want to be, you know, getting in the way of suit technicians slowing their process down of suiting up the astronauts. You always need to be cognizant of where you’re at, what you’re doing, get your job done, but make sure you’re not inhibiting other people getting their job done.

Host: Yeah, fly on the wall, just like you were saying. Yeah, you have to be there, be present and capture the moment but not be in anyone’s way. People are trying to do jobs.

Robert Markowitz: One of the things that you also kind of brought up with doing part of the creativity was, you know, being a NASA photographer, you have to kind of do things a certain way. There’s a certain, you know, method and a certain, you know, look that NASA imagery, you know, expects and the program expects, and the center director expects. So, we’re always cognizant to get those pictures kind of in the back. And so that’s, you know, if we’re doing an astronaut portrait in a, you know, spacesuit or something like that, there’s always the shots that we need to get or a crew portrait. But the nice thing is, is that with they always leave us room for creativity. So, there’s been many times where, you know, we could spend, you know, an hour with a crew member on a portrait and make sure we get all of our, you know, shots that we need to get that NASA needs. But then it gives us some time to do some creative shots of the crew member or crew portraits. And oftentimes, unexpectedly, when the crew member is deciding what pictures they want to best represent them or best represent their crew, they’ll sometimes go with those creative shots that were kind of off the cuff that we just come up with, you know, during a session. So, it’s always you know, neat when those kinds of situations arise.

Host: Josh what’s it like working with astronauts? And how it differs from astronaut to astronaut and what they’re willing to do to be creative?

Josh Valcarcel: Well, I think it’s really important to follow up with what Robert just said to make sure that everyone knows that Robert is the photographer that shot Leland Melvin with the two dogs [laughter]. Which is my favorite shot.

Host: That is a famous one.

Robert Markowitz: It has become quite recognizable.

Host: Yeah, wow.

Josh Valcarcel: So that’s huge [laughter]. So, my favorite part of working here is having the astronauts in the studio. It’s a controlled scenario. There’s an opportunity there that I never want to not take advantage of. And they’re all just so nice. They really are like, that’s one of the most beautiful things about interacting with them is this not only are these just incredibly capable individuals, but they’re just, they’ll listen to you, you know. They’re present. They’re just good people. And I feel like they’re just great subjects to shoot. And I want to show that, and I want to convey how that feels. And so yeah, we go through the — we do the official shots, there’s the list of things that we need to knock out. But I always try at the end of every studio session to carve out whatever time I can have left to do something creative, to do something different. To apply some kind of vision behind it. I’ll have a different backdrop set up. I’ll have different lights set up. And I’ll Have the radio transceivers ready to just switch to a different channel. So, at the very end, I just switched to hit the switch, drop the new backdrop down and take advantage of whatever time is available, whatever time they want to give me and do some creative portraits. I’ve done some stuff in black and white that I’m really proud of that’s been really fun. I kind of worked out a series that I’ve been chipping away at. It’s just you know that these people are going into outer space and coming back, and it’s just kind of amazing. Like I’m at a loss for words to really describe it, but I’ll say that there was some that I had in the studio. You know, let’s take Luke and Drew that are up there right now. They just finished the AMS Spacewalk. Not only did I get the opportunity to shoot them both in the studio in their [Extravehicular Mobility Unit] EMU suits, I got to photograph them training on the — the basically training for the [Extravehicular Activity] EVA that they just accomplished. I got to document that a lot. And then I’m in mission control, taking pictures of the flight controllers with them on screen in space, doing the spacewalk, and I’m familiar with the activities that they’re going through. I can see what they’re doing. And I know, oh, this part is really complicated, because I’ve seen them work through this, work this out in real time on the ground. And that’s huge. Putting people in outer space and then bringing them back home. And they’re effectively your coworkers.

Host: Yeah, yeah, you’re going on the journey with them.

Josh Valcarcel: Pretty much.

Host: They’re training, and you can see them preparing for what they’re about to do in space, then you’re there. So, I mean, I’m sure you just want to turn the camera around and take a picture like, “Look, I’m here, I took the journey with you.”

Josh Valcarcel: Right.

Host: But you know, everyone else did too. Everyone else took the you’re trying to capture the flight controllers, because they put a ton of work into it. The engineers because you know that they’re putting — they’re giving everything they have to train these crew members to do this task. So, you are right there with the same emotions that a lot of these trainers are feeling and trying to capture that and document that.

Josh Valcarcel: 100 percent.

Host: And not just the technical aspects, but yeah.

Josh Valcarcel: Yeah, it’s monumental. I don’t know how many societies are capable of putting human beings in outer space. You know, throughout history, this is relatively new. It’s not something to take for granted.

Host: Yeah. Now there’s a lot of historical elements to this. And we’ve talked about all these different moments, all these different techniques, all these images that you’re capturing. We talked about the movement to digital. With digital comes a new way of taking photos, and that’s snap, snap, snap, snap, snap, snap, snap, right? You’re taking a lot. I’m sure it could be on the order of thousands a day. So how do you shift through that? How do you shuffle through and pick? These are the ones we’re going to send to people? These are the ones we’re going to post publicly? These are the we are going to archive?

James Blair: Sure. I mean, yeah, I started out shooting film and going to an event shooting, you know, three or four rolls of 35-millimeter. I thought that was a lot. But with digital, you can — digital doesn’t cost anything. You just shoot and shoot. And you have to kind of hold back sometimes and remember, slow down and think more about the shots you’re going to get. But when you get back to the office and you start screening your imagery, I think unlike your traditional photographer, we have like, we’ve been saying you have to put on different hats and you have to select imagery for different customers. It may be one assignment, but there are different people who are going to use your imagery from that one assignment, whether it be public release, or engineering. And so, we generally pick a larger group of images for all customers. The public release imagery, you’re looking for that right moment with a nice smile on the face, and the right good lighting. But the engineering documentation is a little more subtle. You generally shoot a larger volume of imagery because you never know quite what the engineer — what detail that engineer is looking for. So —

Host: That’s a different way of thinking about it. Because in one way, if you’re trying to document, you want the best documentation. And from your mind as a photographer, you kind of have a better idea of what is the best moment and what’s the best style, what’s the best angle to document. Now, with the engineering aspect of things, you’re not in that mindset, because you don’t know what is the best. So, you have to almost do everything.

James Blair: Yeah, with engineering documentation quite often you’re documenting every step of the process. So, you’ll end up with sometimes hundreds of images. And mixed in with those hundreds of images is a select few public release images you would consider.

Host: Wow, Robert, I can’t even imagine what this was like before digital because you’re talking about going through hundreds of images and saying, “Here you go engineers, like this is this is what you requested.” Was it the same with film or did they just not get the right data? How did that work?

Robert Markowitz: I think we definitely shot less. I’m thinking of some, you know, back in the shuttle days when they used to do the emergency egress activities, either in Building 9, [Space Vehicle Mockup Facility], practicing there or egress activities out at the NBL that we used to. So it was, you know, full suited events. And those were, you know, multi-hours, usually three or four hour, you know, suited events for, you know, a crew of seven. And we’d be out there the entire time. And most of that we used — in the early days, we used to shoot on medium format film or Hasselblads. And, you know, I usually shoot probably what’s called a brick. So, like five rolls of 24 exposure, and, you know, if it was, you know, a busy shoot, you may shoot two of those. So, in the realm of it, it’s still not very many today, on an event like that, you probably easily shoot 500 to 1,000 exposures. You know, I just photographed a retirement ceremony last night for a director that’s been here for you know, over about 46 years that just retired. And you know, it was a well-received event and she had tons of people there celebrating her work out here. And you know, I, just my raw images, I shot nearly 700 pictures. So, you know, you’ll get back to the office because you want to make sure that you captured it correctly and captured all the people that were important in her life. But you know, you’ll come back, and you know, maybe submit a couple of hundred from that. So, you know, you’re always shooting a lot more, but it enables you to get really the best shot possible. So, it’s really been — digital has definitely been a great thing for photography. It’s definitely added more work on the back end than the than the front end. People sometimes don’t realize the amount of time it takes to screen through all of those hundreds and thousands of images sometimes. But it does allow us to capture, I think better imagery in the end.

Host: Yeah. So, what do you think is more intensive, processing thousands of digital images or converting film into something usable? I don’t even know how that worked.

Robert Markowitz: It’s definitely intensive screening through. And it depends on the event. Sometimes, some things are easier to screen than others, depending on what you’re looking at [laughter].

Host: Yeah, yeah, that can be absolutely true. It sounds like Josh that there’s these barriers when it comes to being a NASA photographer as to what you guys are responsible for. It seems like you get a request to, to photograph something. And then there’s a period of time where you have to look through the best of that imagery and then either post it somewhere and then from there, it sounds like you hand it off to someone else. And that’s depends on what it is. Is it going out publicly? Is it going to be archived? So, what’s that end process like when it comes to your nav screen through 700 images because you just are done with the event? You have to sit down, you have to go through, what happens next?

Josh Valcarcel: One of the more unique aspects of working as a photographer here is, we have a photo lab that basically edits in tones all our images. And so, we do the initial screening. We crop and we kind of choose which images from the entire shoot are worth putting forward. And then we have an entire photo lab team that goes forth. And then we’ll color balance and make everything look great. Hundreds of images that we don’t have to process it, we could just go out and keep shooting, multiple shoots per day, if we have to. I can’t really speak to anything beyond that. I know it gets archived, I know it’s available for you know, if it’s not restricted for any specific reason. It’s available to those on site. But I can speak to how it’s chosen to be released publicly. If anything, I think you could [laughter].

Host: No. That’s true. Yeah, we have a task where every you know, every once in a while, we’ll have to go through either images coming from station or images of events that we know are happening. And then you pick you know, you go down from 700. And you go down to I don’t know, let’s say 100. And then from that 100, we choose three. And then that’s kind of how it goes out to the public. Is you have chosen the best of the imagery that you are ready to archive or put wherever. But it’s up to us to then post those three. Because we’ve already discussed, I mean, we’re talking thousands of images a day. I mean, you can’t post all of that. So, it would just be, you wouldn’t be able to find what you wanted. It wouldn’t be very useful to anyone. So, making sure that we screen that is something that’s really important.

Robert Markowitz: And social media I think is nice to the photographers nowadays, to be able to actually, you know, see our imagery out there on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, wherever NASA decides to post them. Versus back in the day where, you know, some, you know, maybe ten years later, you might see your photo appear in some magazine or book or something similar. So now we see things a lot more frequently posted online. And it’s pretty rewarding to have your pictures out there.

Host: Yeah. Do you find that there’s value in — seeing that in maybe a certain amount of inspiration that comes from people looking at this imagery? Because, you know, one thing that I think NASA is super good at when it comes to even, government agency, but just a business is we have some of the best imagery. You just can’t beat it. And you’re talking about being a fly on the wall and taking a picture of some training. Yeah, maybe it’s just the day, “OK, I got to go capture this training.” But to some it is something that could possibly define a career path.

Josh Valcarcel: I mean, think about all the images we’ve seen throughout our lives about human space travel. We get to add to the iconography of that going forward. That’s so huge. You just don’t know what picture is going to resonate with somebody and create an impact. It could be anything.

Host: James, do you have some moments, some training, some event that you have captured that was just so — that stuck with you?

James Blair: I was fortunate enough to be on a helicopter during EFT-1, Orion’s EFT-1, where the capsule was coming back in during re-entry. And I was on a Blackhawk helicopter — no excuse me, not Blackhawk, Seahawk, a Navy Seahawk helicopter. And there had been so much training, so much preparation for just this one moment. And the hardest thing, my biggest fear was being able to spot it. It’s just like a needle, just a pinhead up in the sky. And I just saw this glimmer in the sky. And I just, I have, I was using an 800-millimeter lens, and I just, I grabbed on to it. And I was just shocked that I found it and so early up in its re-entry and followed it all the way down. And that was probably one of my most memorable moments. I was probably one of the closest people to the capsule as it re-entered. And it was a great experience that you know, Josh has been in the Navy, but I’d never been on a navy ship. And so, we had travelled to — it was out in the Pacific where we covered the re-entry. And we floated out on a navy ship. And that was a great experience too. So —

Host: Yeah, just being on the ship is unique in and of itself. But this is EFT-1. This is the test mission of Orion. It was going super far away from Earth. And then it was the test, one of the parts of the test was to come screaming through the atmosphere at 25,000 miles per hour. So, the fact that you were able to find this little tiny dot coming from almost — it was this lunar space. It was it was kind of near the Moon coming through in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. That’s just I mean, that’s a moment that you know, you can plan for it. But I mean, anything could happen. You can have clouds. You can have clouds. You can be facing the wrong direction. The helicopter pilot could be making a hard bank and then next thing you know, you lose it.

James Blair: Yeah, that was all in the training. I mean, it was, everything happened the way it was supposed to happen. It was, we were in the right spot, the right time. The capsule landed on the right spot and all the training paid off. So that was a great feeling.

Host: Yeah. Robert, do you have something like that where you just have something that you have to capture right in the moment. And that’s it. You just have that one shot because it’s not like you can say, “Alright, Orion, sorry, I missed it. Could you go back through the atmosphere and then come back in. Just tell me where you are. So, I can get you next time.”

Robert Markowitz: Yeah, so when you tell a lot of people that you’re a NASA photographer, usually the question you get is OK, what’s the coolest thing you’ve ever photographed?

Host: Yeah.

Robert Markowitz: And so that’s definitely, I have. I usually have a top three. But, for again, being the toughest shoot and kind of, you know, you have one time only to pull it off. I was fortunate enough to fly back seat when they retired the space shuttles and they took all the space shuttles to various science museums across the country. And so, before they landed the shuttles in the various cities, they did fly arounds of each city. And so, we chased the shuttle on back of the 747 and captured it flying over Washington, D.C., New York City for one on the Intrepid so I was in the backseat capturing those photos, as it was going across the Mall in Washington D.C. and down the Hudson and in New York City. And you only had one chance. And so, a lot of times I could specifically remember sitting in the backseat being alongside, taking the pictures out the window of the canopy of the T-38 and literally thinking I should pinch myself. Because this is such an abnormal, unusual place to be taking pictures like this. But those are actually some of the, you know, most memorable photographs I think I’ve, you know, captured almost since I’ve been out here for 30 years. You know, that iconic shot with the shuttle going down the Mall in Washington D.C. We can see the National Monument in the capital from one end to the other. In New York City, I captured a really neat shot. And I remember, you know, kind of looking through my viewfinder is, you know, we’re flying the path. And I can see the image appearing in my viewfinder and I’m like, OK, in a second, it’s going to it’s going to come, it’s going to come. And the shuttle crosses the park and get the whole downtown area in the background. And it was just a really beautiful shot that I captured.

Host: It was a moment that you knew was coming too right? Because you had to study the flight plan. You knew it was in the background. You knew your moments —

Robert Markowitz: But as James said, there’s a lot of things that can go wrong with that. But it all came together. And I was really pleased with the way that image turned out.

Host: I’d be half tempted to just put the camera down and just witness it, yeah, yeah. I have trouble with that too, because I want to take photos of a lot of parts of my life like a lot of people do now and post them on social media. But sometimes, I just you know, I want to take the camera down and just kind of soak it all in. But this is a key moment for not just you but is for many people. Because a lot of people have worked on these shuttles. They’ve captured the hearts and minds of all these people. I mean, there were crowds coming out, right? I’ve remember I was one of my first actually, my very first internship was to work the Endeavour flyover for Houston. And so, I was over at Ellington Field. And I was working education activities handing out little, you know, having people try on gloves and stuff. But I saw it. I got to capture it from you know, not as well, as good of a view as you guys. But I had my phone going across Ellington Field, I think it did two passes or something. Just a wonderful moment and just to be a part of that was significant. Josh, what about you? Favorite moment.

Josh Valcarcel: Favorite moment? I have not been pressed that much yet. I’ve been kind of training going in that direction. I would say my favorite thing that I’ve had the opportunity to shoot here so far was the Wilderness Survival Training with a new group of astronaut candidates that are now astronauts, they recently graduated. That was just the most meaningful thing I’ve ever gotten the chance to do. And I went with them to Maine, spent a week with them, basically camping, just documenting their training. And it’s an important moment for them. It’s early on in their training. So, they’re getting to kind of know each other. And I felt like, I kind of get to know them too and become part of the community here. Which is a really special thing to be a part of, is a very familiar atmosphere. You know, it feels really tight knit. And that was my introduction basically into the job and into the culture and into the world of like, what we’re doing and why and who’s going, and it was just very cool.

Host: Yeah, I love — you have such a unique perspective as a NASA photographer. And I’m going back to when you were talking about the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer Spacewalk training, and you got to see Andrew Morgan and Luca Parmitano train for doing this thing. Then you saw it in space, and you were with all these different teams. That’s I think something that’s very unique to a NASA photographer is because, you know, an engineer, you know, you might be an engineer for just the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, high fidelity mock-up that goes on the [Active Response Gravity Offload System] ARGOS. And that’s it. And that’s what you do. And maybe, you know, you don’t get as much time with the divers at the NBL. You don’t get much time with the crew trainers over here. But you’re seeing all parts of it. You’re seeing all parts of it. And you’re a part of that journey. What is it you try to capture in the photography to try to tell that story because it’s a story that I think is maybe unique, but it’s necessary? It is the journey from start to finish.

Josh Valcarcel: I like to think of myself as a time traveler that is from the future and I’m back in time and I’m documenting history. So that’s the overarching sort of theme that I work with. But generally, I try to meet people in events where they’re at. So, I just try and see it as a moment in time, like a corner of eternity. And this is only going to happen once. And then tomorrow will be another thing. But each person has their part to play and is truly invested in it. So, if there’s a moment where you can see it on their face, you try and capture it. If they’re collaborating with each other, and you’re trying to solve a problem, and it’s the middle of happening, you try and capture that too. There’s so many ways that this experience can kind of manifest itself in front of you. And you just try and be in tune and open to how that can come about with wherever you happen to be standing or wherever you could be standing.

Host: Yeah. Robert, you probably have more of an understanding along these lines of — and I’ve heard this term quite a bit, just being at NASA these past few years, the NASA family. But you see it a little bit more from all like, again, all of these different disciplines, all these different areas that most people at NASA don’t get to explore all the time. We just not in all the buildings. We’re not we’re not seeing all the people and all the unique — you probably have a better aspect than most, a better perspective of seeing all of what is the NASA family. And all the different subcultures and what brings it together as one unique family. What have you seen just over these past 30 years? To really define that.

Robert Markowitz: Well, the thing that comes to mind the most is when you go out and you photograph or you talk to different people, a lot of people will say, “You guys probably have the coolest job out here except for the astronauts,” which is pretty much true. Because, you know, we’re at everything. So, you know, you think about the astronauts training, like Josh said, you know, we were pretty much all involved in a lot of the AMS training. And, literally, you know, you feel like you can, you know, of course, we can’t do their jobs, but you almost you become very familiar with what they’re doing.

Host: Yeah, you want to point to a boat and be like, that one right there —

Robert Markowitz: When you see, you know, it on TV and in mission control of what they’re doing, you have experienced it, you know. Underwater when we used to do the documentation underwater, and, you know, they’re assembling the pieces of the space station. We were there as they were practicing these things. And repairing the Hubble Space Telescope. But the family is definitely true. Being out here for so many years, whether you see people here or outside of work or on travel, in airports. It’s just one big family. I remember one time I got on a Southwest flight and ran into a retired astronaut that was flying for Southwest. And you know, he was greeting passengers coming onboard and was like, “Hey, how you doing? Hey long time no see.” So, you just run out, you know, you run into people, you know, in the grocery stores, at restaurants, you know, the astronauts, the flight directors, wherever it may be. And you know, it definitely does feel like a family culture out here.

Host: Wow. So, James, you talked about this era of — you’ve talked about social media. You talked about this change from taking so many pictures and doing it in a different style, now having this ability to share more. What do you find is important about that and the value of that? And what kind of personal aspects do you bring to sharing these photos?

James Blair: I see our job as being the eyes for the public. We see, like you say, we see things that we’ve been to events that others just don’t have access to. And so, it’s my job to document it in a way that creates excitement and shows how exciting the space program is. So, it’s, yeah, I take it as a privilege. And I try to create excitement with my imagery.

Host: Yeah. And I think you’re all doing such a good job. I mean, I’ve had the pleasure to work with each one of you in multiple different capacities and just see, you know, you just walking around. You’re there. I’m on a tour and you’re there. I’m on mission control and you’re there. You know it and even when I’m not there, you’re there. [laughter] Like, we really appreciate what you do. And it’s very significant to not just the NASA family, but to those that want to be engaged with the NASA family. So, Robert Markowitz, James Blair, Josh Valcarcel, I really appreciate your time for coming on Houston, We Have a Podcast and sharing this unique perspective that no one else has. Appreciate the time.

James Blair: Thank you.

Robert Markowitz: Thank you.

Josh Valcarcel: Thank you for the opportunity.

[ Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. Really fascinating conversation we had with these guys today on what it’s like to be a NASA photographer. I hope by now you have a deep appreciation for what they do. And if you’re like me, you’re also kind of jealous. We have a lot of episodes of Houston, We Have a Podcast. You can listen to any one of them in no particular order at NASA.gov/podcasts. You can find a lot of other NASA podcasts there on any topic you’re interested in. If you want to follow us on social media, we’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. If you have a question for us or you’d like to submit an idea or a topic, use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform. And just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston, We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on February 4th, 2020. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Norah Moran, Belinda Pulido, Jennifer Hernandez, Mark Sowa and Kelly Humphries. Thanks again to James Blair, Robert Markowitz and Josh Valcarcel for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and some feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us how we did. We’ll be back next week.