On Aug. 30, 2019, when amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov gazed upward with his homemade telescope, he spotted an object moving in an unusual direction. Now called 2I/Borisov, this runaway point of light turned out to be the first confirmed comet to enter our solar system from some unknown place beyond our Sun’s influence. Astronomers everywhere rushed to take a look with some of the most powerful instruments in the world, hoping to learn as much as they could about the mysterious visitor.

Now, thanks to observations with NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers have figured out that 2I/Borisov has an unusual composition. Specifically, it has a higher concentration of carbon monoxide than any comet seen at a similar distance; that is, within about 200 million miles (300 million kilometers) of the Sun.

This suggests to scientists that the comet could have formed around a red dwarf — a smaller, fainter type of star than the Sun — though other kinds of stars are possible. Another idea is that 2I/Borisov could be a carbon monoxide-rich fragment of a small planet.

What is an interstellar comet?

Comets are snowballs of ice, dust and frozen gas. When totally frozen (or “inactive”), they’re approximately the diameter of a small town, but when heated by the Sun their tails can extend for millions of miles. 2I/Borisov is about the length of nine football fields, or 0.61 miles (0.98 kilometers), making it relatively small. The new results on the comet’s composition are published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

All comets form in the primordial disk of material that encircles a young star, preserving remnants of a planetary system’s ancient past. Comets from our own solar neighborhood reveal the history of materials, including water, that made Earth the planet we know today, as well as our other planetary neighbors. An interstellar comet, on the other hand, is a chemical ambassador from an entirely different star system — containing a treasure trove of clues to worlds too far to reach with modern technology.

“With an interstellar comet passing through our own solar system, it’s like we get a sample of a planet orbiting another star showing up in our own backyard,” said John Noonan of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, Tucson, and a member of the Hubble research team led by Dennis Bodewits of Auburn University in Alabama.

What scientists found

Bodewits and colleagues used Hubble to look at 2I/Borisov from Dec. 11, 2019 to Jan. 13, 2020. Separately, a team of international scientists led by Martin Cordiner and Stefanie Milam at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, studied the comet on December 15 and 16, 2019, with ALMA, an array of radio telescopes at an altitude of 16,570 feet (5,050 meters) in northern Chile. Radio telescopes are especially useful for looking at cold, low-energy gas in objects like comets.

Results from both Hubble and ALMA estimate that 2I/Borisov’s carbon monoxide concentration is higher than that of the average solar system comet.

Where did it come from?

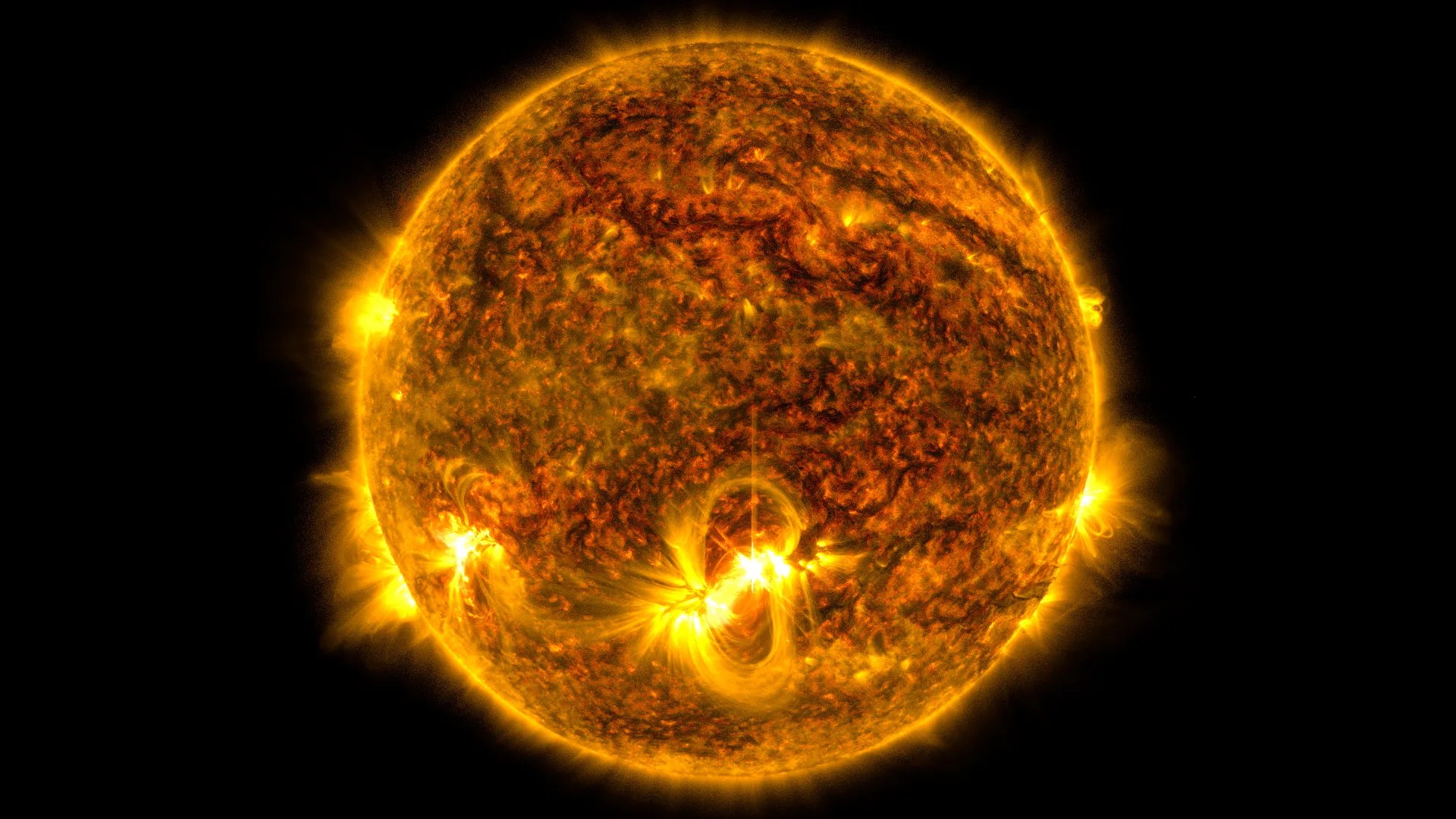

A high carbon-monoxide-to-water ratio suggests that the comet has traveled from a very cold place — as cold as the area where Pluto is in relation to our Sun, called the Kuiper Belt. The group using Hubble additionally theorizes 2I/Borisov may have originated around the most common type of star in the Milky Way: a red dwarf. Red dwarfs are much smaller and dimmer than the Sun, so the planet-forming material around them would be colder than the building blocks of our solar system.

“These stars have exactly the low temperatures and luminosities where a comet could form with the type of composition found in comet 2I/Borisov,” said Noonan.

Scientists using ALMA say it’s possible that 2I/Borisov could be a fragment of a dwarf planet that had a lot of carbon monoxide near its surface, regardless of which type of star it came from. “If that object collided with another, then the carbon monoxide-rich fragments could be released into space,” said Cordiner.

But 2I/Borisov may have simply formed as a comet with a high concentration of carbon monoxide, the ALMA team points out. Alternatively, it may have an unusually thick outer layer that insulates frozen gases like hydrogen cyanide and water. As the more volatile carbon monoxide evaporates or “outgasses,” it may appear more abundant than other cometary gases. 2I/Borisov’s unusual properties may also suggest a wider diversity of carbon monoxide in comets in our own solar system than previously thought.

“Whatever the answer is, 2I/Borisov opens up a whole new can of worms for cometary science,” says Milam, one of the scientists using ALMA.

In our own solar system, there are two places where most comets reside: The Kuiper Belt, an area that includes Pluto; and the Oort Cloud, which is much farther away. All of these comets likely formed closer to the Sun, but may have been booted outward by the erratic movements of Jupiter and Saturn billions of years ago. These giant planets, because of their immense gravity, could have even sent comets flying toward other stars, escaping the influence of the Sun’s gravity altogether.

Given this history, scientists using Hubble theorize that a massive planet in a red dwarf system, in an environment with frozen carbon monoxide, may have punted 2I/Borisov our way.

“If a Jupiter-sized planet migrates inward, it could kick out a lot of these comets,” Bodewits said.

The team using ALMA agrees that a young moving planet likely sent the comet on its way. “Then, after a cold, lonely voyage, 2I/Borisov made its close encounter with our solar system and started outgassing and showing us what it’s got inside,” Cordiner says.

More to come

Credits: NASA/ALMA

2I/Borisov is only the second object astronomers have detected that definitely came from a different star system. The first was ‘Oumuamua, discovered in October 2017, that whizzed by too quickly for scientists to pin down its chemistry. Whether it too is a comet, an asteroid, or something else — we may never know.

2I/Borisov is continuing on its path through the solar system, and will eventually head out. As more advanced telescopes and other instruments turn on and gaze out in the coming years, astronomers expect to find more interstellar objects, though they will still be rare.

“Our solar system is so tiny compared to the distances between star systems,” Cordiner says. “For an interstellar comet to come in and hit the bullseye like Borisov did is incredible.”

ALMA is a partnership of ESO (representing its Member States), NSF (USA) and NINS (Japan), together with NRC (Canada), MOST and ASIAA (Taiwan), and KASI (South Korea), in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. The Joint ALMA Observatory is operated by ESO, AUI/NRAO and NAOJ.

Written by Elizabeth Landau

NASA Headquarters