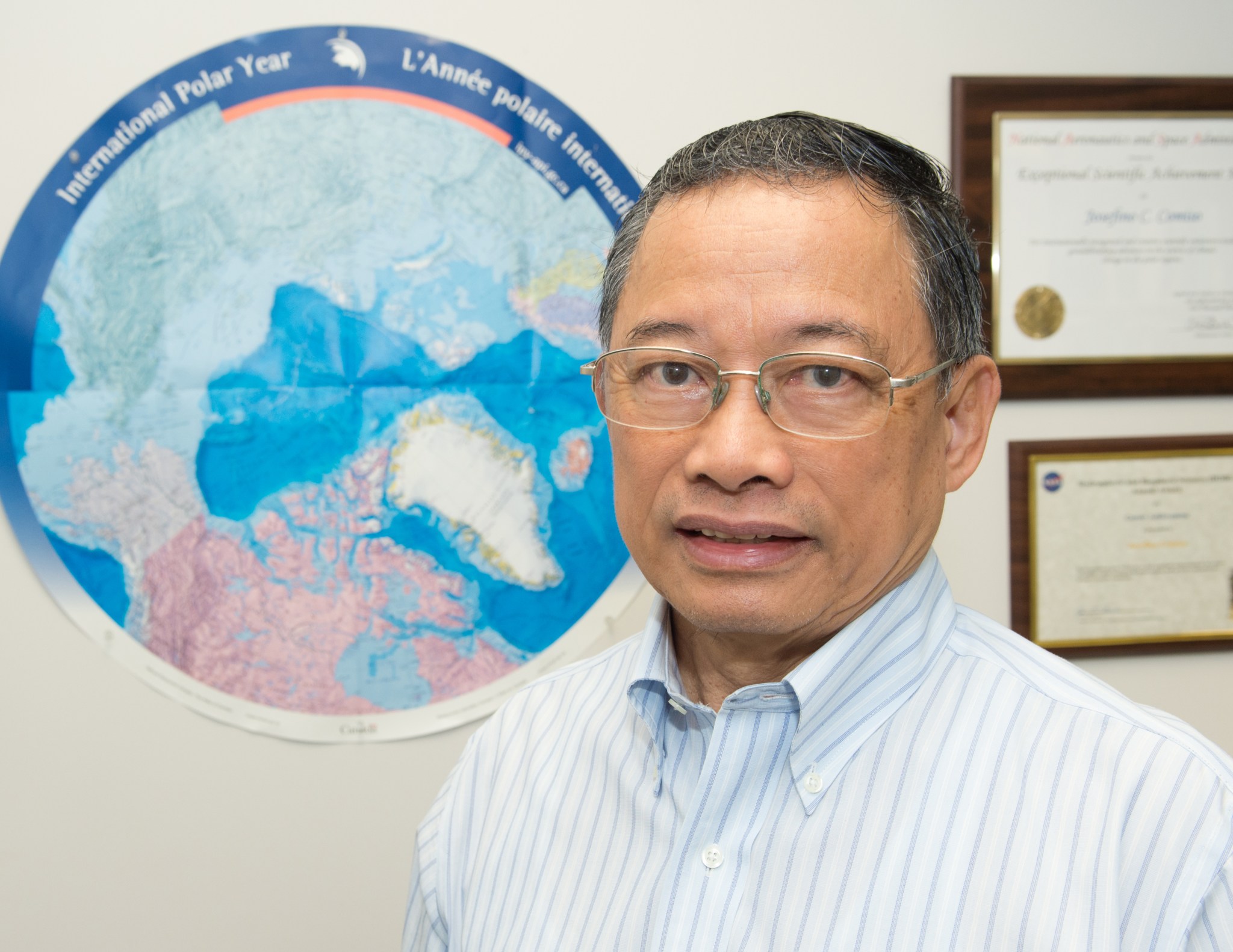

Name: Josefino C. Comiso

Title: Senior research scientist

Formal Job Classification: Physical scientist

Organization: Code 615, Cryospheric Sciences, Earth Sciences Division, Science Directorate

Climate change, trends in sea ice and wintering in Antarctica.

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I study global climate and environmental changes as observed from space. In particular, I develop algorithms for satellite sensors and polar parameters. Using these algorithms, I develop data sets of historical satellite data, analyze the data and assess spatial and temporal changes that may be associated with climate change.

I was one of the first to use satellite data to study sea ice change. In 2002, I reported that the sea ice cover in the Arctic at the end of the summer was declining rapidly. The following year, I observed that the temperature in the Arctic was rising three times faster than it was globally primarily due to ice albedo feedback. The feedback means that since the ice has high reflectivity and the ocean has low reflectivity, when the ice retreats, there is more ocean exposed to solar energy causing more warming. More warming means more melting which causes more ice retreat. This goes on in a loop where everything is amplified.

Why do you do fieldwork?

I do fieldwork to validate my algorithm studies. I have been to Antarctica, the Arctic, Alaska and Greenland.

Tell us about being among the first group of scientists on a winter cruise in Antarctica to conduct fieldwork.

In 1986, I was a member of the first winter cruise in the Antarctic on board the German icebreaker, called the RV Polarstern. Although working in the Antarctic environment is difficult because of extremely harsh conditions, scientists are able to relax and recover from their daily routine because the ship was well-equipped and had a sauna, swimming pool, music room and two bars. The ship stopped periodically for ice and oceanographic measurements at which time I would make measurements using a set of microwave radiometers with frequencies similar to those on board satellites. I also studied ice characteristics, including thickness and temperature of both snow cover and sea ice.

Why did you go on a winter cruise to the Antarctic?

A key goal was to gain understanding of the processes that caused the formation of the large Weddell Polynya that was observed from space by Nimbus-5 ESMR in 1974, 1975 and 1976. A polynya is a body of water surrounded by sea ice and the Weddell Polynya was a great mystery because of its size (larger than the area of California) and persistence (does not freeze during winter in the Southern Hemisphere). The cruise also provided the first opportunity for marine and physical oceanographers to fill in extensive knowledge gaps about the Antarctic region in winter.

Describe your fieldwork in the Arctic.

I was the chief scientist in a few aircraft validation programs the most interesting of which was the one that flew over a nuclear submarine in the Arctic region in May 1987. Our results showed unambiguously that the thickness of the sea ice cover can be measured from space using freeboard information and laser technology.

How does it feel to be a pioneer in studying sea ice?

It feels great to be among the pioneers in the study of the large scale distribution and variability of sea ice from space. We are lucky that NASA did research and development on passive microwave sensors that allowed us to study the global characteristics of sea ice continuously. I was also lucky to have developed the Bootstrap Algorithm for sea ice that is currently one of the standard algorithms used for generating ice climate data sets.

What is your educational background?

I received a Bachelor of Science degree in physics from the University of the Philippines, a Master of Science degree in physics from Florida State University and a doctorate in elementary particle physics from the University of California at Los Angeles. Also, I was a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Virginia and did research at the synchrocyclotron facility at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, and the Los Alamos Meson Physics Facility in New Mexico.

Why did you become interested in studying sea ice?

While looking for a permanent job, I was informed that NASA had a robust program on climate change and was looking for scientists to work in the field. I became interested and started as a senior analyst at Computer Sciences Corporation, which was then providing research support for NASA Goddard programs. I was asked to work on a task that involved analysis of satellite passive microwave data and the development of a sea ice geophysical data set from these data. I must have done some useful work, because after a few months I was encouraged to join NASA as a physical scientist.

It took another year to become a NASA employee and during my first day of work I was asked by the associate director of Earth Sciences why a person like me who came originally from the tropics would be interested in sea ice. I told him about the relevance of sea ice to climate change studies. I never thought that after 30 years I would still be at NASA and be able to report that there are dramatic changes in the Arctic and that sea ice is providing one of the biggest signals of climate change.

Do you return to the Philippines?

My wife and I still have family, a house and properties in the Philippines although I have been at Goddard for more than 35 years. Previously, we returned every two to five years but during the last several years, I used my annual leave and returned more often as a participant of the Balik (returning) Scientist Program (BSP). BSP is a government program to encourage scientists with Filipino backgrounds to return and share their expertise with students, other scientists and interested professionals. While there, I lectured at universities and other institutions about climate change and applications of satellite remote sensing.

Have you had students from the Philippines?

During one of my lectures at the University of the Philippines, a student asked me to be her doctoral adviser. She came to Goddard to do research for her degree and is now a college teacher in Maryland.

I recently had three postdoctoral fellows from the Philippines. One studied cloud cover in the Arctic and published two papers. The other used Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) data to study vegetation and published two papers with a third in review. The third also studied MODIS and completed a paper on crop studies.

What would be the effect of summer ice melt?

I’ve found that the Arctic perennial ice cover, the ice that survives at the end of the summer, is declining at a rate of 11 percent per decade. For about 1,500 years, the perennial ice has been observed, but if the current decline rate continues we would have an ice-free Arctic in summer within this century – it will be the first such occurrence in modern history.

There would be more warming in the Arctic region and more melt in land ice that would cause sea level rise. There would be ecological changes, like primary productivity, that would spread to other parts of the world. The highest plankton (or chlorophyll) concentration has been near the polar regions in part because of sea ice. Melted sea ice water forms a stable water layer that is exposed to abundant sunlight and becomes a platform for enhanced photosynthesis and hence high productivity. The loss of the ice cover would mean reduced plankton concentration. Since the plankton is at the bottom of the food chain marine life would be affected and fishery production would be reduced.

Is the summer ice in the Antarctic also melting rapidly?

What appears in the Antarctic seems to be the opposite of what we see in the Arctic. The ice is observed to be receding in the Arctic, but expanding in the Antarctic. Some interpret this to mean that there is no climate change.

However, the environmental conditions are very different. In the Arctic, the sea ice covers the North Pole and the Arctic Basin. It is really cold and ice on average is about three meters (about 10 feet) thick. In the Antarctic, the continent is huge and the sea ice surrounds this big continent. The sea ice is located at a higher latitude and generally warmer and thinner but more expansive because there is no land boundary to the north.

Observed distributions of global temperature are also not uniform and show that the trends in temperature in the Northern Hemisphere are much more positive than the trends in the Southern Hemisphere.

Can we still save the sea ice cover in the Arctic?

Modeling studies indicate that if we keep the level of greenhouse gases constant from now on, we will be able to keep the temperature from reaching more undesirable levels. The sea ice cover in the summer could be salvaged.

What was a highlight of your climate change studies?

In 2010, I was selected as one of the coordinating lead authors of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2014 report which is regarded as one of the most authoritative documents on climate change. An earlier version of the report, for which I was a contributing author, won half of the Nobel Prize in 2007.

Who is your science hero?

My science hero is the late Dr. Richard Feynman, who won the Nobel Prize in physics for his theory in quantum electrodynamics. I was inspired by his bold, colorful personality and his ability to solve problems quickly and elegantly. His three-volume collection of physics lectures gave me a solid background in basic physics, which I have relied upon throughout my career.

Dr. Feynman also has a NASA connection. He was the one who proved that the cause of the space shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986 was frozen o-rings.

OF NOTE: Honors and Awards:

- NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal, 2013

- NASA Goddard Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences Career Achievement Award, 2014

- NASA Group Achievement Awards (1982 and 2003)

- Outstanding Achievement in Science in 2008 (Pan Oceanic Remote Sensing Conference)

- Distinguished Achievement Award in Science and Engineering (2013, by the UP Alumni Association)

- Fellow of the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (2006)

- Most Distinguished Alumnus of the University of the Philippines (2007, UPAAA)

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.