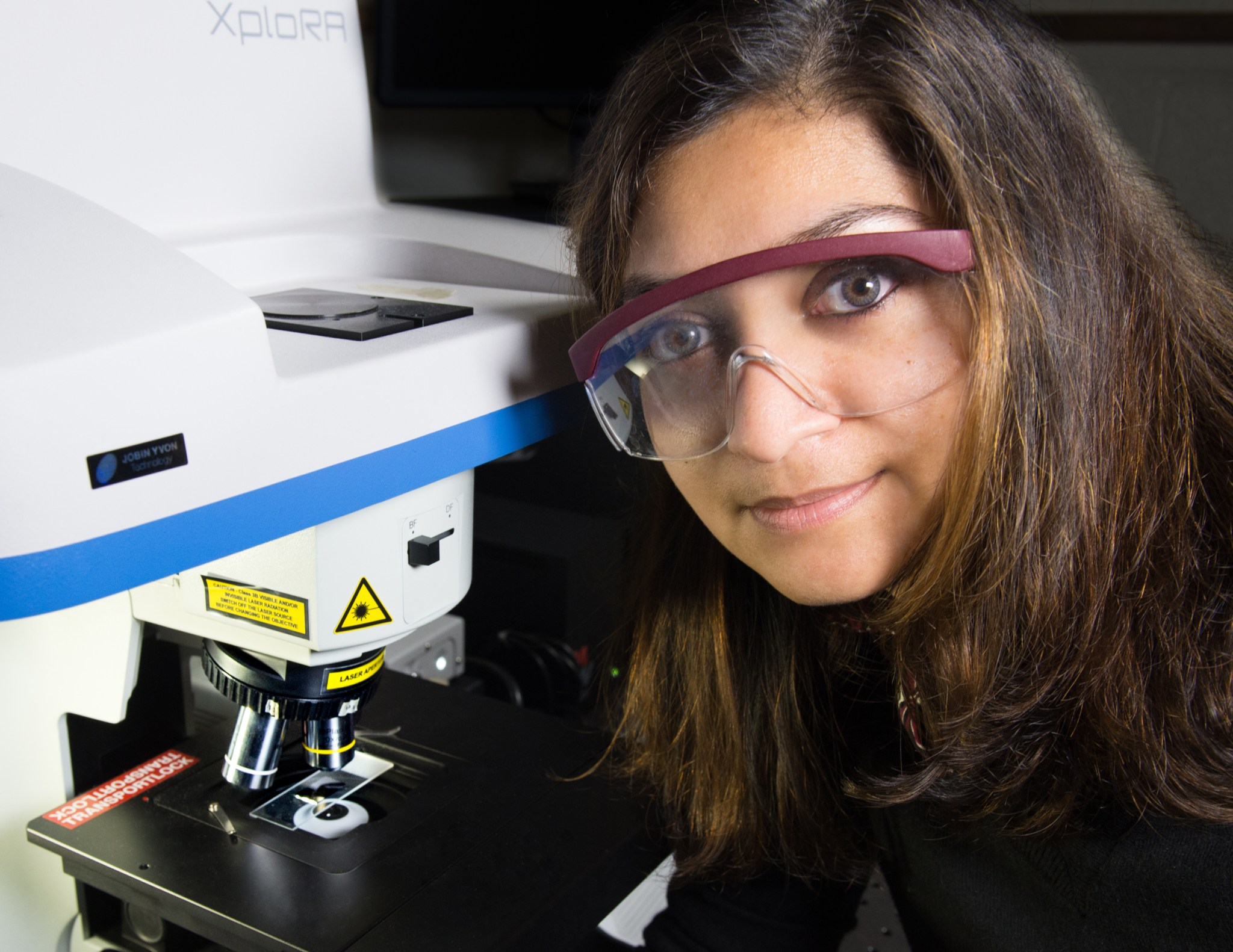

Name: Mahmooda Sultana

Title: Associate Branch Head, Instrument and Payload Systems Engineering Branch, Engineering Directorate

Formal Job Classification: Aerospace engineer

Organization: Code 592, Instrument and Payload Systems Engineering Branch, Engineering Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

My current role allows me to contribute to Goddard’s mission in many different ways. I help develop new instruments using cutting-edge technologies that enable new science missions. I also help provide supervisory oversight over the instrument systems engineering work on various flight missions and provide branch management support

Why did you become an engineer, overcoming cultural and family expectations?

I grew up in Bangladesh. My father was a supervisory civil engineer for the government. He built dams and barrages that controlled the water flow from the Himalayas and India to prevent flooding. He used to take us to the field and explain how the different components work. He let us play in the control room. That definitely got me interested in understanding how different devices worked.

We lived in a community where all the government engineers lived together. All our neighbors were engineers. There was not a single woman engineer that I remember in that community of hundreds. My brain automatically presumed that women did not grow up to become engineers.

My great uncle was a physicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. I loved hearing about his work. Growing up, I wanted to be a mathematician. I loved math, physics and chemistry. I wanted to be a mathematician or a scientist and work for NASA.

When I was 14, my family moved to southern California and I started in 10th grade.

When it came time to apply to colleges, I applied as a double major in math and physics. However, my high school chemistry teacher was very disappointed hearing about my intentions because he wanted me to major in chemistry. He convinced me to major in chemical engineering so that I could combine math, physics and chemistry.

My parents did not want me to pursue math and physics either. They expected me to go to medical school above all or else go to engineering school. Their expectations had to do with cultural conceptions. In south Asia, people do not value science as much as they value engineering. The best students in South Asia typically go into engineering or into medicine. Sciences and arts are usually second choices. I thought I could go to college for chemical engineering and then go on to medical school. My parents really liked that plan. That is how I got into chemical engineering. But, once I was in it, I loved the discipline.

I got a bachelor’s of science in chemical engineering, with a minor in math, from the University of Southern California.

After that, I went to Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a Ph.D. in chemical engineering on a fellowship. By that time, I felt that chemical engineering seemed to offer the most options for future work. My parents were very disappointed that I did not become a medical doctor.

How did you come to Goddard?

In my final year at MIT, I was thinking about what I wanted to do next. I enjoyed teaching, but did not want to pursue a tenured professorship. I had several lucrative offers from research labs and industry. Even though I dreamed of working for NASA as a child, NASA was not in my mind during my graduate school years.

I went to a career fair at MIT in my final year. I had one resume left after distributing my resumes to the companies and research labs I was considering at the time. I saw the NASA Goddard booth and suddenly remembered how excited I was about working for NASA growing up. So, I decided to give my last resume to the then-associate branch head of the detectors branch, Thomas Stevenson. At first, he said that the detectors branch did not have a lot of opportunities for chemical engineers. When I described my multidisciplinary thesis work to him on micro electric mechanical devices, he was immediately interested. We had a follow up phone interview and I got a job at Goddard. So, it was quite serendipitous.

Even though some of my other offers were for twice the salary, I came to Goddard in 2010. My mother was very happy that I was going to work for NASA.

Prior to your current work, what was one of your most interesting projects?

Initially, I was part of a team that worked on the microshutter array for the James Webb Space Telescope. This array includes hundreds of little windows that can open or close to let light into the detector. The microshutter array was one of the most interesting projects I have worked on.

Please tell us about some of your inventions involving nanotechnology.

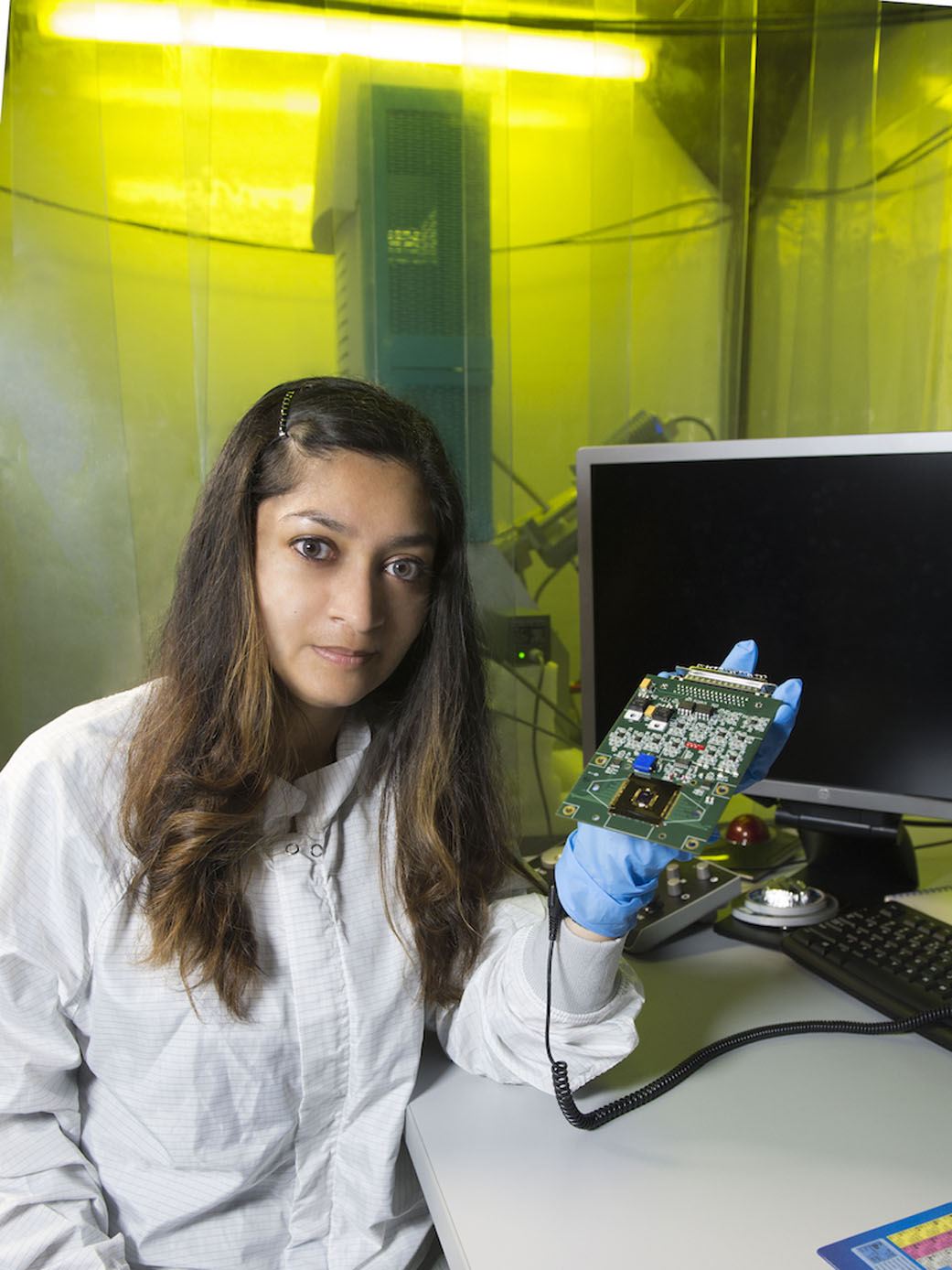

I hold a few patents and have additional patents pending in nanotechnology. I have developed several new nanotechnology-based instruments for use on future missions.

One of my inventions is a multifunctional sensor platform, which is an instrument-on-a-chip, by printing a suite of sensors and other components made of nanomaterials on a single substrate. This multifunctional sensor platform will be able to detect key gases needed for the origin of life as we know it, and can be used to explore habitability and life on other planets.

In 2017, I won the Goddard’s Internal Research and Development Innovator of the Year award for some of my work.

What are some of your current innovative projects? Do you collaborate with outside facilities on them?

I already mentioned about the multifunctional sensor platform. I am also developing a multispectral imager using quantum dots. Quantum dots are nanometer-sized particles of semiconductors that have interesting optical properties.

I collaborate with a number of other organizations, including MIT, Northeastern University, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and LPS on some of my projects.

How does your work support your key value of learning?

Learning has been a big part of my life and contributing to learning means a lot to me. I love the ability to use my brain, to come up with interesting ideas that can enable new missions to give us knowledge, and implementing those ideas.

My parents instilled learning as one of my key values. My mom was an avid reader. Our house was full of books of all kinds. Every table, every shelf was filled with books. People used to come to our house to borrow books. My dad on the other hand was mostly interested in math and science books. He used to buy me children’s knowledge series books on math and science.

My parents were quite proud that my work at NASA contributed to scientific knowledge and enabled new missions.

Why do you enjoy outreach? What was one of the most meaningful encounters you had doing outreach?

It is very important to me to change the cultural trends and societal expectations of women. We respond to what we see around us or on television. Growing up, I never saw any women engineers in my community, so I assumed women did not become engineers. I now give talks at high schools and middle schools sharing my journey to serve as an example to the young girls. I want them to know that they can become a scientist or an engineer at NASA too if that is what they would like to be in life. Good examples go a long way to changing our cultural expectations that our young girls respond to growing up.

Last year, I gave a talk at a Baltimore middle school. After my talk, a young girl approached wearing a T-shirt that said “Forget princess, I want to be an astrophysicist.” She took a photo with me, which I treasure. She said, “When I grow up, I want to be just like you. I want to work at NASA.” She made my day!

Is there something surprising about your hobbies outside of work that people do not generally know?

I like playing strategic, math-oriented board games. Goddard has a board gaming club, which is where I met my husband, an astrophysicist who works at Goddard.

Who is your favorite author?

I have many. Growing up, I loved Jules Verne. I still love science fiction and historical fiction. I especially enjoy books by Sir Henry Rider Haggard, who wrote creative adventure stories that later inspired J.R.R. Tolkien.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center