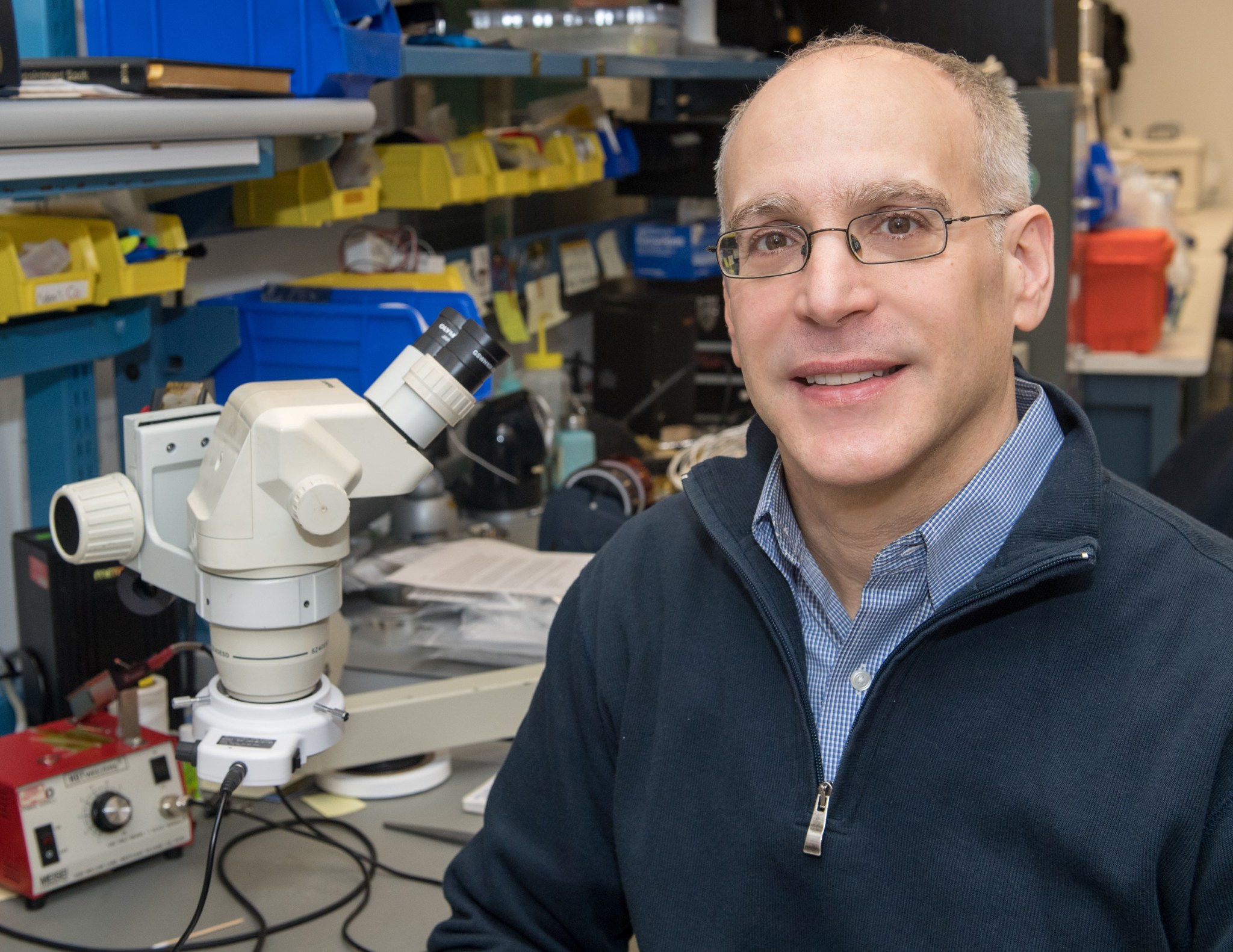

Name: William Yuknis

Title: Branch Head

Formal Job Classification: Computer Engineer

Organization: Code 565, Avionics and Electrical Engineering Branch, Engineering and Technology Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

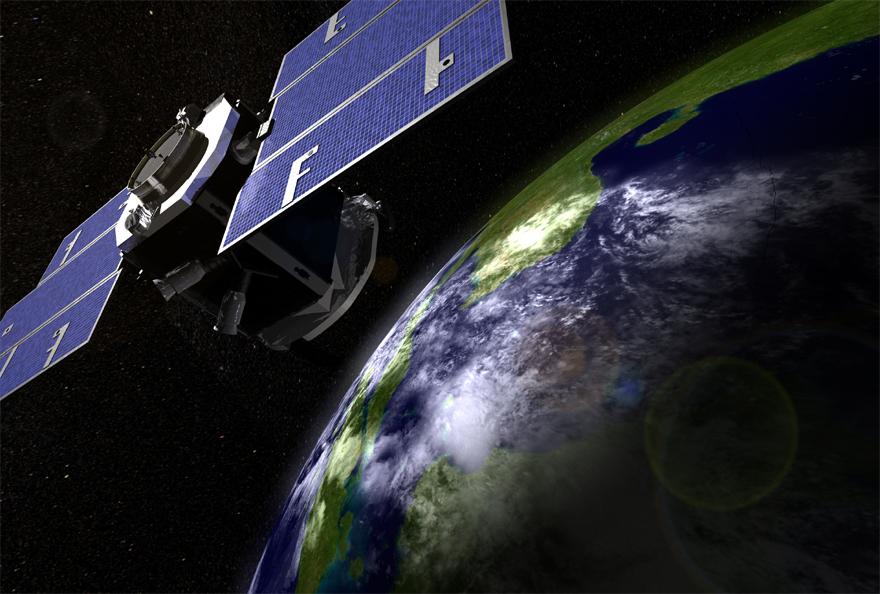

As branch head, I supervise approximately 50 other engineers who perform avionics and electrical engineering functions for Goddard missions. I am the technical authority overseeing the design, construction and testing of these spacecraft and instruments. Every major Goddard mission comes through our office including the James Webb Space Telescope; the Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) Mission; PACE’s Ocean Color Instrument (OCI); and the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST).

You said that you want to talk about your deafness and use your story to inspire other people who are deaf or have other disabilities. Would you please tell us more?

Yes, I would like other people who are deaf or have other disabilities to know all that they can do and become. I also would like them to know that NASA is a welcoming place.

I was not born deaf. At around 16 months of age, my mother noticed that I was no longer responding to sound. No one knew why. When I was about 30 years old, my doctor finally investigated the cause of my deafness and concluded that I have a structural ear anomaly.

I rely on lip reading and, at times, a sign language interpreter. After a while, in a one-on-one setting, I become accustomed to how a person speaks and just lip read. In group settings, it is much easier for me to use a sign interpreter.

How did your parents help you get an education?

I had the perfect scenario because both of my parents were educators. My mother actually had a degree in special education. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was not enacted until I was in college. Before that, we had the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) that enabled children with disabilities to have access to a public education with the help of Individual Education Plans (IEPs).

My mother was instrumental in my early education. She worked closely with the schools to make sure that I had a workable IEP to accommodate my deafness. She made sure that, for example, I sat in front of the class. I can lip read and also speak. Interpreters were not used much then. This worked well enough for my early education.

I went to Rochester Institute of Technology/National Technical Institute for the Deaf (RIT/NTID). I was RIT/NTID’s first deaf person to graduate with a degree in computer engineering. I then went to Johns Hopkins University for a master’s in electrical engineering.

When did you know that you wanted to be an engineer?

As a child, I was very curious. I always loved taking things apart. According to my mother, when I was about 2 years old, I would rip the labels off of soup cans. My mother would frequently have “mystery meals” for dinner.

Eventually, my parents gave me a “secret lab” in the basement. I graduated to taking apart more mechanical items starting with my toys. I later took apart donated items from friends and relatives such as radios and televisions. It was such fun!

How did you come to Goddard?

As a graduation requirement, all RIT students must work one year total as an intern. While I was at RIT, I interned at Goddard during 1992 to 1994, beginning with the Flight Dynamics group and then moving over to the Special Payloads Division. After graduating from RIT in 1994, I began working full-time at Goddard in the Special Payloads Division. I was fortunate enough that Goddard paid for my graduate degree, one of the great benefits of working for Goddard.

How did you evolve from intern to branch head?

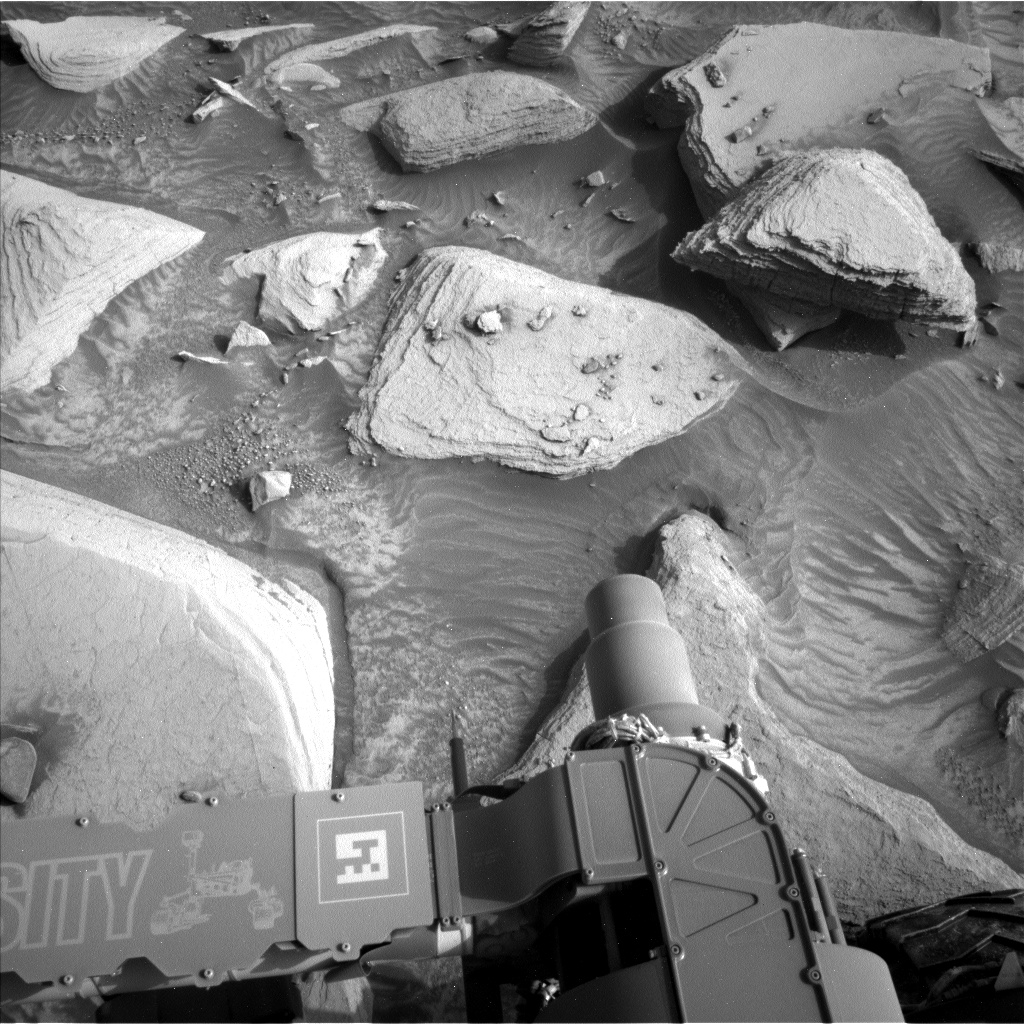

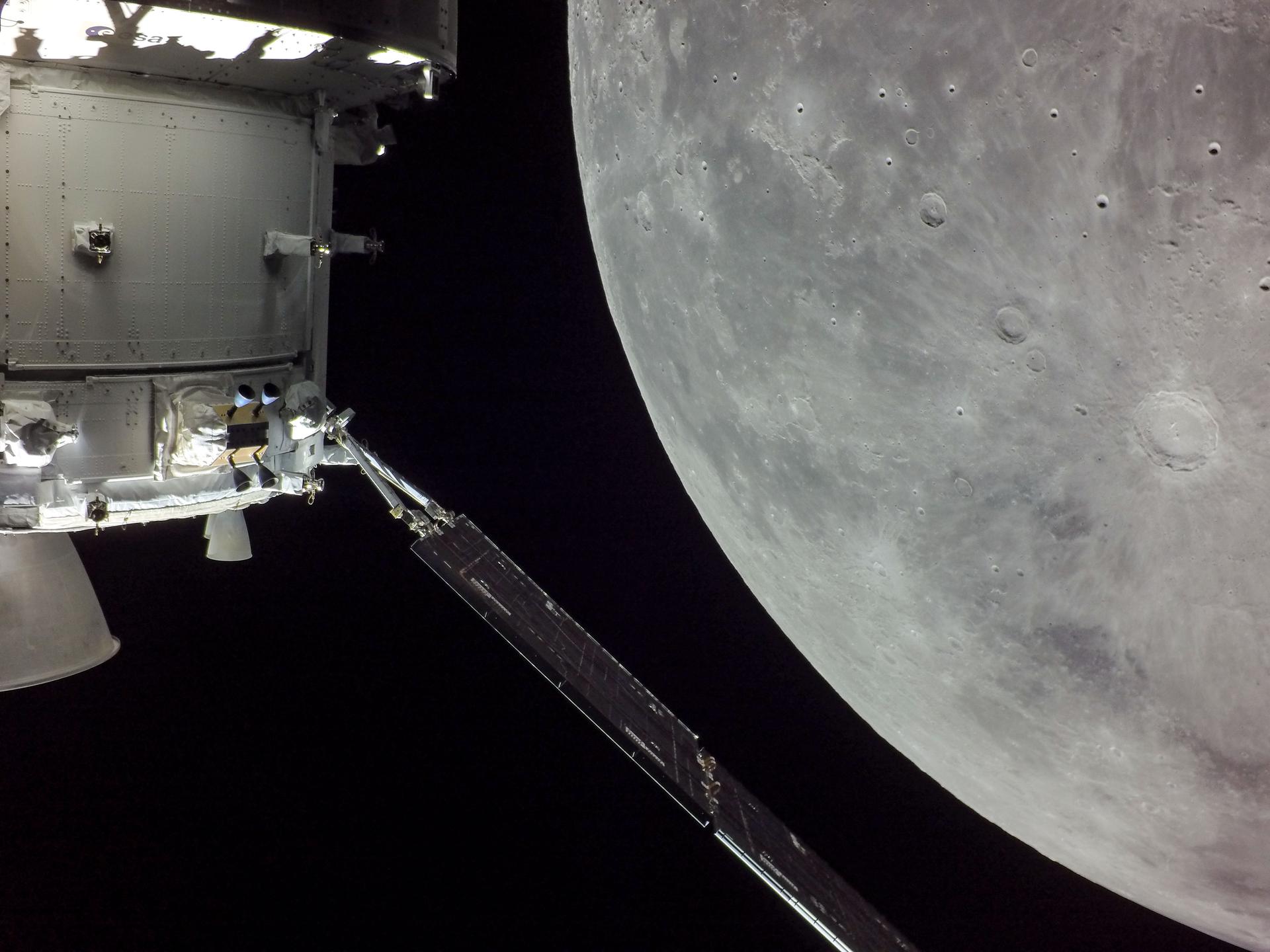

I worked as a computer engineer for a good 17 years with the Flight Data Systems and Radiation Effect Branch. Over the course of those years, I worked on significant missions while looking for leadership opportunities and more responsibility. I was given the job of designing the memory board for the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission, now known as the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory (SWIFT) Mission. The memory board is a key component of the instrument’s brain. Later, I was given the important job of creating the command and data handling unit for the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which is more like the spacecraft’s actual brain.

I was the first deaf NASA engineer to sit at a console in mission operations. I sat at the console in mission operations from LRO’s launch to lunar orbit. I was incredibly proud. I told everyone that I was going to help drive a spacecraft to the Moon. How many people can say that?

Rule No. 1: Nothing flies if it doesn’t work. Rule No. 2: Test before flying to make sure it works. Thankfully, everything I did worked. In fact, both missions are still working 10 years later.

These opportunities, along with several others, greatly expanded my engineering and leadership skills. Both projects allowed me to work with more people and learn how to lead a team.

In 2009, I became associate branch head for the Flight Data Systems and Radiation Effects Branch. Branch management is all about people. One of my goals is to help our people develop to their full potential.

In 2016, I became branch head for my current branch. I continue to try to help our people develop their full potential while also implementing and outlining strategic technical and organizational goals. As branch head, I am “engineering the organization.”

You’ve said you believe that you are NASA’s only deaf branch head. How does that make you feel?

On the one hand, I do not think about it much. I’m good at what I do and I do my job well just like everyone else here. Everyone has a job and I’m doing mine.

But on the other hand, I am thankful that NASA gave me the opportunity to lead a world-class organization within a world-class institution. NASA provided me with educational opportunities. NASA also gave me the tools to do my job. I have worked with people from Goddard’s Assistive Technology Laboratory which provides state of the art assistive technology for those who need it. In addition, I have access to sign language interpreters, a videophone on my desk, and a cell phone for texting and video relay calls.

The people of NASA are great to work with, they are very understanding and patient. Everyone is very inclusive and supportive.

Being a branch head makes me feel extremely proud, proud that I get to work with our esteemed engineers and proud of all that they have accomplished for NASA. The word “awesome” comes to mind. I am humbled to work with these people and feel so fortunate to work here as well.

What message do you want to send to other people with disabilities interested in working at NASA?

Everything starts with a solid education. I am very grateful to my parents who made sure that I got a good education.

I am also grateful to my parents who instilled in me a strong work ethic. Hard work and perseverance pay off. If you keep at it, eventually things will blossom.

I realize that a lot of what I have done is based on my hard work coupled with opportunities given to me by NASA. I was able to progress in my career and lead teams to work on missions of international importance because NASA put their faith in me. NASA gave me goals and, because they believed in me and helped me, I achieved them. NASA is the place to go to do big things.

I just happen to be deaf. There are other types of disabilities. NASA is a wonderfully inclusive environment with a very strong diversity and inclusion program, including for people with disabilities.

Do you have a mentor or are you a mentor? If so, please tell us the most important advice you gave or learned?

Over time, I have been fortunate enough to have had a number of mentors. Mentoring helps people us learn how to navigate the workplace and how things are done.

If I were to say the one most important piece of advice I have received over these 26 years, it would be that details matter. Pay attention to the details, no matter how small.

I have also been a mentor to a number of engineering college students. I always advise them to pay attention to details too.

Is there something surprising about your hobbies outside of work that people do not generally know?

For the past five or so years, I have done triathlons. I am generally decent enough to finish a race in the middle of a pack of people ranging from teenagers to senior citizens. The longest one I have done was 70 miles in Cambridge, Maryland. For my next big birthday, I may do a 140 mile race which will also be in Cambridge.

Who is your favorite author?

I am an avid science fiction reader. My favorite author is Iain Banks, a Scottish writer who passed away a few years ago.

How has your wife’s work helped you?

My wife works at Gallaudet University in their Department of Education. She prepares future teachers and guides them in obtaining their professional teaching certifications.

In November 2018, I was thrilled when my wife was awarded a Fulbright Specialist Grant. As a result of her Fulbright project, the U.S. Department of State sent her to Tunisia to help them improve their education program for the deaf. My wife was in Tunisia for two weeks working with the deaf community to educate children who are deaf. She also had an opportunity to meet with officials from the Tunisian Ministry of Education in order to share broader goals for deaf education.

What is your “six-word memoir”? A six-word memoir describes something in just six words.

Overcoming obstacles one at a time.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center