Name: Gordon L. Bjoraker

Formal Job Classification: Planetary scientist

Organization: Code 693, Planetary Systems Lab, Solar System Exploration Division, Sciences and Exploration Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I am interested in the planets Jupiter and Saturn and Saturn’s biggest moon Titan. I use a combination of spacecraft data and observations from big telescopes in Hawaii. The spacecraft data I use for Saturn comes from the Cassini spacecraft that has been orbiting Saturn since 2004. For Jupiter, I acquire ground-based data for comparison with data from the Juno spacecraft that has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016.

What is your role with Cassini?

I am a co-investigator on the team at Goddard that built a spectrometer on Cassini that works in the thermal infrared. I study the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan and I am also involved in operations. I am part of a team that is responsible for designing observations, which are arranged six months in advance, of Saturn’s and Titan’s atmospheres.

How does Cassini’s end of mission affect your work?

The Cassini mission will end on Sept. 15, 2017, by plunging into Saturn’s atmosphere. We want to avoid accidently crashing into two of Saturn’s moons, Enceladus and Titan, and possibly contaminating them as both may contain the building blocks of life.

We have a huge amount of information from Cassini. The data can last us for decades.

What is your educational background?

I obtained an undergraduate degree in physics and astronomy from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. I attended graduate school at the Planetary Sciences Department of the University of Arizona because of their big telescopes. I received a Ph.D. in planetary sciences that combines physics, astronomy and geology. I came to Goddard under their graduate student research program, obtained a post-doc and eventually became a civil servant. However, before my post-doc at Goddard, I had a brief post-doc at the Paris Observatory with Daniel Gautier, who is one of the founders of the Cassini-Huygens mission. Huygens is a probe built by Europe that hitched a ride on Cassini and landed on Titan in 2005.

What is your specialty?

The best way to describe my research over the past 30 years at Goddard is that I follow the water. My Ph.D. dissertation was studying water in Jupiter’s atmosphere. One source comes from inside the planet dating back to the planet’s formation. There is also an external source from comets and meteorites that burn up in the upper atmosphere.

The most famous example is when comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 burned up in Jupiter’s atmosphere in 1994. At the time, I was flying 41,000 feet over Australia using NASA’s Kuiper Airborne Observatory. It was fantastic! The plane also had some Australian and American teachers on board. The comet split up into 20 pieces. Some of the pieces hit Jupiter and nothing happened. I had flights for the two biggest pieces. We saw a spectacular fireball in which we detected water vapor. The Hubble Space Telescope photographed the impact sites.

How did you become interested in space?

As a child, I watched all the launches of Gemini and Apollo, from 1965 to 1972, on CBS TV with Walter Cronkite. I decided at age 9 that I wanted to work for NASA.

In addition to the space observations, what ground-based big telescopes do you use?

Large optical telescopes need to be located where it is high and dry. The main ground-based big telescopes I use are the Keck Telescope and the Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) both of which are on the summit of Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii.

How do these big telescopes operate?

At 6:30 a.m. this coming Sunday, I will be at Goddard at my desk using the IRTF to look at Jupiter. IRTF has a computer interface that allows me to see the same thing at my desk that the actual telescope in Hawaii is showing. In both cases, I see images of Jupiter on one side and spectra on the other side.

For the big telescopes, there is always at least one person at 14,000 feet, where the telescopes are located, who opens the dome, points the telescope and is responsible for their overall use and safety. The telescope operator moves the telescope to point at our objects, including planets and comparison stars for calibration.

I look at bright planets while others use the same telescopes to look near the edge of the universe. Only the big telescopes have high-resolution spectrometers, which split the light and allow us to key out the spectral fingerprint of water and other molecules. I need a dry night so that water on Jupiter is not overwhelmed by water in the Earth’s atmosphere.

How is the time on the big telescopes allocated?

Each big telescope has its own committee that allocates time among scientists. To request time, I write a proposal and submit it to the committee. It helps to request the same time as when the spacecraft is looking at the planet. The big telescopes’ observations increase the value of those from the spacecraft and help put them in context.

Who inspired you?

Virgil Kunde was the Principal Investigator for Cassini/CIRS, the Composite Infrared Spectrometer instrument on Cassini. My very first summer at Goddard, Virgil suggested to my thesis advisor that I spend the summer at Goddard which I did. And I kept coming back.

Virgil was involved in the Voyager missions of the 1980s. He got me interested in Voyager. The same people who designed the IRIS instrument on Voyager also built the CIRS instrument on Cassini. Both instruments were spectrometers. Goddard allowed me to combine ground-based and spacecraft observations.

Virgil was a great guy. He looked after his people. His subspecialty was the composition of the atmosphere, which is mine too. So we speak the same language.

Are you someone’s Virgil?

I was fortunate enough to work with Brigette Hesman, then a contractor at Goddard and now at Space Telescope Science Institute operations. We worked together over the last few years. We wrote papers and proposals together. I tried to let her know, as Virgil had let me know, that we are part of a team. We all get our hands dirty working with the data. We must be persistent. If we are lucky, we make a discovery.

In 2011, there was a big storm on Saturn. Brigette and I studied the storm and detected a large increase in hydrocarbons in the stratosphere, including ethylene, which was previously only seen in very small quantities. Brigette was the first author on the papers that came from this research.

How did an asteroid discovered in 1993 come to be named Brat Fest?

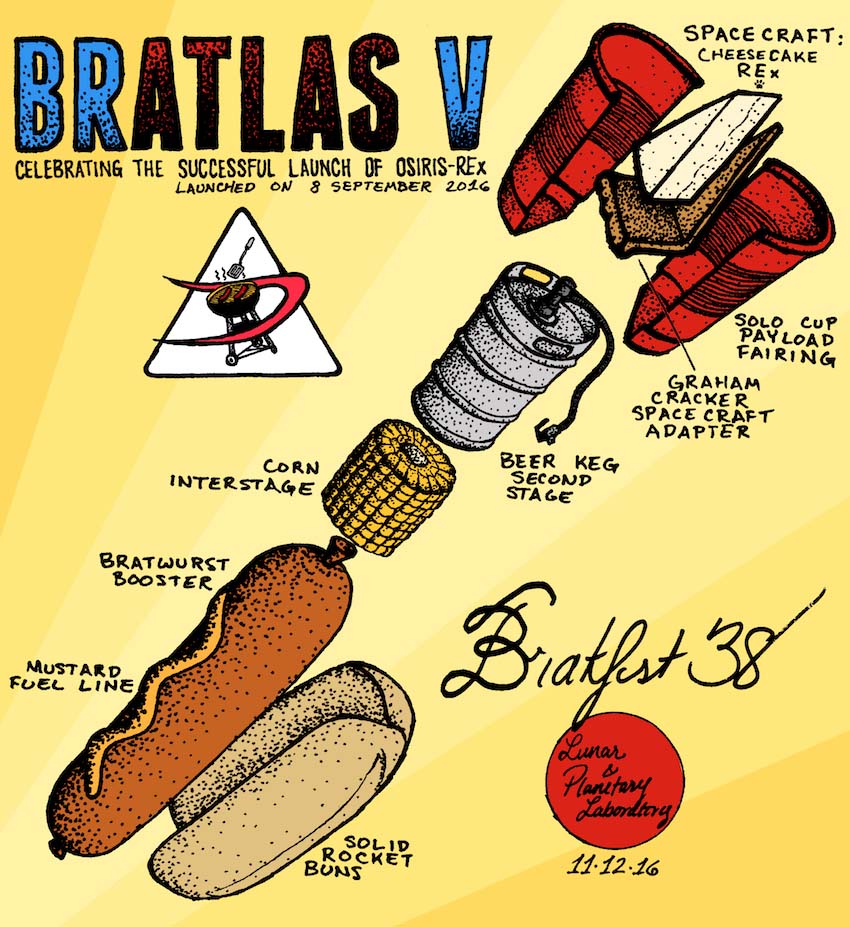

I was one of three co-founders of Brat Fest, a big party founded in 1979 by University of Arizona in Tucson graduate students originally from Wisconsin. We are approaching immortality with BF 38 last fall.

Each Brat Fest has beer, bratwurst, corn and cheesecake in a tribute to the corn festivals of Wisconsin. The cheesecake was our added touch.

Every year we have a different link to a spacecraft and make an appropriate T-shirt. In the 1980s when Voyager was flying, our T-shirts featured “Forager.” To celebrate the successful launch of the Origins-Spectral Interpretation-Resource Identification-Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-Rex), Brat Fest 38 had a very special poster and T-shirt.

My favorite poster was for Halley’s Comet in 1986. In 1066, Halley’s Comet was observed across Europe and was not viewed as a good omen. In fact, in medieval times, seeing a comet meant someone would die. Shortly after, the French made the Bayeux Tapestry that includes the Latin phrase “We marvel at the star.” In a tribute to the Bayeux Tapestry, our Brat Fest T-shirt featured “We marvel at the brat.”

The closet Brat Fest is held at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab in Maryland. The original continues to this day at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Since the other two co-founders are now in Colorado, the University of Colorado, Boulder, also continues the tradition. We have even had one in Australia.

Is there something surprising about your hobbies that people do not generally know?

I ride and photograph trains. My favorite train is “The Canadian” which goes from Toronto to Vancouver through the Canadian Rockies. When I have meetings in Europe, I ride their high-speed trains. There is some remote connection to my work as steam locomotives are powered by water vapor and I study water vapor. But I just like trains.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.