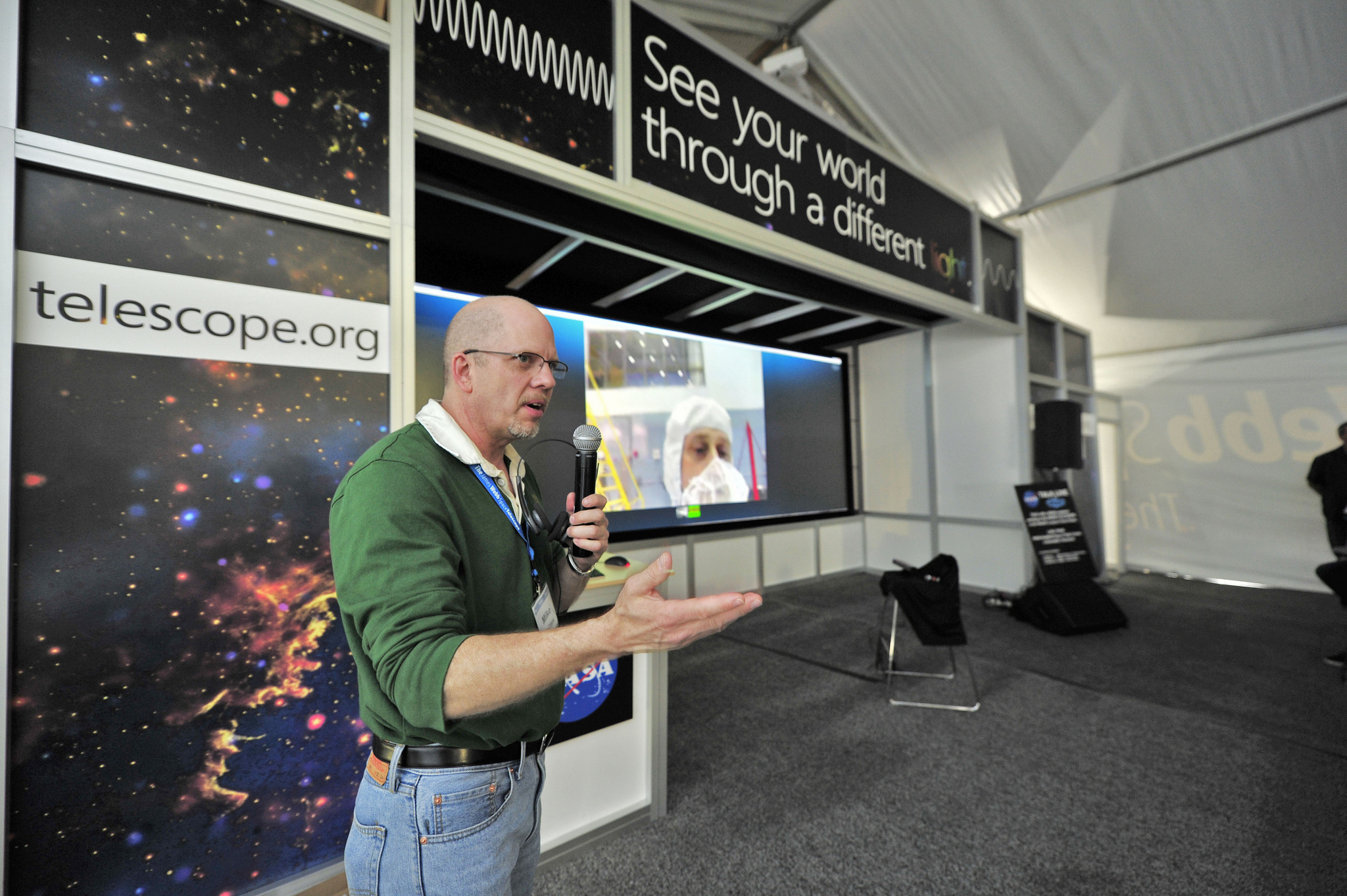

Name: Mike McClare

Title: Principal Media Producer for the Webb Telescope

Organization: Code 731, in support of Code 130 – Office of Communications

Mike McClare is Webb’s creative storyteller who employs his engineering brain to map out his tales.

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

As lead producer for media for the James Webb Space Telescope, I produce and direct media productions supporting the Webb telescope mission, which includes script writing, coordinating the production logistics, videography, editing, creating motion graphics and working with digital artists to develop animations. I work with a small team of very talented people who help tell the stories and science of Webb to the public.

I make sure that the production is completed on time, correctly and on budget and to the satisfaction of my customer, in this case, the Webb telescope mission management and outreach team.

What specialized tools do you use?

I use a wide variety of cameras including high-definition cameras, 4K cameras (4K is a new high quality video format) and 3-D camera systems. I use whatever camera suits the purpose based on the project, the situation and availability. I don’t have a favorite brand.

How do you view yourself?

I’m a creative storyteller with an engineering brain.

What does creative storytelling mean to you?

I liken it to using a variety of media “brushes and paints” to create a “picture.” I mix script writing, videography, animation, graphics, music and a variety of other tools to tell a story or relay a science concept in an impactful way.

Before I can do any of that, I need understand any science or engineering involved

so I can boil that down for the general public to understand. Sometimes the most difficult and time-consuming part of the process is determining the most effective way to communicate a concept in a very short period of time to a generally non-scientific public.

That doesn’t mean coming up with some crazy creative concept just to be creative, it means knowing your audience. It means knowing your budget and your deadline. It means producing a video that tells the story in a fun, easy to understand way.

For example, a lot of people ask why the Webb telescope is so large. The primary mirror is 6.5 meters (21 feet) in diameter. The primary mirror needs to be at least this large to collect enough light to image the most distant objects in the universe. So, we explain this concept using an analogy to rain gauges collecting water. After an inch of rain has fallen, a very wide container will collect much more water than a thin tube. Both collectors will show only an inch of rain has fallen, yet the wider collector will have much more water which is analogous to Webb’s great observing power.

What we do here is really cool. I try to capture the “amazing” factor in the storytelling work we do here. My biggest worry is becoming jaded and losing that childlike curiosity.

How does having an engineering brain help?

Telling stories about what’s going on with the Webb telescope present challenges that require me to be more of an engineer. I am not an engineer by training, but I think like an engineer.

For example, the Webb telescope is being built in our largest clean room. The clean room has a specially built structure used to assemble the telescope. The structure blocks the view for tours to see work being done on the far side of the clean room. I designed and installed a remote-controlled camera inside the clean room so that our visitors can see what is happening on the other side of the structure.

I also spent about a year of trial and error trying to find a material and ink acceptable for long-term use in the clean room. Once approved, we used the material and ink to make the 10-foot-by-30-foot NASA and Goddard logo banner displayed inside the clean room.

Please tell us about the time lapse of Webb that you and photographer Chris Gunn have been collaborating on for the past five years?

The time-lapse project is a marriage of video and photography. I’m mainly involved with the video and Chris is doing the photography. I’ve worked side by side with Chris on this project for five years and on Hubble before that.

This time-lapse project documents the incredible story of building the Webb telescope. We’re using time lapse to show how everything comes together. Our goal is to capture the process from the very beginning all the way through launch. We’re creating a full-length, narrated production telling the story of building the Webb.

The time-lapse project has four dedicated cameras. Two are always on and will remain in the same position for five years. Each of these cameras takes a picture every two minutes. We place the other two cameras in locations to get more dynamic views of assembly activities as needed.

When finished, the time-lapse images will play at 30 frames per second, meaning 30 individual photos will appear every second of the movie. A time-lapse movie one minute long has about 1,800 individual frames.

We’ve collected almost a million frames already and we have two-and-a-half more years to go. We store the frames on a hard drive and also on a secure network server.

We recently released a taste of the feature focusing on the primary mirror assembly. We condensed 83 days resulting in 160,000 images into a one-minute video.

What is the most difficult part of your job?

We have to work within the restrictions of International Trafficking and Arms Regulations that protect certain technology. Our ITAR lead approves all of our visuals before we release them for public use. To comply with ITAR, we can’t always do close-ups. We have to choose angles so as not to expose protected technology. My team needs to have a pretty good handle on what technology is ITAR-sensitive so that I don’t waste time shooting it.

How do you overcome some of the challenges of shooting in the clean room?

Shooting in the clean room can be a challenge, but I can overcome that challenge by being prepared. We have to go into the clean room with everything that we will need for the shoot. The Contamination Control team cleans all of our equipment before it can be used in the clean room. That process can take up to an hour or more depending on their workload and the amount of gear we intend to bring in. The Contamination Control staff use swabs dipped in isopropyl alcohol, high pressure air and other methods to physically clean all of the surfaces of every piece of equipment.

Humans are the dirtiest objects in a clean room. Our skin and hair shed and can create dust particles, so we humans have to go through an air shower and gown up in special clothing that covers us head-to-toe, affectionately called a bunny suit. Gowning takes about five minutes. No one wants to bring dust into the clean room.

Going into the clean room feels like entering a special world. The air is always gently blowing because the filters are continuously cleaning the air. The temperature is about 68 F. There is a constant background fan noise. You get the occasional loud buzzer sound when the crane is about to start moving. You recognize co-workers by their eyes, height and sometimes by the way they walk.

I try to make a point of soaking in the environment, what’s happening and the uniqueness of the opportunity to be in there with the spacecraft. This opportunity won’t last forever.

Why did you become a producer?

When I was in middle school, my friends and I formed an 8mm film club. I had a little film editing system at home. We made alien movies, mystery movies, sports films, documentaries and silly stuff. It was a fun hobby.

My real passion was music, with a goal to becoming a rock star. I played guitar and looked the part with natural curly hair just like Peter Frampton. Peter Frampton and I continue to share the same hairstyle today.

My mother always supported my music but strongly suggested I should find something to fall back on if being a rock star didn’t pan out. Media production is a career that constantly pushes my creativity, challenges me technically, and offers a vast plate of experiences through travel and meeting people. It allows me to incorporate my musical side. It’s the perfect back-up plan. And since my dreams of rock stardom haven’t panned out yet, I’m thankful everyday for the truly amazing career I fell back on.

What is your educational background?

I have a bachelor’s in mass communications and psychology from State University of New York College at Brockport.

What did you do after graduating?

I taught television production for three years at the innovative Webster High School in Webster, New York, before coming to Goddard. I enjoyed teaching the students how to use the television medium to tell compelling stories. I got tenured after three years and then took a year off to work in the “real-world” for a bit.

Where did you do after teaching?

I worked with a Rochester, New York, production company. We produced an hour-long children’s film called “Doug and Garry, the Happy Pirates.” The film won a Parents’ Choice Award in 1990. I was having a lot of fun, and there were lots more opportunities in the pipeline, so I decided not to go back to teaching. It lasted a year then, the bottom fell out of the market during the recession, and the business laid off everyone.

How did you get to NASA?

After being laid off, I set my employment sights on the FBI or NASA. I kept just calling.

Finally, NASA Headquarters had an opening. I talked them into giving me an interview. They said I was so far out of town that it probably wasn’t worth me coming in for an interview. I talked them into it anyway. I drove down from Rochester and stayed in D.C. at my own expense, had a great interview and got the job.

NASA said that the key reason they hired me is because I went above and beyond – I showed drive and tenacity. My production skills were pretty good too. I try to instill that drive in my own kids.

Have you also freelanced?

In 2010, I was the lead videographer for PBS’ Nova special called “Hubble’s Amazing Rescue,” which was broadcasted nationally. I’ve also worked with the Discovery Channel on their national show called “Alien Worlds,” where I got to film astronaut Buzz Aldrin. Recently, I helped Doug Leviton, a Webb telescope engineer and optics genius along with his wife Marianne, make the documentary called “Line in the Sand,” about Matador, Texas, a small town, struggling to survive.

It’s always fun to get outside the NASA bubble, meet other people and do other projects.

What qualities have made you successful?

I think that my mindset, passion and drive got me to where I am today. I will do whatever it takes to accomplish my goals. It might take a while, I may hit a million brick walls, but I’ve rarely failed. I’ve learned that if you hit a roadblock, there’s always another approach. I’m incredibly driven. I pride myself on doing top-notch work.

What makes a good producer?

Be observant. Understand your audience. Understand your customer. Be prepared. And whenever possible give your audience “sparklers,” little nuggets, that make them think or, simply go “wow.”

I’m on the Webb Team. My job is not only to telling Webb stories, but to make everyone on our team look good and sound good. I want my customer to be happy with what I’ve produced for them.

What about your aspirations to be a rock star?

Unfortunately, I’m still not a rock star, but I get to rock-out playing guitar, a little keyboard and singing with a band called Benfield Rush. We got our name from the main road in Severna Park, MD where most of the original members live. We’ve been playing together for about five years at local clubs. We perform music from the 70’s through today. My NASA Goddard officemate, Mike Velle is also in the band.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.