In 1967, the United States and the Soviet Union were very much in a race to be first to land a human on the Moon. The Soviet human lunar program received formal government approval in 1964, and one of the key components of that program was the rocket called the N1, comparable in size to the American Saturn 5 Moon rocket. These tests had significant impacts on key Apollo Program decisions.

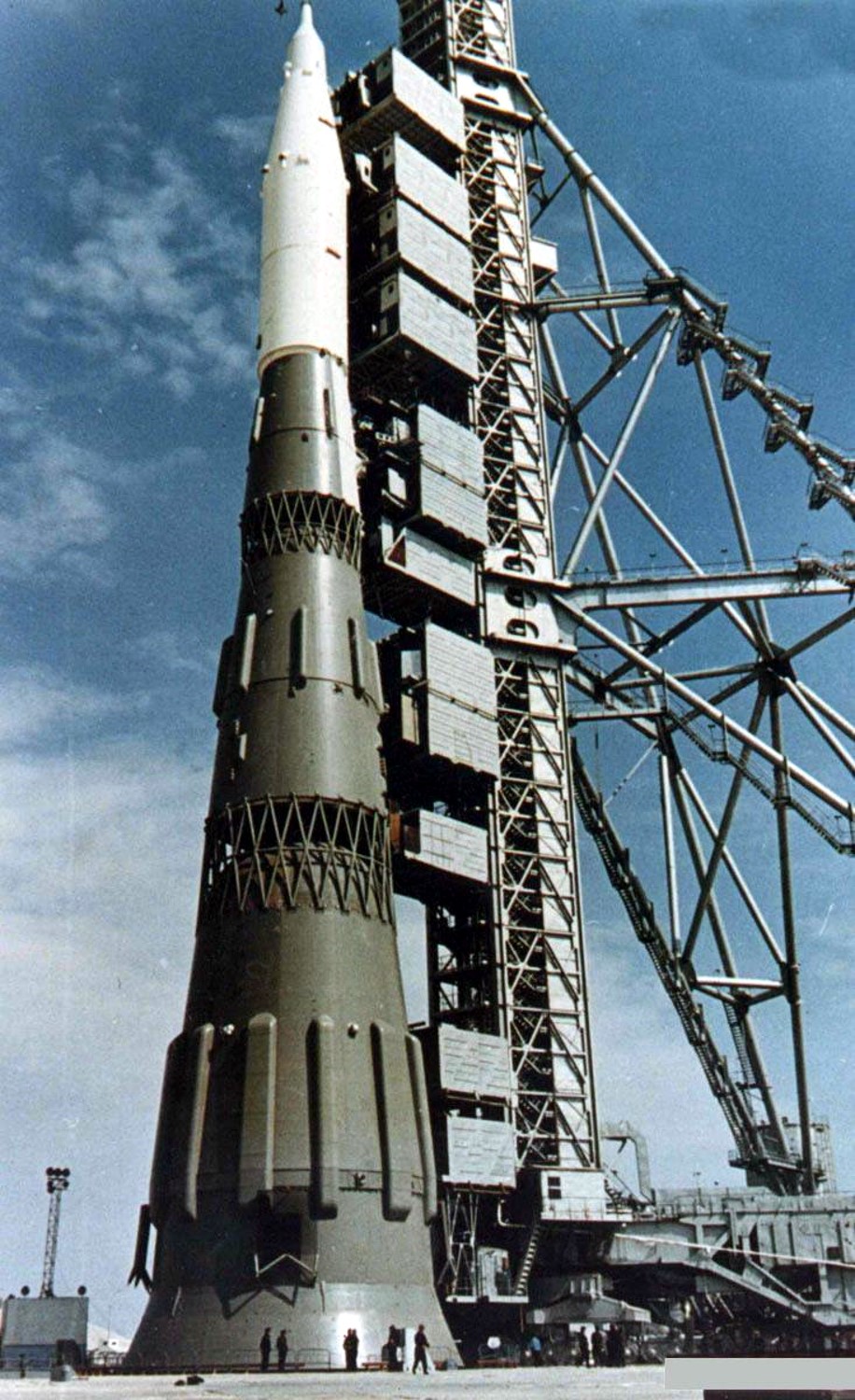

On Nov. 25, 1967, less than three weeks after the first Saturn 5 flight during the Apollo 4 mission, the Soviets rolled out an N1 rocket to the newly constructed launch pad 110R at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Soviet Kazakhstan. This particular rocket, designated 1M1 and also called the Facilities Systems Logistic Test and Training Vehicle, was actually a mockup and designed to give engineers valuable experience in the rollout, launch pad integration and rollback activities, reminiscent of similar tests conducted with a mockup Saturn 5 at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in mid-1966. While the crawler transported the Saturn 5 to the pad vertically, the N1 made the trip horizontally and was then raised to the vertical at the pad – a standard practice in the Soviet space program. On Dec. 11, after completion of various tests, the N1 rocket was lowered and rolled back to the assembly building. The 1M1 mockup would be used repeatedly in the coming years for additional launch pad integration tests.

Although this test was carried out in secret, a U.S. reconnaissance satellite photographed the N1 on the pad shortly before its rollback to the assembly building. NASA Administrator James Webb had access to this and other similar intelligence that showed that the Russians were seriously planning manned lunar missions. That knowledge influenced several key U.S. decisions in the coming months. The satellite imagery appeared to show the Soviets were close to a flight test of the N1, but could not reveal whether this particular rocket was just a mockup and that the Soviets were many months behind the U.S. in the race to land a human on the Moon. At this time, the Soviets were hopeful that they could carry out a test flight of the N1 in the first half of 1968, but for a variety of technical reasons the attempt would not occur for more than a year.

For more on the influence of the Soviet program on Apollo decisions, see http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2962/1