Part Two of Two

Name: Pamela Conrad

Title: Deputy Principal Investigator for Sample Analysis at Mars and Scientific Co-Investigator and Instrument Scientist for the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument suite.

Formal Job Classification: Research space scientist

Organization: Code 699, Planetary Environments Laboratory, Science and Exploration Directorate

Scientist Pamela Conrad helps give Curiosity a daily to-do list to look for life’s building blocks on Mars.

What is your involvement with the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument suite?

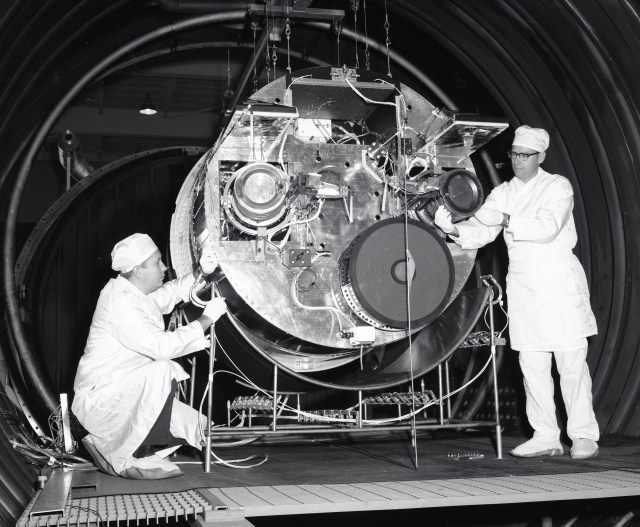

SAM is the most complicated science instrument ever sent to another planet, in this case, Mars. SAM is in the belly of Curiosity, the Mars rover. SAM measures the chemistry of gases. Sam can breathe in air. If what we want to measure isn’t a gas, SAM can bake rocks in one of two ovens until they become a gas and then measure it. Light chemicals are driven off upon heating, which is why your food smells when heated. That’s how we measure gases on Mars.

There is a history of baking rocks on Mars. Viking did this in the mid-1970s. But Curiosity is the first MARS rover that can drill inside rock and deliver it to analytical instruments. We couldn’t bring home the bacon, but we could certainly fry it in the pan.

I have a couple of roles. For our team in specific, I’m in charge of operations. The science I work on has to do with understanding the isotopes of the inert gases krypton and xenon that SAM measures in the atmosphere of Mars. For the broader mission, I rotate through leading the science operations working group a few days a month. This is the group that tactically decides what to do on Mars for that day and it generates plans to send to rover to execute that science. We have a strict time limitation caused by the position of Earth and Mars, so we only have a small period of time every day within which to send instructions. We give Curiosity a to-do list every day, and every day we also receive back data based on that list.

How do you communicate new discoveries from Curiosity?

We try to be as transparent as possible and use words that are understandable to those who don’t have a specialized education. We are accountable to every single citizen as taxpayers. We are also accountable to the entire world because we build on discoveries. Someone will take what we learn and use that information to build the next thing. This is how we evolve our science and technology.

What do you think will be Curiosity’s legacy?

Curiosity rover is bringing back information about the chemistry, physics, weather, geology and mineralogy of Mars, our nearest planetary neighbor. This information helps us understand a broader picture of the processes that have affected Mars. In understanding those processes, we hope to understand how common it is that a planet can evolve into conditions that can support life.

Curiosity also offers a lesson in what a good, very large team based all over the world can do when working cooperatively towards a common goal. On any given day, we have many, many people working as a team. The composition changes daily. No one person can work this intensively every day. We have team members from all over the world and we rotate in and out nearly seamlessly. Every single day, for two years, this humongous team has worked very well together to send instructions to a robot millions of miles away. I am proud to be a part of it.

Were you involved in fieldwork?

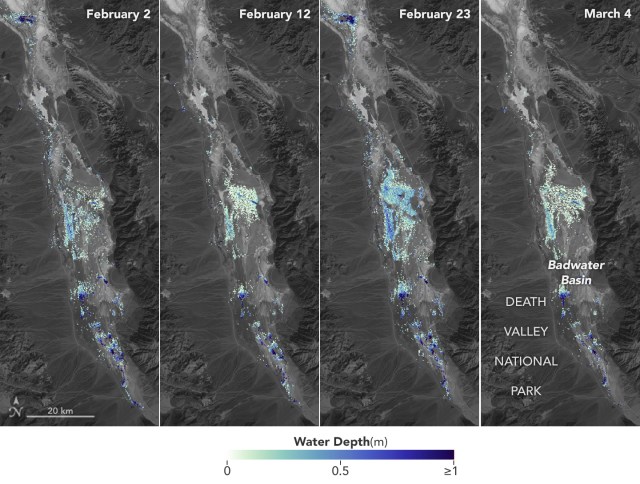

Yes, in order to understand the environments of other planets, I spent about 13 years exploring extreme environments on this planet. I’ve been to the Arctic, the Antarctic, the very bottom of the Pacific Ocean, Death Valley and lots of alpine deserts. One must prepare for robotic exploration by first exploring in the flesh so that the approach can be defined and we can tell the rover what measurements are needed.

Why did you become a scientist?

I initially was a singer and composer. I had a media production company that produced videos about medical education and science. One day I was on a shoot and it was raining, so I cut through the geology building on the campus of George Washington University to keep the equipment dry. We walked right by a giant showcase of beautiful minerals and crystals. Looking at those rocks, I made the decision right there to go to school to become a scientist. I thought that I would have more fun doing science than making videos about someone else doing science.

School took me 12 years. My undergraduate degree was in music, so I had to go back for all the science credits. I now have a doctorate in mineral physics, a specialty of geology.

Why are public engagement activities so important?

I am also involved with a lot of public engagement activities. Working with students and the public is an important responsibility. Everyone who has the good fortune to be doing something as amazing and fun as space exploration should take seriously our relationship with the public. We get to work at one of the coolest places on this world and virtually off of it. It’s important to recognize that we have something very cool to share with the citizens who pay for it.

When I was 14, I received a medal as an award for a science fair from NASA at a ceremony at Goddard. The medal is the size of a coin and engraved with my name. I take this medal with me whenever I go somewhere especially challenging. It was in my pocket when I went to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

My point is that education and public outreach efforts are important. They pay off later. Here I am – on Mars.

In your past life, what kind of singing did you do?

I was an opera singer. I trained locally and also in New York with Sebastian Engelberg, who was a very well-known singer and teacher at Mannes Conservatory. My favorite role was Cherubino from Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro.” It’s a very comical role. I also sing other styles of music including rock, jazz and acoustic. Right now I mostly sing in the car; I’m pretty busy with Mars!

Read Part One of Pamela Conrad’s interview

Read more Conversations With Goddard

Also read about what our people do Outside Goddard