Nuclear Thermal Propulsion technologies are the subject of a new test series at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Researchers there are using an innovative test facility to study the properties of highly promising nuclear fuels — without the risk of radiation exposure associated with handling these potent power sources. The current test series focused on analysis of a variety of fuel elements in a simulated thermal environment kicked off in early October with completion targeted in June 2015.

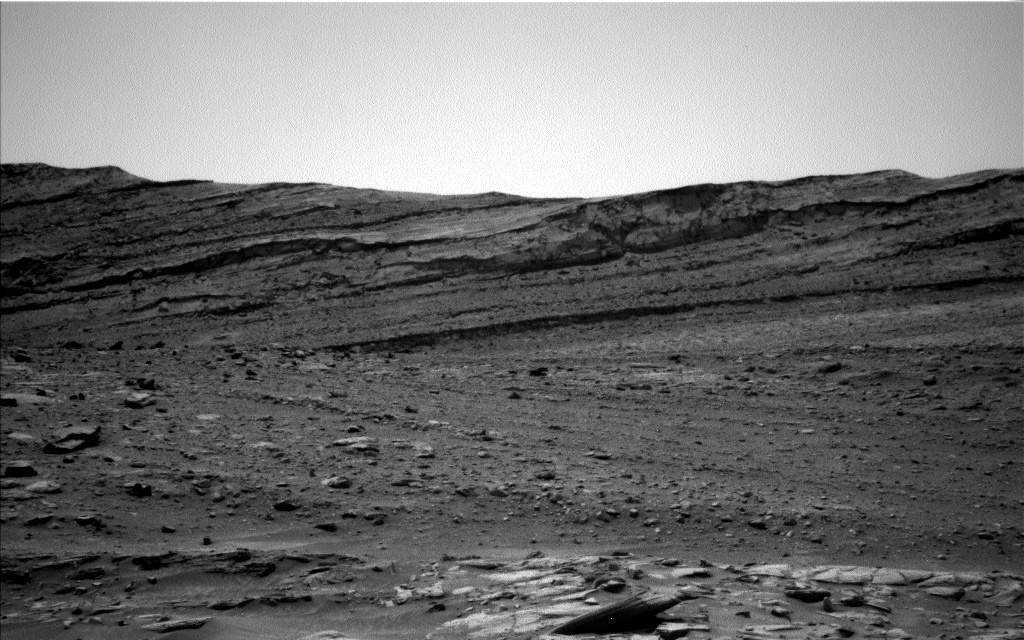

Michael Houts, NTP manager at the Marshall Center, said the safety factor is good news for scientists and technologists developing the technology — and the advances enabled by the study will yield even better news for flight engineers and NASA mission planners. Nuclear thermal rockets “may be ideal to enable delivery of very large, automated cargo payloads to Mars, paving the way for human explorers,” he said.

The same nuclear thermal propulsion technology, reconfigured for speed rather than mass, then could potentially transport human crews to the Red Planet as well, which would get them there more quickly and efficiently than conventional rockets while reducing astronauts’ solar radiation exposure during the voyage.

In short, Houts said, “Nuclear thermal propulsion could be the ticket to Mars. The results from this study will give us a better idea of whether that is the case by experimentally measuring key factors related to engine performance and lifetime.”

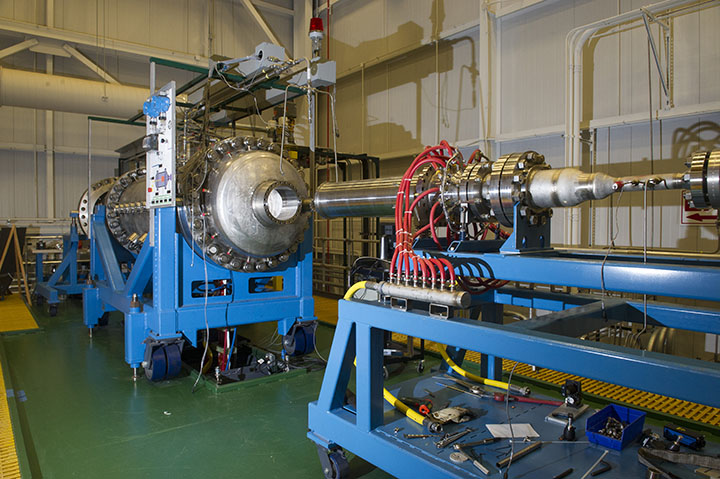

Housed in the Marshall Center’s Propulsion Research and Development Laboratory, the test facility used for these innovative studies is dubbed “NTREES,” short for the Nuclear Thermal Rocket Element Environmental Simulator. Licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the facility is certified to test prototypical nuclear rocket fuel elements. These are identical to the fuel elements used in a nuclear thermal rocket, but because the test facility uses non-nuclear heating instead of nuclear fission, the fuel does not become radioactive during the test and can be easily handled and examined once the test is complete.

NTREES safely tests these stand-in, prototypical fuel elements in hot flowing hydrogen at power levels and temperatures comparable to those found in a working nuclear thermal rocket engine. Induction heating is used to mimic the fission process, with pressures reaching 1,000 pounds per square inch and temperatures approaching 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

“The cost savings is remarkable,” said Marshall researcher Bill Emrich, who manages the NTREES facility at Marshall. “Whereas it costs tens of millions of dollars to perform full-scale testing of nuclear rocket fuel elements in specially designed nuclear reactors, our research costs just tens of thousands — and no radiation protection is required!”

Houts concurred. “By using this non-nuclear induction heating process for testing, we avoid the environmental, legal and security issues associated with performing full-powered nuclear tests — and advance this research far more quickly than we could do otherwise,” he said. “And when, in time, we conduct actual nuclear testing, we will have very high confidence that those tests will be successful, thanks to these initial, non-nuclear studies.”

The focus on safety extends beyond the laboratory to the launch pad, Houts noted. A chemically powered launch vehicle, such as NASA’s next flagship, the Space Launch System, could safely carry a nuclear-thermal-powered upper stage to orbit. During ascent to orbit, the nuclear system would remain “cold,” with no fission products generated and radiation below significant levels.

Once safe orbit was achieved, the upper stage would deploy, and its nuclear reactor would be activated, heating hydrogen to extremely high temperatures. The hydrogen then would expand through a nozzle, generating thrust.

Such an engine is expected to operate twice as efficiently as a standard chemical engine, Houts said. The Space Shuttle Main Engine, which powered space shuttle missions to Earth orbit for 30 years and is generally considered one of the best, most efficient chemical engines ever built, delivered a specific impulse (ISP) of 450 seconds. A nuclear thermal rocket, in comparison, would deliver an ISP of 900 seconds. That dramatic increase in efficiency could enable reliable delivery of high-mass automated payloads into the deep solar system, or help high-velocity, human-rated vehicles speed to and from Mars and other destinations in as little as half the time required by today’s rockets.

Right now, though, NTREES research is driven by one critical goal: enabling a human mission to Mars. The current round of testing lays the groundwork for large-scale ground tests and eventual full-scale testing in flight.

After that? “Mars, here we come,” Houts said.

Nuclear thermal research at the Marshall Center is part of NASA’s Advanced Exploration Systems (AES) Division, managed by the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate and including participation by the U.S. Department of Energy. AES focuses on crew safety and mission operations in deep space, seeks to pioneer new approaches for rapidly developing prototype systems, demonstrating key capabilities and validating operational concepts for future vehicle development and human missions beyond Earth orbit.

Marshall researchers are partnering on the research with NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio; NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston; NASA’s Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi; Idaho National Laboratory in Idaho Falls; Los Alamos National Laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

For more information about NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, visit: