Future aircraft may be equipped with radar capable of warning of a certain type of potentially hazardous icing conditions at high altitude thanks to research just completed by NASA’s aeronautical innovators in Florida.

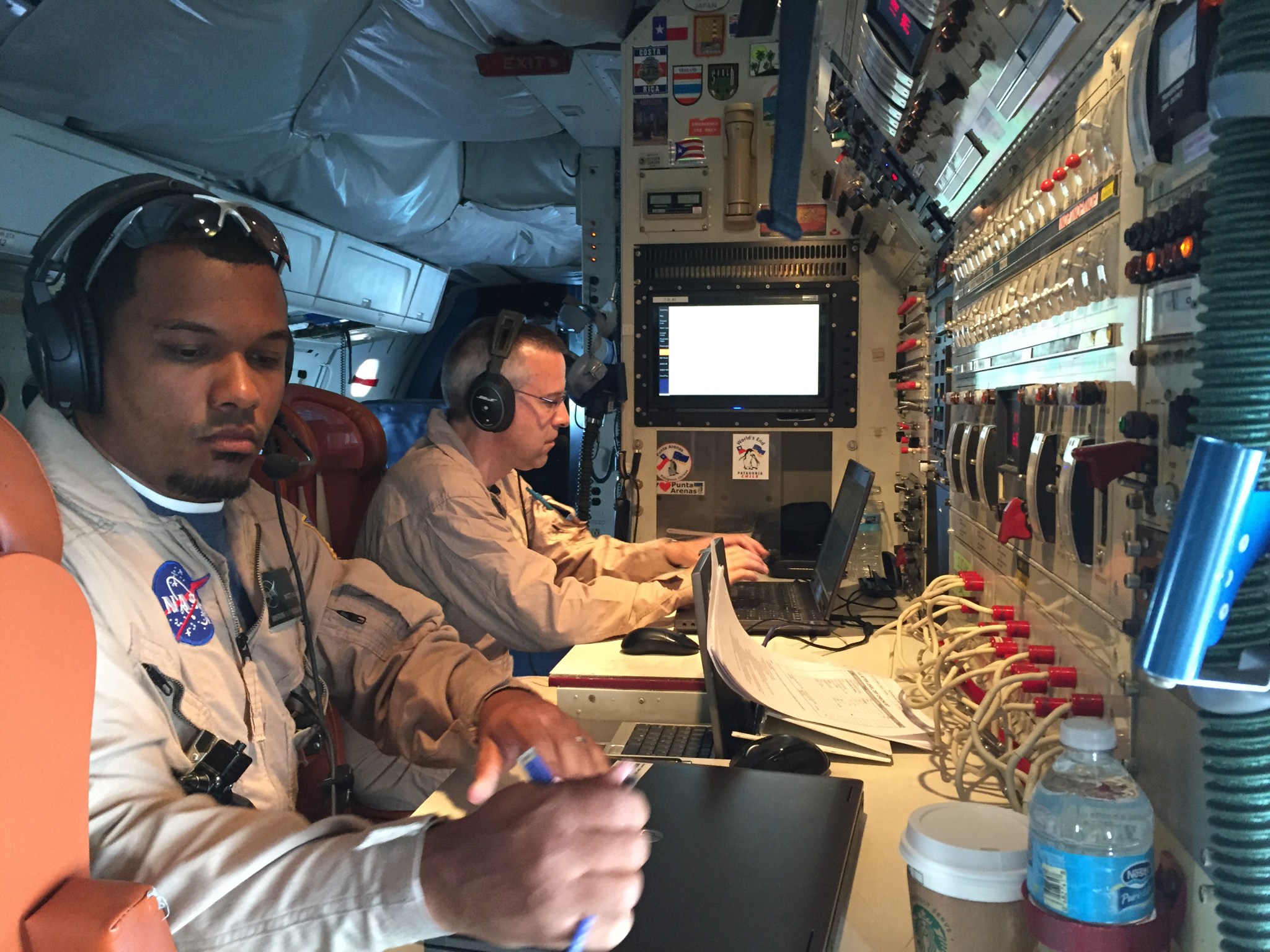

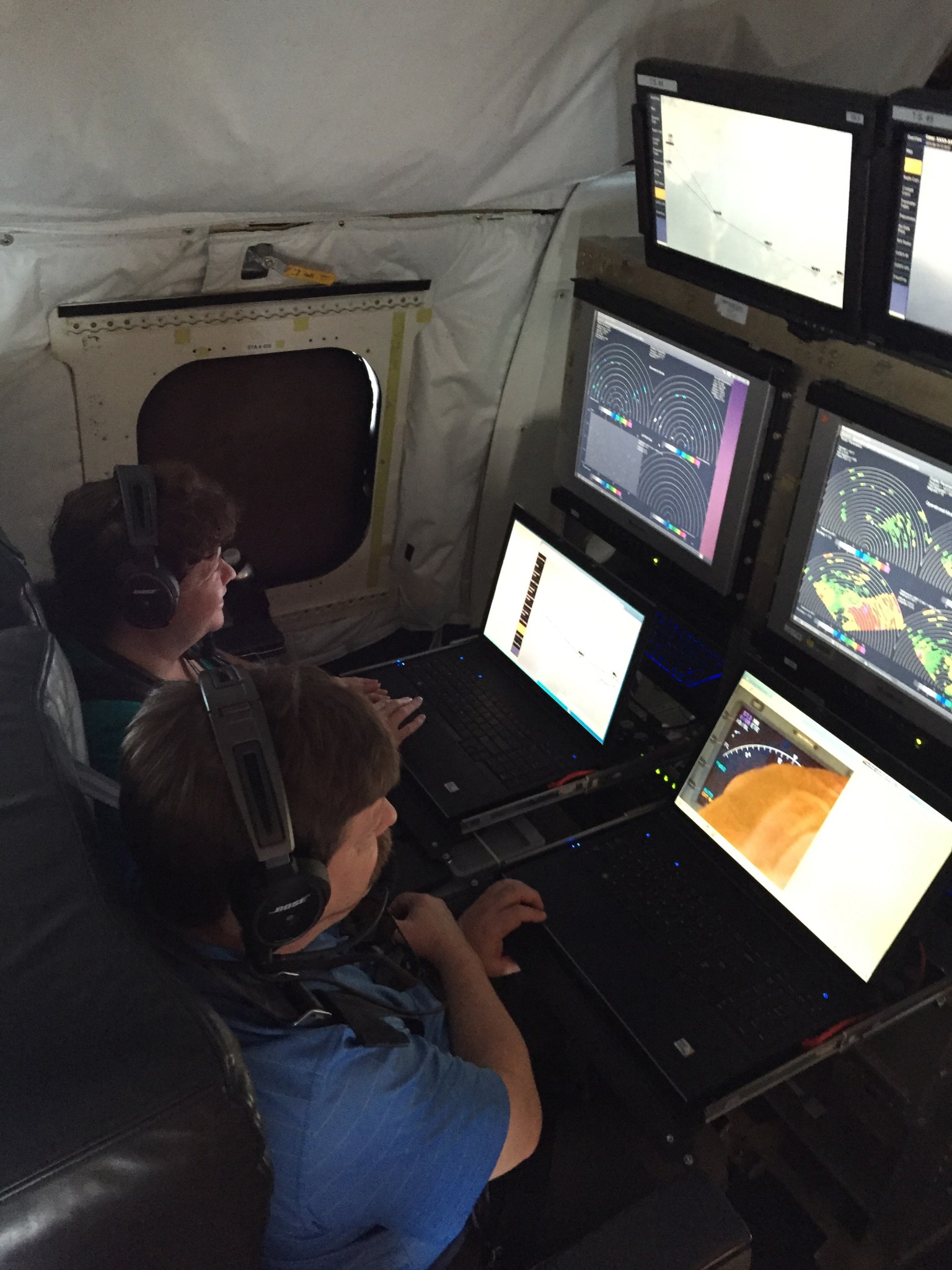

With a baker’s dozen of science instruments and off-the-shelf weather radar, a combined government-industry team flew NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center’s DC-8 research aircraft in and around bad weather, including two tropical storms, in search of conditions that produce ice crystal icing conditions at high altitude.

The campaign, which ran from Aug. 10-30, collected almost 72 hours of in-flight meteorological and radar data associated with adverse weather and thunderstorms.

“Tremendous doesn’t even begin to capture how well everything went. We exceeded expectations in every way we could,” said Steve Harrah, principal investigator of the High Ice Water Content (HIWC) project at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

Current weather radar can detect rain or hail, but is limited in its ability to discern which types and smaller sizes of ice crystals are in the atmosphere, which can lead to pilots encountering some challenging flying conditions.

When ice crystals hit warm aircraft engines, they start to melt and evaporate, cooling the engine core surfaces to temperatures below freezing. The cooling engine causes the melted ice crystal water to refreeze, and ice accumulates inside the engine core. Ice in this location may cause temporary power loss or engine blade damage.

Previous research campaigns with industry and other government agencies in Australia and South America were successful in characterizing the weather conditions that can lead to ice crystal icing conditions – generically referred to as HIWC.

The goal for this NASA-led research campaign, which also involved the FAA, The Boeing Company, and other industry partners, was to record both instrumented weather and standard radar data as the plane flew in known HIWC conditions, and then see if by comparing the data a potential HIWC radar signature could be identified.

“We wouldn’t expect to be able to measure or actually detect HIWC conditions. That would be an exaggeration,” Harrah said. “But what we do think we can do now is come up with a signature and some type of display that would tell pilots there is a strong likelihood of HIWC conditions in a certain location.”

With that information pilots could take steps to avoid any problem, either by altering course or by engaging some still-to-be-developed device or procedure with the engines themselves that would protect the jets from icing conditions.

A dual band weather radar would be able to better measure ice concentrations, but replacing today’s single band weather radar used on airliners around the world would be costly.

“So we’re trying to find a low cost, software-based solution that could be applied to many radars and many airplanes across an airline’s entire fleet,” Harrah said.

Meanwhile, the HIWC flight campaign experienced several research firsts, including seeing conditions in which a total air temperature probe indication changes from well below freezing to freezing, and the airplane’s pitot tube fails – both of which result in giving pilots false readings about their airspeed,

“In many of our flights, we experienced events that have occurred on other commercial aircraft. The difference is that with our full suite of instruments, we were able to record the conditions that caused those things to happen. By understanding the conditions that cause these events, we can help improve flight safety in the future,” said Tom Ratvasky, a co-investigator with NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland.

The flight campaign also marked the first time in research history that an airplane equipped with both an ice water measurement suite and pilot weather radar recorded conditions associated with tropical storms, in this case Danny and Erika.